The early 1970s was the era of Soul Train on television and the rise of the Blaxploitation movement in the movie theatre, as well as the time of Ike & Tina Turner, Billy Preston, and Diana Ross, and a ton more. Marvel Comics, having supplanted the older DC as the most popular game in comic-book town, was trying to stay on top. With the rise of Blaxploitation, they decided to capitalize by providing a superhero who was in the same mold as Shaft and Sweetback and Super Fly and Cleopatra Jones.

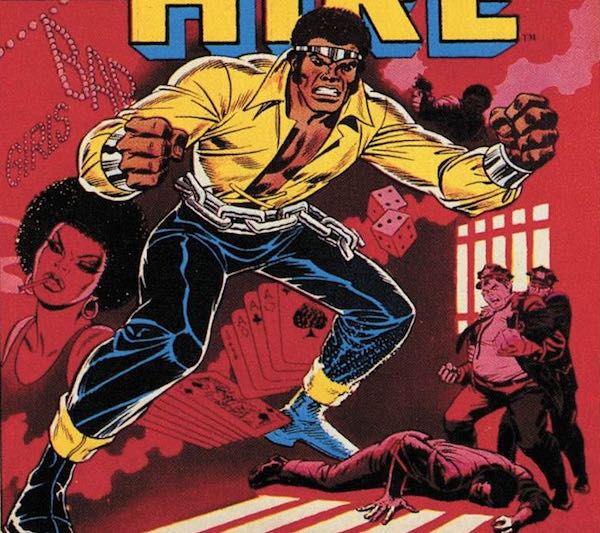

And so Luke Cage, Hero for Hire debuted, the first ever comic book series to solely star a black character. Written by Archie Goodwin and drawn by George Tuska (both white guys), it showed a side of New York rarely seen in the grand battles of the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, or even the street-level adventures of Spider-Man and Daredevil (this was before Frank Miller took DD to darker places). Cage’s New York was the grimy streets of Times Square, before Disney got its mitts on the place—home of prostitution and drugs and thievery and gangs, the New York that suffered a major fiscal crisis and high crime rates, the New York that was refused federal aid by President Gerald Ford, prompting the famous headline “FORD TO NEW YORK: DROP DEAD.”

It was that New York, the New York of the 1970s, that birthed Luke Cage.

Several things made Cage stand out from the other heroes, besides the color of his skin and his base of operations. For one thing, his name didn’t have “black” in it, which was a very tiresome trend: Black Panther, Black Goliath, Black Lightning over at the other company. Eventually, Cage took on a codename, but it was the delightfully generic “Power Man.” (In fact, there have been three Power Men in Marvel history—one white, Erik Josten, these days known as Atlas; one black, Cage; and one Latino, Victor Alvarez, who still uses the name.)

And for another, he charged for his services. It’s one of those things where you wonder why nobody thought of it sooner (and why you don’t see it more often). Spider-Man’s money problems would be a thing of the past if he got paid for his hero work, after all. Of course, there are ethical issues to consider, not to mention the whole issue of great power and great responsibility—but also sometimes people need to know they have a hero on the payroll.

Over the years, Cage’s appeal was the same as that of most of Marvel’s heroes: he was, at heart, a regular guy. A completely different type of regular guy from, say, Peter Parker, but the black community deserved their own workaday hero who kept an eye on the little people. And sure, a lot of his dialogue from the 1970s will make a modern reader wince like crazy (overuse of words like “baby” and “jive” and such), and yes, he wore a tiara and a yellow shirt and a chain around his waist.

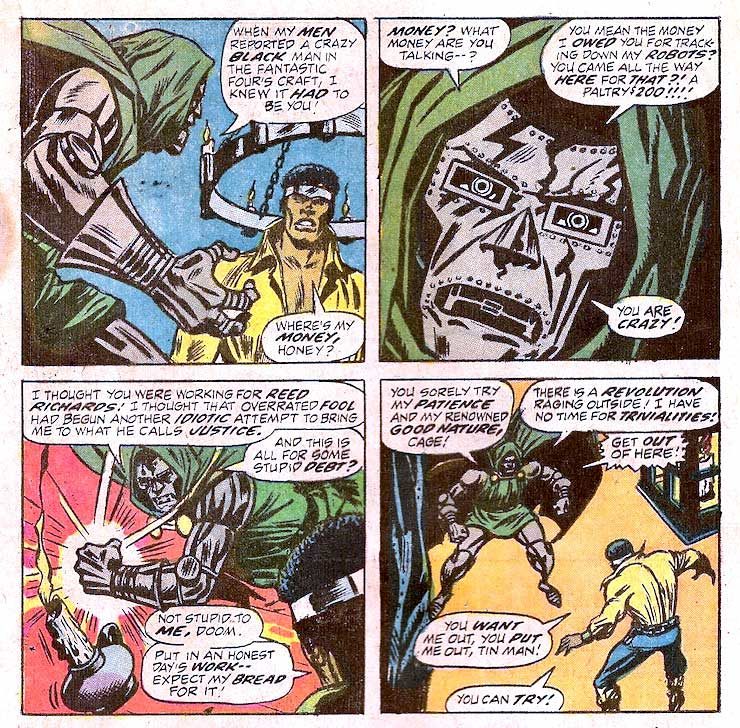

But Cage was still the coolest cat on the block. This is a guy who flew to Latveria to beat the shit out of Doctor Doom because the armored villain reneged on his fee. This is a guy who, when asked where his partner Iron Fist was, said, “Meditatin’. That’s like suckin’ your toes only not as much fun.” This is a guy who, when informed of all the things that can kill a vampire (crosses, garlic, etc.) when he suddenly finds himself facing one, grumbles, “Brilliant, D.W., you know I never set foot outside my house without a pocket full’a them things!”

Cage has always been a loner. His best friend betrayed him and framed him for possession, sending him to Seagate Penitentiary, where he was the target of racist corrections officers. Subjected to an experiment of a type that is part of far too many comics origins—an experiment sabotaged by the racist CO—he gets super-strong skin and super-strength, and uses them to break out of prison. Changing his name from Carl Lucas to Luke Cage, he goes to New York, gets revenge on the man who betrayed him, and eventually even manages to clear his name.

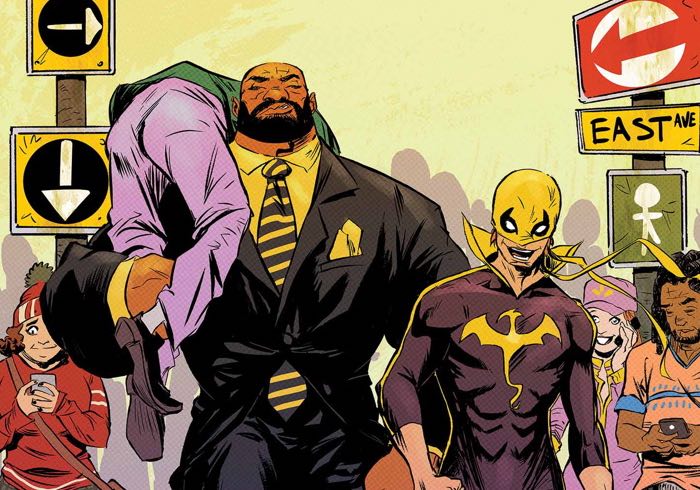

And yet, Cage has always had support: from Noah Burstein, the scientist who gave him his powers, to Dr. Claire Temple, a local ER doctor with whom he fell in love, to Jessica Jones, whom he married and had a kid with, to Iron Fist—another hero created to cash in on a movie trend, in this case, the kung fu craze popularized by Bruce Lee—who teamed up with Cage in his title’s 50th issue in 1978, transforming it for the rest of its run into Power Man & Iron Fist.

It’s that run of PMIF #50-125 that most people think of when they think of Cage (and Iron Fist). Brought together by the legendary team of Chris Claremont and John Byrne (best known for their Uncanny X-Men collaboration, but also having done some of the best work with Iron Fist in his own short-lived title as well as Marvel Team-Up), the book later would be the first regular series written by a then-unknown writer named Kurt Busiek (of later Marvels, Avengers, Thunderbolts, and Astro City fame), and also featured the first time the writer/artist team of Dennis O’Neil and Denys Cowan—later to do seminal work on DC’s The Question—collaborated. The final run on the book was written by Jim Owsley (who these days writes under the name Christopher Priest), one of the few African-American writers to actually write Cage in his initial title.

Over the years, Cage has been part of many teams, starting with a stint with the Defenders, briefly being part of the Fantastic Four to replace the Thing when he lost his powers, and more recently being part of several different Avengers teams, even leading them occasionally. He got a solo series in the 1990s, with all twenty issues written by Marc McLaurin (also an African American), and has had periodic miniseries and guest appearances in other series since then. There have also been several attempts to revive the Heroes for Hire concept, both with and without the hero who originated it, with varying degrees of success.

Most recently, he’s been reteamed with Iron Fist in a new Power Man & Iron Fist comic that is explicitly about how they don’t want to team back up again. It’s a delightful series by David F. Walker and Sanford Greene, with a modern take on the heroes for hire that still retains the street-level feel and in particular the humor of the old PMIF comic. On top of that, Marvel’s “Now!” imprint will be releasing Cage!, a comic by Genndy Tartovsky that’s a deliberate throwback to Cage’s 1970s roots.

Cage’s look has evolved over the years. In the 1970s and 1980s he had the afro and the tiara and the yellow shirt and boots. In the 1990s, he has the shaved sides and the occasional do-rag. In the 21st century, he’s kept the bald head and goatee look (also seen on Mike Colter in Jessica Jones and the upcoming Luke Cage series on Netflix).

But throughout all of that, Cage has been a regular guy, born in Harlem, raised in New York, and very much a part of the city. White folks who struggle to make ends meet have Peter Parker from Queens. Black folks who struggle to make ends meet have Luke Cage from Manhattan. That has always been his appeal, from the day he became the first black hero to have his own comic book in 1972 all the way to 2013’s Avengers: Origins: Luke Cage by Michael P. Benson and Adam Glass, when an old man tells Cage: “To see a man of color standing there with the likes of the Defenders, the Fantastic Four, and the Avengers. Means a lot.”

I fell in love with the character of Luke Cage when PMIF crossed over with Daredevil during Frank Miller’s historic first run on the latter title in 1981. Cage and Fist were hired to protect Matt Murdock in Daredevil #178 and then the story continued in PMIF #77 written by Jo Duffy. I got hooked on the title with the very next issue—an intense team-up with El Aguila against the Constrictor and Sabretooth—and it was love at first sight. Looking back, Miller did a horrible job of characterizing Cage and Fist (in particular, he wrote Cage as not being very bright, which is a spectacular misread of the character), but it was enough to get me to buy the other half of the crossover, and Duffy’s writing sucked me right in.

In particular, I kept thinking that PMIF would make a great TV show.

Only took 35 years, but it’s finally happening.

Luke Cage debuts on Netflix this Friday.

Keith R.A. DeCandido has been writing or editing prose versions of Marvel characters on and off since 1994, including the recent “Tales of Asgard” trilogy starring Thor, Sif, and the Warriors Three. He is one of the two Author Guests of Honor at EerieCon 18 in Grand Island, New York this coming weekend, alongside Victor Gischler. Other guests include authors Erik Buchanan, Sèphera Girón, Derwin Mak, Michael Martineck, John-Allen Price, Darrell Schweitzer, Shirley Meier, and Mason Winfield; scientists David DeGraff and David Stephenson; poet David Clink; game developers Lynn Merrill and Alex Pantaleev; and many more. Keith will be doing a Q&A, various panels and presentations, and a reading. Here’s his full schedule.