That is the last time we take directions from a squirrel.

In the early 1990s, the Disney animation department was flying high, after a series of remarkable films that had restored the studio’s critical reputation and—perhaps more importantly—its funding. The success led Walt Disney Studios chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg and the animators and directors to brainstorm even more ambitious prestige projects: an adaptation of a Victor Hugo novel, a continuation—finally—of the 1940 Fantasia, and a film about space pirates that its directors simply would not shut up about. Oh, as a nice follow-up to films set in Africa and China, something set in South America. About, perhaps, the Incas. Featuring songs by no less than singer-songwriter Sting himself.

The film—with the grandiose title The Kingdom of the Sun—had all the elements of a guaranteed Disney hit: romance, comedy, hit songs, and cute llamas. And, its directors promised, it would remain just serious enough to be recognized—like its Disney Renaissance predecessors—as Real Art.

You might notice that The Kingdom of the Sun is not in the title of this post.

What Disney got instead was The Emperor’s New Groove, arguably the first film in the Disney canon to come about more or less by accident, and certainly the only film—so far—to change so radically midway through production. The production process had never, of course, been static. Walt Disney had certainly been known to toss out storyboards; Jeffrey Katzenberg had viciously edited down films; John Lasseter would later overhaul several Disney projects. Animators themselves had a history of making radical changes to the original film concepts of the film before putting anything into production. For this film, however, the changes came well after the film was already in production, with deleterious effects towards the film’s budget.

We know more than usual about the troubled development process for The Emperor’s New Groove, since, in a moment they would later regret, Disney executives agreed to let Sting’s wife Trudie Styler film quite a bit of it. That footage eventually turned into a documentary called The Sweatbox, which appeared in a couple of film festivals and very briefly in an unauthorized YouTube version before vanishing deep into the Disney vaults, where it has a good chance of remaining even longer than those deleted frames from the original Fantasia. This was just enough, however, to allow viewers to take detailed notes of the footage and interviews with the cast and animators, who also gave later interviews about the tumultuous film development.

Which also means that we know I screwed up in an earlier post: in my post on Tarzan, I mistakenly said that The Emperor’s New Groove was apparently originally based on Hans Christian Anderson’s The Emperor’s New Clothes. In fact, the only thing that The Emperor’s New Clothes provided was the inspiration for the title. The original story for The Kingdom of the Sun was a loose—very loose—adaptation of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper set in the Incan Empire.

This idea did not immediately gain favor inside the studio. Setting aside the difficulties of taking a story set in Tudor times and setting it an unspecified period of Incan history, Disney had already done a version of The Prince and the Pauper: a Mickey Mouse short released with The Rescuers Down Under in 1990, and later released in various home video collections, most recently in Disney Timeless Tales, Volume 1 and Disney Animation Collection Volume 3: The Prince and the Pauper; the short is also available through various streaming services. The Prince and the Pauper was cute, popular, and had Mickey, and Disney was really not all that interested in another version.

But since the pitch came not only from then mostly unknown Matthew Jacobs (probably best known to Tor.com readers for his Doctor Who work) but also from Roger Allers, who had just come off a triumphant The Lion King, and since the pitch also promised that the main character would be turned into a llama, which in turn could be turned into a very cute toy, Disney executives gave the film an uneasy nod in 1994. Allers made a few more twists to the story to ensure that it would not be all that much like the earlier Mickey Mouse cartoon, and production officially started in January 1995.

But by mid-1997, production had barely moved forward, despite supposedly inspiring trips to Peru for design ideas, and zoos to look at llamas. Worse, in the eyes of Disney executives, the storyboards and script weren’t all that funny. A new director, Mark Dindal, was brought on to bring new life and zing into the film. Roger Allers reached out to Sting, who began working on a series of songs, and Disney moved back the film for a summer 2000 release.

By 1998, Disney executives were in a fury. From their point of view, The Kingdom of the Sun was nowhere closer to completion, what was completed was terrible and a thematic repeat of a previous Disney short, and without a summer 2000 film, they were in danger of losing several large—and lucrative—promotional deals with McDonald’s and Coca-Cola.

From director Roger Allers’ point of view, The Kingdom of the Sun was a beautiful, epic movie that only needed another extension of six months—maybe a year, tops—to be completed. He begged producer Randy Fullman for an extension. Fullman, who had just had a nasty confrontation with a Disney executive, said no.

Roger Allers, crushed, walked away, leaving Disney at least $20 million in the hole (some estimates are higher) with no film to show for it, depressed animators, and—worse—no film for summer 2000.

An infuriated Michael Eisner gave Fullman two weeks to revamp the film. Fullman ended up taking six months, putting production and animation on full hold. Eric Goldberg took advantage of the hiatus to put a team of animators to work at doing Rhapsody in Blue, a seemingly efficient decision that had the unanticipated end result of delaying production on Tarzan and sending an increasingly outraged Eisner into further fits. With Fantasia 2000 also delayed in production, and contractually bound to IMAX theatres only for its initial theatrical release, Dinosaur (from a completely different team) was moved forward into The Kingdom of the Sun‘s release slot to keep McDonald’s and Coke happy. That, in turn, sent the Dinosaur animators into a panic—and, at least according to rumor, eventually led to the closure of that group, since the rush led to higher than expected production costs.

The chaos did have one, unexpectedly awesome result: it freed animator Andreas Deja to head to Orlando, Florida, where he had the opportunity to join the animators working on a little thing called Lilo & Stitch and, briefly, meet ME. I expect that letting animators meet tourists was not exactly high on Eisner’s list of priorities, but I felt it deserved a mention anyway.

And six months later, Fullman and Dindal finally had a working idea: The Emperor’s New Groove, a buddy comedy kinda sorta maybe set in Incan Peru, featuring a cute llama.

Since millions had already been poured into the film, Eisner gave it one last reluctant go ahead—telling animators to finish the film by Christmas 2000. No exceptions.

Animators hurried.

Sting’s songs—integral to the earlier plot—were mostly dropped, with the exception of one song that managed to find its way to the final credits, singing about things that had not exactly happened in the film. Sting was asked to do one more song for the opening—quickly. The revised film had far fewer characters—faster and easier to animate—so most of the voice cast was quietly fired, with only David Spade (as Kuzco, the main protagonist and llama) and Eartha Kitt (as Yzma, the villain) remaining. Backgrounds and character work were severely simplified: even with the CAPS system to help out, animators were told to limit the number of moving characters on screen at any given time, to speed up the animation process. The new ending—featuring Kuzco sparing his new friend’s village, only to destroy the rainforest right next to it for his personal amusement park—had to be revised yet again, when Sting virulently protested, meaning that The Emperor’s New Groove barely squeaked in front Eisner’s deadline.

Perhaps in reaction or retaliation for all of this, the film the animators finally produced resembled not so much a typical Disney feature, but rather, one of the old cartoons of their great rivals, Warner Bros. The restaurant sequence is almost classic Warner Bros, recalling the rapid fire dialogues of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck and Porky Pig. Other bits—particularly the multiple falls into chasms—have distinct aspects of the old Roadrunner cartoons.

Also perhaps in reaction, The Emperor’s New Groove also has more examples of getting crap past the radar than virtually any other Disney animated feature, including my favorite moment when, if you are paying close attention, the animation spells out “D” “A” “M” “N” as logs fall through the screen. Not to mention the various cheerful moments where the film openly admits that, really, it doesn’t make much sense:

Kuzco: No! It can’t be! How did you get back here before us?

Yzma: Uh…how did we, Kronk?

Kronk: Well, ya got me. By all accounts, it doesn’t make sense.

Followed by a nice map showing that, no, it does not make sense. At all. Something no other Disney film had done or since.

The Emperor’s New Groove was an atypical Disney film in multiple other ways as well. It lacked any hint of romance, although Pacha and Chicha provide an unusual example of a stable, functioning adult relationship—really, the first animated Disney film to feature this since 101 Dalmatians and Lady and the Tramp. (The royal parents in Sleeping Beauty and Hercules’ adoptive parents in Hercules also sorta count, but they barely appear on screen.) It’s a loving relationship, as evidenced by several hugs, mutual support, immediate understanding, and two kids with a third on the way—but it’s not the typical “will the protagonist get the girl/guy” of the previous Disney films.

Meanwhile, the protagonist, in an abrupt departure from previous Disney films and the original script, doesn’t even get a love interest. And in an even larger departure from Disney’s history of largely sympathetic, likable protagonists, Kuzco is, well, none of those things. Most of Disney’s protagonists start out relatively powerless, with even the princesses finding their lives restricted or controlled in various ways. Kuzco is a powerful emperor, so indulged that he even has his own theme song guy, and when the film starts, he’s more or less one of the villains, what with insulting six girls unfortunate enough to be dragged forward as potential new brides, telling his soldiers to toss an old guy out of the window for disrupting his groove, taking a family’s home without compensation because he wants to give himself a birthday gift of a summer house, outright lying to a guy offering to help him out, and indulging in a bit of squirrel cruelty—when, that is, he isn’t whining and feeling very very sorry for himself. Even a later moment depicting him as a very sad and very wet little llama does not exactly do a great deal to pull on my heartstrings.

And oh, yes, Kuzco also fires a long time advisor without notice. Sure, the advisor—Yzma, voiced by Eartha Kitt with complete glee—is the sort of person prone to having conversations like this:

Yzma: It’s really no concern of mine whether or not your family has—what was it again?

Peasant: Food?

Yzma: HA! You really should have thought about that before you became peasants!

So, not exactly the nicest, most sympathetic person around. On the other hand, Kuzco isn’t firing Yzma for her failures to understand the critical importance of food, but because she’s more than once taken over his job. Ok, again, sounds bad, but the opening montage rather strongly suggests that she’s just stepping into a major leadership vacuum. About the only thing we see Kuzco doing that’s even mildly related to sound governance is stamping the foreheads of babies with kisses and cutting a few ribbons here and there wearing a very bored expression.

Meanwhile, Yzma is at least listening to peasants, if not exactly trying to solve their problems. She’s also a skilled scientist, able to do actual transformations, and is fairly intelligent—if not exactly great at choosing intelligent underlings. As she notes—and no one contradicts—she’s been nothing but loyal to the Empire for years, dedicating her life to it. In her defense, she initially takes her—justified—anger about her termination out on the many, many statues of Kuzco instead of Kuzco himself. She also refrains—well, mostly refrains—from telling Kronk what she really thinks about his spinach puffs. And if some of her Evil Plans are just slightly over-elaborate, she’s also severely practical, choosing to poison Kuzco to save on postage, a decision we can all applaud.

I also approve of her ability to take time for dessert.

Also, let’s face it, she has the BEST ENTRANCE TO A SECRET EVIL LAIR EVER (even if it does seem ever so slightly inspired by the hope of creating a later theme park ride.)

So. Yes. YZMA.

Plus, she is tragically dependent on Kronk, who is the sort of retainer who is often unable to know if he’s being asked to hit someone over the head or pass the broccoli, a confusion I think we can all sympathize with. Not to mention that he tends to be far more interested in cooking, the feelings of squirrels, and playing jump rope than in killing transformed llamas, again, a feeling I think many of us can sympathize with. Their relationship—and Patrick Warburton’s deadpan delivery of Kronk—is probably the highlight of the film.

And I love the little nod to Eartha Kitt’s previous role as Catwoman, when she’s transformed into an adorable little kitten at the end of the film.

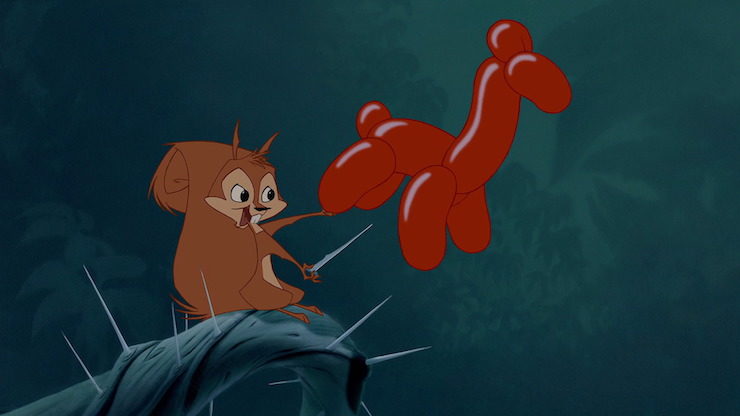

I have to say that the other pairing of Kuzco and Pacha, the peasant Kuzco plans to uproot, who then ends up rescuing Kuzco after his llama transformation, is not quite as successful, let alone hilarious, partly because Pacha often seems too trusting and naïve for words, and partly because David Spade is, well, David Spade. Portions of this occasionally drag, especially in comparison to the zinging Yzma and Kronk bits, who can even manage to make a little detour with a somewhat traumatized squirrel zip along.

But if the pacing can be a bit uneven, and the rushed animation is not exactly one of Disney’s highlights, it’s still well worth watching, especially with the subtitles on, so you don’t miss subtitles like this:

[POURING DRINK]

[OPENING POISON STOPPER]

[POURS POISON IN DRINK]

[EXPLOSION]

Also, the squirrel is pretty adorable.

The Emperor’s New Groove brought in $169.3 million at the box office—a seemingly respectable amount, but a total far below the box office hits of the 1990s, and a huge disappointment after the multiple production delays and issues. The disappointment may have been thanks to its Christmas opening, the lack of a sympathetic protagonist, the lack of the standard ubiquitous Disney power ballad, the decision by Disney marketers to focus their marketing dollars on 102 Dalmatians instead. Or simply that even after Hercules, the film’s comedic, high energy tone was not what audiences expected or wanted from Disney at the time. I can’t help wondering if Disney executives regretted stepping in and changing the tone of the film, fun though the final result was.

The film was, however, just successful enough to spawn a direct to video sequel, Kronk’s New Groove. Patrick Warburton again got to shine, but like pretty much all of the direct to video sequels, this is otherwise a dull affair, easily skipped. It in turn sold enough units, however, for Disney to later release a TV series, The Emperor’s New School, which ran for two years on the Disney Channel. Disney also released a video game and the usual assorted merchandise.

But as noted in a previous post, the box office total was an alarming sign for Disney.

The next film would not qualm their fears.

Atlantis: The Lost Empire, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.