In this monthly series reviewing classic science fiction books, Alan Brown will look at the front lines and frontiers of science fiction; books about soldiers and spacers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

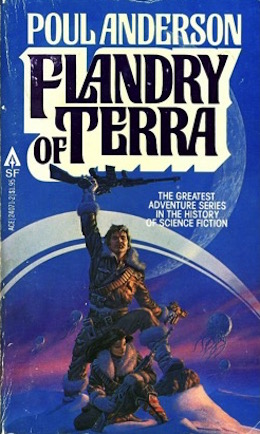

Sometimes a cover painting is all it takes to reel you in. The paperback copy of Flandry of Terra had a glorious cover by Michael Whelan that metaphorically jumped off the shelf of the bookstore and grabbed me by the scruff of the neck. While being a true and accurate depiction of characters from the story, the artwork also evoked some of Frank Frazetta’s best work: there was Flandry in a heroic pose, wearing cold weather gear and signaling to someone in the distance with his rifle, with a beautiful, similarly-clad woman crouching at his feet. A planetary ring arched in the background while airborne jellyfish floated above the wintry terrain. The author’s name was the icing on the cake: I was well acquainted with Poul Anderson’s work, and here was a whole new, exciting character—one who was completely unfamiliar to me. I had to buy this book, take it home, and see what I had been missing. And so it was, sometime in the early 1980s, that I first met Dominic Flandry. I was in for a treat.

In those days, it was impossible to be a science fiction fan and not have heard of Poul Anderson (1926-2001), then at the height of a career that, before it was over, would garner seven Hugos, three Nebulas, a SFWA Grand Master Award, and a host of other honors. Anderson was comfortable in a variety of sub-genres, having written epic fantasy, sword and sorcery, time travel, serious scientific extrapolation, adventure, and even humorous stories. My own knowledge of his work primarily involved tales that appeared in Astounding/Analog, stories of the Polesotechnic League, and master traders Nicholas van Rijn and David Falkayn. But with the introduction of Dominic Flandry, I found that Anderson’s future history (also referred to as the “Technic History”) spanned an even wider sweep of time. It not only described the growth of an interstellar human civilization, but in the tales of Flandry, showed the degeneration of that civilization into an empire on its way into oblivion. In charting the course of his future history, Anderson was obviously influenced by historians interested in long-term patterns of cultural growth and decline, evoking themes posited by those such as Gibbon, Toynbee, and Spengler.

Many have remarked that with this character, Anderson had created a spacefaring version of James Bond, but when you compare publication dates, Flandry’s introduction actually predates Bond’s. In my opinion, though, the closest literary analog of Flandry is C. S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower, the subject of a series of extremely popular books that followed an entire fictional career, the most famous of which were the original trilogy written in the late 1930s: Beat to Quarters, Ship of the Line, and Flying Colours. The popularity of the series initiated a modern sub-genre of historical fiction centered on the adventures of 18th and 19th century naval officers, paving the way for authors like Patrick O’Brian, James L. Nelson, and more recently Julian Stockwin. Dominic Flandry is not an exact match to Horatio Hornblower, of course—Hornblower was a warship commander, while Flandry an intelligence agent. But like Hornblower, Flandry’s first appearance was as a captain at the height of his powers (in the story “Tiger by the Tail,” which appeared in Planet Stories, January 1951). And like Forester, Anderson then went back and outlined the beginning of his hero’s career, and then continued the story into his later years. By the time he was done, Anderson had not only captured the grand sweep of history, but also the scope of an entire lifetime. He was not alone in inventing a Hornblower of the far future, however, with writers such as A. Bertram Chandler, David Weber, and Lois McMaster Bujold all ranking among the science fiction authors who have followed a similar template over a series of books.

Many have remarked that with this character, Anderson had created a spacefaring version of James Bond, but when you compare publication dates, Flandry’s introduction actually predates Bond’s. In my opinion, though, the closest literary analog of Flandry is C. S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower, the subject of a series of extremely popular books that followed an entire fictional career, the most famous of which were the original trilogy written in the late 1930s: Beat to Quarters, Ship of the Line, and Flying Colours. The popularity of the series initiated a modern sub-genre of historical fiction centered on the adventures of 18th and 19th century naval officers, paving the way for authors like Patrick O’Brian, James L. Nelson, and more recently Julian Stockwin. Dominic Flandry is not an exact match to Horatio Hornblower, of course—Hornblower was a warship commander, while Flandry an intelligence agent. But like Hornblower, Flandry’s first appearance was as a captain at the height of his powers (in the story “Tiger by the Tail,” which appeared in Planet Stories, January 1951). And like Forester, Anderson then went back and outlined the beginning of his hero’s career, and then continued the story into his later years. By the time he was done, Anderson had not only captured the grand sweep of history, but also the scope of an entire lifetime. He was not alone in inventing a Hornblower of the far future, however, with writers such as A. Bertram Chandler, David Weber, and Lois McMaster Bujold all ranking among the science fiction authors who have followed a similar template over a series of books.

Dominic Flandry is a fascinating character, and a man of contradictions. He is vain and cocky, but for good reason, as he is keenly intelligent, clever, and physically capable. Flandry clawed his way from an obscure birth to the heights of imperial society, and climbed up the naval ranks from ensign to admiral, with a knighthood granted along the way. He is a hedonist who dresses like a peacock and loves nothing more than drinking and parties, but is devoted to his work in service to the Empire with a monkish intensity of purpose. He is a lover of women and attracts many in his travels, but his work does not allow him to remain with any of them for long, nor to put down any roots. He almost always prevails, but in the end is a tragic figure: no matter how successful he is, he knows the forces of history are inevitably tearing his precious empire apart.

Anderson was a student of Norse mythology, and Flandry is like one of the heroes of the ancient sagas: noble, always striving, but in the end doomed to the fate that awaits all men. Underneath all the adventures and derring-do, Flandry’s life has a melancholy undertone that gives it weight and gravitas. I often wondered why Flandry never appeared in Analog like so many of Anderson’s other characters, but I suspect that the character and his romances were not to the taste of editor John Campbell, who seemed somewhat prudish in his avoidance of sex in the stories he published. Another reason might be the fact that many of the Flandry stories, while they have science fiction settings, do not always have plots that resolve around science and technology, but instead are often rooted more in politics and adventure.

Anderson was a student of Norse mythology, and Flandry is like one of the heroes of the ancient sagas: noble, always striving, but in the end doomed to the fate that awaits all men. Underneath all the adventures and derring-do, Flandry’s life has a melancholy undertone that gives it weight and gravitas. I often wondered why Flandry never appeared in Analog like so many of Anderson’s other characters, but I suspect that the character and his romances were not to the taste of editor John Campbell, who seemed somewhat prudish in his avoidance of sex in the stories he published. Another reason might be the fact that many of the Flandry stories, while they have science fiction settings, do not always have plots that resolve around science and technology, but instead are often rooted more in politics and adventure.

In choosing the book Flandry of Terra for this review, I admittedly used my heart and not my head. I could have started at the beginning of the series with Ensign Flandry. Or I could have picked the volume that brings the series to an emotional climax, A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows. But instead I picked the point where I first started reading the series, which in retrospect, was as good a place as any. Flandry of Terra is an omnibus, consisting of three novelettes. These tales find Captain Sir Dominic Flandry at the height of his powers, and each stands alone as a separate narrative that gives the reader a solid sense of its hero and the nature of his adventures.

The first tale, “The Game of Glory,” originally appeared in the March 1958 edition of Venture Science Fiction. The whispered confession of a dying soldier leads Flandry to the watery world of Nyanza in search of rebels. Nyanza is dominated by a people of African descent who are the shipmasters and traders, while a German minority of landlubbers maintain the world’s ports and industry. Flandry’s suspicions of trouble are confirmed when he finds the imperial ambassador recently murdered. He soon sails off with a beautiful and scantily clad shipmaster, Tessa, to the island that is home to the dead soldier’s family. Flandry, always eager to woo women even though he knows he must leave them behind, grows close to Tessa during their voyage. When he meets the father and brother of the dead soldier, John and Derek, he clashes with Derek, who has romantic interest in Tessa. Flandry finds himself the object of a murder attempt and discovers that there is indeed a plot afoot. An agent of the rival Merseian Empire has been arming a nearby island, which has triggered an arms race and unrest across the planet. When John is murdered, his grieving son Derek swallows his dislike to aid Flandry, who has to not only neutralize the rival island, but find and take out the enemy agent. Flandry plays, as he often does, the role of a spoiled and clueless imperial, but beneath it all he is lying, scheming, and manipulating everyone around him to achieve his goal of fending off the Long Night of imperial decline for at least a little longer.

The second novelette, “A Message in Secret,” was reprinted from the December 1959 issue of Fantastic Science Fiction Stories. The story finds Flandry arriving on the planet Altai, a world well off the beaten track of normal commerce—a cold planet dominated by cold and snowy plains. He is a passenger on a Betelgeusean freighter (the only race that that is known to trade with Altai). The planet has been colonized by people from Central Asia, who have adopted a nomadic lifestyle similar to the one that their ancestors practiced on Earth. Around the planet’s single spaceport, Flandry observes weaponry that makes it obvious that the local Khan, Orleg, is in league with the Merseians. Though he quickly adopts his standard persona of a clueless, vapid imperial, he has seen too much and is soon imprisoned.

The second novelette, “A Message in Secret,” was reprinted from the December 1959 issue of Fantastic Science Fiction Stories. The story finds Flandry arriving on the planet Altai, a world well off the beaten track of normal commerce—a cold planet dominated by cold and snowy plains. He is a passenger on a Betelgeusean freighter (the only race that that is known to trade with Altai). The planet has been colonized by people from Central Asia, who have adopted a nomadic lifestyle similar to the one that their ancestors practiced on Earth. Around the planet’s single spaceport, Flandry observes weaponry that makes it obvious that the local Khan, Orleg, is in league with the Merseians. Though he quickly adopts his standard persona of a clueless, vapid imperial, he has seen too much and is soon imprisoned.

A beautiful woman, Bourtai, comes to visit him. She is daughter of a rival Khan who is also a prisoner of Orleg. Her visit forces Flandry into action, and they escape into the wilderness. After a brutal chase, they find Bourtai’s people. Although he has escaped, Flandry is in deep trouble. He desperately needs to get a message back to the empire, and with the spaceport under tight control, getting out himself is impossible. The solution to his problem involves the desecration of a temple, securing aid from a race of flying jellyfish creatures, and some incomprehensible military maneuvers. During these adventures we see that, beneath his vapid exterior, Flandry is a true warrior, as durable and tenacious as they come. And once again, a desirable woman must be left behind as he follows the call of duty.

The final novelette in the collection, “The Plague of Masters,” appeared in Fantastic Stories of Imagination in the December 1960 issue. This story is a bit deeper than the first two, and has a strong edge of social satire, showing the dangers of corruption and stagnation when government bureaucracy runs amok. It’s set on the planet of Unan Besar, which is on the warm and swampy side and is colonized by people from Malaysia. Flandry goes there to find out why this planet has stayed well off the beaten track, but instead of outside interference, he finds the world gripped by a totalitarian state. There is a deadly bacterial plague on Unan Besar that requires regular medication to keep it at bay. The Biocontrol organization, which regulates production of the medicine, has used their power to take control of the planet’s government. They also control the medicine that can cure the disease entirely—essential to anyone who wants to leave the planet alive. Warouw, the government agent who is assigned to Flandry, takes him to meet the planetary leaders, but they soon sees through his clueless tourist act and try to take him prisoner. Flandry escapes, and strikes out in search of some sort of illegal underground that can sell him the medicine he needs to stay alive.

Fortunately, he finds his criminals in the form of a beautiful woman, Luang, and her hulking bodyguard, Kemul. Luang tells Flandry he must pull his own weight, and we see how Flandry, exiled with only the clothes on his back, manages to land on his feet, using his professional talents to lie and con his way into a great deal of money. They travel to a far away land and Luang tries to convince Flandry to stay with her and start a new life, but the pull of his duty is too strong, and Flandry never stops plotting to escape. Modern technology on other planets could easily and cheaply synthesize the medicine the people need, and he wants to free this planet from the grip of its Biocontrol overlords, then return home to his own life. Warouw, however, proves to be one of Flandry’s most tenacious opponents, and soon recaptures him. An act of kindness on Flandry’s part proves to be the key he needs to escape captivity again, and he devises a plan to leave the planet and return with all the medicine the people will need.

Fortunately, he finds his criminals in the form of a beautiful woman, Luang, and her hulking bodyguard, Kemul. Luang tells Flandry he must pull his own weight, and we see how Flandry, exiled with only the clothes on his back, manages to land on his feet, using his professional talents to lie and con his way into a great deal of money. They travel to a far away land and Luang tries to convince Flandry to stay with her and start a new life, but the pull of his duty is too strong, and Flandry never stops plotting to escape. Modern technology on other planets could easily and cheaply synthesize the medicine the people need, and he wants to free this planet from the grip of its Biocontrol overlords, then return home to his own life. Warouw, however, proves to be one of Flandry’s most tenacious opponents, and soon recaptures him. An act of kindness on Flandry’s part proves to be the key he needs to escape captivity again, and he devises a plan to leave the planet and return with all the medicine the people will need.

These three stories showcase the talents of Poul Anderson at his best. The planets and interstellar worlds are designed with great care and scientific consistency, and the alien species and ecologies are convincing. Anderson also conceived his societies with great attention to history and sociology. It was admittedly a bit jarring to encounter so much smoking going on—a casual habit that has almost disappeared from literature and film in recent years—and the gender roles seem a bit archaic to the modern viewpoint. While it might not seem so at first, however, the women Flandry meets are strong characters in their own right: Tessa is a government official, Bourtai fights right alongside the men of her tribe, and Luang is a clever and accomplished criminal outsmarting an oppressive regime. Flandry sometimes behaves like a cad, prejudiced and sexist in a way that jars modern sensibilities; but with all his flaws, he remains a compelling character whose adventures make for exciting reading.

I was saddened to visit a large bookstore recently and find not a single book by Poul Anderson on the shelves. These days, books seem to disappear from the shelves so quickly that it can cause people to miss out on older works that are well worth reading. Whether you search on the internet, the library, or in a used bookstore, Poul Anderson’s tales of Dominic Flandry are well worth seeking out. You will not be disappointed.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for five decades, especially science fiction that deals with military matters, exploration and adventure. He is also a retired reserve officer with a background in military history and strategy.

I have what I’m pretty sure is a complete collection of the Technic History, and though Flandry is a bit too Bond-like to be a favorite, his stories can be entertaining. The editions I have of the earlier Flandry stories seem to have been rewritten by Anderson later in life to make the science a bit more plausible and less pulpy, but I’m not sure. It’s Anderson’s hard-science and historical knowledge and rich worldbuilding that I’ve always found most interesting.

The first time I read these, I found myself thinking that there was a missed opportunity: Imagine an early-1970s Flandry TV series starring William Shatner. I think he would’ve been a good fit for Flandry, a cocky, womanizing, two-fisted space hero with a keen intellect and more empathy than he lets on. Although these days, when I read the Flandry stories, I prefer to imagine Bruce Campbell in the role.

This is as good a summary of “Flandry” & the reasons why it deserves to be taken seriously as any I’ve read. Yes, the “Flandry” books are — on the surface — light-hearted pulp full of derring-do and enjoyable wisecracks. But you’re absolutely right that there’s more to them than that, and that Flandry’s story is fundamentally tragic. Moreover, Flandry himself is well aware of it: he knows that the Empire will fall — and that it deserves to — but he knowingly sacrifices his own life and everything he loves to holding off the inevitable collapse just a little longer, so that a few more sentient beings can live out their lives in peace before civilization collapses (he articulates it in precisely these terms in one of the books). That’s strong stuff.

The other standout element of the “Flandry” cycle is his recurrent antagonist, Aycharych. Again, Aycharych is superficially a delightful pulp villain — cultured and devious, an urbane straight man who provides the perfect foil for some of Flandry’s best quips. But when his motivations and the full extent of his activities become clear, he is revealed as something very much darker. Thinking about it now, it occurs to me that Aycharych is quite literally Flandry’s mirror: he is engaged in the same vain struggle to preserve something that he values, whatever the cost to others. The parallels are so close that Aycharych’s amorality is grounds for asking whether Flandry is, after all, acting morally or not.

Aycharych is an instance of what Joseph Campbell called the Tyrant Holdfast — the ultimate villain, who is evil “not because he keeps the past, but because he keeps.” And in the Hero’s Journey, there’s always the threat that if the hero cannot renounce what he is won, then he may in turn become the tyrant. Flandry could become — may already be — Aycharych. I have no idea whether Anderson was thinking of Campbell’s monomyth when he wove this particular mythic thread into his story, but it’s there anyway and part of the power of “Flandry” derives from it.

In answer to ChristopherLBennett, I think Chris Pratt might be able to carry off the young Flandry to near-perfection. I’m not sure which actor would have the necessary combination of levity and gravity for the older, wearier Flandry. Clive Owen might do it, but I have the sense that he’s better at “gritty” than “debonair”.

I know that if someone made a movie or a miniseries out of “Flandry” and did it right, I’d watch the hell out of it.

@3/angusm: I dunno… I think part of the reason I imagine it as a ’60s or ’70s TV series is because it has a sensibility that’s a better fit to that era. It’s very much a product of its time.

I confess “Hornblower in space” isn’t the first thing that comes to mind when I think of Flandry but this is perhaps because A. Bertram Chandler’s John Grimes is Hornblower in space. I recall Anderson’s initial model was Leslie Chartersis’s Simon Templar, aka “The Saint”; I also tend to get a bit of Belisarius or some other “Last Roman” type in his makeup.

I would have liked to have seen David Niven play Flandry.

@5/SchuylerH: And of course Captain Kirk is Hornblower in Space. Gene Roddenberry was very much inspired by the Hornblower novels when he created Star Trek. Maybe that explains why I thought Shatner would’ve been a good fit.

Great review. I’ve read some of Poul Anderson’s books and he is awesome. I’ve looked at this Flaundry novels before, and they look like my kinda stuff, I think a lot of them are available as eBooks. I’ll have to see what I can find. Thanks.

This is a pretty good pick as a starting point for Flandry. Some of the stories about younger Flandry were written later and, for me, don’t quite work as well. And the stories about the much older Flandry, especially those with his daughter, go to some weird and dark places. Anderson flirted with the braineaters and those later stories are where they most showed their influence.

Like Schuyler @5, I think of John Grimes when it comes to Hornblower in space, while James Bond in space would be Retief (albeit a parody version). And I’d say that both of those have possibilities as future subjects for this series.

For completeness, any list of influences on “Flandry” should include P.G. Wodehouse, as Chives — Flandry’s green-skinned humanoid manservant — is clearly a parody of Jeeves. More generally, Anderson also draws on historical events and characters.

I wonder about the name Aycharaych. It’s basically a phonetic spelling of “HRH,” as in “His/Her Royal Highness.” I’ve always wondered if it was a pun or reference to something.

@1 If you have the seven volume set that Baen put out a few years ago, then yes, you have the entire Technic History in a single collection. And in the volume pictured above, Captain Flandry, Hank Davis (who collected the stories for the collection) stated that Anderson had indeed rewritten the tales somewhat for their appearance in Flandry of Terra, and another Ace collection that appeared at about the same time.

@2 If they let me continue this series long enough to revisit some of my favorite authors, I would love to review A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows, because Aycharych is such an intriguing antagonist, one of the best in SF.

@11/Alan: No, I just have a bunch of old used paperbacks that I accumulated over a few years. Let’s see, in roughly chronological order, I have:

The Earth Book of Stormgate

The Trouble Twisters

Trader to the Stars

Satan’s World

Mirkheim

The People of the Wind

Ensign Flandry

Flandry (omnibus of A Circle of Hells and The Rebel Worlds)

Flandry of Terra (same edition shown in this post)

The Day of Their Return

Agent of the Terran Empire

A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows

A Stone in Heaven

The Game of Empire

The Long Night

The Night Face

Plus various other Anderson books in other universes, though Technic is the only complete series of Anderson’s that I have.

@12 That sounds like a pretty complete collection–I have a lot of those same paperbacks myself. I picked up the Baen collections as well back when Borders Books was going out of business, as some of the original paperbacks were getting a bit tattered and worn. And the Baen collections have some nice essays and timelines in addition to the stories themselves.

I have liked Anderson’s entire Future History since I first found the SF section in the library. I never saw Flandry as Hornblower, for me that would be Grimes. A. Bertram Chandler had Flandry make an appearance in the Grimes book The Dark Dimensions. Great fun for a fan of both series.

I’m sorry to keep popping up like this, but I’m binge reading your columns. My intro to Flandry came when I picked up Ace Double D-479 in 1960, so I’d read Flandry BEFORE reading Bond, who I started with in the summer of 1963 soon after seeing Dr. No. I actually suspect that my love of Flandry left me ready to enjoy Bond. Embarrassingly, I don’t remember whether or not I read the Tucker, on the flip, although I quite loved his The Year of the Quiet Sun when it was published as an Ace Special.

Earthman, Go Home! (dreadful title, the same story was serialized in Fantastic as A Plague of Masters, a MUCH better title which I suspect was Poul’s preferred one) turned me on to Anderson, Flandry and Southeast Asian culture since the setting was a planet influenced by, I believe, Thailand. Four years later, not entirely coincidentally, my mother and I were eating Indian & Indonesian food at the NY Worlds’ Fair and listening to Gamelan music at the Indonesian Pavillon. I found my way to Thai not much later. I’ve loved all 3 cuisines ever since. But my tale does loop back to SF. I read Divine Endurance because I’d found that it took place in a far future Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore, plus it had a cat, and that book turned me into a rabid fan of Gwyneth Jones. I was reading the Hornblower books at basically the same time.

Anyway, I picked up the 2 Chilton Flandry collections Agent of the Terran Empire & Flandry of Terra in 1965, and Ensign Flandry (a full on novel, and a 1st edition to boot) in 1966. I met Poul briefly at a party at Tricon in Cleveland, which as my first Con, let alone Worldcon, in 1966. I told him how much I liked his Flandry books at which point the conversation kinda flagged. Important lesson: If you want to meet one of your idols, prepare something to talk about in case they’re as shy as you are. This has stood me in good stead later, for which I can credit Poul Anderson.

@15 You have nothing to apologize for, Bill, I am enjoying reading your observations on the books.

@@@@@ 2: Aycharych is an instance of what Joseph Campbell called the Tyrant Holdfast — the ultimate villain, who is evil “not because he keeps the past, but because he keeps.” And in the Hero’s Journey, there’s always the threat that if the hero cannot renounce what he is won, then he may in turn become the tyrant. Flandry could become — may already be — Aycharych. I have no idea whether Anderson was thinking of Campbell’s monomyth when he wove this particular mythic thread into his story, but it’s there anyway and part of the power of “Flandry” derives from it.

I don’t know if Poul ever read Campbell. He once recommended Eliade’s Shamanism to me. So he was familiar with the territory. I never raised a conversational subject with him, where he didn’t know more about it than I did. The man was scary smart. I bet he had read Campbell.

@@@@@ 5: I recall Anderson’s initial model was Leslie Chartersis’s Simon Templar, aka “The Saint”;

When he was in the SCA, Sir Bella of Eastmarch regularly challenged a friend. Hap fought for The Saint. Poul supported Mr. Teal.

If I wanted to cast Flandry, and my Tardis was working, I’d hijack Roger More from his days playing The Saint.

Of course, they tried to hijack More to play Bond during those years, and they didn’t manage that.

@@@@@ 8: This is a pretty good pick as a starting point for Flandry. Some of the stories about younger Flandry were written later and, for me, don’t quite work as well. And the stories about the much older Flandry, especially those with his daughter, go to some weird and dark places. Anderson flirted with the braineaters and those later stories are where they most showed their influence.

Poul spoke slightingly about those early Flandry stories. “He rushes to the conclusion in time for his next beer.” But the tone of all his work changed over the years.

@@@@@ 15: I met Poul briefly at a party at Tricon in Cleveland, which as my first Con, let alone Worldcon, in 1966. I told him how much I liked his Flandry books at which point the conversation kinda flagged. Important lesson: If you want to meet one of your idols, prepare something to talk about in case they’re as shy as you are. This has stood me in good stead later, for which I can credit Poul Anderson.

I set a poem from one of Poul’s stories to music. When I played it a party, a friend asked, “Has Poul heard that?”

I said, “I offered to sing it for him, but he wasn’t interested.”

She said, “He’s hard of hearing. He probably didn’t understand you.” So she dragged me to where Poul was and insisted he listen. He smiled through the performance, and thanked me.

A lot of his shyness was lack of understanding what was said to him.