Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

Today we’re looking at Sarah Monette’s “Bringing Helena Back,” first published in the February 2004 issue of All Hallows. Spoilers ahead.

“I have dreams sometimes, in which I throw the book again on the fire, but this time it does not burn. It simply rests on top of the flames, its pages flipping randomly back and forth. I can feel my hands twitching and trembling with the need to reach into the fire to rescue it.”

Summary

Kyle Murchison Booth, socially awkward but with a remarkable gift for breaking ciphers and penetrating mysteries, has recently become an archivist at the Samuel Mather Parrington Museum. After a separation of ten years, his college friend Augustus Blaine shows up asking for help deciphering a book he’s purchased at great expense. The slim leather-bound quarto is worn and nameless–someone’s burned its title off the spine. What’s the book about, Booth asks. Blaine’s reply is oblique but telling: Why, it describes how to bring Helena back.

Oh, necromancy. Which leads us to some backstory. Though both scions of American aristocracy, Booth and Blaine were seeming opposites when they met as freshmen, Booth bookish and introverted, Blaine charismatic and superficially brilliant. But Blaine’s “relentless, bright-eyed interest in everything” wasn’t feigned; perhaps he needed Booth to be his auditor for topics less collegiately fashionable than athletics and booze. For his part, Booth was drawn to Blaine like drab moth to scintillating flame, and ended up falling in love with him.

This love went unconsummated and indeed undeclared. In their junior year, while they visited a mutual acquaintance’s house, Blaine met his amorous fate in Helena Pryde. Tall, slender, with a stunning fall of ruddy gold hair, she seemed a changeling in her amiable family. Her high, breathless voice especially irritated Booth, for its childlike innocence was “a deception worthy of the Serpent in Eden.” Calculating and predatory, she targeted Blaine at once. Before the visit was done, the two were engaged.

After the marriage, Booth followed his friend in the society papers, where now-lawyer Blaine appeared as an accessory of his much-photographed wife. Blaine didn’t complain—the Blaines were always protective of the family reputation. Even they, however, couldn’t cover up the scandal when Helena died of a cocaine overdose while trysting with her lover Rutherford Chapin. Blaine became a recluse, obsessed with the idea of bringing Helena back. He immersed himself in the black arts; one shady dealer obtained for him the current tome of interest.

Dubious but eager to keep Blaine back in his life, Booth agrees to tackle the titleless book. A real friend, he’ll later think, would have advised the man to burn the abominable thing. For he soon realizes the cipher is one invented by 16th-century Flemish occultists, obscure but not difficult to unravel. He won’t reveal the book’s true title, but like the occultists refers to it as the Mortui Liber Magistri. That translates to Book of the Master of the Dead, or maybe Book of the Dead Master. Uh oh, either way. Mortui instantly captures Booth and doesn’t release him until morning, when he finishes his translation. He calls Blaine under the book’s thrall and says: “I know how to do it.” Then he sleeps, to wake up screaming.

That night he and Blaine perform the ritual in Blaine’s basement. Blaine has obtained graveyard earth and entrails to burn. He persuades Booth to supply the human blood. Maybe that selfish failure to give all for Helena is what dooms him. Powered by Blaine’s Latin spell-chanting, the ritual works, and Helena materializes on the ritual obsidian slab, standing with her back to the friends, her hair “a torrent of blood and gold.”

Blaine calls to her, but Helena won’t turn. “Where’s Ruthie?” she demands. “I want Ruthie.” Booth thinks this scene must be a distillation of their marriage, Blaine pleading, Helen looking away for something else. Helena keeps taunting Blaine with calls for her lover. At last, for all Mortui’s dire warnings, Blaine steps into the spell-circle that encloses her. Helena turns, her face gray and stiff. She’s still dead, and yet “animate.” Blaine, Booth sees, has summoned no living woman but her spiritual “quintessence” of heartless selfishness, a virtual demon. Before Booth can drag him to safety, Helena seizes Blaine and kisses him. Blaine falls dead at her feet.

Now Helena taunts the cowering Booth. She can’t talk him into the circle, can she? But she bets Blaine could have. She and Blaine both had their little lapdogs. Hers was Rutherford—Ruthie—Blaine’s was “Boothie.” Spurred by his hatred, Booth spits back that Helena’s “lapdog” killed her. Her characteristic smirk is a rictus on her dead face: So what? Now Blaine’s lapdog has killed him. They’re even.

With the caster dead, the ritual fails. Helena fades away, but not without a final jab: Is Boothie going to try calling Blaine back?

What Booth must do first is clean up all signs of the ritual. When Blaine’s body is discovered days later, all assume he died of a heart attack brought on by emotional stress. Booth’s in the clear, except to himself. Helena was right—he killed his beloved.

Will he bring him back? A voice like Blaine’s whispers in his head that the ritual would work differently this time. Blaine’s his friend. Blaine wouldn’t hurt him. But Booth knows Helena would never give him an idea that would make him happy. He hurls Mortui and his notes into the fire. At first he’s afraid the book won’t burn, but at last its brittle pages ignite.

The sound of the book burning is like the sound of Helena’s laughter.

What’s Cyclopean: Most of Booth’s descriptions are spare and precise. So when he talks about “gibbering” and “abominations,” you know he’s not kidding around.

The Degenerate Dutch: “Helena” focuses on upper crust prep school WASPs, and the picture it paints isn’t kind.

Mythos Making: No elder gods, no Deep Ones or R’lyeh, but a thoroughly Mythosian worldview: “I hold no particular brief for the rationality of the world, but that this vile obscenity should actually have the power to bring back the dead seems to me a sign not merely that the world is not rational, but that it is in fact entirely insane, a murderous lunatic gibbering in the corner of a padded cell.”

Libronomicon: The Mortui Liber Magistri is not the book’s real title. We’re not going to tell you the real title. Blaine does mention owning the Book of Whispers, though Booth suspects/hopes he’s actually got the 19th century fake.

Madness Takes Its Toll: After his wife’s death, Blaine becomes slightly obsessed with necromancy.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

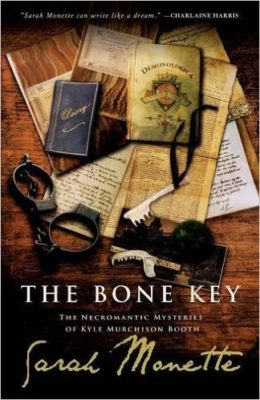

The Kyle Murchison Booth stories stand high in my personal canon of modern Lovecraftiana. They’re also potato chips: I intended to read only the first story for this post, and ran through the whole of The Bone Key in an evening. So this post is likely to have mild spoilers for the whole collection. And I’m being good and not even talking about the chapbooked World Without Sleep, which is to “Bringing Helena Back” as “Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath” is to “The Statement of Randolph Carter.”

The Booth stories are notable for being unmistakably Lovecraftian while having almost no cosmic in their cosmic horror. Kyle’s world is claustrophobic, his stories personal. There are no aliens, no hungry gods, no deep time. What they do have are cursed tomes aplenty, ghosts and ghouls and incubi, a museum fit for Hazel Heald—and a narrator who isn’t quite Lovecraft and not quite a Lovecraftian narrator, but deconstructs both with a scalpel.

“Helena” is Booth’s first story. The central relationship is unhealthy, unequal, and a lot like the one Randolph Carter’s describes in his original “statement”. But Carter’s deep in the throes of combat-born PTSD; Booth’s traumas go back to childhood with a foster family out of Roald Dahl. Blaine’s his “only friend” and surreptitious crush. He’s never learned to talk to girls, boys, or anyone who isn’t actively geeking about a shard of pottery. Still, like Carter, he’s braver than he looks. He’s a necromancer of some skill if little predilection, and familiar with the nastier corners of the library catalogue. Later we’ll see that he’s unwilling to turn away from mysteries even when they make him miserable, particularly if someone (or something) needs help—or just a sympathetic witness.

The titular Helena is a nasty enigma, and the only woman in the story. Other and more sympathetic women show up later, but here Booth’s entirely Lovecraftian in how he thinks about gender. Perhaps more so—he’s at least dimly aware that Helena is a direct rival for Blaine’s affections, and equally aware that nothing he can do would earn him her place. The best he hopes for is respect, and he doesn’t hold out much hope of that. Sexual tension is not a deeply buried subtext for Booth, and it’s not hard to guess what he’s repressing. But it’s not only love he longs for. Simple friendship seems equally unreachable.

The Samuel Mather Parrington Museum is deliciously prototypical. We see a little of Kyle’s work here; later we’ll learn that it houses a number of interesting objects in its collection. More and stranger can be found in the poorly-catalogued sub-basements, where no one goes alone after dark. One suspects that in the modern day, the Parrington has not followed the trend of offering sleepovers to kids.

The story’s necromancy is understated and creepy. Lovecraft’s narrators sometimes fall prey to the trope of “Let me tell you in detail about this unspeakable thing that I couldn’t possibly tell you about.” Booth actually does hold back, sharing only enough detail to convince us that, no, we really don’t want to know the actual title of that book. We definitely don’t want to know what happens in the indescribable ritual. The results are alarming enough. And—one more difference from Carter—he’s not a mere witness to his friend’s fate, but fully complicit. His hands can never be as clean as those of a more passive narrator. That theme continues across the stories: no matter how much Booth holds back from the world, he can’t untangle himself from its most terrifying aspects.

Anne’s Commentary

I’m glad I bought The Bone Key instead of one of the anthologies in which “Bringing Helena Back” appears. Having made Booth’s acquaintance, I’m eager to follow his further adventures. Also, this gave me a chance to read the (for us terminally bookish types) delightful material that introduces the collection, including the author’s first edition preface and the description of the Kyle Murchison Booth papers archived in the Samuel Mather Parrington Museum. The latter was penned by Dr. L. Marie Howard, MSLIS, Ph.D., Senior Archivist at the Museum, who I’m sure would make a charming companion on a tour of antique bookstores.

Monette’s introduction lays her inspiration cards on the table, with éclat. She has devoured both M. R. James and H. P. Lovecraft and admires their “old school horror of insinuation and nuance.” Less satisfying to her are their neglect of in-depth characterization and, well, sex (meaning both full-bodied female characters and, well, sex.). She finds herself “wanting to take apart their story engines and put them back together with a fifth gear, as it were: the psychological and psychosexual focus of that other James.” You know, Henry, the screw-turner.

“Bringing Helena Back” was an attempt to build such an engine, and a successful one too, I say. Kyle Murchison Booth is as finely wrought and complex as the pocket watch he might himself carry. Monette writes his direct inspiration was the Randolph Carter of Lovecraft’s “Statement,” a “weak, unstable narrator in thrall to his brilliant reckless friend.” He’s also in love with his reckless friend, and in deep (perhaps semi-blinded) hate of his friend’s wife. What a triangle Booth and Blaine and Helena make! Or maybe it’s a circle, with a littler circle on top: All the energy flows one way, to get caught up in that nonfeedback loop which is Helena’s self-regard. Booth loves Blaine—Blaine loves Helena—Helena loves Helena, and loves Helena, and loves Helena. Plus there are arrows in the diagram. Blaine does need Booth, as an amusing and adoring and sometimes useful lapdog. Helena does need “Ruthie,” as that new toy or pet she’s always looking for.

Okay, yeah, we’re getting some psychosexual complexity here! And we’re keeping the antiquarian-academic-tome reading narrator of whom both M. R. James and Lovecraft were so fond, as well as M. R.’s nuance a bit expanded (the ritual) and H. P.’s dread of a cosmos neither rational nor sane.

I catch further H.P.-echoes in Helena’s predatory fixation on Blaine (Asenath) and her remarkable hair (Marceline). Interesting that the “weak” friend is not the “vampire’s” target. On one hand, Blaine was the more challenging conquest, hence desirable. On the other hand, Booth was so unreachable for Helen that captivating him would have been the shiniest trophy on her shelf. Booth’s sexual preferences aside, he sees right through that changeling-demon-hussy! Or he thinks he does. His love for self-centered Blaine suggests that his jerk-detection system may not be as accurate as he’d like to think.

There’s also evidence that all his jerk-detection system needs is an infatuation filter. Blaine may have dazzled Booth, but Booth does resent his friend calling him “Boothie”; silly enough if used privately, but Blaine calls him that in front of others, as if “to reassure his friends that he had more savoir-faire than to treat me as an equal.” Ow! I wonder if Helena is mimicking Blaine in his belittling style of pet-naming—look how she tosses off not only Boothie but also Auggie and Ruthie.

More telling still is Booth’s resentment that Blaine could persuade him to anything, even sacrificing his own blood to resurrect Helena. A “hard, angry little voice” in his head tells him Blaine deserved to die if he couldn’t bleed for his wife. And that voice is like Helena’s!

The relationship diagram gets yet more complicated, with an arrow linking Booth and Helena. Maybe he doesn’t hate her with a pure and simple hate. Maybe he envies her power to influence others, her power to attract, powers she possesses to an even greater extent than Blaine. Maybe he loves her a little for that.

Whoa. Complexity upon complexity. What if Helena’s doing Booth a favor when she suggests him bringing Blaine back. She must figure he’d think of that himself. She must know his inclination to reject any advice she gave.

His hatred of her saves him from the Blaine voice in his head, that tries to persuade him to do the ritual again just as it persuaded him to give his blood for Helena. His blood. Which re-embodies Helena. Another connection between the jealous friend and the wife.

Henry James begins to look with respect at our little psycho-diagram.

One more question: Where’s the Samuel Mather Parrington Museum? Far as I can tell, Monette hasn’t disclosed the location. She hails from Tennessee, but I like to think that with a middle name like Mather, old Samuel may have built his museum not so very far from Boston’s Copp’s Hill Cemetery and the modest little crypt that houses the remains of Increase and Cotton. Some potent graveyard dirt there, I bet, and well-aerated by ghoul burrows.

Next week, strange maladies are diagnosed in J. Sheridan LeFanu’s “Green Tea.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.