Is there any situation more fraught, more plagued by potential communication traps, than exchanging gifts?

Gift giving is hard enough between two humans—choosing the perfect present, accepting your own graciously, agonizing over the relative equal value of the items exchanged—that even contemplating performing this ancient, charged act of communication with an alien species boggles the mind. And yet, more and more alien narratives concern this exact scenario; it’s no longer a question of if we will meet alien life, but how we will handle the exchange of ideas and potential tools when we do. Forget first contact—it’s first trade, and it may determine the fate of the entire human race. Especially because rarely does an interspecies gift exchange occur without major ramifications.

Spoilers for Arrival (and “Story of Your Life”), The Sparrow, The Message podcast, and Interstellar.

The ending of Arrival—and “Story of Your Life,” Ted Chiang’s novella that inspired the movie—is presented as strangely hopeful: While deciphering the alien language Heptapod B, which shares absolutely nothing in common with any human tongue, linguist Dr. Louise Banks discovers that she will fall in love with physicist Ian (Greg in “Story”) Donnelly, and that they will have a spirited daughter who they will both outlive. As her future and their daughter’s short life is laid out before her, every future moment as sharp as a treasured memory, Louise makes the decision—knowing all of the joy, and then the pain, of Ian leaving and their child dying—to still fall in love with him and conceive her. It’s one of humans’ favorite adages: better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all, right?

This is devastating.

If you put aside the swelling soundtrack and the layered scenes of Louise hugging Ian for both the first time ever and for what feels like the first time in years, we watch someone confront her lack of autonomy without question. We witness her choice to set into motion her and Ian’s romance without warning him of the heartbreak that will follow, without giving him a chance to flee, because it has already happened. She asks him, “If you could see your whole life laid out in front of you, would you change things?”, but he brushes it off as a hypothetical, never imagining that years later she will confess the truth to him, when it’s too late to save their daughter from her rare illness. He will leave both of them. Louise embraces this reality, this responsibility, and him, all at once.

When new cultures meet, it is customary for them to exchange items as a sign of good will—to do the opposite, to withhold information or aid, would make them combatants. But without a complete understanding of each other’s language or cultural values, these gifts do not always have their intended effect. Chiang’s “Story of Your Life” sees the humans participate in eight gift exchanges with the heptapods, in which each side presents a gift independent of the other. Louise recalls the final exchange, in which her side does the equivalent of shaking a wrapped Christmas present trying to decide if its contents are worthwhile:

This was the second “gift exchange” I had been present for, the eighth overall, and I knew it would be the last. The looking-glass tent was crowded with people; Burghart from Ft. Worth was here, as were Gary and a nuclear physicist, assorted biologists, anthropologists, military brass, and diplomats. Thankfully they had set up an air conditioner to cool the place off. We would review the tapes of the images later to figure out just what the heptapods’ “gift” was. Our own “gift” was a presentation of the Lascaux cave paintings.

We all crowded around the heptapods’ second screen, trying to glean some idea of the images’ content as they went by. “Preliminary assessment?” asked Colonel Weber.

“It’s not a return,” said Burghart. In a previous exchange, the heptapods had given us information about ourselves that we had previously told them. This had infuriated the State Department, but we had no reason to think of it as an insult: it probably indicated that trade value didn’t really play a role in these exchanges. It didn’t exclude the possibility that the heptapods might yet offer us a space drive, or cold fusion, or some other wish-fulfilling miracle.

In Arrival, the gift-giving is one-sided, or so it seems from the start. (And that’s even more awkward, the idea of someone handing you a present and you getting caught with nothing to give in return.) Louise and Ian can’t make sense of the heptapods’ semagram meaning “offer weapon”; Colonel Weber and the other top-secret agents demand to know why the aliens are offering weapons, even as Louise points out that weapon could just as easily mean tool for them.

But of course the humans assume that weapon means weapon. Their ancestors are the ones who “gifted” Native Americans with smallpox-ridden blankets for the first Thanksgiving.

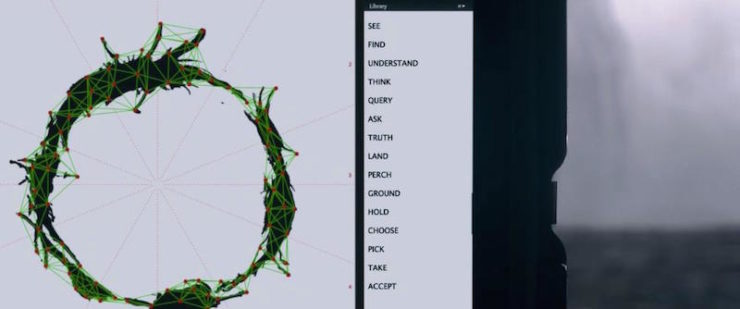

By the end of the film, Louise and we learn that weapon does indeed mean tool, and “offer weapon” is one word instead of two, a definition rather than a term—”offer-tool” = gift. And that gift is Heptapod B.

Perhaps it’s the defensive paranoia that clouds everyone else to cracking this puzzle, or the fact that it wasn’t a traditional gift exchange without the humans offering something in return. But when Louise goes into the ship to talk directly to their heptapod visitors (nicknamed Abbott and Costello), she discovers that humans are expected to return the favor—just in three thousand years, and in a way that the heptapods don’t specify but that is linked with Louise translating Heptapod B and publishing a book with her findings, so that all people who want to become fluent can.

Yes, the heptapods have an ulterior motive, but it won’t play out for several millennia; and in the meantime, it elevates the humans to an entirely new plane of consciousness, one that makes that three thousand years feel much closer than it would otherwise. Whereas Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar never tells us how “we” become the “they” who put the entire plot into effect, Arrival pinpoints that exact moment. And again, it’s for the humans’ benefit—a recurring theme in alien gifts, the underpinning belief that they are helping us.

Perhaps the most horrifying example of this misguided gift-giving comes in Mary Doria Russell’s 1996 novel The Sparrow, about a Jesuit-funded crew who land on the distant planet of Rakhat, drawn by the beautiful, strange songs they pick up across light-years. It’s not the Runa and Jana’ata’s language Ruanja that leads to the mission’s tragic undoing, not exactly: While polyglot priest Emilio Sandoz attains fluency in the language within a few years, knowing the names for organisms and rituals does nothing to prevent his blind spots with regard to Runa and Jana’ata culture. The first mistake belongs the humans: Having exhausted their ship’s food stores, they set up gardens on Rakhat and teach the peaceful, herbivore Runa the concept of agriculture. Such a seemingly ordinary action backfires when the Runa, no longer required to forage for food, experience a baby boom—forcing the carnivorous Jana’ata to harvest the babies, as they must keep their prey (yes, their prey) at a certain population.

The ensuing massacre leaves only Emilio and one other crew member alive, under the protection of Jana’ata merchant Supaari VaGayjur. But the only way for Supaari to protect them, he explains, is to make them hasta’akala. He gestures at the delicate sta’aka ivy plant as he speaks, but Emilio believes that he is simply pointing out a beautiful piece of greenery. It is only when the muscles of his hands are being stripped away that Emilio realizes that the sta’aka, growing on a stronger tree, represents a dependent—and that by making his hands resemble the flowing ivy, he has become Supaari’s dependent. Here’s the kicker: The hasta’akala is an honor, a gesture by Supaari to show that he can afford to pay for the wellbeing of the humans who rely on him. Instead, Emilio is maimed and driven half-mad by pain and terror.

In both cases, each side thought that something that benefited them would be equally good for the other.

But while Emilio was at least offered choices, even if he didn’t understand their context at the time, Louise cannot do anything but accept Heptapod B, due to its contagious nature: As soon as she becomes proficient in the language, not only does she begin thinking and dreaming in it—as is often the case with human languages—but it also begins rewiring her brain even before she realizes what has taken place. Once she achieves simultaneous consciousness, seeing every beat of both her life and that of her daughter laid out all at once, there is no way she can return to sequential consciousness.

The heptapods don’t ask for humans’ consent to this entire transformation of their sense of self, nor do they warn them; there is no semagram for “side effects.” Perhaps because for the heptapods, this is the ideal mode of existence, a natural evolution for a lesser race. That seems to be the same M.O. behind the extraterrestrials in The Message, the popular sci-fi podcast written by Mac Rogers and produced by Panoply and GE Podcast Theater. The eight-episode series is presented as a podcast called The Message, hosted by Nicky Tomalin, documenting a team of cryptographers’ attempts to decode the mysterious Transmission 7-21-45—think Serial meets Contact.

Like the Ruanja songs from Rakhat, the transmission—nicknamed “The Message”—meets SETI’s requirements for proof of extraterrestrial life: repetition, spectral width, extrasolar origin, metadata, and Terran elimination. But while the Jesuit crew preps their mission in a matter of months, The Message remains unsolved 70 years after its first transmission on July 21, 1945. As the team at encryption think tank the Cypher Group delve into this bizarre, otherworldly missive, The Message proves itself to be even more contagious than Heptapod B: Every person who listens to it eventually contracts a mysterious, seemingly fatal respiratory illness with no cure… and Nicky has already published podcast installments transmitting The Message to her listeners.

Even after they take down those episodes, The Message continues to pass from person to person, and those who are already sick rapidly worsen. Because here’s the thing: The Message can only be decoded by those who are near death, as their brains are rewired and their consciousnesses expanded to receive the actual message intended for humans 70 years ago, when we unlocked nuclear power. And now, the aliens want to help us access a new form of technology. But, just as the weapon/tool dichotomy, this technology has the double-edged potential for healing or harm. It’s up to us to decide what to do with it.

Usually when one considers cost with regards to gift-giving, it’s a question of how much the giver will spend on the recipient. In these cases, it is the recipient—the humans—who must bear the cost. Emilio loses everyone he loves and his own autonomy, down to the use of his hands. The cryptographers watch their colleagues and friends die before they solve the mystery behind The Message. And Louise gains the knowledge that for all of her joy with Ian and their daughter, someday she will lose them both.

But does Louise also lose her free will? This was one of the biggest questions weighing on my mind after watching Arrival, as I kept trying to think of hypothetical scenarios in which Louise could change the course of her life, and the paradoxes such actions might create, à la Back to the Future. The movie doesn’t delve into this, as it ends on Louise’s realization of her simultaneous consciousness; but “Story of Your Life” uses a seemingly mundane example to present the case for why Louise both does and doesn’t have agency:

We walked past the section of kitchen utensils. My gaze wandered over the shelves—peppermills, garlic presses, salad tongs—and stopped on a wooden salad bowl.

When you are three, you’ll pull a dishtowel off the kitchen counter and bring that salad bowl down on top of you. I’ll make a grab for it, but I’ll miss. The edge of the bowl will leave you with a cut, on the upper edge of your forehead, that will require a single stitch. Your father and I will hold you, sobbing and stained with Caesar dressing, as we wait in the emergency room for hours.

I reached out and took the bowl from the shelf. The motion didn’t feel like something I was forced to do. Instead it seemed just as urgent as my rushing to catch the bowl when it falls on you: an instinct that I felt right in following.

“I could use a salad bowl like this.”

The novella concludes with Louise’s explanation that her agency is now tied up in making sure that the future she saw come to pass:

The heptapods are neither free nor bound as we understand those concepts; they don’t act according to their will, nor are they helpless automatons. What distinguishes the heptapods’ modes of awareness is not just that their actions coincide with history’s events; it is also that their motives coincide with history’s purposes. They act to create the future, to enact chronology.

Freedom isn’t an illusion; it’s perfectly real in the context of sequential consciousness. Within the context of simultaneous consciousness, freedom is not meaningful, but neither is coercion; it’s simply a different context, no more or less valid than the other. It’s like that famous optical illusion, the drawing of either an elegant young woman, face turned away from the viewer, or a wart-nosed crone, chin tucked down on her chest. There’s no “correct” interpretation; both are equally valid. But you can’t see both at the same time.

Similarly, knowledge of the future is incompatible with free will. What made it possible for me to exercise freedom of choice also made it impossible for me to know the future. Conversely, now that I know the future, I would never act contrary to that future, including telling others what I know: those who know the future don’t talk about it. Those who’ve read The Book of Ages never admit to it.

Humans are no longer in control of determining what their destiny is, but rather determining that that destiny exists.

Being the recipient of a gift is much trickier than being the gift-giver, as it places a number of societal burdens on you. You can’t regift it—at least, not until enough time has elapsed that the gift-giver doesn’t know you rejected their present—so you make the best of the gift you’re given.

Natalie Zutter is going to look at holiday gift shopping so differently this year. Read more of her work on Twitter and elsewhere.