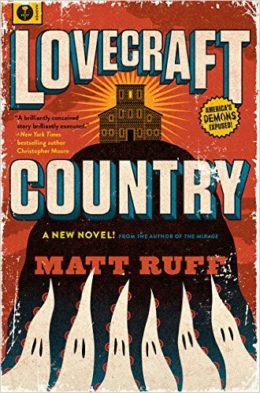

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn. Today we’re looking at Matt Ruff’s “Lovecraft Country,” first published in his Lovecraft Country novel/fix-up in February 2016. Spoilers ahead.

“I don’t get mad. Not at stories. They do disappoint me sometimes.” He looked at the shelves. “Sometimes, they stab me in the heart.”

Summary

Atticus Turner, recently discharged from serving in the Korean War, receives a letter from his estranged father: Come home. Montrose Turner has discovered something about his dead wife’s long-mysterious ancestry, and they need to go to Arkham, Massachusetts, to look into it.

Atticus has loved SFF since childhood, in spite of (or perhaps partly because of) Montrose’s contempt for this “white man’s” genre. Montrose gloried in pointing out the racism in authors like Edgar Rice Burroughs; his biggest triumph was to present newly Lovecraft-smitten Atticus with one of Howard’s particularly vile poems.

Uncle George Berry, however, is a fellow fan. He runs the Safe Negro Travel Company and publishes a guide for black travelers in all the states, Jim Crow or supposedly otherwise. Atticus takes this book along on his trip from Jacksonville, FL, to Chicago, but still has trouble with suspicious police and surly auto mechanics. He’s glad to reach his South Side neighborhood intact.

His first stop is George’s apartment, to ask what’s with Montrose asking Atticus to accompany him to Lovecraft’s fictional town? George reads Montrose’s letter and says Atticus misread his father’s handwriting—“Arkham” is actually “Ardham,” a real Massachusetts town. The atlas shows it as a tiny hamlet near the New Hampshire border. Too bad it’s in Devon County, a regressive backwater where blacks have had nasty run-ins with locals, especially Sheriff Hunt of Bideford.

Atticus goes next to his father’s apartment, but finds Montrose a week gone—oddly, he left with a young white stranger driving a silver Daimler. A note tells Atticus to follow Montrose—to Ardham.

George decides to come along. He loads his old Packard with necessities for travel through uncertain territory. At the last minute Atticus’s childhood friend Letitia Dandridge joins the party. It’s a free ride to her brother’s in Springfield, MA, but she’s also convinced that Jesus wants her to go as a sort of guardian angel to George and Atticus. She soon proves her worth by helping the two escape from a diner stop turned ugly. A silver Daimler comes out of nowhere to assist in the rescue, apparently using magical force to wreck the trio’s pursuers.

Against her (and Jesus’s) wills, Atticus and George leave Letitia behind in Springfield, or so they think. They hope to sneak through Bideford to Ardham in the dead of night, but Sheriff Hunt and deputies ambush them. They march Atticus and George into the woods at shotgun point. Luckily Letitia’s stowed away in the back of the Packard. She sets Hunt’s patrol car on fire, drawing him and one deputy back to the road. The one left to guard Atticus and George vanishes suddenly, snatched by something unseen that lumbers through the woods with such heft it fells a tree. Atticus and George hightail it back to the Packard, where Letitia’s already knocked out a deputy with her gas can. Atticus knocks out Hunt, and the three race on to Ardham.

A stone bridge crosses the Shadowbrook into a weirdly feudal land: fields and village peopled by deferential white “serfs,” manor house looming on the hill above. A silver Daimler’s parked before it. The majordomo, William, welcomes Atticus and friends. They’re expected. As for the Daimler, it belongs to Samuel Braithwhite, the owner of Ardham Lodge and a descendent of Titus Braithwhite, the “natural philosopher” (not sorcerer) who founded Ardham. Atticus recognizes the name: Titus owned Atticus’s great-great-great-grandmother, who escaped during a fiery cataclysm at the original mansion. Evidently the child she later bore was Titus’s; hence Atticus is also Titus’s descendent, entitled to a place at the Lodge. The other members will arrive soon.

In his room, Atticus discovers a book of regulations for the Adamite Order of the Ancient Dawn, evidently Braithwhite’s cult. A search for Montrose (supposedly gone with Braithwhite to Boston) is fruitless. The Adamites, all white men, gather for dinner. To their dismay, Atticus and friends are elevated as special guests—indeed, Atticus tries out one of the regulations and finds that as Titus’s descendent, he can successfully order the disgruntled lodge members to leave. But one young man seems more amused than dismayed. He turns out to be Samuel’s son, Caleb, and the driver of the Daimler.

Caleb takes Atticus to meet Samuel, who treats him with disdain despite their relationship. Atticus will be necessary for a certain ritual on the morrow; meanwhile, he may go see Montrose, who’s imprisoned in the village.

Montrose claims he didn’t want Atticus to come to Ardham, but his “abductor” Caleb somehow spelled him into leaving that note. When Atticus, George and Letitia try to rescue Montrose and clear out of town, Caleb uses magic to stop them. He incapacitates Montrose to force Atticus to cooperate in the ritual. The next morning Caleb leaves Ardham, claiming he’s sorry for his distant cousin’s predicament.

The ritual—intended to help the Adamites reclaim their “rightful” power—takes place in the manor house. Atticus is stationed between a silver-knobbed door and a crystal-capped cylinder. He’s to be a conduit between the cylinder-collector and whatever energy comes through the door. Braithwhite’s magic enables Atticus to read an invocation in “the language of Adam.” The door begins to open, letting in “the first light of creation.” Channeling it will destroy Atticus’s identity, but he prefers being himself. He takes a bit of paper from his sleeve, which Caleb slipped him with his breakfast. When he reads the Adam-language words on it, a veil of darkness drops over him and protects him from that first light of creation. Braithwhite and the cultists, without their human circuit breaker, aren’t so lucky.

Caleb Braithwhite, it seems, has staged a coup. For their part in it, Atticus and friends are permitted to leave Ardham, taking with them thank-you gifts including a spell of “immunity” on George’s Packard, which will render it invisible to unfriendly eyes, police or otherwise.

As they leave Devon County, Atticus tries to believe the country they now travel to will be different from the one they leave behind.

What’s Cyclopean: “Lovecraft Country” gets more effect from direct language than from purple adjectives.

The Degenerate Dutch: Lovecraft’s racism is in the spotlight, synecdoche for the racism of many, many men of their times.

Mythos Making: The meta is thick on the ground: Ardham and the Shadowbrook River another layer on the map of Imaginary Massachusetts, atop Arkham and the Miskatonic. Having read the originals, Atticus and family are thoroughly genre-savvy.

Libronomicon: Funny how that copy of the Adamite rules ends up on Atticus’s guest shelf, hidden among a stack of pulp genre fiction.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Decades before the story takes place, one Ardhamite villager survives the Order’s first epic ritual fail. He ends up in an asylum, where he leaves precisely the sort of gibbering diary any occult researcher would be delighted to find.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

It’s been suggested that dystopia is when the nasty things that happen to minorities start happening to everyone.* This week’s story, along with the larger collection of which it’s a part, suggests that cosmic horror is when those nasty things are embedded in the fabric of the universe itself. Lovecraft’s narrators are forced to confront an uncaring cosmos where the rules are stacked against them, their lives are given little value, and the wrong move (or sometimes even the right one) can get them killed or worse.

For his Anglo witnesses, that epiphany upends their entire worldview—often, the horror is explicitly that cosmic truths kick their own civilization out of the spotlight. That’s how Titus Braithwhite saw the universe: “I can only imagine his horror today, after a hundred and eighty years of the common man.” But it takes rare privilege to start a story believing in an orderly universe with you at the center. For the Turners, a hostile and uncaring cosmos comes as little surprise. That gives them the perspective to survive, and even resist.

That’s not the only Mythosian trope that Ruff puts in a blender. Lovecraft transmuted his fears, including of other humans, to terrors that even the more tolerant can understand. Ruff pulls off the same trick in reverse, making the horrors of human prejudice part and parcel of the cosmic dangers. Atticus learns terrible secrets about his ancestry—but rather than being descended from Salem’s elder-god-worshipping witches, or scary South Pacific aquatic humanoids, he’s stuck with white supremacist witch-hunting natural philosophers. Squick! Not to mention their preference for putting human shields between themselves and Things Man Was Not Meant to Know.

The Adamite Order reminds me rather a lot of Joseph Curwen and his circle of immortality-seeking necromancers. They seem like they’d get along, if they weren’t arguing terminology or trying to kill each other. They certainly have a similar fondness for using (and sacrificing) their descendants. Later stories continue the thread of Caleb Braithwhite’s demibenevolent intervention into the Turners’ lives. They all play with weird fiction tropes, ranging from creepy old houses to body-snatching and the dangers of uncontrolled interplanetary travel. What differs from the usual run of weird fiction is the perspective—and therefore the reactions.

One trope that struck me particularly, this read, was the Standard Horror Movie Town. You know the one—it’s easy to get there, hard to leave with all your limbs intact, and populated by worrisomely coordinated and insular natives. It hadn’t occurred to me before, but this is yet another horror that’s often been all too mundanely real. Sundown towns, but with vampires instead of white people.

“Lovecraft Country” is grounded in Atticus’s family’s research for The Safe Negro Travel Guide. The Guide is fictional, but based on real books that really did help African Americans navigate the hazards of segregation. It’s a good conceit for the stories, requiring exploration past known safe boundaries—much as wizardry does. It also gives me instant empathy with the characters. Until Obergefell v. Hodges gave us the full protection of federal law, my wife and I kept a careful map in our heads of what rights we lost as we crossed state lines. No hospital visitation rights in Florida. Shared insurance illegal in Michigan. Merchants able to refuse us service all over the place. And for all that, we had it easier than Atticus: If the hotel clerk mistakes you for sisters, you can always nod and ask for two full beds.

Still, a hostile and uncaring universe is a bit less startling to me than to Professor Peaslee, too.

*If anyone can find the original quote for me, I’ll happily add the citation. Alas, my Google-fu fails. The results of a search for “dystopia white people” are… mixed. Thanks to Tygervolant for tracking it down: “Dystopian novels are when what happens to minorities starts happening to Whites.” — JL Sigman

Anne’s Commentary

I’m going to need some time to assimilate this week’s story, which I found like a megarollercoaster ride. A megarollercoaster ride, that is, if the megarollercoaster paused between exhilarating climbs and gut-wrenching twists and terrifying freefalls to let the riders ponder their experience. Which “Lovecraft Country” does, fortunately, and its quiet stretches are peopled with characters with whom I much enjoyed chewing over the situation.

The worst part of the trip was when I took a side excursion to the Lovecraft poem Montrose digs up for the edification of his son. Yes, it’s a real Lovecraft poem, dated 1912, perhaps meant to be humorous in its drop from high-flown language about the Olympian gods to that pejorative that caps its “punchline.” See, the Olympians made man in the image of Jove. Then they made animals for lesser purposes. Hmm, wait. Aren’t we leaving too much “evolutionary” space between man and beasts? Yeah, so let’s make an intermediate creation, a beast in the rough shape of a man but full of vices… and you can probably guess where that one’s going. Because Jove is obviously white, or at most bronzed from all the celestial radiance under which He basks.

You can read the poem at the link above, if you want (along with Nnedi Okorafor’s more thoughtful commentary). I wish, like Atticus Turner, that I’d missed it, so I could enjoy “At the Mountains of Madness” without having seen its author in his ugliest literary skivvies.

I don’t know about Montrose, though. I’m going to have to consider him longer before I can forgive him for his radical approach to child-rearing. And to wife-nagging as well. Or is he right to reject Lovecraft’s notion of things-better-not-explored? Is that moral courage?

Yeah, I have to think about it longer. For now I’m more impressed by George’s approach to defiance (gonna go where I want no matter what barriers you try to put in my way); and Letitia’s dual genius for survival and fun; and Atticus’s fierce sense of self, which won’t submit to annihilation however “sublime.”

At first I found the switch from the realistic opening to over-the-toppish and violent road adventure a little disconcerting. Then I started making a connection between the “pulpier” parts of George and Atticus’s libraries and the action at hand. As Atticus’s cousin Horace turns white-dominated space cadet stories into black-populated comics, Ruff seems to be reversing the pulp formula from bold white explorers venturing into dangerous dark-peopled lands to bold black explorers motoring through segregated towns. And those white natives are restless, for sure, except they wield fire axes and shotguns instead of spears, flashlights and spotlights instead of torches. Also like the pulps, the moral-racial dichotomy is relentless. The blacks are all good, even those like Letitia who are a bit shady around the edges. The whites are all crude and bad and savage.

Except for Caleb Braithwhite, but see, he’s the magical negro, not Atticus. Or the magical Caucasian, I guess. He’s the one who guides Montrose, hence Atticus, to Ardham. He’s the one who saves Atticus and crew from the firetruck of doom. He’s the one who figures out a way to control Atticus without actually killing or maiming Montrose or George or Letitia. And he’s the one who gives Atticus the key to conquering the Sons of Adam—and to saving himself, as the living Atticus rather than the nameless primal possibility. He gives wise advice. He’s the most powerful of the Adamite “natural philosophers,” hence truly magical.

Caleb doesn’t sacrifice himself for the black characters, though. In fact, through them, he promotes himself. An interesting twist to the trope. And is he done being useful to, and using, our heroes? I’ll have to read on to find out, and I will read on, that’s certain.

I’ll also have to read on to see how deep into true Lovecraft country the book travels. So far Ruff creates his own kingdom of darkness on the Massachusetts map: the fictional county of Devon, the fictional townships of Ardham (NOT Arkham) and Bideford, the woods haunted by something more than black bears. Something a lot bigger, a lot eldritchier. A shiggoth/shoggoth? The opposite of that first light of creation the Adamites wanted Atticus to corral for them, to tame down for domestic use? And what would that be, the last dark of destruction?

I have more digesting to do. Right now the scariest part of Ardham remains (as Atticus wishes he needn’t believe) what lies outside it.

Next week, for a change of pace, we switch from the malevolence of humans to that of porpoises in James Wade’s “The Deep Ones.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with its sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with its sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.