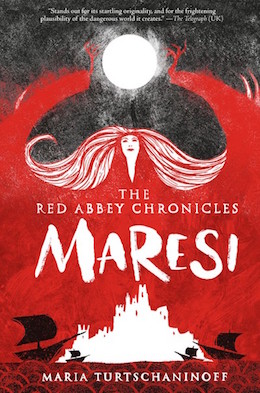

Maresi by Maria Turtschaninoff is a first-person young adult novel, presented as a record written by the titular character. When Jai, a young woman fleeing her father, arrives at the Red Abbey for shelter, she brings on her heels the danger of the outside world. The abbey is a female-only space filled with learning, home and hearth; it exists to protect and preserve women’s rights and rites. Maresi must discover, through trial and danger, who she is and what path she is called to serve—and protect her home in the process.

The novel (which is first in a series) won the highest honor for young adult fiction in Finland, the Finlandia Junior Award, in 2014. Since then, the Red Abbey Chronicles have been translated across the globe—in Chinese, German, French, and more. Amulet Press has picked them up for publication in the US beginning in early 2017.

Maresi reads as an intentional throwback to the earlier works of Ursula K. Le Guin and Marion Zimmer Bradley. It’s a feminist tale in a tradition of feminist tales focusing on the concerns of the second wave: the power of women as women and of reclaiming female spaces, a separatist approach that lauds ecological conservation, inter-generational mentorship, equal division of labor, and the mystical properties of the female body when it is venerated. Turtschaninoff also has a specific concern with valorizing women’s work, femininity, and gentleness as pure and good—in no sense lesser than masculine pursuits. However, the girls and women of the Red Abbey also do hard physical labor and have steel spines; there is softness, here, but it is not softness without courage and strength.

The plot is simple and fast—this book took me barely a few hours to finish. Jai arrives at the island, begins to bond with Maresi and open up about herself, and then a ship of men appears on the horizon: her father’s soldiers, come to search for her. The women of the abbey use their magic to destroy the ship in a storm, but a second ship comes, bearing the man himself and his mercenaries. The abbey is besieged. Each of the women uses her skills, wits, and strength to survive and protect Jai—who ultimately murders her father—and Maresi, who uses her calling to the Crone to utterly destroy the mercenaries in turn. It’s very direct, but quite compelling nonetheless.

The relationships between the girls—the focal point of the novel, really—are familial, supportive, and complex. Though I’d have selfishly appreciated a bit of queerness somewhere in here, it is also nice to read a young adult book without even the slightest hint of a romance. Maresi and Jai form a close and intense emotional bond that sustains them—and it does not require romance to be the most important thing either girl has. It isn’t a possessive love, but it is a powerful one. The pair of them grow together: Jai as she recovers from her nightmarish upbringing, Maresi as she tries to find her path in life. The scenes of them reading together in silence are some of the most delightful things in the novel for their pure pleasantness.

However, I can’t avoid noting that there is a complex problem that detracted from the pleasure I otherwise took in this novel. It’s the problem a contemporary reader usually encounters in texts from the mid-seventies: it’s feminist, and handsomely so, but that feminism appears uncomfortably essentialist in its approach to gender (or, to be more accurate to the novel’s approach, sex). I understand the difficulties in balancing a necessary and healing embrace of the bodies that are typically labelled, judged, and abused based on their femaleness with a contemporary understanding that biological essentialism is a flawed and patriarchal framework—but it is also important. It would take little more than a single line of acknowledgement in the text to solve this conundrum: that women of all kinds are welcome. Particularly in a world where the trifold magic of maiden/mother/crone is so real and true, it seems hard to believe that the magic of the island wouldn’t recognize a girl in need based on the flesh she was born with.

Perhaps this is an issue of translation, as I’m unable to read the text in its original Finnish. It seems a shame, too, for a book that has so much I found compelling and thoughtful—and more so since there are vanishingly few openly, inspirationally feminist texts for young readers. Given that, and given the fantastic work the text does do, I’d still recommend it. But I’d also note that it might be a less pleasant read, for that elision and the implications it creates given recent feminist history, for women who are uncomfortable with essentialist approaches to their gender. A contemporary take on second wave fiction needs to be responsible in terms of the things it borrows and the things it critiques; as a huge fan of Joanna Russ, I understand the difficulty inherent in that project, but also think it is ethically necessary.

Still: though Maresi fails to critique or reinterpret some of the glaring issues of those second wave feminist novels, it also succeeds wildly with capturing the strength of their spirit and ethos. That it does so unflinching for a young adult audience, in a world like the world we are currently living in, deserves kudos and attention. I’m unwilling to discard such a significant project due to its failure to check all the boxes, so to speak.

Because, make no mistake, there is something breathtaking about the scene where the women of the abbey bind and then unbind their hair to call down wild storm magic with their combs, their songs, their togetherness. There is something quiet and terrible about the Rose offering herself as the Goddess embodied to the men who have invaded their island, to ensure the safety and protection of the other women who would have been brutalized. The novel does not shy from issues of rape, abuse, and recovery; while Maresi came to the abbey due to the poverty of her loving family, Jai has escaped a father who murdered her younger sister and would have murdered her and her mother both eventually. She is not the only girl who bears scars from her time before becoming a novice.

Again: I very much appreciate that, though this is a book for young adults, it refuses to ignore the violence that women endure in patriarchy—because young women already know that violence, and it deserves to be spoken about. This novel refuses to ignore the truth. It is sometimes horrible, but it is honest, and we, like Maresi, bear witness. Maresi also acts to protect her loved ones and her island. She, in the end, embraces the call of the Crone and slaughters the men who would hurt the youngest of their girls. She doesn’t do it out of anger or revenge, but of desire to protect, to be worthy of the girls’ trust.

I’m curious about where the further novels in this series will go, and what they’ll focus on. As for this one, I’m glad it exists; the feminist fiction of the seventies and early eighties was a boon and an act of artistic war, and I’m glad to see that spirit continue. Do not go quietly—and don’t stop fighting for each other, to better the world we all share. I think that’s a message we could all use, really.

Maresi is available now from Amulet Books.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.