The Wild Cards universe has been thrilling readers for over 25 years.

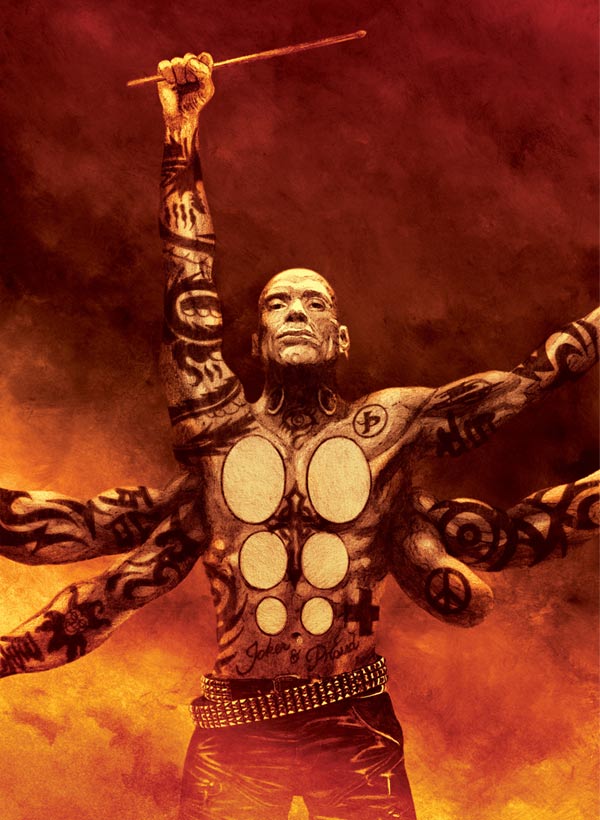

One act of terrorism changes the life of Michael “Drummer Boy” Vogali forever in Stephen Leigh’s “The Atonement Tango.” Now without his band, Joker Plague, Michael must figure out a way to re-build his life–and seek revenge.

Michael—aka “Drummer Boy,” aka DB, as most of the people who knew him called him—saw Bottom peering out through the rear curtains of the stage where their band, Joker Plague, was set up to play to the audience in Roosevelt Park. Through the thick velvet, they could hear people clapping and shouting impatiently. “Well?” Michael asked as Bottom let the curtains close.

Bottom glanced back at him: the head of donkey on a man’s body. The thick lips curled over cartoon-character teeth; he held the neck of the Fender Precision already strapped around his neck. Michael twirled the drumsticks held in each of his six hands. “It’s a decent crowd,” Bottom told him. “Nearly all jokers, of course.”

“A ‘decent’ crowd? You mean a mediocre one. Shit.” Michael pulled one of the curtains aside, looking out himself. The front of the stage area was packed, the audience there applauding in unison and pumping fists in the air, but the crowd thinned out well before it reached the end of the park’s field. When Joker Plague had played here during their heyday ten years ago, the crowd would have spilled out onto Chrystie and Forsyth Streets, which the Fort Freak cops would have closed off.

But that was years ago. The Joker Plague faithful were here, but…

They were rapidly becoming an ‘old’ band. While they could still pack the smaller venues, in the past they had played huge arenas to thousands—not just to jokers, but to crowds of nats as well. They still had fans, still put out the requisite new album every year or two, but their new material never got the airplay, coverage, and good reviews that their old stuff had, and the nats now paid no attention to them at all.

Playing music had been his refuge when everything in his life had turned to shit. Now he was losing that too. Even the jokers’ rights events where he’d once been so visible had mostly vanished, just like Joker Plague’s fame and days with the Committee. He was becoming “that old guy, whatshisname” that they dragged out on stage to give a few lines before the “real” talent appeared.

Washed-up and useless in his mid-thirties. Playing a parody of himself now. “Fuck.” Michael let the curtain close.

“What’s the problem?” Shivers asked. He was the guitarist for the group, who had the appearance of a bloody devil newly released from hell. Everything about him was the color of blood: his skin, his face, his hair, the twin horns jutting from his forehead, his trademark Gibson SG guitar. Shivers, like the other members of the group, didn’t seem to notice or care how they’d fallen. If they were no longer making the money they used to, money managed to come in and it was sufficient. “It’s showtime.”

S’Live—a balloon-like face gashed with mouth and eyes, thin and impossibly long arms protruding from his head like a living Mr. Potato Head—hovered in the air behind Shivers. The Voice, the lead singer for the group, was there as well: invisible but for the wireless mic that floated in the air near Shivers without any apparent hand holding it there. Their head roadie, a joker built like a two-legged, seven-foot-tall pit bull (and with the same breath), gave them a double thumbs-up at Shivers’ statement.

“Shiver’s right,” the Voice said in his mellifluous, rich baritone. “Let’s get on with it. There’s a couple chicks waiting for me back in the hotel room, getting themselves ready, if you know what I mean.” He laughed. The Voice lifted the mic, flipping the switch on the barrel. “Are you ready?” he bellowed, his voice amplified to a roar through the PA system, the echo from the nearest buildings bouncing back to them belatedly. A mass cry from the audience answered him. “C’mon,” the Voice responded. “You can do better than that! I said, are you ready?”

This time the response could be felt through the risers of the stage, throbbing with the affirmation. The microphone bobbed through the air to the curtains, and the Voice’s invisible hand held them open.

Michael clicked on the switch for his wireless throat mics and went through, tapping with his drumsticks on the rings of tympanic membranes that covered his bare, muscular chest, all six arms moving. From the openings on either side of his thick neck, the sound came out from the two throat “mouths” to be caught by the mics there: a throbbing, compelling drum beat, the lowest bass ring pounding a steady, driving rhythm through the subs of the PA system.

The crowd erupted as a spotlight found Michael and the stage lights began to throb in time with his drum beat. Then Shivers came through with a single, killer power chord that screamed from the Marshall amps at the back of the stage. S’Live glided through the air to his bank of keyboards, and Bottom strode to the other side of the stage, thumb-slapping his bass in a funk pattern to complement Michael’s beat, his ass’s head bobbing.

They let the song develop and grow in volume as fog machines began to throw out mist colored by the stage lighting, through which there was sudden movement: the Voice stepping forward to the front of the stage, visible only as an emptiness within the fog. His powerful vocals throbbed from the speakers as he began to sing “Lamentation,” the title song from their latest album:

Rivers etch the stones and die in sand

Spires carved by unknown hands cannot stand

A storm cloud stalks the sky alone and emptied

From a place where nothing goes and nothing ever comes

Even as the group kicked hard into the chorus of the tune, Michael could feel the dissatisfaction of the audience. Increasingly over the years, their audiences had only wanted to hear the old hits from their first three or four albums. They seemed to tolerate the new tunes, but the crowd only screamed their approval when they played the old stuff. The walls of the sound system hurled their music out over the crowd, and the front rows danced, but there was a sense that they were mostly waiting for the song to be over and hoping that the next would be one that they recognized.

Frustration made Michael pound all the harder on himself as he prowled the edge of the stage, as Shivers’ guitars shrieked in a blindingly fast solo, as they came back into the chorus once more, as the song thundered into the crescendo of the climax. Applause and a few cheers answered them, and someone near the front of the stage bellowed out “DB! Play ‘Fool!’ Play ‘Incidental Music!’” Both were songs from their first number one album.

Michael grimaced and flexed his six arms and the scrolling landscape of complex tattoos crawled over his naked torso. He shrugged to the others. “Sure,” he said into his throat mics. “Whatever you fuckers want. That’s why we’re here.”

A roar of delight answered him as Shivers began the intro to “Self-Fulfilling Fool,” finally hitting the power chord with S’Live that kicked the first verse. Michael began to play, his hands waving as he struck himself with the drum sticks, his insistent drumbeat booming, his throat openings moving like extra mouths as he shaped the sound. He walked to the east side of the stage, playing to the crowd there, who lifted hands toward him as if in supplication. The Voice began to sing:

You want to believe them

You don’t want them to be cruel

But when you look in the mirror

What looks back is a self-fulfilling fool

The blast came on the word “fool.”

The sound thundered louder than the band. The concussion tore into Michael, lifting him off his feet and tossing him from the stage in a barrage of stage equipment, tumbling PA speakers, and shrapnel.

The world went dark and silent around him for a long time afterward.

The light was intense, so much so that he had to shut his eyes again. His ears were roaring with white noise. He could barely hear the voice speaking to him over it. “Mr. Vogali, glad to see you’re back with us.”

He managed to crack open one eyelid. In the slit of reality that revealed, a face was peering down at him: a dark-haired woman with a gauze mask over her mouth and nose and a large plastic shield over her eyes. At least from what he could see, she was a nat. Not a joker. So this wasn’t Dr. Finn’s Jokertown Clinic. “Where…?” he started to say, but his throat burned and the word emerged strangled and hoarse.

“You’re in Bellevue Hospital’s ER, Mr. Vogali. I’m Dr. Levin. Do you remember what happened to you?”

“The others…” he managed to croak out. He tried to grab at Dr. Levin’s arm with his middle left hand, but the motion nearly made him scream from pain. The doctor shook her head. “Please don’t move,” she said to him. “You’ve a badly-injured arm, broken bones that we need to set, and we’re still assessing any other possible injuries. We’re taking good care of you, but…please don’t move.”

“The others,” he insisted. “You have to tell me.”

Dr. Levin glanced away, as if trying to see through the curtains around them. “I’ll check and see if they’ve been brought here,” she said. “Right now, I’m only worried about you and what we need to do…”

He still didn’t remember, a week later.

Michael sat at the window of his penthouse apartment on Grand Street, a specially-designed, six-sleeved terrycloth robe wrapped around him. His right ankle was locked in an immobility boot, his left leg casted to mid-thigh. Two of the left sleeves were empty, the cast on the middle arm taped to his body underneath the robe. The left lower arm…well, that arm was missing to above the elbow; too badly mangled to save, they’d told him.

That loss was something he would feel forever. The doctors had talked about a prosthetic down the road, but…He could still feel the arm and the hand. It even ached. Phantom limb syndrome, they called it. A fucking disaster, it felt like to him. All of it, a fucking disaster…

The rips and cuts from the flying wreckage and the ball bearings the bomber had packed into his bombs were beginning to heal, but his face and his body were still marred by blackened scabs and the lines of stitches. His left ear was ripped and scabbed from where its several piercings had been forcibly torn out. Three of the six tympanic membranes on his chest—his drums—had been rent open. The surgeon at Bellevue who’d sewn the fleshy strips back together and taped them said he was “fairly sure” they’d heal, but didn’t know how potential scarring might affect their sound. His left tibia had been fractured, resting now on a footstool in front of his chair; his right knee’s patella had been cracked after he’d been thrown from the stage and landed on blacktop; his face and his arms—five of them, not six now—looked as if someone had taken a belt sander to his skin. His hearing was still overlaid with the rumbling tinnitus that was the legacy of the explosion, though thankfully the in-ear monitors he’d been wearing had blocked most of the permanent damage that might have occurred.

He was alive. That, at least, was something. That’s what they kept telling him, over and over, during those first days in the hospital.

S’Live had also been brought to Bellevue; he’d succumbed to his injuries while in surgery. Shivers had been DOA on arrival. They hadn’t even attempted to revive the Voice, who had been nearest the explosion; regrettably for those responsible for cleanup, his invisibility hadn’t survived his death, either. Bottom was still alive, taken to another hospital, though he’d lost his right arm, right leg, and right eye, among other less severe injuries.

Thirty other people nearest the stage had also died, with more than a hundred wounded, some in critical condition, which meant that the final death count would be higher.

“This is all over the news,” their long-time manager, Grady Cohen, had said in an almost cheery voice back in the hospital. “It’s been twenty-four hours non-stop on all the channels all day. No one’s talking about anything else. All this has the label planning a new Joker Plague retrospective double album; they’re hoping to release it in the next few weeks, to take advantage of the publicity.” At which point DB had told him to get the fuck out of his room.

No one had yet claimed responsibility for the blast. Fox News was openly speculating that it was most likely Islamic terrorism, citing Michael’s involvement in the Committee interventions in the Middle East a decade ago and talking about how this might be retaliation; CNN was less certain, but certainly dwelled a lot on Michael’s time with the Committee, flashing old footage over and over. The FBI, SCARE, and Homeland Security were heavily involved in the investigation, supposedly.

But the explosion was no longer the front page, featured story. A week later, other events had pushed it aside, and after all, most of the dead and injured had only been jokers.

Only jokers. The marginalized ones.

In another week, Michael knew, the entire episode would all be old news, only revived if something new and provocative was uncovered or if they caught the bomber. Already, the requests for interviews were beginning to dry up, judging by the thin stack of notes his hired caregiver had given him this morning, and coverage on the news networks had dwindled to a few minutes’ update on the hour, and then only if there was some small new development.

A cup of tea steamed on the table alongside his chair, near the closed Mac Air there. Michael reached over with his upper right hand to grab it; the motion pulled at the healing scars and muscles in his chest, and he grimaced, groaning involuntarily. That caused his caregiver for this shift—a nat Latino man named Marcos—to poke his head around the corner. “You OK there, Mr. Vogali?”

“Yeah. Fine,” Michael told him.

“OK. Give me a few minutes and I’ll be in with your meds.” The head withdrew.

Michael sipped at the tea and stared out the window over the roofs of Jokertown, the ghetto of Manhattan where most of the jokers lived, just to the east. He knew that if he went to the window, he’d see, a few stories below on the street, a nondescript black car parked in the NO PARKING zone. Since the bombing, it was always there, with two tired-looking plainclothes cops inside from the Jokertown precinct, Fort Freak, watching his building.

Michael had caretakers he’d hired—people who would take care of him because he paid them. He had a few groupies—people who came to see him because he was still marginally famous and they hoped some of that glamor might rub off on them. He had this apartment and a London flat that he rented out. He had Grady Cohen, whose living was largely dependent on Joker Plague concerts and memorabilia sales. He had the cops who’d been assigned to watch him in the wake of the bombing. But beyond that…

He had no family. No wife. No girlfriend. No children, at least none that he knew of. He couldn’t even call the other members of Joker Plague true friends, though he’d inhabited the same studios and same stages with them for years. He nearly laughed bitterly at that thought: all of them dead now except for Bottom.

That still hadn’t sunk in. Bottom, Shivers, S’Live, the Voice: these were the people with whom he’d spent nearly all his time for the last two decades. At least Bottom had family: a wife (Bethany? Brittany? Michael wasn’t sure) and two kids Michael had seen in pictures but also couldn’t name, somewhere in Ohio in a suburb of one of the C-cities (Columbus? Cincinnati? Cleveland?). Bottom had called Michael four or five times in the last week—at least Michael had seen his number on the missed calls list of his cell phone. He hadn’t returned any of the calls. He wasn’t sure what to say. It was easier just to pretend he hadn’t seen the calls.

The only person (other than the well-paid Grady Cohen) who’d visited him after the explosion, who had actually come to see him while he’d been in the hospital, was Rusty: Wally Gunderson, or Rustbelt, the joker-ace who had been on the Committee with Michael, and who had been with him for the disaster in the Middle East that had led to DB’s angry resignation. No one else from his old American Idol days had bothered to do more than send a card or useless bouquets of flowers. Not Curveball. Not Earth Witch. Not Lohengrin or Babel or Bubbles or John Fortune or any of the other Committee aces or American Hero alumnae. That, if nothing else, showed DB how he was considered by them: somebody they knew, not somebody they loved.

It was 4:00 PM. Michael snatched the TV remote with his middle right hand. CNN flickered into life, with Wolf Blitzer’s sagging, white-bearded face filling the screen. “…latest on the bomber’s letter—a manifesto is perhaps the best description of this long, rambling missive—that was evidently delivered to the Jokertown Cry the day after the explosion, but not released by the authorities until just this morning. The writer claims responsibility for the Wild Card Day blast in Roosevelt Park, and also claims that he intended to die in the blast himself.” A reproduction of the letter filled the green screen behind Blitzer, with some of the text highlighted. Michael turned up the volume. “Let me read just a portion of this communication allegedly from the bomber. ‘The bleeding heart liberal scum of America, who are best exemplified by Joker Plague’s Drummer Boy, who preach that we must tolerate and accept those who bear God’s marks of sin, can no longer be tolerated, not if we are ever to cleanse the earth of their filth. The wild card virus is God’s punishment on the human race and all jokers will inevitably be purified in the cleansing fires of hell. I will purify myself with them. What I have done with my action is to set God’s plan in motion.’“

Blitzer paused as the letter vanished from the screen to be replaced by footage taken after the blast. So the bomber died in the blast—but who was the fucker? Michael saw blast victims being treated by EMTs and jokers staggering around with blood running down their misshapen faces—video he’d seen a hundred times already. “If this unsigned manifesto is indeed from the bomber, then we are, according to the experts I’ve spoken with, in all likelihood dealing with a homegrown terrorist. Let’s bring in the head of the UN Committee on Extraordinary Interventions, Barbara Baden, to talk about this…”

“Bitch.” Michael flicked off the TV. He scowled, looking out through the window once more at the Jokertown landscape. A “homegrown terrorist.” A joker hater. Someone who specifically hates me. And he’s killed himself too, the bastard.

I want to know who this son of a bitch was, and I want to know if someone helped him with this.

All five of his hands curled into fists, but he thought he could feel the missing sixth hand do the same.

“Thanks for meeting me, man,” Michael said to the imposing joker across the table from him at Twisted Dragon, a restaurant set in the indefinable border between Jokertown and Chinatown, a once-famous place to meet now clinging desperately to vestiges of its fame under the latest in a long sequence of hopeful owners. Rusty had brought back two massive plates heaped with offerings from the lunch buffet; Michael had settled on chicken fried rice and a bowl of wonton soup.

Michael’s plainclothes shadows had followed him in, taking a table near the door. One was Beastie: seven feet tall with bright red fur and clawed hands, about as unobtrusive as a velociraptor dressed in a tutu. Beastie’s partner was Chey Moleka, an Asian nat, her black hair pulled back into a tight bun under a knitted black beanie hat with the Brooklyn Dodgers logo stitched in front. Despite being in regular clothing for this assignment, her appearance still screamed “cop.”

Rusty shrugged metallic shoulders, and with one hand rubbed at the bolts that seemingly held his jaw in place; his other hand held a fork hovering over a mound of Hunan Shrimp. His skin was buffed and polished; not a trace of rust anywhere, which told Michael that Rusty had spent some time with steel wool that morning. “Hey, I was happy to do it,” Rusty said. “After all, we’re friends, right?” Michael saw Rusty glance at Michael’s torso, uncharacteristically covered by a heavily-modified T-shirt to accommodate his too-large chest and arms, the middle left hand bound underneath with an elastic bandage, the bandaged stub of his lower left hand sticking awkwardly out from its sleeve. Most of the time, DB went bare-chested so that his natural drumheads were accessible, and yes, because his muscled and tattooed torso was often admired. “Cripes, how are you doing, fella?” Rusty asked Michael. “You healing up OK? Y’know, those drums and all?” Michael saw his gaze travel quickly over the missing arm. Rusty tapped his own chest with a finger; it sounded like two hammers clanking together. “Your arms…” he began, and stopped. “Your leg’s still in a cast, but you’re getting along with those crutches,” he finished.

“It’s coming along slowly,” Michael answered. “I’m mobile, and my arm’s getting better quicker than the docs expected. The missing one…” He attempted a shrug. “It really hurts to play right now, but the docs think it’ll all come back in time. Most of it, anyway.”

Rusty nodded his great iron head. “That’s good to hear. Ghost— Yerodin, that’s her real name, but hey, she doesn’t like me to call her that—said to say ‘howdy’ to you.” He managed to look sheepish and he plopped a forkful of shrimp in his mouth, chewed a few moments, then swallowed. “She remembers you coming to the Institute, and I’ve told her about your band and all, but I haven’t let her listen to many of your songs yet. She’s so young and the lyrics, well…”

Michael waved away the apology. “No worries. Show me what she looks like now.”

Rusty pulled out his smartphone, tapping at the screen with his fingers, then turning it around so Michael could see the screen. There was a myriad of tiny scratches on the glass screen—Michael wondered how often Rusty had to replace his phone—and underneath the scratches a young black girl stared up at Michael, her hair woven into several long braids capped with brightly-colored beads. Michael couldn’t imagine Rusty managing that with his thick, clumsy fingers; he wondered who’d done the braids; as far as he knew, Rusty was still mourning for Jerusha—the ace called Gardener—who’d died during a Committee incursion into Africa, a year or so after Michael had resigned. “She’s a pretty one,” he said, and Rusty beamed.

“She sure is. You oughta come see her again soon. She’d love that.”

“I will, I promise,” Michael said. He took a slow spoonful of his soup with his middle right hand, feeling the pull on the bandaged wounds. His right hands drummed on the tabletop as he set the spoon down. It was hard to resist the temptation to tap on the T-shirt covered drumheads—a nervous habit he’d had ever since the virus had changed him—but he knew how that would hurt. It would hurt more if, once the sutures were out and the tears healed, if the natural drums didn’t work as they had. And the missing arm—that would be part of him forever, now. “I take it you’ve heard about the letter the bomber sent to the J-Town precinct station?”

“Yeah. Holy cow, that fella had to’ve been nuts. Anyone who’d set a bomb just to kill jokers, and boy, the nasty way he talked about you, and then to blow himself up…” Rusty’s hand tightened around his fork; Michael watched it bend. Rusty noticed as well; he clumsily tried to straighten it and set it down with a rueful glance. “I’ll have to pay them for that,” he said, then looked back at Michael. Rusty shook his head, his neck groaning metallically with the motion. “The other guy in your band who survived—what was his name? Bottom?—how’s he doing? It must be tough, you guys losing your friends and so many of your fans like that.”

Michael felt a surge of guilt. He hadn’t seen Bottom since the first week, and there were still all the unreturned calls. He hadn’t attended the funerals of S’Live, the Voice, or Shivers, though he’d sent—that is, he’d had Grady send—cards and flowers, saying he was still too ill to be there even though his doctor had told him he’d give Michael permission to travel as long as he promised to be careful. He hadn’t personally visited the victims who’d been hospitalized, though Grady had insisted on him recording a video from his bed, later posted on YouTube, spouting all the expected platitudes and clichés.

Friends? I don’t have friends, just a lot of bridges left broken and smoking behind me…

But he couldn’t say that to Rusty. Not to those huge, empathetic, and simple eyes. “Bottom’s doing as well as can be expected,” he answered. “And I’ll tell you, I need…I want to know more about this bomber: who he was and what he was thinking, and whether he was part of a group. I’d want to know who he is—and I’m tired of waiting for the FBI and the cops to figure it out.” The last sentence sounded too eager and too harsh, and Michael regretted letting it slip out, even to Rusty.

“After he called you ‘scum’ and said you were the one he most wanted dead, I understand,” Rusty said. Rusty didn’t seem to have noticed Michael’s escorts at their table. “Hey, you want to find him? Why don’t we figure out who this guy was together? I could help you. I’ve kinda been a detective myself. I had to find Ghost’s teacher when he got snatched…”

Michael was already shaking his head, and Rusty’s excited voice trailed off. You can’t, because if I find out there are other bastards involved, I’m going to kill them the way I’d’ve killed that bomber asshole if he hadn’t offed himself. I won’t involve you in that. “This is something I gotta do myself,” Michael told him. “You can understand that, right?”

“Yeah, sure,” Rusty answered, but Michael could see the disappointment in his eyes.

“Look,” Michael told him, “there is something you can do to help. You still have contacts in the Committee, right? Could you talk to someone there, someone you trust? See if you can find out if the Committee was involved, and let me know. Could you do that for me?”

“Sure can,” Rusty enthused. “I’ll make a few calls as soon as I get back. Hey, why don’tcha come with me? You could see Ghost.”

He should have. Michael knew that; it’s what a true friend would have done. But he shook his head. “I can’t right now. I have to see someone. You know how it is.” He signaled to the waiter for the check with his upper right hand. “Let me get this,” he told Rusty. “You’ve been a great help, Rusty. Thanks. Give Ghost a hug for me, huh?”

“Sure. You’ll come by some other time, OK?”

“Yeah, I will. I promise.”

Meaningless words and an empty promise, but Rusty beamed.

On his way out, Michael crutched over to the cops’ table. “Just so you know, I’m heading over to Fort Freak, so why don’t you two give me a ride so I don’t have to call an Uber. It ain’t like I’m gonna run the whole way…”

Beastie and Chey accompanied Michael into the station: New York’s Fifth Precinct, better known as Fort Freak. Sergeant Homer Taylor, called Wingman, was at the front desk. He glanced up as Michael slowly approached.

“Hey, DB,” he said, his drooping wings lifting a bit with the motion. Beastie and Chey moved on into the precinct’s depths. “Good to see you’re up and moving around, even on crutches. How can I help you?”

“Hey, Wingman. Can you let Detective Black know I want to see him?” Michael asked.

“He’s out at the moment,” Taylor grunted. “Lunch.”

“Mind if I wait? I’d hate to have you send out my two shadows again so quickly.”

Taylor shrugged, the wings lifting and falling with the motion. “Whatever. Help yourself to a chair. But hey, would you mind giving an autograph? My wife’s a big fan…” Taylor held out a pen and a piece of paper.

Michael repressed the sigh that threatened as he took the pen in his lower right hand, leaning heavily on the crutches. “Sure,” he said. “What’s your wife’s name?”

Detective Black entered the station a few minutes later. Michael had met Black before, during the investigation into the joker disappearances a year or so ago, then again after the bombing. Black—Detective Francis Xavier Black, according to the card he’d handed Michael when he’d interviewed him in the hospital, and called “Franny” according to Beastie and Chey, which struck Michael as an oddly feminine nickname for a dark-haired, burly nat in a cheap, rumpled gray suit, who looked like he hadn’t slept in days. He hadn’t shaved this morning, either. Black rubbed at the stubble on his chin as he saw Michael sitting in one of the chairs to the side of Taylor’s desk. He inclined his head to Michael. “Come on back, Mr. Vogali,” he said in a soft, quiet voice, and led Michael into a tiny office crammed in the rear of the precinct first floor.

As Michael lowered himself into a heavy wooden chair on the other side of a paper-stacked desk, leaning his crutches against the scarred and scratched arms, Black sat in the battered office chair there, pushing aside folders so that there was a clear space in which he could fold his hands. “I take it you’ve heard the reports about the letter.” It was a statement, not a question.

“Yeah. So this guy sent his letter to the Cry, and blew himself up in the explosion. Is that what you people are claiming?”

“That’s what the letter claims, yes.”

“So someone found the body? The remnants of the guy’s suicide vest, maybe?”

“You know I can’t talk to you about an active case, Mr. Vogali.”

“It’s not that hard a question. And if the fucker’s dead, what’s it matter?”

“It’s still an active case,” Black persisted. “Look, I have to keep my nose clean right now. Frankly, my bosses would love to find an excuse to push me out of here.” Something in his tone made Michael narrow his eyes.

“So are you still handling the case?” Michael interrupted the platitudes. “Or not?”

Black seemed to wince. “You already know that the FBI and Homeland Security are involved, as they have to be and should be. They have resources we don’t have here. I’m still in the loop and still working any local angles, but if you’re asking, no, I’m not in charge. That control’s been passed further up the chain.”

“So you guys don’t have a name yet? You haven’t identified the bomber.”

Black’s dead stare impaled him. “How many times do you want me to give you the same line, Mr. Vogali? I can’t talk…”

“…about an open case. Yeah, I get it. But the letter came to the Cry—where was it sent from? Was it local?”

“Even if it were—and I’m not saying that’s the case—what would that mean? The guy had to be here to set off the bomb anyway. Look, I understand how you must feel, but…”

“But it’s been kicked upstairs,” Michael interrupted loudly, “and because it’s just ugly jokers who were killed and injured, because it was just a Joker Plague concert in lousy Jokertown, it’s not exactly high priority. If the bomber had set off the bomb at Yankee Stadium and killed a bunch of high-rolling nats, then they’d already have figured out who he is and his face would be plastered all over the news. Yeah, I get it.”

Michael grabbed his crutches and pushed himself off the chair like a wounded spider. Black’s stare had gentled, but his lips were pressed together in a thin, almost angry line. Michael wondered who the man was pissed at; the emotions coming from Black didn’t seem to be directed toward Michael. “Mr. Vogali, I assure you that this isn’t low priority for me. Jokertown is my district. I knew people who died in that blast, too, and I want the person or persons who murdered them to be identified just as much as you do. But y’know what, I drank a lot of iced tea at lunch and I really need to take a piss. I hope you don’t mind if I do that.” Black shuffled through the files on his desk and plucked out a slim file folder, placing it down carefully on top of the stack of files nearest Michael. “I’ll be gone, oh, five minutes or so, then I’m going to come back and…” He paused momentarily, giving emphasis to his next words. “…look through that file. Thanks for stopping by, Mr. Vogali. I really hope we both find what we’re looking for in the end.”

Black pushed back his chair and moved past Michael to the door. Ostentatiously, he closed the blinds over the glass there, and shut the door behind him.

Michael watched the blinds sway, then settle. Leaning on his crutches, he reached out with his lower right hand and took the file folder from the stack. The brown, thick cover was stamped with both the Homeland Security and FBI emblems, and was labeled Roosevelt Park Bombing, 9/15.

Michael looked again at the closed door. He sat once more, then opened the file and started reading.

Michael’s brief look at the file did little to ease his mind, nor did it give him much more information. Yes, the FBI had swarmed in the day of the blast, according to Franny Black’s notes. There were three bodies near the location of the explosion that—like the poor Voice—were so badly mutilated that identification had been very difficult and slow. There were sub-files for each one; none had yet been definitely ruled to be the bomber, but two were jokers local to Jokertown, none of whom had ever done anything suspicious, according to Black’s notes. The other body was a male nat who was identified through dental records as Bryan Fisher—particular attention was being paid to that investigation, especially since Fisher was former military. Fisher lived in Reading, Pennsylvania; from the reports in the file, he had given no outward indication of being someone who hated jokers. His wife claimed he was a long-time fan of Joker Plague, who had once played a show at his army base in Germany. Yes, she knew Bryan had gone to New York for the show, and she hadn’t accompanied him because she was eight months pregnant and didn’t think it would be good for the baby or her to be exposed to the decibels or the crowds. No, the letter that was sent to the Cry didn’t sound like anything her husband had ever said or written; she couldn’t believe it was from him.

The bomb had been placed under the front of the stage, probably the night before the concert—there was a separate investigation looking into the crew who had been charged with assembling the stage and providing security before the concert. The explosive had been military grade C4 (another reason to keep Fisher on the suspect list), set off with a homemade short-range detonator—the report noted that it was indeed very likely that the bomber had been caught in his own blast.

The file had included the full text of the letter sent to the Jokertown Cry, though the original and the envelope in which it had been sent were in the hands of the FBI. Michael scanned it, his stomach roiling as he read the hateful, ugly words there.

The file only fueled his anger. The file only made him feel more frustrated and useless. He felt he understood Detective Black’s irritation.

Two days later, Michael found himself lying bare-chested on an examination table in the Jokertown Clinic as Dr. Finn removed the stitches from the torn membranes that were the natural drumheads in Michael’s body. The tattoos covering his arms, chest, and back were stark against his flesh. “There, that’s the last of them,” Dr. Finn said. The doctor’s centaur-like body stepped back, the sound of his hooves muffled against the tile by elastic booties. “Whoever stitched you up at Bellevue did a nice job. Everything looks good and it’s healing up nicely so far—better and faster than I’d expect, in fact—but I don’t know how bad the scarring might be or how that might change the sound. That’s something you’ll find out, but I wouldn’t advise banging away on them just yet. Give them another few weeks.”

Michael shook his head. “Jesus, doc, you don’t understand…”

Finn laughed. “Oh, I think I do. Just take it easy, OK? Nothing too strenuous, or you’re going to be back here looking for more stitches, or worse, picking up an infection.” He pointed at the computer monitor on the desk in the room, where several X-rays were up. “Those are from your leg and your arms. They’re all healing faster than I’d expect, too—one good trait the wild card seems to have given you is the ability to recover more quickly than normal. I think we can move you to a walking cast on the leg as long as you promise to be careful, and splints for the broken arm to replace the casts. The amputation is pretty much healed; we can start looking into a prosthetic for you soon. Sound good? You’re going to need some extensive PT afterward to get full range of motion back everywhere in general, I expect.”

Michael grunted. With his lower right hand, he tapped the bass membrane and flexed the throat opening on that side. A low, resonant doom answered, reverberating in the room. “Ouch,” Michael said, grimacing. “That fucking hurts.”

“Good,” Finn told him. “That’ll keep you from using them too much. Sounded decent, though.”

“I guess,” Michael said. “Hurt like a sonofabitch, though.” Michael rubbed carefully around the ridged outline of the membrane, sliding a finger over the knobby ridge of healing skin. The remnants of his missing left arm flexed, as if it wanted to strike the drumhead closest to it, though it was far too short for that.

“All right,” Finn said. “Let me get Troll to fit you in the walking cast and splint. And I’ll see you again in a week.”

“Whatever you say, doc.”

Finn walked out of the examining room, his tail sweeping around as he turned. Michael’s phone buzzed; he fished it from his pants pocket and looked at the screen, staring at the name there for several seconds before he stabbed the Accept Call button with a forefinger. “Babel?”

“No, this is Juliet,” a woman’s voice answered. “Ink. I’m Barbara’s assistant now.”

“Hey, Ink,” Michael said. “Good to hear your voice again. What’s up? Let me talk to Babel.”

There was a dry laugh from the other side of the receiver. “Mizz Baden asked me to call for you,” she said “She said Rusty told her that the two of you are playing detective.”

“Rusty’s the one who wants to play detective, not me,” Michael answered. “I just want to make sure the bastard’s dead, that we know who it is, and that if he had help, we get those assholes too. So I take that the Committee’s been involved in the investigation?”

“It landed on Mizz Baden’s desk, briefly. She and Jayewardene decided it wasn’t in the Committee’s purview.”

“What?” Michael’s voice rose. “Why’d the Committee pass on the bombing?”

Michael could hear Ink take another breath, as if she were deciding how much to say. “It’s a matter of priorities and importance, DB. Mizz Baden said you wouldn’t understand that. She’s sorry about what happened with your band. But you’ve no idea of what we’ve…”

“Are you telling me that the bombing in Jokertown isn’t important enough, Ink? Is that what you’re saying? People died. People I’ve known for decades.” Michael wondered at his own careful choice of words: “people,“ not “friends.”

There was a sigh from the other end of the line. “You don’t understand, DB. You can’t. I’ve given you all I was told. Mizz Baden thought that since Rusty asked, you deserved that much, but I don’t have any more information than that. Sorry. I hope your recovery’s going well. I’ll tell her I talked to you.”

“No, no. Hang on, Ink. Give me some help here. Jesus…”

“DB, the bombing was a local issue,” Ink said, “not an international one.”

Michael couldn’t quite decipher what he was hearing in that statement, what Ink was saying or not saying. “OK… So the person responsible’s here in the States? I already figured that out.”

Another pause. “Mizz Baden…she believes the bomber was even more local than that. That’s really all I can tell you.”

“Are you saying the guy’s here in New York?”

There was nothing but silence on the other side of the line. Then: “Mizz Baden wanted me to call you because Rusty asked and she cares very much for him and all he’s done. He’s a good person, a kind one. I did, though, as Mizz Baden’s assistant, see the files on the bombing. Let me ask you a hypothetical question, DB. What if the person who did this isn’t so different from you? How many people have we hurt in the pursuit of what we think’s right? For that matter, what is ‘right’? Who has the most reason to hate jokers, DB? Who?”

“Riddles and questions? That’s all you got for me? Damn it, Ink…”

“I’ve told you all I can,” she answered. “Mizz Baden said to tell you she wishes you luck. Now, I have other work I need to do. Goodbye, DB.” And with that, Ink was gone.

“Yeah? Well, fuck you too!” Michael shouted into the dead phone, startling Troll, the nurse, who was walking into the examination room with an assortment of equipment in his arms. The giant’s eyes widened.

“Not you, Troll,” Michael said. “Just the world in general.”

The scene at the Jerusha Carter Childhood Development Institute was chaotic. Once past the courtyard with its huge, spreading baobab tree, looking like someone had planted a tree upside down, Michael entered a large, open room. The armless, legless trunk of an infant floated past Michael’s face as he opened the door, the eyes in a mouthless head large and plaintive, with dark pupils that moved to track on Michael’s own gaze as it floated silently past him; the slits that served as nostrils flexed, as if the child were sniffing him. There were joker children seemingly everywhere in the single large room, of all conceivable twisted and distorted shapes, with an army of attendants, mostly jokers themselves, moving among them.

One was a young boy who looked perfectly normal except that he seemed to have the hiccups; with each spasm, he exhaled a blast of flame. An attendant stood alongside him with an asbestos blanket and a fire extinguisher, but otherwise didn’t touch the boy.

A slug-like body with a human head tracked a slimy path over the tiles, pulling itself along with rail-thin arms. One young girl’s body was covered in putrescent boils, the smell coming from her like that of days-dead animal. A boy who looked to be about five started to cry, then suddenly dissolved into a puddle of brown sludge, his clothing lying on top of the pile; one of the attendants came over with a bucket, a snow shovel, and broom and began scooping up the mess. “Sorry,” she said. “He does that when he gets upset…”

“Hey, fella!” Rusty’s boisterous voice called out, and a metallic hand clapped him hard on his upper shoulders. Michael staggered forward under the blow. “Sorry—didn’t mean to hit yah so hard. But look, you’re outa your cast and into a boot, and your arms, too…That’s great. Betcha feel a lot better.”

“Yeah, I do,” Michael told him. “I thought I’d let you know that Ink, Babel’s assistant, called me, so thanks for reaching out to her.”

Rusty grinned, his steam-shovel jaw opening. “So did she have anything good to tell us?”

Michael heard the “us” and ignored it; he wasn’t going to encourage Rusty to keep playing detective. “Not really. The Committee passed on the investigation. Otherwise, she just talked in circles without saying much.” Michael shook his head. “Thanks for trying, anyway. So this is where you spend all your time now instead of running around with the Committee? These are all orphans like Ghost?”

Rusty grunted. “You betcha. These are the kids nobody wants. Me and you—we both saw what happens to kids like this in Iraq, and I saw lots worse than that in Africa when me and Jerusha were there. Cripes, the same thing happens here, too—it’s just that no one ever wants to talk about it. There are parents can’t handle a kid once their card turns, or maybe they died too, or…” Rusty’s voice trailed off again as Ghost came running toward them. “Hey, Uncle DB,” she said. Her voice still had the lilt of Africa in it. “You came to visit?”

“Yeah,” Michael said, wrapping his good left arm and two right ones around her and lifting her up. The scars on his chest protested; he ignored that beyond a grimace. “I haven’t seen you in way too long. Look at you—you’re getting so big.”

“I’ll be bigger than you or Wally one day.”

“Maybe you will,” Michael told her, laughing. “But not if I squeeze you real tight.” He started to tighten his arms around her; Ghost simply went insubstantial and dropped away from him. She grinned up at him, and glided off toward the rear of the room. “She’s growing up fast,” he told Rusty. “Is she still…?”

“The episodes? Yeah, they come and go. Most of the time she’s just a little girl, but she still has problems being with the other kids, especially if she gets frustrated. And sometimes the dreams and memories get to her, and she’s the child soldier who wanted to kill me. But it’s getting better.”

Michael looked around the room, at all the joker kids. “Do any of them ever get adopted?”

“Not enough. We’ve had a few of ’em adopted, mostly by other jokers. Cripes, these kids are the really damaged ones, the ones that are the most difficult to handle, sometimes even dangerous. That poor kid over there…” Rusty pointed his chin to the boy who hiccuped flame. “That’s Moto; the kid’s already been bounced from four foster homes, and he’s nearly burnt down this place a few times besides. Who wants a child who can set his bed on fire because he has an upset tummy, or gets too excited or frightened?” Rusty shook his large head dolefully. “Hopefully he’ll eventually learn to control the response, but maybe he won’t. Some of these kids will just…well, age out of the Institute at eighteen. Or die before then. The virus ain’t kind to most of ’em. Not like it was to us. But I’ll tell you what; we really appreciate the money you’ve sent us every year. That means a lot.”

“It’s the least I can do,” Michael answered. And that’s true. All I’ve done is the very least, and that’s all I’ve done for a long time…

Then change that, he thought, but it was a resolution he’d had a few thousand times before, and one he’d never kept. Change that.

Michael noticed that Rusty was looking down at the floor. The legless slug-child had dragged himself over to Rusty; he was crying, and Rusty crouched down to pat him, ribbons of slime clinging to Rusty’s fingers and pulling away from the kid as he did so. “Y’know, fella, some of these kids hate themselves, hate what they’ve been turned into. They can’t stand the pain or the abuse they’ve received. What kind of way is that for anyone to live? How do they get through it? That’s what I worry about with them all. I wish there was more I could do, but…”

Rusty was still talking, but Michael had stopped listening.

Some of the kids hate themselves…Who has the most reason to hate jokers, DB…? All jokers will inevitably be purified in the cleansing fires of hell, and I will purify myself with them…

The words Rusty had just spoken, the question Ink had asked him, the bomber’s manifesto…

As he left the Institute later, Michael pulled his smartphone from his pants pocket and hit a button. The call went nearly immediately to voice mail. “Hey, Grady,” he said after the beep. “It’s DB. Look, I know you’ve always kept this shit away from us, but could you send me any nasty mail—either e-mail or snail mail—that came in for me just prior to the Roosevelt Park show? Maybe up to three days beforehand? Send it to me, would you?—envelopes and all if it was snail mail, and with the full headers if they’re e-mail. I appreciate it. I’ll touch base with you later, man.”

Grady ended up sending a couple dozen pieces to Michael: mostly e-mails and a few actual letters.

Michael read and re-read the missives over the next day, pondering what to do with them. It was a depressing read. As manager, Grady had always passed along to the band the complimentary fan mail they received; he held back “the crazy stuff.” The vitriol, the anger, the insanity that Michael glimpsed in the missives was saddening. Some of it was simply former fans ranting that the band’s new music sucked, that they’d lost their edge—those were the least offensive. However, even with the nastier notes, most didn’t use the language that had been in the bomber’s manifesto. The tone might be ugly and mean, but there were no threats against life.

Except for four: three e-mails and one letter.

Those four were far more visceral and ugly: written by people who claimed to hate them for the jokers they were and the people they represented, who believed (as the bomber evidently had) that they were somehow cursed by God, that they were abominations or sinners being punished or symbols of humankind’s downfall, that they should all be purged and eliminated: “smears of ugly shit that need to be wiped off the ass of the Earth forever,“ as one of the writers put it.

Michael had experienced, viscerally at times, the hatred and bigotry toward jokers elsewhere in the world, but had been rather more insulated from it in the countries where Joker Plague had been popular. This was a blatant reminder that here, too, there were many people who shared the bomber’s view of those who’d been altered by the wild card virus, who believed that those infected had somehow made a choice about how the virus had affected them, and that the deformities given them were a reflection of inward flaws or sins.

For those people, jokerhood was a divine punishment. For them, that punishment alone didn’t seem to be enough. Michael forced himself to read the words, but they burned inside him.

You deserve to die. God has placed the irrevocable sign of your sins and your parents’ sins on your very body. I’ll force you to crawl on your belly with those arms or yours, like an wretched spider, then I’ll rip off each one of your spider arms, slowly, and listen to you screaming and begging for me to stop. I take your drumsticks and ram then like stakes into those drums on your chest. I’ll watch you writhe and bleed and curl up and die. Satan will come and take your soul to hell and eternal torment and I’ll laugh…

The unsigned letter had been posted from the Jokertown post office. Michael passed on the e-mails to the tech who maintained the Joker Plague website, asking him to see if he could figure out from the IP addresses in the header whether any of them came from New York City and especially from Jokertown: one did, and his tech had tracked down the street address.

Michael decided it was time to ditch his Fort Freak shadows. That was easy enough to accomplish; Beastie and Sal, as well as the other teams assigned to the task, habitually stationed themselves near the front entrance to Michael’s apartment building. There was a dock entrance to the rear of the building which led out onto another street. It was simple enough to call for an Uber cab to meet him there. He gave the somewhat startled Uber driver the address and sat back in the seat, wondering what he was going to say if someone was there. He tapped one of his healing drums gently, the slow and painful beat stoking the anger.

The address was an apartment building just off Chatham Square; Michael watched the garish, unlit neon sign of a naked, four-breasted joker slide by: the facade of Freakers nightclub, now long past its prime (if it had ever had one). The entire neighborhood had seen better days; the Uber driver, a nat, was distinctly uncomfortable with Michael’s request to wait for him, but a fifty-dollar bill elicited a promise that he’d stay for fifteen minutes. Michael got out and walked up the cracked concrete steps to the front door; it opened when he turned the knob—not locked. The address the tech had discovered gave the apartment number as 2B; Michael took the stairs up and found the door of 2B at the rear of the building.

He stood outside for a moment, taking a long breath. The hallway smelled like a stale diaper, and the walls appeared to have been last painted back in Jetboy’s day. Michael knocked on the door, holding the thumb of another hand over the glass peephole.

“Who is it?” a thin, high voice called from inside.

“Drummer Boy,” Michael answered.

“Yeah, sure,” the muffled voice answered, “and I’m Curveball.” The door cracked open, and Michael was staring at a hairless face that appeared to have been molded from wet beach sand by clumsy fingers. Pebbly eyes widened in the gritty face, and small crystalline specks drifted down like tan, sparkling dandruff.

“Oh, fuck,” the joker said. The door started to close, and Michael pushed it open again with three hands. The door crashed hard against its hinges, and Michael entered the apartment to see the sandy, naked, and evidently male figure starting to run toward a back room. Michael lunged forward, stiff-legged in the walking cast, and grabbed at the joker’s arm with his good left one. His fingers closed around the joker’s arm.

The arm crumbled and broke like a dry sandcastle where Michael had clutched at it. Sand crystals drizzled through Michael’s fingers; the hand and forearm hit the wooden floor and shattered. “Shit!” Michael shouted as the joker clutched at the remnants of the arm. A thin liquid—not blood, but clear—dripped sluggishly from where the arm had broken off. Behind him, Michael could see another room illuminated by the glow of a computer monitor. He also noticed that the floor everywhere in the apartment was gritty with sand crystals, drifted into piles in the corners.

“Fuck!” the joker screamed. “Look what you’ve done. It’ll take me a week to grow that back. You asshole sonofabitch! Damn, that hurt!”

“I just wanted to talk to you…” Michael began, but then the anger surged again, and with it a sense of despair. Not dead. The bomber said he was going to blow himself up. The concussion of a blast would destroy this guy. Michael pulled out the folded paper on which he’d printed out the e-mail and shoved it close to the joker’s face. “Did you write this?”

The joker glanced at the paper. “Yeah. So what? All I did was tell you what half of your old fans are thinking. You’re a washed-up hack and your new music sucks. Deal with it.” He spoke without bravado or heat, his high-pitched voice sounding more apologetic than angry.

“Did you set the bomb at Roosevelt Park?”

“What?” The joker’s voice was a piercing shriek. “You think I did that? I…God, are you insane?”

Michael shook the e-mail at him. “This says you want me to die.”

“That’s hyperbole, dude. I was trying to make the point that you’re already dead creatively. It don’t mean I went and killed a whole bunch of jokers because I think you’re a poser. I wasn’t there; I wouldn’t do that.” The joker continued to rub at his broken arm. Michael could see the broken ends knitting together already, the sandy skin there darkening as the fluid leaked out. “Damn, you really don’t like people telling you the truth about yourself, do you?”

Michael swung away from the joker, moving past him into the next room. The joker followed him as he prowled the room, not knowing what he was looking for: electronic wiring, packets of C4, even a ticket stub from the concert, anything that could indicate this guy was somehow involved in the bombing, even as he argued with himself internally. He’s not the one. Not the one…

There was nothing incriminating in the room. Nothing to indicate that this person could have been the bomber. Everything about this screamed that the joker was just one of the sad people who could talk aggressively and puff himself up online but was nothing but bluster in real life.

This was a dead end.

Michael put the copy of the e-mail on the joker’s desk. “What’s your name?” he said.

“They call me Sandy,” he said, then to Michael’s shake of his head. “Yeah, I know. I’m just a big fucking joke.”

“OK, Sandy. Listen to me: if you say anything about me being here, I’ll have you arrested for making death threats—and I can guarantee that if I do that, the FBI will be looking at you for the bombing, too. Send me or anyone I know anything else like this crap, and you’ll have the feds at your door.”

“I didn’t do it,” Sandy said again. His voice was sullen. The black pebbles of his eyes were downcast.

“Then all you have to do is make sure you keep your mouth shut,” Michael told him. “I don’t ever want to hear from you again.” With that, he headed toward the door, passing the dried out husk of the joker’s arm in the front room. “Sorry about that,” Michael said as he left, his shoes scraping against the glistening sand grains on the floorboards.

When Michael reached the street, he found that the Uber driver had left.

Michael swung by the Carter Institute a few days later, finding Rusty standing under the baobab tree in the courtyard. It was misting, and streaks of rust were beginning to run down Rusty’s arms. Wally saw Michael approaching and waved to him over the joker kids running around the courtyard, most of whom he’d met the other day. He could see Ghost among the ones closest to Rusty. She also waved to him; he waved back. “Hey, DB!” Rusty bellowed. “Good to see ya, fella.”

Under the leaves of the baobab, the mist turned into large, random drops. Michael pulled up the hood of his jacket. “You too.” Michael hesitated, and Rusty jumped into the conversational lacuna.

“So we still have to find the bomber, huh?”

“Yeah, I do.” Michael figured Rusty wouldn’t catch the emphasis he put on the “I,” but thought he’d try anyway.

“Maybe we could put up a post on Facebook—we’ve got a page there—saying ‘If anyone knows anything about the bombing in Roosevelt, please contact us.’ And we could do the same thing on Twitter. You have a Twitter account, right? Hashtag #bomber…”

Michael was already shaking his head, and Rusty slowly ground to a halt. “Look, Rusty, you know as much as anyone about what goes on here in Jokertown. Can I run something past you?”

That brightened Rusty’s expression. “Sure. Anything.”

“Good. Tell me if you’ve heard someone talking like this…”

Michael handed Rusty a copy of the unsigned letter that Grady had sent him. The joker’s thick, clumsy fingers took the paper and unfolded it. Drops fell on the paper from the leaves; Rusty ignored them, scanned the letter, his breath sounding like steam as he read. He snorted nasally as he looked up at Michael with large sad eyes. “This is one sick fella,” he said. “You think the bomber, the guy who sent the manifesto, is the same person who wrote this?”

“I don’t know. Maybe. It’s a hunch. The thing is…You’re in Jokertown more than me. Have you heard of anyone around here saying these kind of things, especially directed toward me or Joker Plague? A joker like us. Maybe someone new to the area.”

Rusty scraped at the brownish-orange stains on his arm with a finger, leaving a trail of bright metal. “A joker? Saying those kind of things…?”

“I gotta know,” Michael said. “I gotta know who did this, and I gotta know he’s dead, and I gotta know if anyone helped him. I lost…I lost…” Michael stopped himself, bottling up the grief and fury that was threatening to spill out suddenly. He was grateful for the dripping leaves as he took the paper back from Rusty.

Rusty’s hand touched Michael’s top shoulder gently. “Hey, fella, I understand,” he said. “Look, I have another idea. You ever hear about that Sleeper fella? He’s been around since Jetboy, they say. No one knows Jokertown like him. If you can find him–“

Spread enough cash around and you can find anybody. Croyd Crenson, according to the walrus-faced joker at the newsstand on Hester, could be found in the back room at Freakers. “Look for someone who looks like he’s been swimming in an oil spill,” the walrus told him. “And don’t touch him. He’s sticky.”

Pushing in through the double doors between the legs of the giant neon stripper that marked the entrance to Freakers, Michael was immediately assaulted by the smells of stale beer, urine, and cigarette smoke. He forced himself not to take a step back. The faces of the joker patrons inside turned to him, and the bartender—a tentacled joker as wide as he was tall, with eyes as big as saucers–blinked and spat. “Hey, looky, a celebrity,” he announced in a booming voice. “Didn’t you used to be important?”

“I’m looking for the Sleeper,” Michael said.

The bartender waved a tentacle vaguely toward the back. “In our champagne parlor. For VIPs only.”

Michael pulled out his wallet. “How much to be a VIP?”

“One Benjamin. Fifty for the champagne, fifty for the girl.”

He tossed down a hundred. “Here. Hold the champagne. Hold the girl.”

The champagne parlor was lit by a single overhead fluorescent tube, giving off both a cold, pale light and an annoying loud hum from the ballast. Along the walls were shadowed booths where horseshoe-shaped couches upholstered in Naugahyde wrapped around small tables.

Only two of them were occupied at the moment. A busty teenaged stripper was squirming in the lap of a well-dressed nat in one. In the other, a greasy-looking joker sat alone behind a small table, the fluorescent sparking highlights from the glossy skin. He was nursing a beer.

“You Croyd Crenson?” Michael asked him.

“Who wants to know?” The man looked up from his beer. “Fucking Drummer Boy.” He nearly spat the name. “Your music’s total crap, you know? Tommy Dorsey, the big bands, Sinatra…now that was music. Everything since…noise.”

As Michael’s eyes adjusted to the dimness, he could see that there were various small objects stuck to Croyd’s body like the dark spots of flies on a strip of fly paper: napkins, paperclips, two Bic pens, what looked like a torn strip of a band poster—not for Joker Plague—half a coffee mug upside down on his right bicep, and, disturbingly, what looked like someone’s toupee on his chest.

“Everyone’s a critic,” Michael responded.

Croyd laughed. “Yeah.” Eyes the color of old ivory moved in the oily face, tracking down to Michael’s missing arm, then coming back up. “I’m Crenson. Why do you care? What do you want from me? It ain’t like we’re old friends.”

“I’m looking for someone.”

“Do I look like the missing persons bureau? Go talk to the fucking cops. Leave me the hell alone.”

“I don’t want Fort Freak involved in this.”

Croyd laughed at that. He took a sip of beer from the heavy glass mug in his hand. Michael noticed that he didn’t have to close his fingers around the glass; it was already well-stuck to his palm. Strands of viscous black pulled away from Croyd’s lips and snapped as he brought the mug back down hard on the table. It shattered, leaving broken glass glued to Croyd’s hand. The Sleeper stood up, the heavy wooden chair on which he was sitting adhering for a few seconds to his butt before dropping back down with a bang. “I don’t give a rat’s ass what you want. I said leave me the hell alone.” He held up his hand with its glittering shards. “Unless you want this smashed across that ugly face of yours.”

Michael didn’t move. “You don’t like my music. Fine. I think that big band crap sucks dog turds myself. But no one ever blew up Glenn Fucking Miller. And no one seems to care who blew up my bandmates and my fans.”

Croyd snarled. “I read the Cry. The fucker blew himself up. End of story.”

Michael shook his head. “Maybe. Maybe not. Damn it, I need to know who this guy was.” The words quavered in the air, the emotion raw and tearing at Michael’s throat. “Over the years, the things you’ve done…had to do…you have to understand how I feel.” All five of Michael’s hands lifted, the stub of his missing one moving in sympathy. “I gotta do something. I can’t just sit and wait.”

Croyd lowered his hand a few inches. He was still standing, but he didn’t move toward Michael. “And you think I might help you find the bomber?”

“They say you know Jokertown like the back of your hand.”

That made him laugh again. “The back of my hand changes every time I go to sleep. Your bomber is probably dead.”

Michael shrugged. “Probably. I want to know for sure. And I want to know that he didn’t have other people helping him.”

“You looking for revenge, Drummer Boy? You going vigilante?” Under the rubbery, slick surface of his face, his mouth turned up in a smirk. “Fuck it. What’ve you got?”

“Here,” Michael said. He took the copy of the unsigned letter that Grady had sent him from his pocket, unfolded it, and carefully put it on the table in front of Croyd. The joker squinted down at it but didn’t touch it. Michael could see his gaze scanning the writing. Croyd sniffed. “That’s one sick, angry fucker,” he said. “He’s right about your music, though.”

Michael ignored that. “All I want from you is this: have you heard anyone around here saying these kind of things, especially directed toward me or Joker Plague. A joker like us. Most likely someone new to J-town.”

“And if I have? You taking this to the cops?”

Michael shook his head. “No cops. Just me. And I won’t be telling anyone where I got the information.”

Croyd sniffed again. His hands closed around the glass shards; it didn’t seem to bother him. He sat again.

“I might be able to help. I haven’t seen this guy in a few weeks, but there was a joker whose card had just turned who came in here. He was…angry about what had happened to him. Raving about God and sin and all the rest of the pious garbage that’s in here.” He pressed a pudgy forefinger on the letter. When he lifted the finger, the paper came with it. He looked annoyed and slapped the paper against the side of the table a few times; it ripped and left a corner on Croyd’s forefinger. “The bouncer threw him out. Real gently.”

“What was his name, Croyd?”

“Don’t know, but…he had more arms than you. At least twelve, I think. A head like a praying mantis, fringed with purple hair around the neck. Just a long tube for a body: red with iridescent blue spots all over it. He walks on those hands like a centipede, and lifts up the front of his body a little to use the front ones—one of those was holding a stupid bible. Ask around. Someone else maybe knows his name and where he lived.”

Michael felt his stomach knot. Maybe…maybe he’s the one… “Thanks, Croyd,” he said. “I appreciate, more than you know. I’ll have them send you back another couple beers.” He turned to leave the room, and heard the Sleeper chuckle behind his back.

“You think it’s going to help you to know for sure?” Croyd asked him. “It won’t. Nothing makes that kind of pain go away. Nothing.”

It took two days of discreet inquiries, but the Sleeper was right; the description was solid enough that Michael eventually had a name and an address for the joker: a rundown apartment building on Allen Street near Canal.

The super was a joker whose handless arms were tentacles covered in octopus-like suckers, and whose face was shaped like a rubbery, upright shovel, the eyes squashed together at the apex. “Whoa!” he said when Michael knocked. “You’re DB!”

“Yeah. I’m looking for a guy named Robert Krieg—red with blue spots, a dozen hands or so? He lives here, I’m told.”

The super grunted assent. “You mean Catapreacher? Yeah, he lives here. Or he did.”

“Look,” Michael told the super, “you have keys to his apartment, right? Mind if I have a look inside?”

The spade-face squinched up. “Not supposed to do that.” His voice trailed off hopefully; the tentacle arms swayed. But he didn’t have any issue handling the envelope Michael passed to him, manipulating it easily as he opened it and scanned the bills inside. He grunted, a tentacle snaking the envelope into a pants pocket.

“I suppose it wouldn’t matter much. God knows how Catapreacher’s left the place. Come on—he’s on the first floor.”

The apartment smelled of moldering food and stale air. The super gave a short laugh. “Look at this crap. This is the kind of shit I have to deal with all day, every day.” He waved a hand at the cluttered, messy apartment, strewn with clothes and paper. “Krieg—he don’t appreciate the name I gave him—just moved in here, what, fuckin’ two months ago. Didn’t get his garbage out last Tuesday. I had ta fuckin’ do it. None of my renters like him. Always going on about how awful the place is, how he hates jokers and Jokertown—like he had a lotta room to talk—and spouting all kinds of religious shit.”

Michael wandered around the small apartment as the super talked. Roaches scattered as Michael approached. There was a bible on the coffee table, a streak of something black, oily, and sticky on the cover. The bible was surrounded by half-empty Styrofoam cups of to-go coffee and paper plates with hard slices of frozen pizza curled on them. Flies buzzed around the remnants, with maggots writhing on the cheese. Next to a CD player on the floor, there was a stack of Joker Plague CDs. Michael picked them up, shuffling through them. The super laughed as Michael glanced at the covers.

“Hey, he mighta had your CDs, but Catapreacher didn’t like your band, I can tell you,” he said. “I heard him going on about that once myself, so it beats me why he decided to go hear you guys at Roosevelt Park. I was gonna go myself…”

Michael’s breath caught in his throat as he set the CDs back down. “He was at Roosevelt Park?”

“Yeah. The guy’s really fucked up—in more ways than one.”

Michael moved into the bedroom: no actual bed, just a nest of rumpled blankets. On the floor next to it was a framed photograph of a rail-thin young man in a black suit, standing alongside a lectern and holding aloft what could have been the same bible that was in the front room. An out-of-focus cross was prominent on the wall behind him. Michael assumed he was looking at a photograph of Robert Krieg before the wild card virus.

It’s him. It has to be. A disgruntled joker who hated what he’d turned into, a religious fanatic missing since the bombing and with an admitted hatred for Joker Plague. It had to be him.

Michael was certain when he looked into the bedroom closet. There were no clothes there at all, only a table with the legs sawed off so it was no higher than a few inches off the floor. The surface of the table was strewn with bits of wire, a soldering iron, the remnants of two disassembled clocks, and several olive-colored Mylar wrappers. Staring at the mess, Michael shivered involuntarily.

It’s him. I’ve found him. He thought he should be feeling a surge of vindication, of triumph at the revelation, but instead he only felt empty. He remembered what Croyd had said. The anger, the rage he’d been holding in; it was replaced by…nothing. He stared at the evidence as his several fists clenched and unclenched. He tapped at his chest, and a soft doom filled the apartment as his throat opening flexed to shape the note.

A funereal, low, and solitary beat.

Voice, S’Live, Shivers, all dead because of this guy. Bottom disfigured. And me, the one he hated most of all, on my way back to normalcy—whatever the fuck that is…All the innocent jokers who’d come to watch us dead or hurt.

And no one to punish. No one on whom to wreak vengeance. It isn’t fair. It isn’t right.

Nothing left to do except call Detective Black and tell him where to come find the evidence.

“Did you know anything about what Krieg did before he came here?” he called out to the super. “Did he have any friends, people he might’ve been working with?”

“Dunno what he did. And he don’t have any damn friends: a total loner. Nobody gives a flying shit about the little bastard and his preachifying. All I know is that if he don’t hand me his rent on Wednesday, maybe I’ll just toss all this crap in here out on the sidewalk. Especially now that I see how he’s keeping the place.”

Michael gave a brief, dry laugh. “I hate to tell you this, but Krieg’s dead.”

“Huh?” The super’s voice sounded genuinely startled. “When did that happen? Hell, he called yesterday to tell me that he was finally getting out of the hospital on Wednesday.”

The statement stole Michael’s breath momentarily. The room seemed to lurch around him once. “Getting out—?” He closed the closet door and went back into the front room. The super was standing at the door, tentacles waving, one of the sucker pads holding a smoking cigarette.

“Yeah. The bastard was one of the people hurt when that bomb went off. They took him to the Jokertown WIC Center on Grand. Been there ever since, not that he ever contacted me to tell me until that call yesterday. I thought that was why you was here. Doing that sympathetic good-guy thing for a fan, even if Catapreacher—God, he hates it when I call him that—ain’t really a fan. Kinda ironic, I guess.”

“Yeah, kinda,” Michael told him. His stomach had knotted again, tighter than ever. “Look, thanks for letting me poke around. I guess my manager gave me the wrong info. Sorry to have bothered you.”

“No problem,” the super said, tapping the pocket with Michael’s envelope. “No bother a’tall, DB. Hey, you want to leave a note or something for Krieg? In case he actually pays the goddamn rent?”

“No,” Michael answered. “I’ll stop by and see him in person sometime.”

Michael heard the door open, then close, followed by the patter of several hands slapping the floorboards. When he heard the snap of a switch and saw the wash of yellow light fill the front room, he stepped out of the bedroom where he’d been waiting.

“Krieg,” he said. “I know it was you. You’re the bomber.”

Michael didn’t know what he’d expected as a reaction. Surprise, certainly, and perhaps fright as well. Or perhaps anger. He got none of those, and felt a wash of brief disappointment. The centipede-like body was heavily bandaged; the two rear hands were booted, not unlike Michael’s own leg. The joker’s mantis head swiveled toward him. Round and pupil-less dark eyes stared as the fingers of its several hands flexed and unflexed on the floorboards. The insect mouth opened, and the voice that emerged sounded cartoon-high and thin. “You were supposed to be dead,” Krieg said.

“So were you.” Michael was bare-chested, his injuries visible: the scars, the splint still on his middle left arm, the stub of his lower left arm sticking out uselessly. He thumped hard on the bass membrane with his right hand, ignoring the pain. He shaped and tightened the sound, focusing it on Krieg’s body. The concussive blast hit the joker, knocking him over and sending him tumbling against the wall of the room. The joker squealed and struggled to right himself. The front of his body lifted, his front two hands outstretched toward Michael.

“My Lord God…” Krieg began, then seemed to choke on the word as Michael brought his hand up again, fisted as if ready to strike the drums of his chest again. Michael saw Krieg swallow hard. The mantis eyes blinked; his front two hands were clasped together now, as if in supplication or prayer. “Yes, my own death is what I wanted as well,” he continued, “but the Lord saw fit to intervene. I was ready for that, but just as I pushed the button, another joker shoved between me and the stage. It…whatever it was…had a hard carapace, and that shielded me from the blast. It wasn’t until I woke up in the hospital that I heard on the news that you’d survived too.” The face scrunched in a scowl. “I suppose…I suppose this is what the Lord wanted of me. It was His hand that saved me. Like Isaac, who Abraham was ordered to kill, I was spared. As for you, you only lost an arm and broke a few bones. Hardly the punishment you deserved.”

Michael struggled to keep his voice calm. He wanted to beat on his chest, wanted to pummel the joker with a fatal barrage of percussion: as he’d once done with the Righteous Djinn in Egypt, as he’d done to others in Iraq. His missing left arm throbbed, as if it heard his thoughts. “God had nothing to do with it, you fucking idiot!” The words were hoarse and loud, ripped from his throat as he shouted. “God didn’t want dozens of jokers to die. God didn’t want Shivers and S’Live and the Voice to die. You did, you bastard! You did!”

Blink. The mantis head looking briefly toward the ceiling as if searching for words there. “Leviticus 21:18—‘No man who has any defect may come near the Lord’s altar: no man who is blind or lame, disfigured or deformed.’ Look at us, Drummer Boy. We are cursed for our sins. Psalm 37:38—’But all sinners will be destroyed; there will be no future for the wicked.’ Don’t you see? There you were, you and your fellow abominations, making a mockery of the Lord with your celebration of your disfigurements, with all the other sinners and cursed ones shouting your praises and buying your records. And you…you especially, pretending that you were doing good in the world: the great DB, raising money for charity with one set of hands and raking in more money with the other. Accepting the idolatry of the cursed ones. The aces—they’ve been raised up by the Lord God, gifted by Him for their goodness in their souls. But you…you’re just a joker like the rest of the cursed ones.”

“Just a joker?” Michael raged at the man. “You think that’s all I am?” Again, he beat on his chest: two strikes, this time, directed right at the man, the low pounding reverberating. He saw Krieg’s body respond; ripples moving down the long tube of its body. It will be easy. Quick. That body’s fragile and soft…

Krieg cowered, and Michael stopped. The joker raised its front hands again. “You must know you’re a sinner like the rest,” he said, “even as you pretend to be as good as the believers, even as you prance on your stages. You, more than any of the others, are a symbol of all…of all that is wicked in this world…and the Lord spoke to me. He said…He said…”

Krieg was weeping now, whether from pain or from fear, Michael didn’t know. Tears flowed from the bulging eyes. The bandages on his body were showing spreading splotches of red: the concussion of Michael’s drums had torn open the wounds underneath. “He said that as penance for my sins…for the awful curse that He placed on my body as the sign of my corruption.” The rows of hands underneath Krieg’s body were now impotent fists, curled up on the scratched wooden floor. “My task, He told me, was to cast you screaming with torment into Hell, so that all can see His order, so that others would follow my path and purge all the joker abominations from the earth.”

“You’re a sick, sick bastard, Krieg. You know that?”