Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

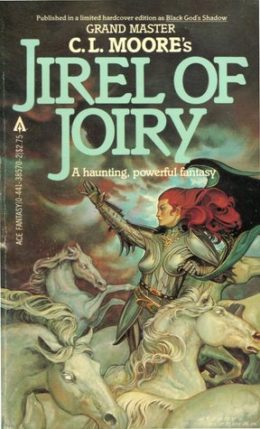

Today we’re looking at C. L. Moore’s “Black God’s Kiss,” first published in the October 1934 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

“No human travelers had worn the sides of the spiral so smooth, and she did not care to speculate on what creatures had polished it so, through what ages of passage.”

Summary

Guillaume the conqueror sits in the great hall of Joiry, looking “very splendid and very dangerous” in his spattered armor. Men-at-arms hustle in Joiry’s defeated lord, or so Guillaume thinks—when he cuts off the tall fellow’s helmet, he finds himself facing Joiry’s lady, the red-maned and yellow-eyed Jirel. Her furious curses don’t put him off as much as her “biting, sword-edge beauty” attracts. But before he can act on that attraction, Jirel wrests free from her guards; to steal her kiss, Guillaume must first subdue her himself. It’s like kissing a sword’s blade, he declares. Jirel’s not flattered, and lunges for his jugular. So much for lovemaking. Guillaume knocks her out with a single blow.

Jirel wakes in her own dungeon, heart ablaze with the driving need for vengeance on this man (however splendid) who has dared laugh at her righteous rage! She cracks her guard’s skull and steals his sword. It won’t be weapon enough, but she knows where to seek another. Together with her confessor Father Gervase, she once explored a secret place under the castle, and though that place be a very hell, she’ll search it for the means to destroy Guillaume. Gervase reluctantly gives his blessing but fears it will not avail her—there.

She creeps to the lowest dungeon and uncovers a shaft made not so much for humans as for unnaturally huge serpents. Jirel slides down its corkscrew curves, “waves of sick blurring” washing over her. The shaft is uncanny, gravity-defiant, for she knows from her previous visit that the trip back “up” will be as easy as the trip “down.”

In the lightless passage below she encounters a wild wind that raves with the “myriad voices of all lost things crying in the night.” The piteous wails bring tears even to her hardened eyes, but she pushes on until the passage expands into a subterranean world. At its threshold her crucifix-chain goes taut around her throat. Jirel lets the cross fall and gasps: gray light blooms over misty plains and far-off mountain peaks. The welcome wagon is a “ravening circle of small, slavering, blind things [that leap at her legs] with clashing teeth.” Some die “squashily” on her sword. The rest flee. Surely in a land this unholy, she’ll find the weapon she seeks.

She heads toward a distant tower of “sheeted luminance.” Good thing she runs fast as a deer in this strange place. Meadows of coarse grass give way to a swamp peopled by naked, blind-eyed women who hop like frogs. Later she’ll encounter a herd of magnificent white horses, the last of which whinnies in a man’s voice, “Julienne, Julienne!” Its despairing cry wrings her heart. The pale, wavering things in a dark hollow she never sees clearly, thank you Jesu.

The tower of fire radiates no light—it can be no earthly energy! Inside is an animate floating light that morphs into the shape of a human woman—Jirel’s own double—and invites her to enter. Jirel throws a dagger in first, which flies into its component atoms. So, yeah, she stays outside.

The Jirel-shaped light admits her intelligence. When Jirel asks for a weapon to slay Guillaume, the light muses, “You so hate him, eh?” With all her heart! The light laughs derisively, but tells Jirel to find the black temple in the lake and take the gift it offers. Then she must give that gift to Guillaume.

Falling stars lead Jirel to the lake. A bridge made of blackness like solid void arches over the star-filled waters to a temple. It houses a figure of black stone: a semi-human with one central eye, “closed as if in rapture.” It’s “sexless and strange,” crouching with outstretched head and mouth pursed for a kiss. Every line and curve in the underworld seem to converge on the figure, and that “universal focusing” compels Jirel. She presses her lips to the figure’s.

Something passes from the stone into her soul, “some frigid weight from the void, a bubble holding something unthinkably alien.” Terror drives her homeward, even if to “the press of Guillaume’s mouth and the hot arrogance of his eyes again.” Overhead the sky begins to lighten, and somehow she knows she mustn’t remain in the underworld when its unholy day dawns. Day will show her what gray night has left vague, and her mind will break.

Jirel makes the passage back just as “savage sunlight” falls on her shoulders. She reclaims her crucifix and stumbles on in merciful darkness. The “spiral, slippery way” of the shaft is as easy as she expected. In the dungeon, torchlight awaits her, and Father Gervase… and Guillaume, still splendid. Jirel’s own beauty has been dulled and fouled by the nameless things she’s seen, for the “gift” she carries is a two-edged sword that will destroy her if she doesn’t pass it on quickly.

She staggers to Guillaume and submits to his “hard, warm clasp.” Icy weight passes from her lips to his, and Jirel revives even as Guillaume’s “ruddiness” drains away. Only his eyes remain alive, tortured by the alien cold that seeps through him, carrying “some emotion never made for flesh and blood to know, some iron despair such as only an unguessable being from the gray formless void could ever have felt before.”

Guillaume drops, dead. Too late Jirel realizes why she felt “such heady violence” at the very thought of him. There can be no light in the world for her now he’s gone, and she shakes off Gervase to kneel by the corpse and hide her tears under the veil of her red hair.

What’s Cyclopean: The light-walled palace seems like it ought to be cyclopean, though Moore merely admits that “the magnitude of the thing dwarfed her to infinitesimal size.” The temple’s inhabitant is “innominate,” a word so Lovecraftian I’m shocked he ever settled for “unnameable” himself.

The Degenerate Dutch: Joiry appears to be one of the tiny kingdoms that sprung up in the wake of Rome’s retreat, but the story has—as expected, for pulp sword and sorcery—no particular objection to barbarians.

Mythos Making: The geometry below Jirel’s dungeon has corners with curves. Maybe don’t build your castle on top of a R’lyehn escape hatch?

Libronomicon: No books. If you want books, maybe don’t hang out with barbarians.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Jirel’s sanity is threatened by sunrise in the demon land, as well as by the inhuman emotion she carts home for Guillaume.

Anne’s Commentary

Not long after Howard unleashed Conan the Cimmerian in the pages of Weird Tales, C. L. Moore introduced the first lady of sword-and-sorcery, Jirel of Joiry. “Black God’s Kiss” is Jirel’s debut, which she enters in all her ferocious mailed glory and defiance, eschewing tedious backstory. The opening’s in media res with a vengeance. Guillaume has already conquered Joiry, evidently without informing himself beforehand that its lord is a lady. So, nice surprise for him, mmm, maybe. It’s unclear whether Jirel knows much about Guillaume before she “greets” him in her hall. If they’re total strangers, Moore serves us one serious plateful of insta-love here, slapped down on the fictive board with a highly spiced side of insta-hate on Jirel’s part.

Wherever we turn, we meet that attraction-repulsion paradigm, don’t we?

At first I wasn’t swallowing that the truly kickass Jirel would first-kiss moon over her conqueror, however splendid and dangerous and white-toothed and black-bearded he might be. On reflection, and after rereading the story, I’m good with the twist. Guillaume’s not just any conqueror, after all. He’s an embodiment of the Life-force itself, expansive and ruddy, imperious and lusty and as good-humored a tyrant as you could ever meet on a fine, post-battle morning resonant with the caws of feasting ravens. As his female counterpart, Jirel can’t help but respond to his advances. As his female counterpart, she can’t help but resent and reject him. Hers, too, is a warrior’s soul, as Guillaume himself recognizes and admires. Too bad he lapses into alpha-male sweet talk, calling Jirel his “pretty one,” as if she were just another spoil of war to ravish. Big mistake. Jirel is not “innocent of the ways of light loving,” but no way is she going to be “any man’s fancy for a night or two.” She’ll go to hell first.

And so she does.

This isn’t any standard Christian hell, though, which is probably why Father Gervase fears it so much. Nor do I think Jirel’s crucifix has any real power in the world beneath her castle. The cross shrinks from entering the place. It, and the faith it symbolizes, can only blind its wearer to the truth of stranger dimensions; a determined adventurer like Jirel can shed faith and blinders at need, take them up again in desperation, yet still carry the truth home with her. What gorgeously terrifying strange dimensions these are, too, with their echoes of Lovecraft’s OTHER spheres.

The hidden shaft to the underworld wasn’t designed for humans but for something rather snakier. That brings to mind the tunnels in “Nameless City,” made and used by lizard-men. Also reminiscent of “Nameless City” is the wind freighted with uncanny voices. Other echoes resound from Lovecraft’s Dreamlands, often reached through twisty tunnels and rife with small but toothy horrors with a sometimes interest in human flesh. Moore’s local god is much like the Dreamlands version of Nyarlathotep, sardonic and fond of multiple avatars, from the purely energetic to the imitative to the only seemingly inanimate.

Lovecrafty, too, is Jirel’s impression that she’s entered of a place where Earth’s physical laws don’t apply, an alien place with alien norms, far weirder than any subterranean realm of the hoofed and horned demons of Christian lore. Up and down mean nothing in the spiraling shaft, where some unknown but “inexorable process of nature” prevails. Whatever energy or force makes up the round tower is self-contained, emitting no light. The lake temple and its bridge are composed of something Jirel can only conceptualize as the blackness of void, made visible only by what surrounds it. Lines and angles and curves hold “magic,” all leading to (or from) a god beyond human comprehension (however it mimics human form). And in classic Lovecraft fashion, Jirel realizes (almost) too late that she’s wandered into a region so ELDRITCH that to comprehend it in the light of day would drive her insane.

Less Lovecrafty is the implication that the lost souls who wander “Black God’s” underworld were delivered there by bad love rather than curiosity or longing for place. We have women turned into “frogs,” presumably by kissing the wrong princes. We have men transformed into horses who scream the names of ladies lost to them. We have pale wavering forms Jirel doesn’t even want to see clearly, and those sticky snapping little horrors grow dangerous in sticky snapping accumulation, like the little hurts and lies and jealousies that can destroy love. And the god of it all mirrors supplicants, or offers them poisonous and possessive kisses.

Not exactly a honeymoon paradise. In fact, I don’t plan to schedule any vacations in Black God territory.

Set the finale of “Black God’s Kiss” to Wagner’s Liebestod. Moore’s now two-for-two in our blog for fatal attractions. Mess with Shambleau and lose your soul. Mess with promiscuous puckered gods and lose your soul, unless you can pass the curse on with a kiss.

Man, is it me, or do love and sex get scarier with every reread lately?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Dark gods below the waves, but I hate the ending of this story.

If you find yourself stuck in C. L. Moore country, even consensual romance is a terrible idea. You’re unlikely to survive a first date with Northwest Smith, and Jirel trails nasty fates in her wake. Warriors forcing favors from newly conquered barbarian heroines had better just make their peace with the universe.

Did Moore’s low opinion of romance come from personal experience? Or did she just have a fine appreciation for femmes et hommes fatales? Either way, my most charitable interpretation of this ending (which I hate) is that for Moore, romance is such an intrinsically terrible idea that affection is naturally given to the worst possible choice available. And Guillaume is such a terrible, terrible choice. If my hormones rose up and bit me over a dude who couldn’t figure out the basics of consent, and who’d left blood all over my floor besides, I’d be grateful to any demon who put Bad Idea Conan permanently and fatally out of reach. Did I mention my feelings about this ending?

However, there’s a lot of story before that repugnant end, and a lot to like about it. “Black God’s Kiss” melds Howard P. L. and R. Howard to excellent effect—sword-and-sorcery limned with the semi-scientific awe of cosmic horror. Plus girls with swords! (Jirel gets forgiven a lot—like sobbing over Bad Idea Dude—by virtue of being First.) Normally my eyes start to roll when cosmic horror is vulnerable to itty cross pendants. Here it works as a first indication that the reasonable-appearing landscape is truly and incomprehensibly inhuman. Jirel has to cast aside her safe and familiar Christian worldview to perceive it—at which point that worldview’s no protection at all.

And it’s the inhuman landscape that’s the star here. There are creepy creatures abounding, but what’s truly and awe-inspiringly cosmic is the geometry of the place. Starting with that twisting passage down from the dungeons and all their implied questions. What made them? Are they still there? Do they come up to party in Jirel’s basement on a regular basis? Then the palace made of light, that doesn’t act quite as light ought, and has an unfortunate tendency to disintegrate visitors. The near-invisible bridge, vertiginous just to read about. The lake, and the compulsive curves at the center. The whole story works by Rule of Cool, in the best possible pulpy tradition.

And it’s not merely a disinterested tour of Other Dimensions, but fraught with melodramatic emotion (again in the best possible pulpy tradition). We have, at the end, the intriguing idea of an emotion so alien that humans can’t bear it. Incomprehensible creatures from beyond the laws we know are a common staple—but usually their incomprehensible emotions are safely ensconced in their own incomprehensible minds (if sometimes awkwardly forced into human bodies). In this case the emotion takes on independent existence, infecting anyone foolhardy enough to kiss things they really, really shouldn’t.

Yet this unnameable emotion is foreshadowed by very human emotions: the foreign landscape is interspersed with moments that draw extremely nameable (if, one suspects, relatively unfamiliar) moments of tear-struck pity from Jirel. Which of course, in turn, foreshadow Jirel’s tear-struck, inexplicable, and altogether human emotion at the end of the story. (Tell us again how you feel about that, Ruthanna.)

Next week, Lovecraft and Lumley’s “Diary of Alonzo Typer” shows that psychical research is a thankless area of study.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.