They say it’s not the fall that kills you—for Josette Dupre, the Corps’ first female airship captain, it might just be a bullet in the back.

And yet somehow author Robyn Bennis always finds a way to make that kind of situation funny.

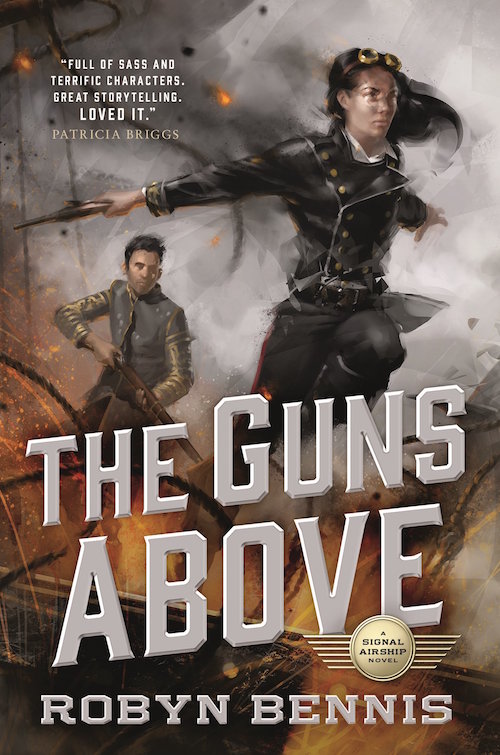

Below is just one example from her forthcoming military fantasy adventure novel The Guns Above—out on May 2nd from Tor Books—which chronicles Dupre’s struggle to achieve victory despite her doubting crew, her untested airship, and the shameless Lord Bernat, a gambling flirt who is actively trying to undermine her command.

The crew adjusted the rigging, brought water and fire blankets forward, readied the bref guns, secured the small-arms racks to the rails, and loaded the rifles.

Bernat wondered if any of them questioned Dupre’s feeble pantomime of a brave captain, and suspected they didn’t. They hadn’t seen the real Dupre, hiding in the bow, fretting until she turned red. The crew, no doubt, thought she’d been planning this all along, that her hesitation was part of some elaborate stratagem. He would have to mention that in his letter. Perhaps he’d add something about “permitting the deceit and vanity natural to her sex to rule over her other faculties, such as they are.”

As he was contemplating this, the woman herself appeared before him and shoved a rifle into his hands. “Here. Make yourself useful and help the loader.”

Bernat looked at the crewman who was busy loading rifles, then at Josette. He was thoroughly confused.

She sighed and spoke very slowly. “Load this rifle, please.”

He took the rifle, but could only stare at it. “And how does one go about doing that?”

She narrowed her eyes. “You must be joking.”

“At the palace, we have someone to handle these sorts of trivialities.”

She snatched the rifle back. “If he can’t find any other utility, my lord will perhaps lower himself to firing a shot or two at the enemy?”

“That sounds delightful,” Bernat said. He didn’t relish the thought of going into battle, but it seemed he had no choice, so he might as well kill a few Vins while he was at it. It would, at least, give him something to brag about.

The ship drove on, gaining altitude so quickly the change caused a pain in his ears.

“Passing through five thousand,” Corporal Lupien said. Bernat was beginning to suspect the men and women of the signal corps simply enjoyed making pointless announcements.

Martel, posted along the forward rail of the hurricane deck, suddenly put his telescope to his eye and cried out, “Enemy sighted! Two points starboard at about four thousand.”

Bernat looked in the direction he was pointing and, by squinting, could barely see a speck in the sky. “Tallyho!” he cried. But when he looked about, only blank stares met his enthusiastic grin.

“Tally-what?” Martel asked.

“It’s what one says on a fox hunt, when the quarry is sighted.” His grin diminished. “You know, ‘tallyho!’ I thought everyone knew that.”

“Come to one hundred and twenty degrees on the compass,” Dupre said. The bitch was ignoring him.

Lupien made a few turns on the wheel. The ship came about, but not far enough to point directly at the enemy. Bernat asked Martel, “We aren’t going straight for them?”

“Cap’n wants to keep us between them and the sun,” he said, handing the telescope to Bernat. After a bit of fumbling, Bernat found the enemy ship in the glass.

He’d been expecting something smaller, perhaps some weathered little blimp covered in patches. But the thing Bernat saw through the telescope was an airship, comparable in size to Mistral and bristling with guns.

“She has a fierce broadside,” Bernat said.

“Three per side,” Martel said. “But they’re only swivel guns.”

“What a comfort,” Bernat said. When he looked into the telescope again, the ship was turning toward them. “They’ve seen us! They’re attacking!”

Martel snatched the telescope back and looked out. “No, no,” he said. “They’re only turning to keep near cloud cover, but the weather isn’t doing them any favors today.” Indeed, the mottled cloud cover had been shriveling up all afternoon. The cloud bank near which the enemy lingered was one of the largest in the sky, but only a few miles wide at that.

“Range?” Dupre asked. “I make it five miles.”

It seemed to Bernat that an hour or more had passed before Martel called the range at two miles. Consulting his pocket watch, however, he found that the elapsed time had only been four minutes.

Dupre nodded and ordered, “Crew to stations. Mr. Martel, please send a bird to Arle with the following message: ‘From Mistral: have engaged Vin scout over Durum.’ ”

Lieutenant Martel patted Bernat on the back, in a most uncomfortably familiar manner for a commoner. “Don’t worry, my lord. Everyone’s a little nervous, their first time.” He trotted up the companionway ladder and disappeared into the keel.

The gun crews stood in their places next to the cannons, except for Corne, who had found Bernat standing in his spot and didn’t know what to do about it. Bernat had sympathy, but not enough to move. If Corne wanted the spot so badly, he should have gotten there earlier. Martel came down carrying a pigeon. He released it over the rail, then went back up the companionway to take station aft.

They were on the outskirts of Durum now, passing over farmland and old, flooded quarries. The Vinzhalian ship hovered below and to the east, just beyond the old stone wall that surrounded the town. Just south of the town was Durum’s aerial signal base. Its airship shed was a pitiful little thing compared to Arle’s, but it was still the largest building in sight, and would have been the tallest if not for a rather excessive spire on the town’s pagoda, most likely added to keep the shed from being taller.

Bernat saw something fall from the enemy ship. He thought they must be bombing the town, until Kember said, “Scout dropping ballast! Sandbags… and now water. They’re turning away.” She put the telescope to her eye. “And they’ve released a bird. It’s heading east, toward Vinzhalia.”

“Range?”

“To the bird, sir?”

“To the scout ship, Ensign.”

“Over a mile, I’d say. A mile and a half. No, maybe less than that. A mile and a quarter. Maybe a little over a mile and a quarter.” Kember’s voice had a noticeable tremor in it.

“Thank you, Ensign,” Dupre said.

The girl winced. Bernat deigned to pat her on the shoulder. “Don’t worry. I have it on good authority that everyone’s nervous their first time.” They were close enough now that, even without a telescope, he could see a port opening in the tail of the enemy ship. It was suddenly lit by a brilliant light, from which emerged some small object, streaking toward them and trailing smoke. “Good God,” he screamed. “They’re shooting at us!” Only then did the shriek of the rocket reach his ears.

Behind him, Dupre sighed and said, “It would be more remarkable if they weren’t, Lord Hinkal.”

Look for more thrilling excerpts from The Guns Above!

I disagree, as “tallyho” is what fighter jocks say when they’ve sighted the enemy and this is technically their air force.