Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

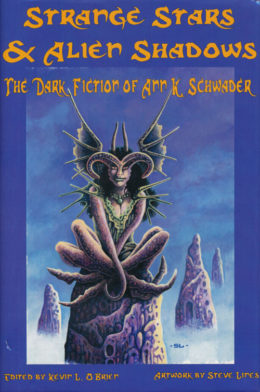

Today we’re looking at Ann K. Schwader’s “Objects From the Gilman-Waite Collection,” first published in 2003 in Strange Stars and Alien Shadows: The Dark Fiction of Ann K. Schwader. Spoilers ahead.

“What he had taken at first for arabesques now appeared as lithe, androgynous figures. The cast of their features disturbed him, though it took a few moments to see why. They echoed the armlet’s aquatic flora and fauna: bulging eyes and piscine faces, gill-slitted throats and shimmering suggestions of scales on shoulder and thigh.”

Summary

Traveling on business, narrator Wayland spots an exhibition poster picturing gold and coral figures of an “ethereal moon-white luster.” They’re some of the Objects from the Gilman-Waite Collection, Unique Cultural Art-forms of Pohnpei, sponsored by the Manuxet Seafood Corporation. Their design is oddly familiar. Free for the afternoon, he goes into the museum.

The Gilman-Waite collection resides in a dark, narrow room abuzz with the hum of a dehumidifier. It’s needed, for though the rest of the museum’s bone-dry, this room feels damp, down to the unpleasantly spongy carpet. He first examines an armlet featuring a seascape peopled by androgynous figures with piscine faces, webbed digits and scales. Its coral “embellishment” disturbs him—it’s the color of pallid, blue-veined flesh, and it seems to writhe in its gold setting as if tormented by the metallic clasp. Plus the woman who could wear the armlet had to have pretty hefty biceps.

Which thought triggers memory, of “slick cold skin, almost slipping from his grasp as she struggled.”

As if cued by the memory, a docent appears. She shrugs off his question about the collection’s exact origin. The exhibit’s intent is “to help viewers appreciate [the Objects] purely as art.” Her wide dark eyes remind him of a girl he met “back East” and escorted to a drunken collegiate party. But that girl would have aged fifteen years since their disastrous “date.”

Wayland moves on to an “impossible” tiara, too high and elliptical for a human head. The docent tells him to let his eyes follow the upward flow of the piece—”that makes all the difference.” Indeed, when he obeys, its stylized curves coalesce into a grotesque entity from which he turns away, remembering again the long-ago girl and his drunken impression that she was no ignorant townie, no mere ignorant and easy score, but a being “ancient and cunning, inhuman.”

He raped her anyway.

As Wayland moves from case to case, the collection oppresses him with “how relentlessly aquatic it was, ebbing and pulsing in an ageless rhythm which was subtly wrong. Offbeat from any human rhythm, even that of his heart.” Is the air getting damper, the carpet clinging to his feet? He doesn’t like the way the docent’s face emerges from the dark, like a swimmer’s surfacing from dark water. The long-ago girl had too many tiny, sharp teeth, and she laughed at him silently even as “he did what he’d done in anger.”

He tries to leave, but the docent steers him toward the last and largest piece, set apart in a tunnel-like alcove. The alcove carpet smells like vegetable decay, like something dead on a beach. Lights like candles flickering underwater illuminate a massive gold and coral piece. It must be hugely valuable, but no case protects it, and the docent tells him it’s all right to touch this masterpiece. In fact, he must, to fully appreciate it.

Wayland doesn’t want to touch any part of the scene of ritual slaughter, not the naked female celebrants, not their inhuman goddess with Her ropy tresses and scythe-like claws. Yet long-ago emotion swamps him: “desire and rage and disgust…the strong hot undertow of temptation.” The docent urges him on, her voice that girl’s voice, the voice that whispered afterward, “I’ll see you again.”

He recoils, only to twist his ankle in the sodden carpet and fall backwards, into the gold and coral figure. No, he doesn’t just fall—he flows toward its carven sacrificial slab. His flesh undergoes a “sea-change” to pallid, blue-veined coral, living and feeling coral fettered to the slab under the celebrant-priestess and her gutting hook. The other celebrants surround him, to circle “as the stars must… forever and forever… towards the rightness of Her dead and dreaming lord’s return.”

Her being Mother Hydra, as the docent cries out Her name.

The gutting hook, fashioned after one of Hydra’s own claws, does not long delay its fall….

What’s Cyclopean: The twining figures of the Objects are “suggestive and malignant.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Wayland doesn’t like rural towns, but he sure seems to end up there a lot. Not too fond of girls, either, but…

Mythos Making: Gilman and Waite should be familiar names to anyone who follows the mythos. As should Mother Hydra.

Libronomicon: This story features some truly terrible exhibit labels. But then, informativeness isn’t really the point.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Drinking enough to interfere with your memory carries risks—some more esoteric than others.

Anne’s Commentary

Since I always comb consignment and antique stores in hopes of finding a stray piece of Innsmouth jewelry, I was eager to read “Objects from the Gilman-Waite Collection.” Everyone knows that the Gilmans and Waites hold the finest trove of Y’ha-nthlei and R’lyeh gold after, of course, the Marshes. It’s also nice to start National Poetry Month with Ann K. Schwader, a poet whose collections include Dark Energies, Twisted in Dream and In Yaddith Time.

The lush and precise language of “Objects” is poetry “decompressed” to fit not-at-all-purple prose, which in turn suits the not-insensible but self-centered point-of-view character. That “prop” of pallid, veined, and seemingly animate coral is so striking and central I wonder if it wasn’t the initium for this story. Marine imagery dominates once we enter the grotto-like hall of the Objects, with its moisture-laden air, shifting watery lights and a carpet as damp and clingy as seaweed (and I note with admiration how Schwader conveys this sensation without ever writing the word “seaweed.” Well, until she gets to Mother Hydra herself, whose arms are as twisted and supple as kelp, and there it’s an unexpected comparison, hence the sweeter.)

In this story, my favorite allusion is not to Mythosian canon but to Ariel’s song from The Tempest. When Wayland’s “meat” turns to coral, it’s undergoing a “sea-change.” As in:

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Yes! What better way to describe Deep One metamorphosis than “sea-change,” and into something strange at least. Also something rich, we Deep One apologists would say. I bet Shakespeare visited England’s Innsmouth from time to time and threw back a few pints of Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar with its friendly pub-hoppers.

Pohnpei, supposed source of the Gilman-Waite collection, is the largest island in the Federated States of Micronesia. It’s also the “Ponape” that Captain Obed Marsh visited, with cosmic consequences for his native Innsmouth. Fittingly, Pohnpei translates to “upon a stone altar.”

Or an altar in effigy, and in lustrous white gold.

All right, then, on to the sacrificial platform. Metaphorically speaking, since none of us is an arrogant jerk like Wayland. My question is whether “Objects” is really a straightforward supernatural revenge tale. Wayland did something BAD. Because he’s an arrogant jerk. The victim doesn’t forget or forgive, nor does she have to. Because she’s way more than she appeared to be, with the ability to wait a long time and then, out of the blue, to hit back in ironically suitable fashion. Simple moral: Don’t mess with girls with gills. Or any girls, really, because it’s NOT RIGHT. Also, because their gills might not be showing yet, jerk.

I’m thinking, however, we’re not supposed to view Wayland just as Evil Sociopath and the Innsmouth girl just as Innocent Victim. No denying Wayland’s attitude toward women is unsavory: Due to the “yammering of his hormones,” he sorts females by sexual attractiveness and/or availability. The Innsmouth girl wasn’t attractive, but hell, she was THERE and drunk and backed into a convenient bedroom. Worse than an ugly woman? One who CHALLENGES Wayland. Which was another mark against the Innsmouth girl, who fought back when assaulted, the nerve, pissed him off. Does that make him a serial rapist? Maybe not actually, but he’s got some of the psychological makings of one.

We don’t like Wayland, but does he deserve sea-change into an eternal human-coral sacrifice? I’ve scraped up a little sympathy for him, not because of his merits but because Innsmouth Girl’s an even more complex character, or even a complex of characters. Even drunk, Wayland realizes she’s no sweet little townie for single usage. The girl has muscles under her slick cold skin. Must’ve scaled a lot of fish and shucked a lot of oysters over at Manuxet Seafood! She almost fights him off; knowing her nature as we readers do, we may wonder why just “almost.” Her eyes are extraordinary, too, “wider than human and darker than night ocean, boring into his soul.” He tastes the ocean on her lips, primal salt. However young her body feels, looking into those night-ocean eyes he sees something “ancient and cunning.” And what’s with her barracuda teeth, and her silent laugh, and that “I’ll see you again” as he leaves?

If the docent is the Innsmouth girl, she hasn’t aged. Yet by the end, Wayland’s sure she is the same one.

Lots is not what it seems, methinks. Why should vengeance fall on Wayland in some (Colorado?) “cow-town,” far from the site of his crime? Why does the exhibition happen to be there at the same time he is? Is it there at all, for anyone but Wayland? He has to search for the display room, barely labeled even though there was a fancy poster out front. The room is narrow and yet—expandable? At one point he thinks it’s larger than he observed at first, and the before-unnoticed alcove with the masterpiece is longer, a veritable tunnel. I call the whole Gilman-Waite Collection one of those lovely interdimensional places meant only for particular eyes.

As for the Innsmouth girl, I call her either an avatar of Mother Hydra, the ancient and cunning One, or an acolyte of Hers, temporarily possessed by Mother, either in response to the outrage being committed on her or – Or even sent with the prior intention of marking Wayland for future harvest via ritual union?

Guys. Girls. You have got to take warning from “Objects” and other recent stories, from “Furies from Boras” to “The Low Dark Edge of Life” to “The Black God’s Kiss.” And, going back to Howard, from “Arthur Jermyn” and “Lurking Fear” and “Dunwich Horror” and “Thing on the Doorstep” and “Medusa’s Coil” and “Shadow Over Innsmouth” and “The Horror at Red Hook.” Sex is dangerous. Especially weird-fictional sex. Especially coercive weird-fictional sex.

Celibacy could be an option for wanderers in eldritch territory. Just saying.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Museums are liminal. They’re places of preservation, discovery, and knowledge, wonder, and of research that fits isolated “objects” back into their full contexts so that everyone can understand them. But they can also be where we bring the strange, the exotic, the distant—to put it in carefully demarcated boxes, make it safe, fit it neatly into our own lives for a carefully calibrated dose of curiosity.

But we don’t really want them to be safe. From “Out of the Aeons” to Night at the Museum, we thrill at the idea that exhibits might be something more. Might step down off their safe pedestals and become something rich and dangerous.

The Gilman-Waite Objects don’t seem promising at first for this type of resurrection. After all, the unnamed rural museum seems shockingly uninterested in where they come from or what rituals they’re intended to illustrate. My first thought as a reader: these things are stolen, and being kept away from someone. Why else would Innsmouth jewelry be sitting in a desert town, warded by a dehumidifier with an Ominous Warning, unless someone dependent on moisture is eager to get in? Then the docent assures Wayland that the Objects have been stripped of context so they can be more fully appreciated as art… obviously someone’s trying to erase their history.

But no—it turns out that rather than erasing history, the docent is trying to mask it. IT’S A TRAP! One that Wayland appears to richly deserve. Soon he’ll have all the historical context anyone could ask for.

“Objects” does a bunch of things I don’t always like, and yet it totally works for me. The Deep Ones are a good balance of comprehensibly sympathetic and inhumanly creepy, as liminal as the museum itself. The mundanely creepy jerk of a narrator remains bearable, because most of his description focuses on fascinating sensory detail. The creepster-gets-comeuppance plot is spandreled with clever wordplay and the inspirational metalwork of Y’ha-nthlei.

Oh, that Deep One jewelry! It’s one of the more intriguing details in “Shadow Out of Innsmouth.” In the midst of rumored sacrifice and scandal, we learn that these shuffling fish-frog creatures work gold into exquisite sculpture and necklaces, complex with symbolic figuring. Think of that weight of gold around your throat, of running your fingers over the bas relief miniatures, imagining the mysteries of the deep… Schwader’s Objects are described repeatedly in oceanic terms: eyes and minds are drawn into their flow. The fleshlike coral adds another note of creepy intrigue. The troubling geometry echoes that of R’lyeh, Tindalos, and the Witch House.

We get only minimal detail about what Wayland did to earn Mother Hydra’s interest, but it’s sufficient to determine that he earned it. Blind date with a Deep One hybrid in Arkham, made blind-er by way too much alcohol. Wayland figures the alcohol will get him an easy lay—easy, and easy to dismiss, appear to be his primary criteria for female company. But beer goggles prove insufficient to hide his date’s batrachian nature. She challenges him—merely by existing and not being what she seemed? By knowing Cosmic Secrets that he doesn’t? He forces himself on her, and she promises to see him again.

And then… she takes years to gather her forces, finally arranging to entrap him in a museum exhibit/ritual altar surrounded by desert, on the far side of the continent. A reasonable response, sure, but seems a bit baroque. Never let it be said that Innsmouth girls aren’t a determined lot.

National Poetry Month has its own eldritch glories; join us next week for Duane W. Rimel’s “Dreams of Yith.” You can find it in the Second Cthulhu Mythos Megapack, or in your local branch of the Archives. (And this week, Ruthanna’s novel Winter Tide is finally out! The Reread’s current obsession with Deep Ones and Yithians may not be a complete coincidence.)

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” is now available from the Tor.com imprint! Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

One thing that goes unmentioned here is the relevance to Lovecraft’s xenophobia. It seems that a lot of the energy of Lovecraft’s dread and disgust stems from his real-life racism and religious prejudice (which were quite acceptable to the New England society of his time). His Arabic names, now more than ever, reveal this streak in his horror. The villagers at Innsmouth are simply caricatures of bi-racial people, after all. They start off as human, but inevitably will become fully fish-like Deep Ones; just a metaphor for the deepest fears of a racist. Schwader extends this to sexism. Lovecraft couldn’t seem to handle introducing femininity or female characters into his stories as all, but in Wayland we get the same fear of the “other” that Lovecraft conveyed in his stories. Shwader gets into the head of such a man and confronts him with his worst fears. It’s a lot of fun.

One of the things that always jumps out at me is that in Lovecraft’s letters, he describes my ancestors (Jewish immigrants in New York) in about the same terms he uses for the Deep Ones! I play with that connection a lot in my own writing, though I didn’t think it was any part of Schwader’s focus. Which is fine–Lovecraft’s misanthropic prejudices were broad enough that you can use his monsters to talk about any given subset of them.

I started the reread with the impression that Lovecraft never includes female characters, and have been surprised by how many show up and even occasionally get something done (albeit mostly in the Hazel Heald collaborations). His work is unquestionably misogynist, but when he hasn’t just gotten divorced he seems more confused by women (What are they? Why would you talk to one?) than anything else. Relative to other authors of his time, my current opinion is that his racism looms much larger than normal and his sexism actually a bit smaller, simply by virtue of the relative levels of obsessive thought. That is, Lovecraft spent more time thinking about scary scary foreigners, and less thinking about women, than most white men of this time. Make of that what you will.

Anyway, welcome to the Reread! I promise much crunchy discussion of xenophobia, along with attempts to determine exactly how many Necronomicons are really out there, and dissection of the real distinction between cyclopean and gambreled architecture

As a writer of museum exhibit labels, I really want to read those “truly terrible” ones.

As an overworked paleontology museum docent with four rowdy school groups to deal with this week, I’m glad I don’t have the ability to turn people into exhibits, i.e. fossils.

As a wannabe aquatic humanoid of Jewsh descent, I have mixed feelings about that comparison by Lovecraft.

Now I’m imagining the song “Cape Cod Girls” rewritten for Innsmouth. Has someone already done that? I expect so, but I’m afraid to look.

Your mention of Wayland “sorting females” reminds me of the Witcher Saga describing in detail how Dandelion mentally rates any woman’s “likeability” based solely (iirc) on her willingness to have sex with him. It’s probably a common thing, but gross when spelled out.

If by “mess with” you mean rape, I intend to never mess with gilled girls or anyone else. But I wouldn’t turn down a date with a Deep One hybrid of any gender, though I’d rather alcohol were not involved because I hate the taste.

*sigh*

I would think a dehumidifier would be exactly the wrong thing for these pieces, especially in the desert. Given the moistness of the carpet and all, that may have been a bit of misdirection, though.

The thing that always puzzles me the most about Lovecraft’s antisemitism is his utter inability to move from the particular to the general. He had a rather large number of Jewish friends and correspondents, not to mention his wife, he seems to have gotten along well with them and was rather close to Samuel Loveman, and yet never made the logical leap.

If we’re doing poetry this month, we should definitely do some Frank Belknap Long. The Megapack with next week’s reading also has his “When Chaugnar Wakes”, which IIRC is pretty mythos related. If the cat weren’t draped over my left wrist, I could pull down the slim volume of his poetry that Arkham House put out and see if there are any other candidates. Maybe later.

ETA: While reading up for the Galactic Journey, I spotted a letter from Muriel Eddy in the May 1962 Fantastic. She was commenting on the magazine having run “The Shadow Out of Space” in February and noted the 25th anniversary of his death. She mentioned that she and her husband often visited the grave and actually gave out her address, asking to hear from HPL fans.

For some reason completely beyond my understanding, this story reminded me of another I read once about a guy who is attacked (and intimately invaded) by a potato.

It’s creepier than it sounds.

I started the reread with the impression that Lovecraft never includes female characters, and have been surprised by how many show up and even occasionally get something done (albeit mostly in the Hazel Heald collaborations). His work is unquestionably misogynist, but when he hasn’t just gotten divorced he seems more confused by women (What are they? Why would you talk to one?) than anything else.

The majority of the Deep One characters in Lovecraft’s stories are female, and the fact that they are the spouses of the ‘limb o’ Satan’ Marsh types indicates that they value consensual, committed relationships… they even let old Zadok keep his head on his shoulders when he refused to become a suitor. It’s no wonder they come across as sympathetic to modern readers. Poor Asenath Waite, done in by her evil human father!

It’s weird how so many of the tropes regarding Deep Ones morphed into the ‘OMG, they’re after our wimmins’ variety, when it is so at odds with the original material.

For some reason completely beyond my understanding, this story reminded me of another I read once about a guy who is attacked (and intimately invaded) by a potato.

Was it in the Telegraph?

Ms. Schwader is most highly regarded as the leading poet of weird fiction, but I always have enjoyed her fiction, She is sadly not very prolific. Of some interest (tangentially) to this story is the wonderful book The Starry Wisdom Catalogue from PS Publishing, edited by Nate Pedersen. It is a catalogue for a rare book auction from 1877 that for some reason never took place. Each ‘scholar’ was assigned a tome, and provided a description of the physical volume, with detailed notes about its provenance or contents. Ms. Schwader’s own contribution was a delight. What makes this even more connected is that a companion volume is planned, The Dagon Collection. This is planned to be a catalogue of mythosy objects instead of tomes. I was hoping Ms. Schwader would include one of these items, like the sacrificial knife, as her entry.

JOSHI, S. T. – Introduction

ANIOLOWSKI, Scott David – Massa di Requiem per Shuggay

BARRASS, Glynn – The Book of Azathoth

BERGLUND, Edward P. – Cultus Maleficarum

BIRD, Allyson – The Book of Karnak

BRENTS, Scott – Lewis Carroll / Charles Dodgson Letter

BULLINGTON, Jesse – Il Tomo della Biocca

CAMPBELL, Ramsey – The Revelations of Glaaki

CARDIN, Matt – The Daemonolorum

CHAMBERS, S. J. – Remnants of Lost Empires

CISCO, Michael – Liber Ivonis

CUINN, Carrie – Image du Monde

FILES, Gemma – The Testament of Carnamagos

GAVIN, Richard – De Masticatione Mortuorum in Tumulis

HANSON, Christopher – The Pnakotic Manuscripts

HARMS, Daniel – The Book of Dzyan

JONES, Stephen Graham – The Ssathaat Scriptures

LANGAN, John – Les Mystères du Ver

LEMAN, Andrew – Practise of Chymicall and Hermetickall Physicke

LLEWELLYN, Livia – Las Reglas de Ruina

MAMATAS, Nick – The Black Book of the Skull

MORENO-GARCIA, Silvia – El Culto de los Muertos

MORRIS, Edward – The Book of Invaders

NICOLAY, Scott – The Ponape Scripture

PRICE, Robert M. – The Book of Iod

PUGMIRE, W. H. – The Sesqua Valley Grimoire

PULVER, Joe – The King in Yellow

RAWLIK, Pete – The Qanoon-e-Islam

SATYAMURTHY, Jayaprakash – The Chhaya Rituals

SCHWADER, Ann K – The Black Rites

SCHWEITZER, Darrell – The Nameless Tome

SPRIGGS, Robin – The Dhol Chants

STRANTZAS, Simon – The Black Tome of Alsophocus

TANZER, Molly – Hieron Aigypton

TAYLOR, Keith – The Book of Thoth

TIDBECK, Karin – The Cultes des Goules

TYSON, Donald – Liber Damnatus

VALENTINE, Genevieve – The Seven Cryptical Books of Hsan

WALLACE, Kali – The Tablets of Nhing

WARREN, Kaaron – The Book of Climbing Lights

WEBB, Don – The Black Sutra

WELLS, Jeff – Observations on the Several Parts of Africa

WILSON, F. Paul – Unaussprechlichen Kulten

@@@@@ Kirth Girthsome, #7: No, this was a short story in a horror anthology, though for the life of me I can’t remember what anthology or when and where I read it. It starts out with the guy discovering an extremely decayed “Mr. Potato Head” in a closet and just goes downhill from there.

Why the potato is alive (and homicidal), I don’t know. Maybe the fermentation process caused it to develop sentience? I don’t think even the author knows. But for a piece of horror fiction where the only “villain” is a decaying tuber, it works better than you’d think it would, mostly for the body horror aspect at the end when the potato “seeks vengeance” or whatever it thinks it’s doing (it’s a freaking potato, so who really knows?).