Sound doesn’t travel in a vacuum. Space, then, is quiet. A place where small actions can have large consequences…

This isn’t usually the mood we see in space opera, though, is it? Normally space opera is operatic in the grand sense: noisy, colourful, full of sound and fury. But it’s interesting to look at novels that aren’t flashy in this way—that are quiet, and in many ways feel domestic, enclosed—and yet still feel like space opera. Is it the trappings of space opera’s setting—starships, space stations, aliens, peculiarly advanced technologies and faster than light travel—that make something feel like space opera, even when the opera part is domestic, constrained, brought within bounded space, where the emotional arcs that the stories focus on are quietly intimate ones?

Sometimes I think so. On the other hand, sometimes I think that the bounded intimacy, the enclosure, can be as operatic as the grandest story of clashing armies.

Let’s look at three potential examples of this genre of… let’s call it domestic space opera? Or perhaps intimate space opera is a better term. I’m thinking here of C.J. Cherryh’s Foreigner series, now up to twenty volumes, which are (in large part) set on a planet shared by the (native) atevi and the (alien, incoming) humans, and which focus on the personal and political relationships of Bren Cameron, who is the link between these very different cultures; of Aliette de Bodard’s pair of novellas in her Xuya continuity, On A Red Station, Drifting and Citadel of Weeping Pearls, which each in their separate ways focus on politics, and relationships, and family, and family relationships; and Becky Chambers’ (slightly) more traditionally shaped The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet and A Closed and Common Orbit, which each concentrate in their own ways on found families, built families, communities, and the importance of compassion, empathy, and respect for other people’s autonomy and choices in moving through the world.

Of these, Becky Chambers’ novels look more like what we expect from space opera, being set in space or touching on a number of different planets. But the thematic and emotional focuses of both these novels takes place in enclosed settings: they are primarily interested in the insides of people, and in their relationships, rather than in political or military changes, or in thrilling derring-do. The derring-do is present, at times, but the books are more interested in what the derring-do says about the people than in action for the sake of thrilling tension and adventure.

Both Aliette de Bodard’s On A Red Station, Drifting and Citadel of Weeping Pearls and C.J. Cherryh’s Foreigner series are more overtly political. Imperial politics are as much part of the background of On A Red Station, Drifting as family politics are part of the foreground, while in Citadel of Weeping Pearls, imperial politics and family politics become, essentially, the same thing. The emotional connections between individuals, and their different ways of dealing with events—with conflict, with tradition, with love and grief and fear—are the lenses through which these novellas deal with strife, exile, war, and strange science.

De Bodard’s universe is glitteringly science-fictional, in contrast to the more prosaic technology of Cherryh’s (and Cherryh’s human culture, too, is more conventionally drawn in a direct line from white 20th century America), but in the Foreigner series as well, the personal is political, for Bren Cameron’s personal relationships with the atevi—who think very differently to humans—are the hinges from which the narrative swings. And Bren’s actions take place generally on the small scale: in meeting-rooms, over tea, in forging new personal relationships around which political negotiations can take place.

Yet the operatic element—the intensity of emotion and of significance—still comes to the fore in all of these stories, for all the ways in which they take place in intimate settings and concern, often, small acts. It is this reaching for the high pitch of intensity, albeit in small and sometimes domestic contexts (and whether always successful or not), that makes them space opera, I think.

There is enough emotional scope within one single person’s life and relationships to cover any artist’s canvas in furious colour. And there’s something faintly radical about treating an individual in quieter settings as just as worthy and interesting a subject as the clash of empires…

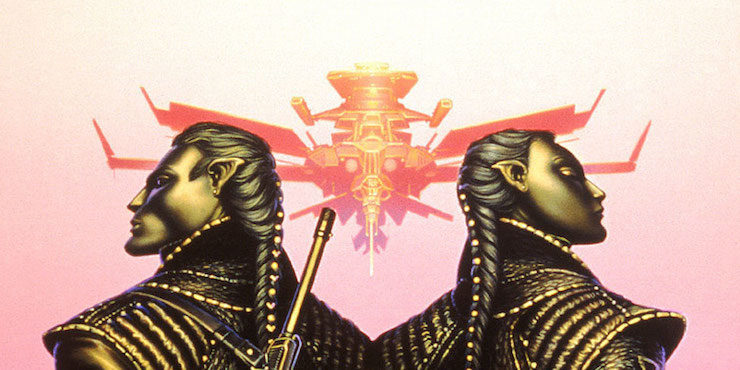

Top image: Foreigner cover art by Michael Whelan; DAW Books, 1994.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.