Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

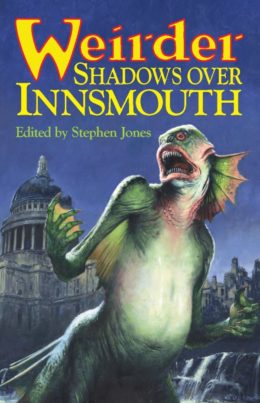

Today we’re looking at Brian Hodge’s “The Same Deep Waters As You,” first published in 2013 in Stephen Jones’s Weirder Shadows Over Innsmouth anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“At first it was soothing, a muted drone both airy and deep, a lonely noise that some movie’s sound designer might have used to suggest the desolation of outer space. But no, this wasn’t about space. It had to be the sea, this all led back to the sea. It was the sound of deep waters, the black depths where sunlight never reached.”

Summary

Kerry Larimer talks to animals. She finds the ability as natural as her other five senses. To others, it’s amazing enough to have landed her a show on the Discovery Channel: The Animal Whisperer. On the down side, her talent alienated her ex-husband, who even used it as evidence she’s too unstable to have custody of their daughter Tabitha. Kerry won that fight, but now Homeland Security’s “asking” her to consult on a project the agents can’t describe. It’s not until she’s on a helicopter, speeding toward an island prison off the coast of Washington State, that she learns what kind of “animal” the government wants her to “translate.” Colonel Daniel Escovedo tells her about a 1928 raid on Innsmouth, Massachusetts. The cover story was that the Feds were rounding up bootleggers. Actually, they were rounding up two hundred of these.

The photos show not people, but some travesty of mankind blended with the ichthyoid and amphibian. Once they were human in appearance, Escovedo explains. But either through a disease process or genetic abnormality, they changed, losing the ability to speak. Could be they be a hive-mind? At times they act like a single organism, aligning themselves toward the Polynesia from which Obed Marsh imported biological doom to Innsmouth. From that same area, underwater probes once picked up an anomalous roar, loud as an asteroid strike. And yet experts say the sound matches the profile of something – alive.

The government is concerned. It wants Kerry to coax some solid info from the Innsmouth detainees. She agrees to try, though the island is bleak and storm-plagued, no vacation destination. Worse, it’s surrounded by the kind of deep, dark water she’s always feared. Who knows what could be lurking under it?

Sixty-three detainees remain of the original two hundred. Dry cells never suited them; now they’re kept in a sort of sea lion enclosure into which ocean water periodically flows. Escovedo won’t let Kerry into the enclosure, though. Instead she meets the detainees one by one in an interrogation room. First hustled in is Obed Marsh’s grandson Barnabas, patriarch of the Innsmouthers. Kerry talks to him of the sea and its comforting depths. Or perhaps he somehow leads her to talk of it, for the sea is his only focus, to reclaim it his only yearning. From other detainees she picks up an urge to mate, something Escovedo says they’ve never done in captivity.

Kerry persuades Escovedo to let her meet Marsh in his own element. Chained to an all-terrain vehicle, Marsh at last re-enters the sea. Much as she dreads the dark water, Kerry dons wetsuit and snorkel and dives after him. Tell me what lies beyond, she thinks at Marsh. He answers with a whisper, an echo that builds into the image of a Cyclopean wall sunken to crushing depths.

Then Marsh lets out a bellow that hits Kerry like a pressure wave, like needles, like an electric shock. Thinking Kerry’s being attacked, Escovedo orders Marsh dragged back to land. Kerry surfaces in time to see soldiers shoot him to bits.

She tells Escovedo about the image Marsh sent her. In return he shows her eight photographs of ruins beneath the sea, taken by Navy submersibles that never made it back to their ships. A ninth photo he withholds. Escovedo says she has no need to know about that, since he’s sending her home the next day. He can’t risk exposing her to more detainees, not if Marsh’s bellow was what he thinks it was: a distress call.

That night Kerry’s racked by visions of swimming beside queer-angled phosphorescent walls. Barnabas Marsh remains with her, dead but still dreaming. She wakes to sirens, rushes outside. Everyone’s racing toward the prison, from which spotlights probe the stormy sea. The prow of a freighter appears. The ship runs up onto the island, rams the prison, collapses the outer wall. Massive tentacles tear down the remnants, and a subsonic rumble shakes the earth. Is it the Innsmouther’s god–or worse, only Its prophet? As the remaining sixty-two detainees escape into the waves, Kerry sinks to her knees, hoping only to avoid their vast rescuer’s notice.

Months later, she and Tabitha are renting a house in Innsmouth. Kerry climbs to the widow’s walk every day and gazes toward Devil Reef, wondering when they will make it home. Tabitha dislikes the half-deserted town with its unfriendly residents. Kerry distracts her with stories of sea-people who live forever. She thinks of how she gave her ex-husband all she had to give, and now they won’t let go of the rest.

One freezing February day, she witnesses the former detainees’ arrival on Devil Reef, where, salmon-like, they consummate their long-stifled urge to mate. Tabitha in tow, she hurries to the harbor, takes a rowboat, heads for the reef. The detainees hide in the waves, but Kerry can hear their song of jubilation, wrath and hunger. She tells Tabitha the end of their fairy story, how the sea-people welcomed a beautiful little earth-girl as their princess.

Some detainees clamber onto the reef, spiny and scaly and fearless. Others swim for the boat. They recognize Kerry. They jeer in her head. She’ll talk to them if she can, to tell them: I bring you this gift. Now could you please just set me free?

What’s Cyclopean: R’lyeh has “blocks the size of boxcars,” and “leviathan walls.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Kerry may be willing to talk with Deep Ones, but still describes them throughout as “abominations” and similar delightful descriptions. At the same time, she calls them “god’s creatures” and notes that their treatment is better than one might expect, given “how simple it was to dehumanize people even when they looked just like you.”

Mythos Making: Lots of echoes of Lovecraft here, not only the obvious Innsmouthian references but callbacks to specific lines. She and Marsh both come from the salt water, he’s just closer to returning. Then he’s “dead, but still dreaming.”

Libronomicon: No books, but some interesting reading in those files…

Madness Takes Its Toll: Kerry’s more certain of the Deep Ones’ return to Innsmouth “than any sane person had a right to be.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

The first time I read this story, the ending upset me so much I got a plot point out of it. On second read, I see more foreshadowing, and more interesting motivations for Kerry’s choice, than I picked up the first time. I probably read it very weirdly. There aren’t many authors who take the Deep Ones’ imprisonment seriously, and it’s something I appreciate but that also gets me thinking about every narrative choice very carefully. Call it a deep reading. (Sorry.)

We learn a few things about narrator Kerry up front. She’s terrified, Lovecraft-like, of the ocean. She loves her daughter. And she loves her work: “whispering” to animals of all species. She’s not psychic, she wants us to know. Though she doesn’t describe it this way, she’s a genius of empathy—and in spite of that, as prey to xenophobia as anyone else. The story is very, very ambivalent about which of these is the most appropriate reaction to the Deep Ones. Maybe both?

Kerry has worked to fight her phobia of the ocean. This wasn’t even a concept for Lovecraft—though maybe it was, after a fashion. He treated his own phobias like the most natural thing in the world, then wrote stories that played with the horror of people getting over them. In “Shadow Over Innsmouth,” in “Whisperer in Darkness” the real terror is that one might cease recoiling from the alien, the cosmopolitan, the unnatural. What, other than that oh-so-civilized terror, keeps us from giving in to the complementary attraction in attraction-revulsion? What else keeps us safely landbound, secure in our limited human bodies and limited, uncorrelated worldviews?

Kerry swings back and forth between attraction and revulsion, sometimes in the same sentence. She sees Deep Ones as just another of god’s creatures, then sees them as abomination and perversion. She imagines herself in their shoes, behind the same walls for decades, and still sees them as waking (and sometimes sleeping) nightmares.

Speaking of nightmares, many mythos stories hinge on how the author depicts Cthulhu’s relationship to his worshippers. Does he protect them? Ignore them? See them as dinner? How responsive is this deity, anyway? Hodge’s Cthulhu is a powerful protector—if you call when he’s awake. This is one of the best on-screen depictions of him I’ve seen. It beats the hell out of the original, primarily because of less ramming with ships. (Or at least, less ramming Cthulhu with ships—apparently the Sleeper in the Temple has a fine sense of irony.) Awe and danger both, depicted almost entirely through sound.

And then there’s that ending. A mom myself, my first instinct is revulsion, without the slightest edge of attraction. (Okay, except for when my eldest decides to roar like a T-rex while I have a headache. But she’s otherwise at very little risk of being traded to aquatic humanoids.) But moving beyond first instincts—which is what we were talking about, isn’t it?—the question of why Kerry trades her daughter becomes interesting. First there’s the obvious: more than the ocean, she fears losing the freedom to exercise her empathic talent. Her ex-husband saw her animal communers as rivals, and so they became. The Deep Ones are a much more direct threat: their “hive mind” seems to permanently take up her receptive power. Trade them something they want—children, and the infinite possibilities attending children—and maybe they’ll back off.

But they aren’t simply drowning out her extra sense. They’re pulling her into their world, maybe even making her one of them. To Lovecraft’s genetic fears, Hodge adds a “disease model” of amphibiousness, and hints that Kerry’s come down with a case of the Uncommon Cold. For someone who values her mental independence and hates the ocean… well, maybe Kerry’s daughter will appreciate the wonder and glory of Y’ha-nthlei a lot better than she will.

Anne’s Commentary

What makes a fictional character, a fictional race or species, a great creation? I think one criterion is how many people want to play with them, and how varied those responses are. “Secondary” treatments may closely resemble the “primary” author’s vision, enriching the original via detail and nuance rather than altering it. Other treatments may turn the original upside-down, inside-out and every which way but canon. And, as usual, an infinite sliding balance between faithful reproduction and radical revisionism.

By this criterion, the Deep Ones are a great creation indeed. Like the outrageous tsunami of organic aberration that pursues Lovecraft’s narrator out of Innsmouth, these toady and fishy and squamous and squishy humanoids have hopped and slithered and waddled all through the Mythos. In fact, one could argue that Lovecraft traversed the response-spectrum from aversion to sympathy in the single novella that started it all.

How should we feel when we feel about Deep Ones? Answer: Depends on which story we’re reading this week, whose authorial control we’re under, and how much we personally (viscerally) agree or disagree with that author’s take on our batrachian brethren. So far in this series, we’ve considered Howard’s ur-Deep Ones, at once our nightmares and (ultimately, for some) ourselves. We’ve shivered at what Derleth imprisoned in a shuttered room, at what Barlow glimpsed emerging from the night ocean, at the noir-tinged enormities of Newman’s “big fish.” With Priest’s “Bad Sushi” and Baker’s “Calamari Curls” we’ve gagged at the nauseous implications of tainted seafood. Wade’s “Deep Ones” appear in the guise of a young woman on the verge of sea-change as she bonds with a natural (porpoise) ally; the story teeters between terror and sympathy. Not without a fear-factor but dipping steeply toward sympathy is McGuire’s “Down, Deep Down, Below the Waves.” As for Gaiman’s froggy imbibers of Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar, who couldn’t laugh at and love them as cheery pub-crawling companions? At least, while you too are under the Peculiar’s influence.

Brian Hodge’s evocative “Same Deep Waters as You,” has become one of my favorite takes on the Deep Ones, a balancing act as difficult and successful as McGuire’s piece. In both stories, humans and Deep Ones are united in their ocean origins, may possibly converge again into one species down the long evolutionary line. Interesting that while McGuire shows her protagonist doing reprehensible things in the way of research without subject consent, death sometimes ensuing, the reader can comprehend her motives, can identify with her. Hodge’s detainees, Barnabas Marsh included, commit no such atrocities on stage. They’re the prisoners, the victims. They harm no humans, even during their escape — it’s their rescuer who does that and even then, far as we’re told, only as collateral damage to its demolition of the prison. And what do they actually do at story’s end? They mate, surely their natural right. They sing. They swim over to greet Kerry.

Curtain down. The reader has to imagine what comes next. But how many of us imagine something unspeakably horrible, featuring the bloody sacrifice of poor little Tabby? Most of us, I bet, because it’s what Kerry expects. Her connection to the Deep Ones was never warm and cozy like her connections to others among “God’s creatures.” In fact, it’s repeatedly described in terms of coolness, cold, the freezing pressure of the depths. Cold cold cold. The Deep Ones of “Waters” were once human, and yet they are profoundly alien now–inscrutable, remote, superior, as Kerry herself reads them. At last she realizes that her connection with Marsh (and through him the rest) was no triumph of her own talent but treachery, a trap. Marsh has exploited her. The detainees returned to Innsmouth sing with hunger and wrath, “their…voices the sound of a thousand waking nightmares,” because they too schemed against her. Like “fiends,” devils. And now they won’t loose their psychic grip on her until she gives them her most precious possession.

That is, if Tabby is Kerry’s most precious possession. Doesn’t Kerry mock the little girl’s whining to leave Innsmouth? Mightn’t her ex-husband have been right to contest custody, to suggest she was unfit because a bit cracked, your Honor? In readerly terms, is she a reliable narrator, an acute analyst of Deep One nature and intentions?

See the balance of the story dip back and forth? Mesmerizing, isn’t it? Are these Deep Ones oppressed innocents? Are they teh EBIL? Are they something in between? Tilt. Balance. Tilt. Maybe ending up more on teh EBIL side?

Maybe not?

That’s some nice writing there, a pinch of words in the balance pan of Deep One benevolence, another few grams of counterweight in the balance pan of Deep One alien malignity. Perhaps add the upsetting draft of a reader’s current mood.

Ambiguity’s fun, right?

Next week, Lin Carter’s “The Winfield Heritence” starts out by telling you not to read it. If you want to ignore the narrator’s well-meant advice, you can find the story in the Second Cthulhu Mythos Megapack.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” is now available from Macmillan’s Tor.com imprint. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.