“Fish are friends, not food!”

Before we get into this post, I must make a quick confession: of all of the Pixar films, this is probably the one I resent the most. Not because of anything actually in the film, I must say, but because of what has happened to aquaria since the film’s release: Hordes of little children squeaking “NEMO NEMO NEMO LOOK IT’S NEMO” even when the clownfish in question are OBVIOUSLY NOT NEMO SINCE THEIR FINS ARE PERFECTLY FINE SOMETHING YOU MIGHT HAVE NOTICED, KIDS, IF YOU WEREN’T SO BUSY SQUEAKING “NEMO!”

And that’s before we get into what this film did to one of the Epcot rides.

And with that out of my system, onto Finding Nemo.

Pixar’s animators started work on Finding Nemo with considerable confidence. They had produced three films that had been both critical and financial hits, and felt fairly confident that Monsters, Inc. would be their fourth such film. It was also the final film to arise from a 1996 pitch session, where Pixar executives had agreed that their next three films—all contracted to Disney—would be a bug film, a monster film, and a fish film, creating a little internal milestone. This order was later interrupted early in the development process for Toy Story 2, a film shifted from direct-to-video to wide release, but the concept of the fish film remained.

Director and co-writer Andrew Stanton felt particularly excited. He loved tropical fish. He also felt that he could bring two experiences from his own life into the film: visits to a dentist’s office that had a large tank of tropical fish, and a later trip to an aquarium with his young son—a visit where, Stanton later admitted, he’d been a touch bit overprotective, an element that was later used to drive most of Finding Nemo’s plot. And he loved clownfish. He started work on the script, with help from animator Bob Peterson and comedy writer David Reynolds, as others at Pixar were frantically rushing around to finish A Bug’s Life. Since the fish film wasn’t slated to start production for two more films, that meant that Finding Nemo had the luxury of starting with a completed script.

On the other hand, Finding Nemo had been left for last for good reason: the technical challenges facing the film vastly outweighed the earlier challenges of creating realistic fur, multiple bugs, and a full length computer animated film in the first place. For Finding Nemo, animators and engineers had to struggle through a problem that had stumped animators since the 1940 Pinocchio: animating underwater sequences. To this, John Lasseter added a new challenge: eager to show off Pixar’s growing technical skill, he ordered the world of Finding Nemo to look as natural as possible.

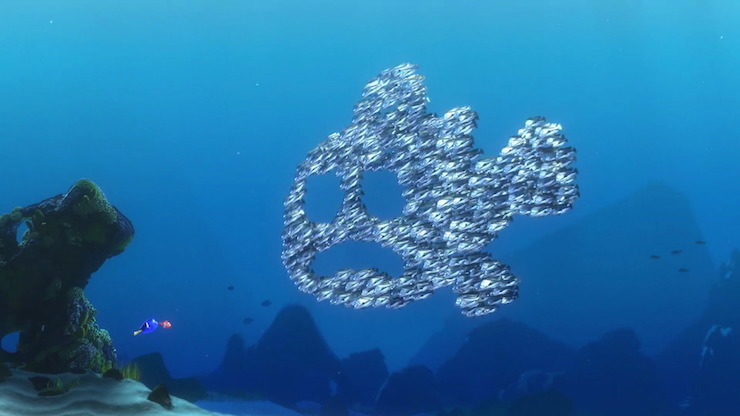

To get there, the animators and engineers watched not just Disney animated films, but also various underwater documentaries and Jaws. Pixar hired a fish expert from Berkeley, with the title of lead aquatic consultant, to teach the animators about fish. Not all of his instruction was used—Pixar decided, for instance, that Dory would wiggle her tail while swimming even if regal blue tangs do not actually do this in the wild—but animators used his lectures to create realistic looking fish movements, as well as adding some exotic critters to the reef scenes (for instance, the briefly seen, brightly colored sea slug). Some went scuba diving. Others studied a saltwater tank installed in Pixar’s production facilities for the occasion. A few of them even dissected fish.

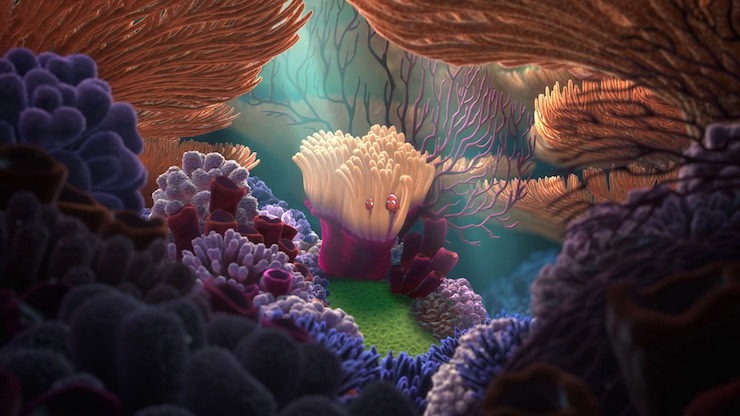

The worst part of animating underwater sequences wasn’t, however, getting the fish right, but adjusting correctly for the way the perception of light changes underwater. The second worst was adjusting for the movement of water, which can distort images—a particularly tricky situation for one of Finding Nemo’s biggest sequences: traveling with the help of sea turtles. The third worst was getting all of the myriad colors and details of coral reefs and their denizens correct. The animators, fortunately, had a new tool at their disposal: Fizt, the program developed to allow the monsters of Monsters, Inc. to have realistic looking fur, now used to make sure that little Nemo had realistic looking water.

The end result provided some amazing shots, including several which beautifully echo the look of sunlight on sands beneath shifting water. It also, in director Andrew Stanton’s opinion, was too realistic—several frames looked exactly like underwater photographs or video, instead of animated sequences. He sent animators and engineers back to their computers to create what Pixar would term hyper-reality—that is, something that looks realistic, but not quite photo realistic.

Stanton divided the animators and engineers into six separate groups to keep production running smoothly, a process that was only briefly interrupted by a visit from Hayao Miyasaki, there to work with John Lasseter on the English version of Spirited Away. The director took the opportunity to tour the Pixar offices (and the toy collections), as well as meet with Andrew Stanton and Brad Bird, to take a look at early bits from Finding Nemo and The Incredibles. Otherwise, everyone stayed bunkered down in the Pixar building to ensure that this film would be released in time, without the same sort of last minute rush that had hampered both Toy Story 2 and Monsters, Inc.

That turned out to be optimistic, but the end result, everyone agreed, was worth it.

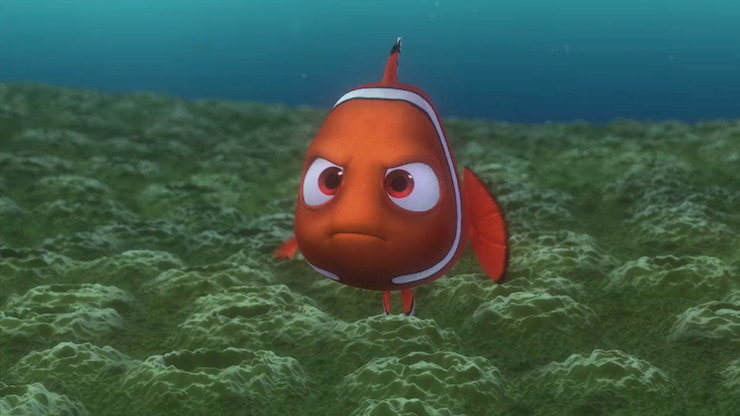

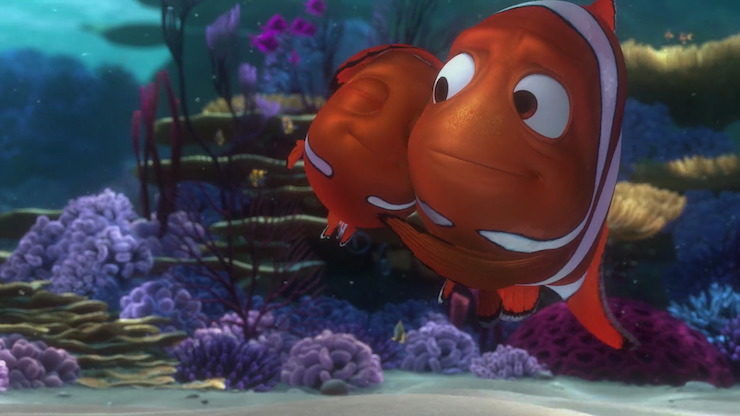

Finding Nemo opens by introducing us to habitual worrier Marlin, a small clownfish who has just moved to a brand new beautiful sea anemone right at the edge of a coral reef, overlooking the ocean. It’s an extraordinary view, and Marlin is proud of having secured the spot—if more than a bit worried about whether his wife Coral really likes their new home and whether the 400 or so kids he and Coral are expecting at any minute will like him. Before he can be completely reassured, he and Coral see a shadow off in the water. Coral, seeing those 400 eggs gleaming below, dives down –

Which is about when Pixar mercifully allows Finding Nemo to fade to black for a few seconds.

When colors return, Marlin discovers that he’s all alone except for one shaky little egg.

It’s easily one of the saddest moments in animation since Dumbo—possibly the saddest moment in animation ever. (Not that I sniffled on this most recent viewing, mind you, because I am now a grownup in full control of my emotions. It’s just that I don’t dust as much in this house as I really should. I expect you all understand.)

Fortunately, before anyone can become depressed for life, the film jumps forward in time to when that shaky little egg, now a fish named Nemo, is ready for his first day of school. Something—perhaps the trauma right before his birth, perhaps something else—has left him with a short fin. Marlin believes this makes little Nemo a weak swimmer. Nemo disagrees. The film mostly suggests otherwise.

And may I just pause here and note that I love how Finding Nemo handles this. As it turns out, this will be the first of at least three characters with a disability in one form or another: two fish with fin problems, plus one fish with severe mental issues. I say “at least” since I’ve heard a few viewers put the sharks and the very greedy seagulls into the disabled category as well. Two of these fish, Nemo and Dory, were born with their disabilities (the suggestion in Finding Nemo that Dory has always had these memory problems was confirmed in the sequel, Finding Dory). The third, Gill, acquired an injury that never quite healed. All three have to deal with others (primarily but not just Marlin) doubting their abilities. All three openly voice their frustrations. And Nemo gets to voice his frustration not just with his weak fin, but the way his father treats him because of that fin. To be fair, the fact that the rest of their family was brutally eaten has clearly left the already easily spooked Marlin deeply traumatized, but Nemo sees this as his father not letting him do anything and doubting his abilities.

At the end of the film, all three are still disabled, without a magical cure in sight. But all three have either accomplished their main goals, and/or found their places in the ocean (Gill is kinda stuck). And Marlin, after many misswims, has finally learned how to communicate with his son and give the kid the freedom the little fish needs. It’s both an idealized and a remarkably accurate picture not just of disability, but of many of the reactions to disability.

Finding Nemo also plays with and subverts various stereotypes about the various critters of the sea. A small blink or you’ll miss it moment involves a hermit crab and his shell. Jacques the cleaning shrimp cleans (and has to be deliberately told not to clean as part of the plot.) The sea turtles are completely chill, partly because they’re long lived, mostly because they’re turtles.

On the other side, Marlin frequently finds himself objecting to stereotypes about his species—”Actually, that’s a common misperception. Clown fish are no more funny than any other fish”—while simultaneously failing to realize that he’s operating under misperceptions of his own son. Three sharks desperately battle their own instincts and the perceptions about them, forming a nice contrast and analogue to Marlin’s assumptions about Nemo, while providing some of the most hilarious bits of the film—thanks in large part to Dory’s enthusiastic embrace of their creed.

Dory, incidentally, was a role both specifically written for and inspired by Ellen DeGeneres, whose monologues often feature her changing her mind multiple times in a single sentence, something Stanton adapted into Dory’s short term memory losses. For the other voice roles, Pixar cast a mix of established comedians, drama actors, Pixar animators (in brief roles), children of Pixar animators (in even briefer roles) and the director himself as the voice of chilled-out Crush the Turtle.

I suspect, though, that for the most part, what most viewers will remember is not the vocal work, excellent as it is, or the jokes, great as the shark sequence is, or even the action sequences, amazing as both the shark chase and the bouncing trip across glowing jellyfish are, but rather the rich relationship between Marlin and his only surviving son, and the spectacular beauty of this film, which to a degree not seen since Fantasia took the time to get everything right, right down to the patterns of shifting sunlight on ocean sands.

Even if this all led to the deeply unfortunate state of contemporary aquaria filled with small children shouting “NEMO NEMO NEMO!”

Finding Nemo was a box office smash, with its initial release bringing in $862 million at the box office, a total that in 2003 was beaten only by The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King. A later 3D release in 2012 added $72.1 million to that, for a box office total of $940,335,536 in 2013; Disney continues to release the film for special matinee performances each summer, adding to that total. The film was also a critical success, and took home several awards, including the Academy Award for Best Animated Picture.

On home video, Finding Nemo was even a bigger success, selling a jawdropping 40 million copies. Over a decade later, the film remains one of the most successful animated films of all time, and the DVD/Blu-Ray versions continue to rank in Amazon’s top 1000 sellers.

Even more impressive was the merchandising, which included toys and pillows based on all of the characters (I refuse to sleep with Nemo under my head, but I’ll admit the pillow is cute), mugs (the one featuring the seagulls squawking MINE MINE MINE does sorta sum up my attitude towards coffee in many mornings), clothing, cell phone cases, trading pins, and more.

Disney also added various attractions to many of their theme parks, including Turtle Talk with Crush (found at Epcot, Disney’s California Adventure, Hong Kong Disneyland and some of the Disney cruise ships); a roller coaster in Disneyland Paris; a musical at Animal Kingdom; and, in what I still consider a disastrous move, The Seas with Nemo & Friends, which was less a new ride and more Disney projecting images of Nemo, Dory and Martin ON THE GLASS COVERING THE GIANT AQUARIUM, preventing riders from SEEING THE ACTUAL FISH, SHARKS, TURTLES AND DOLPHINS swimming in the huge artificial coral reef that had been a staple of the park since 1986 like THANKS DISNEY. (My current advice is to avoid the ride entirely and just sneak in through the back of the building, allowing you to view the rest of the aquaria and exhibits, including Turtle Talk with Crush.)

Arguably, Finding Nemo had one other disastrous effect: demand for clownfish in tropical saltwater tanks expanded. Clownfish can be bred in tropical tanks, but are cheaper to obtain through fishing, leading several less than sustainable hunts for the cheerfully colorful fish, with methods including releasing cyanide into the water, to stun the fish to make them easy to collect. Other groups collected live coral from reefs to decorate tanks, placing additional stress on already stressed reef areas. Actual numbers are a bit dodgy, but multiple local groups in the Pacific and the Atlantic claimed that both coral reef and numbers of fish declined after “Nemo fishes,” accusing several outside fishing companies of corruption.

In addition, at least some upset small children and families then decided to “free” their little Nemos—either through plumbing systems or directly into oceans—either killing the poor fish in the first instance, or introducing an exotic species into nearby oceanic habitats in the second. The effects have not been conclusively measured (partly because oceanic habitats face enormous stress from numerous points, not just crying children) but may have somewhat contributed to coral reef declines.

On the other hand, ecological tourism groups in Vanatu noted that interest in their introductory scuba trips skyrocketed after the groups added a slightly inaccurate “Come see Nemo!” to their marketing and advertising. (The clownfish in the waters around Vanatu are a different species.) It seems possible that Finding Nemo inspired at least some small children, and perhaps even a few adults, to learn a little bit more about the oceans and coral reefs, and how to protect them for future clownfish.

Meanwhile, both Disney and Pixar had other concerns—most notably a declining business relationship punctuated by the threats of Steve Jobs to leave Disney and find another distributor. Not surprisingly, their next film would feature a man deeply unhappy with the constraints of his money-focused job.

The Incredibles, coming up next month.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Can’t disagree more on the The Seas with Nemo & Friends. I recently went to WDW with my 5-year-old daughter, and the three times we went to EPCOT, each time we did the ride AND Turtle Talk. She loved it, and also enjoyed walking through the aquarium proper afterwards. Aside from the Big Blue World earworm, part of the enjoyment of the ride is seeing the real fish behind the projected fish, and then, when you get off the ride, realizing that you can see them even better on two different levels. That and the EAC portion with the turtles, which is a pretty impressive effect even after you know how it works. I’d say the worst part is the line (even when it’s not busy, it’s a freaking maze).

By the third time I saw Turtle Talk, Crush actually acknowledged me when I was the only one who said “Dude!” Then I realized, I was becoming that guy.

However, I totally agree with the “NEMO NEMO NEMO” thing, which is why every time she saw a stinking clown fish, it was “a clown fish,” and every time she saw a stinking blue tang, it was “a blue tang.” And I have sufficiently avoided her doing that annoying thing that so many kids do. Whew.

Finding Nemo is one of my all-time favorites.

The scene of the ocean life gossip, with Marlin’s story getting more epic with each telling, is nothing short of, well, epic. It’s one of the many things in the movie that make me cry.

Plus, the movie taught en entire generation of viewers how to speaaaaak whaaaaaleeeeeee…. :P

I can’t tell you how much I love that Nemo’s parents are named Coral and Marlin. My great-grandparents were Cora and Martin, and Nemo always makes me remember the great times I had at their house when I was growing up.

This is one of my favorite Pixar movies, perhaps driven by the strong father/son dynamic. All the performers are spot on, the animation is great, and the pace is just right. The jokes surrounding Dory’s memory are not quite as funny now that my mom is in a memory care facility, but I still smile.

Count me as another who likes that Nemo ride leading into the Ocean pavilion at Epcot. I just love the Nemo musical that they stage at the Animal Kingdom, and that Big Blue World song is one of the reasons why, so hearing it again in the Nemo ride is a treat. And I enjoy the Turtle Talk exhibit. The Nemo additions to the pavilion help liven up what had been a kind of run down and stodgy exhibit.

And as I type this, in our nautically themed living room, my head rests on a “Mine Mine Mine” seagull pillow we bought the last time we were at Disney World.

I’m gonna agree with Mari on this one — my family was quite unimpressed with the Nemo ride at EPCOT, for exactly the reason you cited — the actual fish are obscured by the animated fish. On the day we went, the pavilion was almost entirely empty, and we didn’t stay long, so perhaps we missed some interesting parts, but between that and Journey Into Imagination (which was either closed for renovation when we went, or just generally being ignored), that whole part of the park seemed kind of dead and sad.

I’m not that invested in Marlin and Nemo, and I generally find fish creepy as hell (thank goodness they weren’t too realistic here), but Dory is fantastic, thanks to DeGeneres’s hilarious performance and the poignancy of her character. Although while Finding Dory was entertaining, I think maybe Dory works better as a supporting character than a POV character, since the latter requires cheating a bit on her memory retention. But that’s a discussion for a later post.

No, not EVERYTHING right, unfortunately. Yes, “Pixar hired a fish expert from Berkeley, with the title of lead aquatic consultant, to teach the animators about fish” but why they didn’t hire a bird expert? Despite the film taking place in Australia, the animators chose to animate American pelicans (Brown Pelican) and American gulls (Mew (Common) Gull or possibly California Gull, hard to tell) rather than the very different species found in Australia (Australian Pelican and Silver Gull). You can tell they are the wrong species because Australian Pelicans are completely white and not brown with a white head like Nigel and the gulls all have yellow legs and bills, unlike Silver Gulls which have orange legs and bills. Unfortunately, this biological inaccuracy happens in films a lot, it just bothers me that they got the fish right, but not the birds :(

This film has many marine-biology inaccuracies (besides the obvious ones), which I would be happy to enumerate, but I nonetheless consider it gorgeous and perfect and The Best EVAR and wouldn’t change a moment of it.*

I’ve been involved with marine-biology education since 2004, and Mari is absolutely right – clownfish elicit a steady stream of “IT’S NEMO!” I swear it’s been watched by every child in the USA since it debuted. Before that, most of them probably had no particular interest in those fish. But I love it anyway.

Its contribution to the reef-aquarium trade really, really stinks, especially since its apparent message was that “fish weren’t meant to live in a box” and taking them from their ocean home is wrong. And it does less forgivably give the message that “freeing” such fish is good. (Finding Dory is really bad about that, but we’ll get there). Still, those behaviors would have been hard to prevent. Boneheads will be boneheads. *sigh*

Dang would I like to be an “aquatic consultant” for a film like this. *pause* Or maybe not, if their disregard for my guidance drove me up the wall. Some inaccuracies have a purpose I respect, but deliberately making them look not-quite-realistic…why.

It’s wonderfully quotable. Its intricate beauty is the crown jewel of Pixar scenery, in my opinion. The characters are great. The messaging is mostly great – as a worrywart with physical disabilities and social difficulties, I relate to all of the central characters and feel strengthened when they are. Everything is awesome.

And it provides a handy way to prove my evilness by saying, truthfully, that I once watched Finding Nemo and then went out for sushi.

*Incidentally, I have those exact feelings about Diane Duane’s novel Deep Wizardry, and for similar reasons.

What is it about movies having a devastating effect on sea life? Jaws propagated a myth about the danger of man-eating sharks and provoked decades of unwarranted slaughter of sharks, with humans being a far greater threat to sharks than the reverse. And then Finding Nemo leads to havoc being wreaked on the clownfish population, albeit out of desire rather than dread. (Ooh. That name. I find clowns almost as creepy as I find fish.)

Can’t really disagree with any of this except maybe this:

I see this and raise you the opening sequence of Up.

Although Finding Nemo maybe the first CGI animated film to seriously tackle underwater sequences, the Transformers series Beast Wars, CGI animated by Mainframe, had several extensive underwater sequences in its third series in 1998. The animation doesn’t hold up well today, but by the standards of the time, its pretty remarkable.

@Aerona

Actually, being a consultant doesn’t help. I knew personally some of the guides employed to be set advisors and assistants on the climbing thriller The Vertical Limit which filmed in the mountains of NZ, and the resulting comedy was about as far from reality as you can get.

Literally every climbing sequence is wrong in some profound way. My friends and I were actually thrown out of a screening in Auckland for laughing too much at the inaccuracies. Although I did end up with some great gear bought dirt cheap afterwards, so I do have fond memories. The makers had bought tens of thousands of dollars worth of kit to stuff in rucksacks to throw off cliffs so it would seem more “realistic” before they were talked out of the idea. As if that ever was the problem…

*Also, what is wrong with going for sushi afterwards? It’s just vinegared rice in seaweed. Now sashimi on the other hand might elicit a reaction.

There’s always going to be inaccuracies. My father is a sheet metal contractor (translation: he makes ductwork for a living), and built some custom ducts for M. Night Shyamalan’s Split, for the characters to crawl through. While he was on-set, he did let someone know that the ducts weren’t realistic for the type of building they were supposed to be in, but that didn’t make a difference. Of course, the ductwork is unrealistic in just about any movie featuring ductwork, so he’s given that up for a lost cause.

Volcanologists get cranky when there’s unrealistic lava in a movie. Police, firefighters, and military folks spot inaccuracies in procedures and chain of command all the time. Let’s not even get started on computer networks and “hacking” as portrayed in films. If you add them all up, anybody who wants accuracy in a movie should stick to documentaries (and even there…). Fortunately, I edit technical books for a living, and that doesn’t come up in movies very often.

@10/Richard: I had the same thought regarding Up, and while I agree with you on an absolute scale, that scene mostly affects adult viewers. Kids don’t usually react. Of course, the same could be said of Nemo.

@11 and @12, absolutely true. Mine is that I know the expert on Roman games and spectacles who was Ridley Scott’s consultant on Gladiator.

I’ve also read the letter of retraction/apology she sent to pretty much every PhD classicist in the world when she was totally ignored.

@11: It was sashimi, actually. But saying “sushi” works on people who think sushi = raw fish.

@15 That reminds me of being quite disappointed that the Tokyo Aquarium had neither sushi nor sashimi in the cafeteria.

My family saw it at the drive-in when it came out & we all loved it. Gorgeous & fun & the voices were fabulous.

Sad about the clown fish boom & coral reef theft, honestly. On the plus side, it is now widely acknowledged that great white sharks all have Australian accents. ;-)

All parents have to let go; just hard to know when they know, you know?

My eldest son has Asperger’s and so we worked with him since 18 months to understand that while he is autistic, it does not define him. 18 years later, he is an Eagle Scout & in college. Still worry about him though; but I’m his dad so that’s a given. But he knows, you know (mostly, anyway) and that is good enough.

Kato

PS – Plus growing up north of Boston, Mass & having the lobsters saying “Wicked dahk down there” was fabulous – especially as we all still quote that line that at times. ;-)

PPS – @9ChristopherLBennet, I’ve never had a problem with fish – I had a tropical fish tank since I was little. Clowns, however, are evil. That’s it. My mum was recovering from a surgery in a local hospital & one of those visiting clowns was going to stop by & ‘cheer her up’ and she said ‘NO!’ very firmly – she was 70 at the time. :-)

@16: When interning at the New England Aquarium, I often lunched on clam chowder at the aquarium cafe. If the animals get to eat seafood, so do I. :-p

My mother and I went to see Finding Nemo some weeks after my grandmother’s death hoping it would cheer us up. It did. It’s totally adorable.

@17/Kato: I didn’t always have a problem with fish — we had goldfish when I was a kid — but as an adult, I just get squicked out by those flat, staring eyes and that scaly texture. I’m not sure why that aversion developed in me.

Although I’ve never cared for eating fish. In grade school lunches, the only reason I found the fish sandwiches palatable was because I could slather them in tartar sauce.

Probably my favorite “bit” in FINDING NEMO is when the aquarium denizens stage the “initiation into tankhood” for Nemo. Nemo’s been terrified, he’s in a state of total despair, but when they say, “We want you in our club, kid,” he immediately brightens up and says “Yeah?!” It’s such a wonderful moment of characterization; a realistic, instinctively “little kid” reaction.

@10 – I was thinking about Up too, but in Up you see that they had a long and fruitful (aside from their fertility issues) life together. The scene in Finding Nemo involves a young mother and their children all being slaughtered just as their life as a family is about to begin. So I’m going to have to say that’s a bit sadder, even if it doesn’t outright tug at you the way the Up prologue does.

@18 I was at an evening reception at the Boston Aquarium where they were serving sushi. All of a sudden, someone got a puzzled expression, looked over at the fish tanks, down at their plate, and said, “Just how fresh is this fish?”

@23: Teehee. I wonder if the staff of the adjacent Legal Sea Foods restaurant get asked that. Their fabulous cioppino certainly tastes fresh…

I read that Finding Nemo also inspired a trend for keeping Moorish idols like Gill, which do especially poorly in captivity. *SIGH*

I consider most of the inaccuracies in Finding Nemo to be minor, relatively insignificant to the plot, and/or justified by the Rule of Cool, reasonable plot needs, and/or the restrictions of a childrens’ film. Somehow this makes it feel fundamentally different from Finding Dory, whose plot hinges largely on a few huge, blatant inaccuracies.

Here’s a sampling, some of which are included in this article interviewing the aquatic consultant Adam Summers:

~Barracuda don’t eat fish eggs, though many other animals do.

~A real-life male clownfish would become female after losing his mate, and hook up with the first adult male to enter the vicinity…

~Those cute pink flapjack octopuses on the reef are a deep-sea species. Also their mouths should be down amid their arms. Pixar evidently couldn’t have characters talking out of their crotches, amusing though that would have been. (In Finding Dory, the squid has a properly-placed mouth; I forgot if the octopus does)

~Peach the sea star has a mouth in the right place but eyespots in the wrong place – two above the mouth, instead of one at the end of each arm.

~If Dory and Marlin descended to the abyss, the cold would probably kill them before the pressure squished them. And if they lived long enough to approach an anglerfish’s lure, she would swallow them both before they saw her face.

~They could not go into a whale’s mouth and out its blowhole because a whale’s digestive and respiratory tracts are not connected, which is why it can take in mouthfuls of water without asphyxiating. (This also happens in whichever of the gazillion film adaptations of Pinocchio featured an orca, which I watched as a young child and adored nonetheless because a sea monster ate people)

~A turtle hatchling might encounter its father (or any other relative), but neither of them would know they were kin.

~Fish don’t have eyelids. They also don’t have eyebrows, but the filmmakers adapted their hairless brow ridges to move in similarly expressive ways.

Hey, I’m an underemployed marine-biology educator, and take opportunities where I find them. And I adore this film.

I love the color of this film – I have to admit in some ways the film makes me nervous because the thought of witnessing your child’s kidnapping and then having to search the entire ocean plays into all my anxieties but it really is a great movie for all the reasons you outline, especially regarding the themes of family, independence, disability, etc.

We saw the musical at Animal Kingdom this past December and it was very good. My younger son was most enthralled by the bubbles that fly over the audience at the end though ;)

For whatever reason, although I like it, this hasn’t ever quite been one of my favorite Pixar films. It’s unutterably gorgeous, though.

(And just reading about it makes me want to dig out my copy of the BBC series Blue Planet, which I highly recommend.)

My two year old daughter loves both Finding Nemo and Finding Dory (she calls it “clownfish movie” – I managed to get her to remember that they were clownfish before she learned their names). We tend to watch Dory more, though, because my wife *hates* sad movies – and can’t force herself to watch the beginning of Nemo. (She was furious at me for conning her into watching Up early in our relationship, and still refuses to watch Inside Out).

I think my daughter prefers Dory, however, mostly because it has an octopus in it.

“Because it has an octopus in it” is a good reason for doing anything. :-)

As this article explains, in reference to the film, tropical sea creatures can and (unintentionally) do travel from the Great Barrier Reef to Sydney and beyond via the East Australian Current. But it doesn’t take them back north, and the film doesn’t show or tell of the gang’s journey home. Again, Finding Dory is vastly worse about this.

I am totally going to agree with Mari on The Seas ride complaint. I just got back from a wonderful trip to Disney World, the first time I’d been there in over 20 years. The day we did Epcot, I was excited to go on that ride, as I remember loving it as a kid, and I love ocean stuff in general. Boy, what a disappointment. You basically sit in giant moving clam shells watching video of Nemo playing hide-n-seek, which I can’t even imagine small children enjoying. Epcot is all about learning and exploring, and there was none of that happening on that ride. Even the aquarium at the end was a let down. There was one lonely dolphin swimming in one half of the tank, and a few fish swimming around in the other half of the tank. I predict that that ride will get a complete overhaul soon. It just seemed tired and dated.