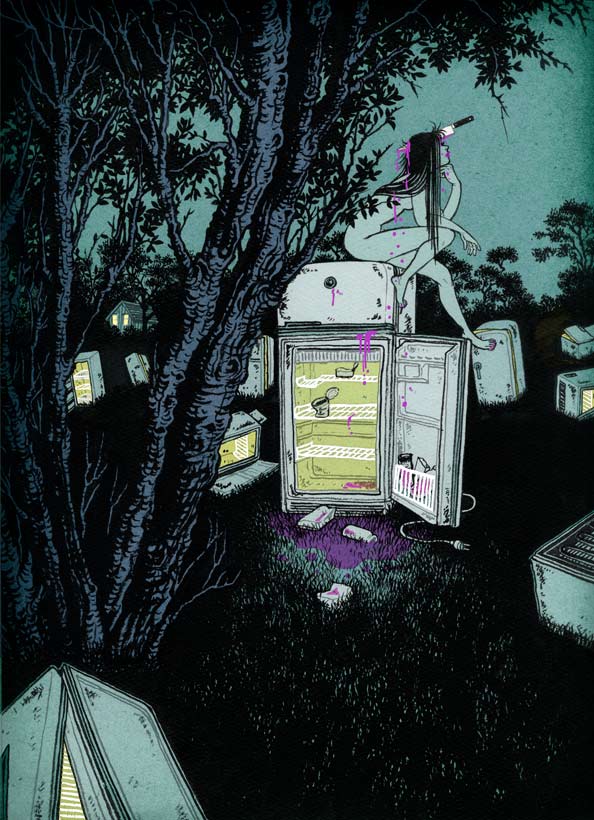

Undead girls begin re-entering the world of the living, emerging from refrigerators.

The staring. A leaf alone in the horrible

leaves. The dead girl. The staring.

—Joshua Beckman, “[The dead girl by the beautiful Bartlett]”

At 2:25 a.m. on a quiet Friday night on a deserted country road in southeastern Pennsylvania, the first dead girl climbed out of her refrigerator.

So the story goes.

We never saw the refrigerators. Eventually we gathered that they were everywhere, but we never actually saw them until the dead girls started climbing out of them. Holes in reality, some people said. Interdimensional portals, real Star Trek shit. There’s a tear between these parallel universes and something falls through, and next thing you know there’s a refrigerator in the middle of the road, or the sidewalk, or someone’s lawn, or a football field, or in the bottom of a dry swimming pool, or on the seventh floor balcony of a five star hotel. On the steps of a museum. Basically anywhere.

Later, watching a shaky video taken on someone’s phone, of a refrigerator on a long, straight line of train tracks. Train not far, nighttime, lights blinding. The blare of the thing sends the sound into an angry buzz of distortion. The fridge, just lying there on its side like a coffin. You can’t even tell what it is, except that it’s a box. Or something like that.

It opens. Kicked. Out climbs a broken doll girl, hair stringy and wet, head lolling to one side. Can’t see her face. Don’t need to see her face to know that she’s fucking terrifying. The train somehow looks terrified but physics is a thing, even now, and it can’t stop. She stands there, broken doll head on a broken doll neck, and over the heavy buzz you hear someone screaming holy fucking shit holy shit holy shi—

Even filmed on a shitty cell phone, a train derailed by a dead girl is quite a thing to see.

Okay: the official story goes that the first dead girl stood on that deserted country road on that quiet Friday night for quite some time. She stood motionless, listening to the pat-pat sound of her own blood dripping onto the blacktop. Not listening for her heartbeat, which was not there, nor for her breathing—which was not there either. She was listening to other things: wind, leaves, owls, fox scream, sighing of distant cars. It was a quiet night. That’s the story.

The story goes that the dead girl palmed blood out of her eyes and looked down at her sticky fingers, as if considering them carefully—in their context, in their implications. In the slick undeniability of what was still flowing out of her, like inside her was a blood reservoir which would take thousands of years to run dry. Like she was a thing made only to bleed.

And the story also goes that at some point, after studying the fact of her blood to her own satisfaction, the dead girl dropped her hands to her sides and started to walk.

We never would have believed, before the dead girls started climbing out of their refrigerators, that people could be literally resurrected by sheer indignation.

Probably it should have been obvious. People have been brought back to life by far more ludicrous means and for far more ridiculous reasons.

The story also goes that no one saw the first of the dead girls. The story goes that when they came they came quietly, unannounced, no particular fanfare. The dead girls did not—then—demand witnesses. They weren’t interested in that.

They wanted something else.

Later the dead girls were emerging everywhere, but the first dead girls climbed out of the dark, out of the shadows, out of the lost places and the hidden places and the places of abandonment—out of the places in which one discards old useless refrigerators. Out of the places in which one discards things which have served their purpose and are no longer needed.

The dead girls climbed into the light in junkyards, in vacant lots, in the jumble of shit behind ancient disreputable institutions one might kindly call antique stores. The dead girls climbed out in ravines and ditches and on lonely beaches and in dry riverbeds. Wet riverbeds. The dead girls climbed out into feet and fathoms of water. The dead girls climbed into the air but they also clawed their way out of long-deposited sediment and new mud, like zombies and vampires tearing their way out of graves. The dead girls swam, swam as far as they needed to, and broke the surface like broken doll mermaids.

This is how the story goes. But the story also goes that no one was present at the time, in the first days, so no one is entirely sure how the story got to be there at all. Or at least how it got to be something everyone accepts as truth, which they do.

First CNN interview with a dead girl. She’s young. Small. Blond. Before she was a dead girl she was definitely pretty and she’s still pretty, but in the way only dead girls are, which is the kind of pretty that repels instead of attracts, because pretty like that gives you the distinct impression that it hates you and everything you stand for. Dangerous pretty, and not in the kind of dangerous pretty that exists ultimately only to make itself less dangerous.

Dangerous pretty like a carrion goddess. You’ve seen that pretty picking over battlefields and pursuing traitors across continents. You’ve seen that pretty getting ready to fuck your shit up.

Small young blond pretty dead girl. Broken doll. She stands facing the camera with her head tilted slightly to one side. Her face is cut, though not badly. Neat little hole in her brow. The back of her head is a bloody crusted mess. It was fast, what made this dead girl a dead girl, but it wasn’t pretty.

But she is.

Looking at the camera—it’s somewhat cliché to say that someone is looking right into you, but that’s what this is like. The eyes of the dead girls aren’t cloudy with decay, or white and opaque, or black oil slicks. The eyes of the dead girls are clear and hard like diamond bolts, and they stab you. They stab you over and over, slowly, carefully, very precisely.

Can you tell us your name?

The dead girl stares. Anderson Cooper looks nervous.

Can you tell us anything about yourself? Where did you come from?

The dead girl stares.

Can you tell us anything about what’s going on here today?

Behind the dead girl and Anderson Cooper, a long line of dead girls is filing slowly out of the Mid-Manhattan Library, where approximately fifteen hundred refrigerators just came into material existence.

The dead girl stares.

Is there anything at all you’d like to tell us? Anything?

The dead girl stares. She actually doesn’t even seem to register that there’s a camera, that there’s Anderson Cooper, that she’s being asked questions. It’s not that she’s oblivious to everything, or even to anything; she’s not a zombie. Look into that diamond-point stare and you see the most terrifying kind of intelligence possible: the intelligence of someone who understands what happened, who understands what was done to them, who understands everything perfectly. Perfectly like the keen of the edge of a razor blade.

She’s aware. She just doesn’t register, because to her it isn’t noteworthy. She doesn’t care.

Can you tell us what you want?

The dead girl smiles.

What they didn’t seem to want, at least initially, was to hurt people. The train thing freaked everyone out when it hit but later as far as anyone was able to determine it hadn’t been done with any particular malicious intent. Mostly because the only other times anything like it happened were times when a dead girl needed to act fast in order to keep from being…well, dead again.

Dead girls wreaked havoc when they felt like someone or something was coming at them. So don’t come at a dead girl. Easy lesson learned quickly.

Dead girls have itchy trigger fingers. They hit back hard. You shouldn’t need to ask about the reasons for that.

Something like this, people struggle to find a name for it. The Appearing. The Coming. The Materializations. All proper nouns, all vaguely religious in nature, because how else was this going to go? By naming something we bring it under control, or we think we do—all those stories about summoning and binding magical creatures with their names. But something like this resists naming. Not because of how big it is but because of the sense that some profound and fundamental order is being altered. Something somewhere is being turned upside down. The most basic elements of the stories we told ourselves about everything? A lot of them no longer apply.

A bunch of dead girls got together and decided to break some rules with their own dead bodies.

So the mediums of all the media looked at this Thing, whatever the fuck it was, and they tried to attach names to it. Dead girls on the street, just standing, watching people. Dead girls in bars, in the center of the place, silent. Dead girls on the bus, on the train—they never pay the fare. Dead girls at baseball games—just standing there in front of the places selling overpriced hot dogs and bad beer, head slightly cocked, looking at things. None of them have tickets. Dead girls at the movies, at the opera, dead girls drifting through art galleries and libraries.

Very early on, a mass migration of dead girls to LA. Not all together; they went via a variety of transportation methods. Flew. Again, trains. Some went by bus. Some took cars—took them, because again: you don’t go up against a dead girl. Some—as near as anyone was able to tell—just walked.

Steady. Inexorable. The news covered it, because the dead girls were still always news in those days, and while even news made up of a wildly diverse collection of media and organizations usually adopts a specific tone for something and sticks to it, the tone for this coverage was profoundly confused.

Watching dead girls standing in the aisle of a jumbo jet. Refusing to be seated. Staring. Interrupting the progress of wheely carts and access to the tail-end restrooms. This specific dead girl is missing half her face. Blood oozes from the gaping horror. Flight attendants don’t look directly at her, and one of them gets on the PA and apologizes in a slightly shaking voice. There will be no beverage service on this flight.

Cut to the ground below. Twenty-four dead girls have run into a biker gang and confiscated their vehicles. They roar down a red desert road in loose formation, hair of all colors and lengths pulled by the hands of the wind. They’re beautiful, all these dead girls. They’re gorgeous. They take whatever name anyone tries to give this and they hurl it off the tracks like that train.

You get the sense they’re pretty sick of this shit.

That’s the thing, actually. There are exceptions: girls with horrific traumatic injuries, girls missing limbs, girls who were clearly burned alive. A lot of those last. But for the most part the flesh of the dead girls tends to be undamaged except for the small evidences of what did them in, and there’s always something about those things which is oddly delicate. Tasteful. Aesthetically pleasing.

As a rule, dead girls tend to leave pretty corpses.

Dead girls outside movie studios, the headquarters of TV networks. The houses of well-known writers. Assembled in bloody masses. Broken dolls with their heads cocked to one side. Staring. People were unable to leave their homes. This is how it was. Footage constant even though nothing changed. People started throwing words around like zombie apocalypse but no one got chomped on. The dead girls didn’t want the flesh of the living.

Initially police tried to clear them out, then the National Guard. Casualties were heavy. One of them—a girl with long, lovely brown hair gone reddish with blood—threw a tank. So people basically stopped after that. What was this going to turn into? One of those old horror films about giant radioactive ants? More contemporary ones about giant robots and sea monsters? Maybe we weren’t ready to go quite that far. Maybe you look into the eyes of a dead girl and it feels like your options dry up, and all you can do is be looked at.

You were part of this. We all were. Complicit. Look at yourself with their eyes and you can’t help but see that.

Except on a long enough timeframe everything has a half-life. Even the dead.

You don’t get used to something like this. It isn’t a matter of getting used to. You incorporate.

Dead girls everywhere. Dead girls on the street, dead girls on public transportation—staring at phones and tablets, reading over shoulders. Dead girls in Starbucks. Dead girls on sitcoms—no one has ever really made a concerted effort to keep them out of movie and TV studios, after a few incidents where people tried and the casualty count wasn’t negligible. Dead girls on Law & Order, and not in the way that phrase usually applies—and man there are a whole fuck of a lot of dead girls on Law & Order. Dead girls in the latest Avengers movie. Rumor has it dead girls surrounded Joss Whedon’s house three months ago and haven’t left, and have decisively resisted all attempts to have them removed. Dead girls vintage-filtered on Instagram.

Dead girls on Tumblr. Dead girls everywhere on Tumblr. Dead girl fandom. There’s a fiercely celebratory aspect to it. Dead girl gifsets with Taylor Swift lyrics. Dead girl fic. Vicarious revenge fantasies that don’t even have to be confined to the realm of fantasy anymore, because, again: Joss Whedon. And he’s by no means the only one.

Dead girls as patron saints, as battle standards. Not everyone is afraid of the dead girls. Not everyone meets that hard dead gaze and looks away.

Some people meet that gaze and see something they’ve been waiting for their entire lives.

So in all of this there’s a question, and it’s what happens next.

Because incorporation. Because almost everyone is uncomfortable, but discomfort fades with familiarity, and after a while even fandom tends to lose interest and wander away. Because we forget things. Because the dead girls are still and silent, constant witnesses, and that was unsettling but actually they might turn out to be easier to ignore than we thought. Or that prospect is there. In whispers people consider the idea: could all the pretty dead girls climb back into their refrigerators and go away?

Is that something that could happen?

It seems vanishingly unlikely. Everyone is still more than a little freaked out. But it is an idea, and it’s starting to float around.

We can get used to a lot. It’s happened before.

A deserted country road in southeastern Pennsylvania—deserted except for a dead girl. Quiet night. Silent night except for her blood pat-patting softly onto the pavement. Palming it out of her eyes, staring at her slick, sticky fingers. Dropping her hand limp to her side.

A dead girl stands motionless, looking at nothing. There’s nothing to consider. Nothing to do. The entire world is a stacked deck, and the only card she can play is that she’s dead.

That might or might not be enough.

The dead girl starts to walk.

“eyes I dare not meet in dreams” copyright © 2017 by Sunny Moraine

Art copyright © 2017 by Yuko Shimizu