Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

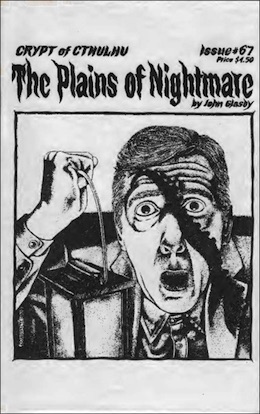

Today we’re looking at John Glasby’s “Drawn From Life,” first published in the Michaelmas 1989 issue of Crypt of Cthulhu. Spoilers ahead.

“And the music! It rose and fell in wild, tormented shrieks and cadences as if the instrument had a soul of its own which was in mortal danger of being lost forever in the fires of Hell.”

Summary

Certain unmentionable things occur on “the very rim of human consciousness,” but our unnamed narrator is driven to mention them, lest ignorant public authorities pull down a certain house at the end of Mewson Street and discover apocalyptic horror! For Mewson Street is not only on the outskirts of London but on the outskirts of reality as we know—and cherish—it.

Narrator’s busy writing a book on lesser-known contemporary painters, and frequents bookshops and studios in search of material. One day he stumbles on a dingy shop in an obscure Chelsea square. Its offerings are of little interest, except for a canvas signed “Antonio Valliecchi.” The landscape depicts a rocky plateau drifted with green sand and faced by a cave-riddled cliff. In the cave mouths, the artist has painted the vague yet deeply disturbing outlines of eldritch things. No horror magazine daub this, but narrator buys the bizarre masterpiece for ridiculously little. Could this Valliecchi be the same man as the renowned violinist? The shopkeeper doesn’t know.

Narrator spends months looking for more of Valliecchi’s work. Finally, during an after-dark wander through tangled streets, he spots a shop window featuring two works in Valliecchi’s super-realistic style. One shows robed celebrants in a vast cavern. They look like they might not be quite human. There’s no doubt about their monstrous idol, which is “hideous beyond all belief.” The other painting, titled “Void Before Creation,” shows suns and planets, beasts and men, arrayed around a vague black tentacled mass. The image seems to suggest that all things were “originally formed out of utter evil and chaos and would remain tainted with it until the end of time.” The shopkeeper says he bought the paintings from Valliecchi himself. The painter is indeed the violinist, and in the shopkeeper’s opinion a haunted and frightened man.

A week later, narrator learns that Valliecchi will be performing at his exclusive club! What a coincidence! He goes to the concert and is surprised to find the artist an ordinary-looking little man in his early sixties. His eyes do look haunted, though, and his music rises and falls in “wild, tormented shrieks and cadences as if the instrument had a soul of its own which was in mortal danger of being lost forever in the fires of Hell.” What’s more, narrator has “the uncomfortable feeling there were curious antiphonal echoes coming from somewhere out of the distance in answer to that strange music.”

After the performance, narrator tells Valliecchi he owns three of his paintings and wants to discuss his artwork. Valliecchi at first denies he ever paints, but he also gives the impression he desperately wants to get something off his chest. At last he gives narrator his address in Mewson Street.

Narrator seeks him out that very night. Mewson Street turns out to be narrow, cobbled, decayed. A “humped” bridge leads to a hill from which narrator can see the lights of London, and there he finds Valliecchi’s isolated home.

The interior’s ordinary enough until Valliecchi shows narrator into his studio. On its walls are pictures far more horrible than the three narrator owns. Valliecchi watches narrator closely, as if gauging his reactions. No one else has seen the pictures, he confesses, but perhaps narrator can understand. Was not narrator affected by his playing that night? Would he be surprised to learn the music was written ages before any great composer he could name?

Just as narrator begins to fear he’s dealing with a madman, Valliecchi drags him toward a heavily draped window. Let narrator see what Valliecchi has seen for so many years, see what his music can call forth!

Behind the curtains is no depraved mural, only a window into the dark night outside. But when Valliecchi begins to play his Stradivarius, the window becomes a portal to the hideous places he’s painted: the green-sanded plain with caves that spew worm-like demons, a burial ground desecrated by ghouls, all the visions of Earth’s early priests, all the terrible truth that spawned man’s myths. These are the gods that walked before even Mu and Lemuria rose from the waves!

Narrator screams, but is paralyzed beyond escape—also the door’s locked. As Valliecchi’s music reaches new heights of hysteria, the window goes black. Black with the blackness of ultimate chaos, and what lurks there: an amorphous and ever-changing intelligence, purely evil. Valliecchi tries to change his tune but it’s too late. Inky tendrils ooze through the window and draw the man screeching into outer darkness.

Narrator flees mindlessly, somehow making it home. Now, he seldom ventures out at night. He can’t explain what happened on Mewson Street, but he does know what he saw in his last backward glance.

What lay behind the drapes in Valliecchi’s studio was no window at all, only a blank brick wall.

What’s Cyclopean: The cave openings in Valliecchi’s cliff are full of “eldritch things.”

The Degenerate Dutch: The ancient Egyptians apparently worshipped pre-Lemurian gods called up by off-key fiddle music. (Pre-Mu, too. There’s no poetic word for things that happened before the rise of Mu, which is probably why Lemuria and Atlantis are so much more popular.)

Mythos Making: Clark Ashton Smith’s paintings are “horrifying enough,” if one understands their hidden meaning…

Libronomicon: …let’s not even talk about the naïve folks who read horror magazines, though.

Madness Takes Its Toll: When he meets Valliecchi, narrator’s convinced that he’s in the presence of a madman. But after that, he mostly questions his own sanity. He ends the story phobic of shadows, which isn’t necessarily unreasonable under the circumstances.

Anne’s Commentary

John Glasby (1928-2011) was a research chemist and mathematician, the author of Encyclopedia of the Alkaloids and Boundaries of the Universe. But when he felt like getting serious, he’d don any of a multitude of pseudonyms [RE: including “Ray Cosmic”] and bat out fiction: crime and mystery, science fiction and fantasy and horror, war stories, spy stories, westerns, even hospital romance. Yes, hospital romance is, or was, a thing. Nothing could be more erotic than the glint of freshly autoclaved scalpels, the tender squeak of gurney wheels, and the sweet scent of disinfectant, am I right?

I’m thinking of a series of very graphic novels: Herbert West, Reanimator, meets Cherry Ames, Student Nurse. Call my agent, publishers. We’ll set up an auction.

But about “Drawn from Life.” Sometimes less is more, especially at short story length. This one is groaning a little too loudly with Lovecraftian tropes. To name a few:

- Mankind is not meant to know too much. On the other hand, somebody has to know too much, in order to warn the rest of us against knowing too much.

- Venturing into odd little shops is dangerous. Ditto wandering in maze-like neighborhoods you’ve never seen before. Cobblestone streets and decrepit houses are a dead giveaway.

- Artists of the bizarre are either crazy or know too much or are crazy because they know too much. Or know too much because they were crazy to begin with. They usually paint either trans-Saturnian landscapes or ghouls or both.

- If a musician plays tunes you can’t hum along to because wildly atonal, beware. Violins and pipes seem especially suited to such tunes.

- If a window is heavily draped, leave the drapes be.

- Oh that I ever saw it!

- People will call me mad or overly imaginative or obsessed, but I know what I saw!

- Don’t bore the reader by describing your escape following the Big Scare. Just flee blindly/mindlessly and end up at home.

- Wormy things are scary. Also tentacled things. Also animal-tainted humanoids with red eyes. And especially black amorphous things, with vast inhuman intelligence. And tentacles.

- First person narrators should go nameless, while they live bachelor lives without familial obligations and write monographs about subjects at least tangentially related to their eventual obsessions. They should also be prone to coincidences that further the plot. Unless those coincidences are actually malign fate?

Sometimes more is more, as in: If one “mad” genius is good, why not two, or two-in-one. Here we’re talking Richard Pickman, the hyperrealistic painter, and Erich Zann, the violinist whose outre strains link him to other dimensions and summon problematic fans. I didn’t buy the mash-up here, alas, probably because I didn’t buy Valliecchi being a sublime genius in two very different arts, the visual and the aural. The story was too short to support the notion, gave too little detail.

Too little detail, too little specific and piquant detail, too little concentrated atmosphere. “Drawn from Life” is another story that, of late, has heightened my appreciation of Lovecraft’s, um, craft. Compare it to “Pickman’s Model” for detail, and detail beyond the cliche, the expected, like the painting of ghouls laughing over a Boston guidebook to supposedly still-interred notables. Compare Mewson Street to the Rue d’Auseil for eerie vividness.

I was thinking the Big Scare of the story was Azathoth, because Chaos associated with ear-lancing music. But it’s intelligent, an attribute one associates with Nyarlathotep. Of course, it could be both, Azathoth manifesting as Soul and Messenger. Or it could be a generic cosmic horror. To be fair, our nameless narrator wouldn’t know.

I was thinking, too, whether narrator needed to worry about the last house on Mewson Street being razed. If Valliecchi has been opening portals to beyond for many years, then the portals aren’t associated with any one place, but rather with Valliecchi and his music. I guess he created portals wherever he played the right tunes. What narrator really needs to worry about is whether he’s inherited Valliecchi’s connection to beyond. Like, what if he stops writing harmless art criticism and starts writing really, really scary stories that open “windows” in “brick walls?”

I was thinking, finally, about whether the Intelligence snatched Valliecchi’s Strad away with Valliecchi. Because that would have been really rude, as far as us music lovers are concerned. Though, yeah, could be one of the Servitors at the heart of creation is sick of its everlasting whiny pipe and wants to whine on the violin for a change.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

One of my own childhood phobias was born of a short claymation film, played for my class by a music teacher who was feeling either uninspired or sadistic. In the film, a band sets up on a forested slope to practice, I think, Joplin’s “The Entertainer.” The mountain erupts, the band is destroyed along with the surrounding ecology, and I ended up terrified of 1) seismic activity, and 2) “The Entertainer.” I kinda sympathize with our narrator’s newfound fear of shadows, is what I’m saying.

Be careful where you practice your instruments. You never know when powerful, inimical natural forces might be feeling judgy.

In addition to providing a timely warning about what happens when your music fails to soothe the savage beasts, this week’s story appears to be fanfic for Erich Zann. It has overtones of Richard Upton Pickman as well, but the clear spark seems to be the desire to know what terrors lay outside Zann’s window. Who doesn’t, reading that story, yearn for just a little more detail about the inhuman movement filling the void beyond the Rue D’Auseil? There are advantages, of course, to showing the reader less than she wants to see—but sometimes you just want all the gory abominations.

And we do glimpse some fabulous abominations. A good three quarters of Glasby’s prose in this story is an iffy effort to sound Lovecraftish—the hideous affair and the terrible happenings and the shocking events and the horrendous truth. (And that’s just the first paragraph.) But the other quarter breaks through into at least hints of genuine hideousness. The window where no window should be, blank as an inactive screen. The wormlike beings of uncertain size, creeping out of their caves to listen to Valliecchi’s ancient song. (Poor worms, they still get a bad rap.) The dark thing, almost invisible, in the void before creation.

And that same dark thing, here and now, slipping a tentacle through the wall of illusory safety between its world and ours to snatch Valliecchi. And leaving behind the question of why. Is it, as I suggested facetiously above, merely a cosmic music critic? Or the converse—does it want the violinist for its cosmic orchestra, perhaps playing alongside Azathoth’s tuneless flutes? Was V just unlucky enough to hit on the melody that cries: “Here I am, the chosen sacrifice, come eat me?” And that uncertainty leads to a greater and more terrible uncertainty: what is it, exactly, that drew the Power’s attention? Could it happen to you, if you happened to look in the wrong direction or hum in the wrong key?

About that Power: actually Azathoth? I always think of Azathoth as blindingly bright, rather than void-within-the-void darkness. But I may be pulling that from my persistent misinterpretation of “Whisperer in Darkness’s” description of a “nuclear horror.” Intellectually, I know that for Lovecraft, “nuclear” just meant “central.” Nevertheless, the unintended image has infiltrated my whole concept of the mindless god with weird taste in wind instruments. Mushroom clouds and piccolos, that’s where my head goes every time.

On a more serious note, one thing I appreciate about “Drawn From Life”—despite the spoilerific title, tropey overload, and “mere words cannot describe this… any way other than the way that I just did” language—is the portrayal of art connecting with art. Valliecchi is a genius musician, but in order to fully understand his music he turns to painting. The synaesthetic connection between different forms of creativity, between sound and sight, hints at the more mundane ways that artists struggle to understand their own experiences—and to communicate them. Anne’s right that “Drawn From Life’s” short length doesn’t do this theme justice. For me, though, it feels worth playing out at greater length, minus the tentacular cut-off.

Speaking of a sudden, legit fear of shadows, next week we dip back to M. R. James’s “Casting the Runes,” with bonus rude responses to rejection letters.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” is now available from Macmillan’s Tor.com imprint. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.