Sometimes, you’re just trying to fish a little to get by and bring home some food to your hovel. And sometimes, you pull up a magic fish, and find your life transformed—for a little while, anyway.

The Grimm brothers published The Fisherman and His Wife in 1812, in their first volume of their first edition of Household Tales. They noted that the tale was particularly popular in Hesse, told with several variations, sometimes with doggerel rhymes, and sometimes in prose, without any rhymes—versions, they sniffed, that were rather lesser as a result. Their version, therefore, included the rhymes, which has led to numerous differences in translations. Some translators decided to leave out the rhymes entirely; some decided to go for a straightforward, non-rhyming English translation, and some decided to try for English rhymes. This leads to something like this:

The original German:

Mandje, Mandje, Timpe Te!

Buttje, Buttje, in der See,

Meine Fru de Ilsebill

will nich so as if wol will.

As translated by Margaret Hunt in 1884:

Flounder, flounder, in the sea,

come, I pray thee, here to me,

for my wife, good Ilsabil,

wills not as I would have her will

…by D. L. Ashlimann in 2000:

Mandje, Mandje, Timpe Te!

Flounder, flounder, in the sea!

My wife, my wife Ilsebill,

Wants not, wants not, what I will

…and by Jack Zipes in 2014:

Flounder, flounder, in the sea,

If you’re a man, than speak to me

Though I do not care for my wife’s request,

I’ve come to ask it nonetheless.

The last translation, if considerably freer than the others, does do a rather better job of summing up the fisherman’s thought process for the rest of the story, but overall, the impression left by this is that short stories containing doggerel poetry like this will not always translate well into English. So with that caveat, onwards.

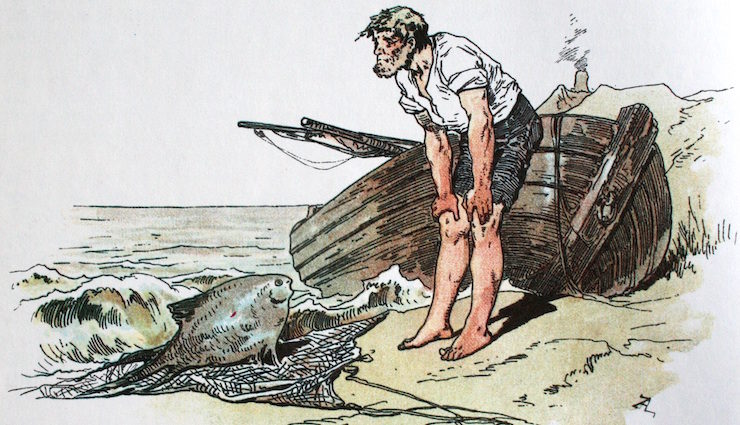

The fisherman and his wife are in decidedly bad shape at the start of the story, living in a barely habitable hovel, with apparently nothing to eat but fish. On top of this, the fisherman is not really having a successful day of it. As we eventually learn, he’s caught pretty much nothing for the day. And then, finally, his hook catches on something—a talking fish.

Well, something that at least looks like a talking fish. The flounder claims to be an enchanted prince, and given that it can and does talk, I’m willing to accept this—although as it turns out, I think that just possibly “enchanted prince” is a bit of an understatement. The sort of things this fish can do are the sorts of things usually associated with demons or powerful fairies, not enchanted royalty. Maybe the fish meant to say that he was a prince of enchantment—that is, a fairy spending some time as a fish. Not that the fish really dwells on this: he’s more interested in persuading the fisherman that really, he—that is, the fish—will not taste very good. The fisherman has to agree. And, he realizes, he really can’t kill a talking fish. He releases the bleeding fish back into the water and returns to his hovel, empty handed.

As it turns out, this is a major mistake—his wife, presumably hungry, wants to know why he didn’t bring back any fish, asking him if he caught nothing. The fisherman then makes his second mistake: he tells his wife the truth. She immediately jumps to a conclusion he missed: a fish that can talk is the sort of fish that can grant wishes. She’s apparently read her fairy tales—at least some of them.

The wife figures that they can at least ask the magic fish for a cottage, which seems reasonable enough. I would have added some chocolate, at least—if you’re going to ask for a magic cottage, you should always ask for it to be furnished, and I think we can all agree that chocolate is an essential part of any home furnishings. The fisherman heads out, and sure enough, the wife is correct—the magical talking fish can, indeed, grant them a cottage—a rather lovely little one, complete with hens and ducks.

It’s not enough.

I blame the poultry for what happens next—I assume their squawking kept the wife up, which helped give her insomnia, which made her cranky, which made her unhappy with everything, including the cottage. I may be projecting. (My next door neighbor has a rooster.) Anyway, regardless of why, a few weeks later, the wife wants a castle. Her husband objects, but heads out to the fish anyway. The castle, too, is not enough (even though it comes with ready-made fine food, presumably the fish trying to ensure that hunger pains won’t lead the woman to bother him again): she wants to be king. Even king is not enough: she wants to be emperor. Even emperor is not enough: she wants to be pope. Which leads to a gloriously incongruous scene where the fisherman—presumably in somewhat better clothing these days—manages to walk from the sea where he caught the flounder all the way to St. Peter’s in Rome, just to say, “Wife, are you pope?” Even that isn’t enough. I suppose some people just can’t appreciate the historical significance of becoming the first official (or fairy tale) female pope, legends of Pope Joan aside.

The tale is mostly, of course, a warning against ambition and reaching too high. But reading this version of the tale, what strikes me is how the tale also notes just how easily the status quo—that is, king, emperor, pope—can be changed, while also arguing that doing so will not increase anyone’s happiness. In this, the story seems to be shaped not by folk or fairy tale, but by contemporary events.

By the time the Grimms published this tale in their first edition of Household Tales, one empire, once thought nearly immortal, had already fallen. A second was to fall by the time they published their third edition, destroyed by yet a third empire whose own fate, for a time, had seemed uncertain. The Pope—presented in the story as a figure of awesome power, above all other political figures, even an emperor—had been virtually helpless and incompetent against the march of Napoleon’s forces through Italy in 1792-1802, a march that, although no one could foresee it at the time, created political chaos that eventually led to the end of the Papal States.

In other words, the story was told in a time when it was plausible for someone from comparatively humble beginnings to rise to the position of Emperor—and lose it, as well as a time when the Papacy, while still the unquestioned head of the Catholic Church, also seemed to be under threat. And not just emperors and popes, either: Napoleon’s march through Europe left social havoc and change everywhere. Sure, Napoleon accomplished all this through his own efforts, not through a magical fish, but the results were similar (and to be fair, a few of Napoleon’s contemporaries were convinced that he was receiving magical or mystical aid.) The tale is forceful in its message: change can happen, but don’t reach too far—and be grateful for what you have. Otherwise, like Napoleon, you might find yourself tumbling down again.

Though it’s significant, I think, that in the tale, the ambitious person does not rise and fall alone. In the end, he joins her in their old hovel. It’s not entirely unfair—he, after all, is the one making the actual request to the fish, and he, after all, is the one facing the increasingly worsening weather each and every time he asks the fish for something more—weather that should have warned him that he was on dangerous ground. And yet, when faced with increasingly outrageous demands from his wife, he does nothing but make a few hollow protests, asking her to be content. In this sense, this is also a tale noting that words may not be enough: those going along with the ambitious may be brought right down with them—even if they tried to advise a wiser course of action.

In that sense, this is yet another tale published by the Grimms that argues not just for the return of the old social order, but for social stability, arguing against changing the status quo—fitting right next to stories like “The Goose Girl” and many more.

And yes, there’s more than a touch of misogyny here as well. The tale, as the Grimms noted, draws upon a long history in myth and literature of the nagging wife who forces her husband to try to move beyond his station. In the Grimm version, the husband is portrayed as a mostly passive figure, despite his protests to his wife—but only mostly passive. Knowing that the requests are wrong, and knowing he is making these requests anyway, he blames his wife, not himself for going along with her. Particularly in the end, when she wishes to be God.

The version recorded by the Grimms was shaped by something else as well: poetry. And not just the repeated doggerels of the tale, either, but poetic descriptions of increasingly worsening weather, matching the increasingly serious requests by the wife. These descriptions may have been in an original oral version, or may have been—just may—added by the person who told this version to the Grimms: Ludwig Achim von Arnim, nobleman and poet.

Von Arnim, who had also trained as a doctor, found himself fascinated by folklore and legends, and worked with Goethe on a collection of folksongs. He also befriended the Grimm family, encouraging their folklore studies and passing on folktales that he claimed to have heard—without noting if he had, shall we say, improved on them. His daughter Gisela von Arnim, also a writer, eventually married Wilhelm Grimm’s son Herman Grimm.

As I hinted earlier, the Grimms noted other variants. Some of these variants had slightly different doggerel poems; others lacked any poetry at all. In some versions, the cycle ends when the fisherman says he only wants his wife to be happy. When he returns home, they are back in their hovel—but his wife is happy, and remains so to the end of her days. This is the version I liked best when I was a kid, a version that, while not granting its protagonist everything, at least gave them a small reward for ambition, instead of choosing to crush their hubris, and leave them trapped in poverty, with no hope of escape. A version that might lack the power and ethics of the original version, but that feels like just a touch more of a fairy tale.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.