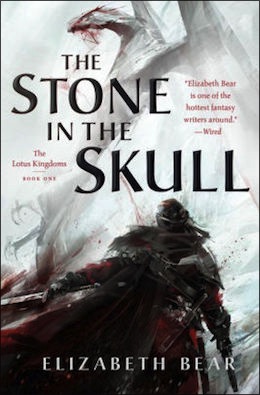

Author Elizabeth Bear returns to her critically acclaimed epic fantasy world of the Eternal Sky with a brand new trilogy. The Stone in the Skull—available October 10th from Tor Books—takes readers over the dangerous mountain passes of the Steles of the Sky and south into the Lotus Kingdoms.

The Gage is a brass automaton created by a wizard of Messaline around the core of a human being. His wizard is long dead, and he works as a mercenary. He is carrying a message from a the most powerful sorcerer of Messaline to the Rajni of the Lotus Kingdom. With him is The Dead Man, a bitter survivor of the body guard of the deposed Uthman Caliphate, protecting the message and the Gage. They are friends, of a peculiar sort.

They are walking into a dynastic war between the rulers of the shattered bits of a once great Empire.

Read chapter two below, but first head back to the beginning with chapter one over on the Tor/Forge blog.

Chapter 2

Mrithuri awakened in soggy silks and knew the rains were coming. Her bedclothes dragged at her skin as she arose from the softness of her pallet. The impression of her narrow body remained in damp cotton and wool batting beneath its tufted cover.

Her mouth was dry and her limbs aching. She felt heavy, cramped, wool-witted, as she could not afford to be. She drifted through the predawn dimness in her nakedness. Knotted rugs of strong-hued wool and tiles of gold-veined indigo lapis lazuli warmed and cooled her soles by turns as she crossed to the window. The draperies were near-transparent layers of silk crepe in blue and violet and tangerine hues like dawn. They stirred over the pierced stone lattice. Mrithuri drew them aside with a hand still naked, soft-fingered, and merely human for now—decorated as it was only with elaborate stained patterns of henna.

There were no guards within Mrithuri’s chamber. Her bhaluukutta, Syama, lay before the door, as tall at the shoulder as a big man’s chest, and twice as heavy as that same man would have been. The bear-dog’s eyes were open, but her head lay on her paws. Syama was better than any human guard. She could not be blackmailed, and she could not be bribed.

Mrithuri’s servants slept lightly. Yavashuri, her clever middle-aged maid of honor, and Chaeri, a hypochondriac maid of the bedchamber, had already rolled from their thinner and less sumptuous pallets along the wall by the time Mrithuri reached the window. She ignored their movements as she leaned forward, veiled in her unbound hair. She wished to cherish the self-deception of privacy for a few moments longer.

Her chamber overlooked the gardens. The white lattice and the rail of the balcony beyond framed a view like a Song silk-scroll watercolor. Whorls of mist caressed the gnarled boles of ancient cassia and almond trees, lay thick across planting beds. The trees would soon drip with blooms—pink or gold for the cassia, delicately blushed white for the almonds. The beds would surge with helleborine and lilies between their banks of rhododendron and laurel. But all were naked to the summer heat for now.

And for now the sky above was transparent, and the killing drought of summer had continued unabated for so long that Mrithuri had to remind herself that other weather was possible. She took another breath of moister air. She turned her attention to the northern horizon, which showed a bright fine demarcation as the Good Daughter, Sahar, whisked her spangled drape off the face of the sky, leaving the brilliance of her Heavenly Mother, the sacred river, unveiled in the sky as on the earth.

There were no clouds to the east, yet. The sea lay west, and the winds came from the west, and weather came from the west. But the storms that made a thriving city and agriculture possible, here in the heart of the arid lands—those came every year without fail from the east, and Mrithuri as rajni and priestess could feel their herald in her bones.

Mrithuri stood in silence and watched the day brighten toward nightfall and the mist burn off. The edge of the veil slid higher, revealing indigo sapphire lit by a hundred thousand million stars as fat and sparkling as the diamond band restraining a rajni’s hair. If it weren’t for the mist cloaking the gardens below, Mrithuri could have looked down and glimpsed the broad expanse of the earthly manifestation of the sacred Mother River Sarathai from the edge of the garden-hung roof above. But as she raised her eyes to the heavens, the black disk of the Cauled Sun set in the south amid its nest of transparent silver flames and the celestial manifestation of the river’s full glory was revealed overhead. The sky and the gardens brightened and the evening blazed.

Only the brightest stars could shine through the dark of day, dimmed as they were then by the Good Daughter’s shawl and the silver corona of the Cauled Sun. By night, however, the whole vast twisted arch of the river of light across the sky’s meridian lay revealed. Its brilliance glowed down from the vertex of the sky, wreathed in gleaming mist as befitted the heavenly extension of the river called Imperishable, called Daughter of Mountains, called White-Limbed, called Faithful, called Unmanifest, called Plaited, called Gilded by the Moon, called Peerless, called Mother of Bread.

“Your Abundance?” the lovely girl Chaeri said, calling Mrithuri from her reverie. The title of courtesy amused Mrithuri, though she hid her smile: it was a silly title for a virgin rajni. Even when that rajni was also a priestess, and the personification of the great Mother River on earth, as the Good Mother was her personification in heaven.

Mrithuri turned from the window before the mist was fully lifted, aware belatedly of the chill that had prickled her skin. The first cool evening of the season. Yavashuri held out a heavy robe of embroidered charmeuse. Mrithuri slipped into it gratefully, stretched her shoulders until the spine between them cracked.

Chaeri limped over as if her joints hurt her. She lifted Mrithuri’s sandalwood box, large enough that the girl needed both hands to hold it. She raised it up despite Yavashuri’s frown of displeasure, and something heavy slid inside. The ache in Mrithuri’s joints itched for the solace within, but it must wait.

“Not this morning,” Mrithuri said, and was proud of her self-discipline.

No one will know, Chaeri’s eyes said, as she lifted the lid. But Mrithuri turned briskly away, despite her aching heaviness. A good mother saw to her children first, as a good daughter saw to the needs of her mother. As the earthly avatar of both Good Mother and Good Daughter, Mrithuri could not betray that trust on a night when she felt the requirement to fast in her blood.

Mrithuri spoke the words, then—the words that would begin her yearly silence, except for the necessary song and prayers. “Tonight will come the rains,” Mrithuri said, her bones ripe with the knowledge imparted upon a true sister of the sacred river, a true daughter of a true raj. Even the discomfort of a fasting morning could not entirely dull the sense of the Mother River’s constrained excitement surging through her. The river was hungry, after the long dryness. And today she anticipated the feast.

Mrithuri’s women shared a glance. It was early in the year—very early!—and so many things would not yet be ready for the rains. But the sky did as it willed, and Mrithuri was only the messenger. They bowed, accepting what she said.

Mrithuri heard the faint whispering, a susurrus of voices from within the pierced interior walls. The voices rose to song, an unaccompanied chant that rang through the rajni’s apartments as the cloistered nuns who moved through passages within the walls sang out their morning prayers. It was a sweet, powerful sound—so many clear women’s voices intertwining—but today, without the solace of the box, Mrithuri winced in headache.

She hid it, as befitted a rajni. She closed her eyes and bowed her own head over her folded hands and—with her maids of the chamber— sang to them in answer her praises of the day, and of the rainy season come again.

* * *

After the morning plainsong, Mrithuri suffered herself to be bathed and coiffed and robed quite elegantly, in honor of the changing season. She wished she’d had the wit to realize how soon the rains would be coming, and eat something substantial before bed. But it was too late now. She would fast until after the ceremony.

Chaeri and Yavashuri closed Mrithuri’s snake-collar about her throat, and slid into place the serpent’s head, attached to the flexible blade that curved within and locked the jewel in place. Her narrow hands vanished into the armatures of her fingerstalls, their long curving oval nails glittering with patterns of ruby, orange sapphire, and diamond. Her wrists shimmered with slender glass bangles that clattered and chimed. Her brown arms, seeming even more slender above the heavy drape of bracelets, were left bare to show the elegant intertwined outlines of sacred bull, tiger, elephant, dolphin, peacock, and bearded vulture that had been inked on her skin as she progressed through her training in the priestess mysteries.

That had been five years before, on her nineteenth name-day, and Mrithuri had managed—so far—to remain unmarried. Someday, she knew, the lines would feather. Her courses would cease, and the skin of her limbs would slacken and lose its tautness. Perhaps on that day her counselors would finally cease their importunings that she marry and get an heir.

She allowed Yavashuri to smooth the weight of her patterned vermilion drape over her shoulder and fasten it to her cropped silken blouse with a heavy jewel. Her belly would be chilly, but the dress would flaunt the red-gold glow of the Queenly Tiger in her navel. Perhaps the radiance of the jewel would remind her counselors and sycophants, after all, of who truly was rajni. Even if, being a woman, she could not sit upon the Peacock Throne of her grandfather—and of his grandfather before him, who had been the legendary Alchemical Emperor and unified the kingdoms of both Sarathai and Sahalai into the Lotus Empire, which had endured not a dozen years after his death at the age of one hundred and eleven.

She rubbed her aching hands together and thought again of her scented sandalwood box, and the relief it contained.

The servants of her chamber seated her upon a stool, then powdered Mrithuri’s feet with gold dust and decorated her bare toes with rings and jewels. They helped her to rise again and she stood under the weight of all that cloth, all that gold.

The falling scarf of her drape demanded she hold her shoulders back, and high. The headdress demanded the same of her neck and skull. She took a breath and settled into herself; the posture of a ruler.

She stepped from her chambers accoutered and constrained, every inch a rajni. Syama levered herself up with agile strength and followed, light rippling on the black and gold brindle of her coat as she passed before the windows. This was still Mrithuri’s private wing of the palace, where the rajni and the cloistered nuns lived. Only her household, and certain very specially honored guests, were allowed to tread here. Only the servants of her body would ever see her other than in her mask of majesty.

Unless she deigned to marry after all, she mused, with a faint secretive smile.

Her people paused and bowed as she passed, eyes downcast. As always, it struck Mrithuri as a tremendous waste, to spend so much time and money on making her resplendent when no one was allowed to look at her directly. Maybe she should take a husband. Just so somebody would be able to appreciate properly the results of all this fuss. The rest of her court spent all their time staring at her gilded toes.

She walked sedately, in deference as much to her headache and the heavy dress as to her rank, and restricted herself to the gliding steps that would keep all her finery balanced. The scarf of her drape flowed out behind her on the slight breeze of her passage, while Syama padded silently at her heels, ever-watchful. Stout, dour Yavashuri and voluptuous, round-hipped little Chaeri followed her at a respectful distance. Their eyes would be downcast too, but they were mistresses of watching for any slipped hair or trailing hem through their own lowered lashes. The nuns in their cloister within the walls followed also; Mrithuri glimpsed their silver-threaded white cotton gauze veils and heard their slippered footsteps through the latticed stone.

She hated shoes quite passionately. She would have never made a nun.

Courtiers and the rest of her entourage—the people who fancied themselves important—awaited her beyond the golden gates that guarded the entrance to the rajni’s household. They fell in on all sides: counselors and sycophants, priestesses and courtiers, ambassadors and—for all she knew—assassins. Some were her favorites; some only thought they should be. She kept her measured pace and did not speak to any.

Nor did they speak to her. Word had passed with the morning plainsong that today was a day of ritual. To distract her now would be to disturb her meditation. Which she probably should be paying attention to, though it was hard to do so as they passed the turning to the throne room and its storied, unoccupied chair. No one had sat in it since Mrithuri’s grandfather’s death. No one had dared.

She squinted against the glare as her centipede chain followed her out into the bright morning sun. Instantly, a silken shade was raised over her—a blessing, as she couldn’t shade her eyes with her heavily decorated hand without risking putting one of them out on a finger-stall, and it would have been a break in decorum to do so anyway. She walked across smooth cobbles still cool with morning, down the narrow path bordered with jasmine and the imported, coddled ylang-ylang, neither of which were yet in bloom. It didn’t matter that they were still scentless. The spice and incense of the court atmosphere followed her into the fresh air of morning, carried on her clothes and the clothes of her entourage.

She wished she could put on a tunic and trousers, shed all these bridal fripperies (elaborate enough to weigh down any flighty fiancée), and go skipping down the path at a run. It amused her to think of all the courtiers rushing after her, out of shape and out of breath. She bit her lip against the giggle.

Mrithuri made herself instead stop decorously at the edge of the constructed rise her palace sat upon. The man-made hill elevated Mrithuri’s home safely above the yearly deluge while allowing the rajni to remain within sight of the sacred river. No dike had ever been raised that could hold back the Sarathai when the floods began, fed as they were by the monsoon and by the meltwater flowing down from the Steles of the Sky, where spring began much later than in the hot lowland countries.

Mrithuri turned her gaze up to the stunning vaulted sky above, the vast cool shining of the Heavenly River with its curving bands, the coppery rim of a full moon rising heavily to the north. No clouds yet, and the depths of the sky were as deep and transparent as the eye of a dragon.

Her entourage held its breath around her. She turned thoughtfully, and was gratified to catch the eye of Ata Akhimah, the Aezinborn Wizard who was Mrithuri’s doctor, the court astronomer, and her closest adviser and friend. She wore flowing black trousers and a loose, white tunic, sleeveless to show off her velvety complexion and her muscled arms. She didn’t avoid looking Mrithuri in the eye. Silver bangles chimed and ivory bangles clicked as Ata Akhimah raised her hands. “Open the gates!”

Three footmen sprinted down the hill toward the tall wrought gates that dominated the gap in the white stone wall. Watching them left Mrithuri envious again. They wore their long, full, white cotton skirts wrapped up between their legs into a sort of blousy trouser and ran without impediment, and their heads probably didn’t hurt. Unless they’d been drinking a little rice beer the night before.

She thought longingly of the ivory-and-jet inlay of her sandalwood box. Chaeri would have it for her when this was done. She just had to get through the fast and the ritual, and she could have her breakfast and her tea and her bite as soon as the rain came down.

The runners reached the gates. They were about to raise the bars and turn the keys when a loud male voice cried out, “Your Abundance, Your Abundance, I must speak with you immediately!”

That the shocked intakes of breath on every side were the only answering sound was a testament to the self-discipline—or perhaps the devoutness—of Mrithuri’s court. They all turned, except Mrithuri. She kept her eyes on the water gate, and tried to keep her mind on the ritual. She’d been so successful so far, after all. Besides, she could see who was coming out of the corner of her eye, and she wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of responding.

She didn’t need to. Yavashuri had already detached herself from the procession. Without speaking a word, she had touched two burly men on the elbows and led them over to intercept the blasphemer.

The man who swept toward the royal procession was tall and broad. His tidy beard and thick dark hair were streaked with gray. The neck that protruded from the open collar of his long linen blouse was broad and thick. Over the blouse and his trousers he wore a saffron-colored tunic heavy with embroidery and goldwork along the open plackets. He was not quite moving at a trot—that would be beneath his dignity and authority—but his stride betokened no little impatience.

It was Ambassador Mahadijia, scion of the household of her troublesome cousin Anuraja, who was the son of Mrithuri’s grandfather’s sister, the king of the rich port city of Sarathai-lae, and a constant irritation.

Syama took two long steps to come up beside Mrithuri. The bear-dog curled her lip over her long, yellowing canine. She did not moan her threat, as was the habit of her kind. Her lopsided snarl was utterly silent, and utterly convincing—from the flash of her fang to the furrow of her brow.

Mrithuri put a jeweled hand on the bear-dog’s shoulder to restrain her.

“Your Abundance!” Ambassador Mahadijia called again. “It is imperative that I speak with you at once!”

He stopped, mirrored sandals flashing, as Yavashuri and her enforcers stepped before him. Yavashuri had been Mrithuri’s nurse. Mrithuri did not need to turn to know that Yavashuri was raising a finger to her lips, a stout little tiger facing down a much, much larger bear.

There was a flurry of movement—the enforcers closing ranks— and over his protests Mahadijia was bundled away. They would not lay a hand on him, Mrithuri knew. The ambassador’s person was sacred. They would just present an immobile and rather nimble wall, and keep edging him back until he got the idea that he was not currently welcome here.

Weren’t ambassadors supposed to have some sort of skills involving tact and diplomacy? Mrithuri stifled a sigh. Anxiously, she wondered what could possibly have been so damned important that it was worth risking the displeasure of the Good Daughter. Or possibly Mahadijia was just too daft to realize what had been happening.

“Your royal cousin,” he yelled from beyond her line of sight, “will hear of this outrage!”

Mrithuri still never turned. She gestured with one glittering hand for the opening of the gates to continue.

It was done, in silence except for the faint rubbing of heavy, well-oiled metal. The ambassador’s voice faded away. And there, at the bottom of the path, flowed the mighty river, Thousand-Named, Ship-Bosomed, Gilt With Lotuses.

She was certainly gilt with lotuses now. Great mats of vegetation like floating islands clothed her silt-pale flanks. The earthly river was as white as the heavenly one, though less shining, the water as opaque as the milk of the sacred cattle it so resembled.

The lotuses were new this morning. They, too, were a sign of the rain returning—independent of the rajni’s infallible premonitions. They bloomed for the first time each year on the eve of monsoon, and were the first flowers to return to soften the breast of the Mother River, and the land she watered, after the summer’s heat baked all the winter’s petals dry.

Mrithuri strained her eyes through the last swirls of mist slowly burning off the water. The Broad-Bosomed was thick with boats, but they stayed respectfully far from the sacred sweep of the lotuses. The rajni could make out the colors of augury splashed in the unfolding petals—pinks and whites and ivories, yellows and blues, the rarer greens and oranges and lavenders. And there, like a prick of blood among the paler colors, she glimpsed what she had been afraid to see: one single lotus, bobbing with the others, red as a beating heart.

Was there a black one? Was she that unfortunate? Not near the red, at least. Mrithuri resisted the urge to stand up on tiptoe, which did not befit the dignity of a rajni. By the Good Daughter’s lost lover, the light reflecting off the water was no friend of her headache.

There. Off by itself, like an ink spot on paper. One splash of black on the creamy surface of the river. Unless it was a violet so dark as to seem black, which was nearly as unsettling.

Well. At least the mere possibility of a dangerous augury did not mean that the fates would, perforce, supply its completion. Mrithuri looked over and saw Ata Akhimah glancing at her worriedly again. Their gazes brushed. The Wizard nodded and turned away.

She had not been raised or educated in Sarathai-tia. But she had lived here all of Mrithuri’s life, and then some. She knew her duty, and she knew her adopted religion very well indeed.

Mrithuri took a breath to settle herself and tried not to think of the heavy sliding inside her box. She tried not to think of red lotuses, or black. She focused her eyes a little closer, instead, and smiled. At least, there at the bottom of the path, was the gilded stair. And beyond the stair, her old friend Hathi waited for her, hung as Mrithuri herself was in tangles of silk and ropes of gold.

That was where the resemblance ended. Hathi’s great chinless mouth was at the level of Mrithuri’s crown. Her pale, tan-spotted ears fanned wide as she caught sight of her friend, and her trunk raised high. She shifted her weight impatiently, causing the belled chains on her ankles to chime.

No one had ever been able to convince the white elephant that she was a sacred symbol of the Mother River, and that she ought to comport herself with dignity. And she had never quite figured out why her friend, the young princess who used to run to her after meals with smuggled sweets leaf-wrapped and tucked into the pockets of her tunic, had become so stiff and formal in public as they aged.

Or maybe she did know, and just didn’t care what people thought of dignity. Hathi was old, after all; she’d been born around the same time as Mrithuri’s grandfather, and had been a naming-gift to the young prince then. And the old, Mrithuri thought, often had little use for the sorts of time-wasting pomp and ceremonies indulged by the young.

With a hand gesture, Mrithuri bade Syama wait with Chaeri. The bear-dog flicked her ears in disagreement, but did not otherwise protest, and settled in beside the maid-of-the-bedchamber with a show of forbearing.

Mrithuri mounted the little stair, balancing herself with her palm against the rail. She couldn’t close her hand on it, not with the fingerstalls on. Fortunately, she was well-schooled in achieving her old friend’s back even with all their clutter hung on them—and Hathi’s rig was designed to be climbed by someone even more encumbered than Mrithuri was.

She settled herself sideways on the shoulders, stroked the elephant’s warm, dry hide, and concealed a sigh. What they called a white elephant wasn’t, really. Even scrubbed and exfoliated, Hathi’s hide was a dull pewtery color, though much lighter than those of most of her kin. Her dressers made up for this by whitewashing the beast—quite literally—in baths of limestone water. (The whitewash also helped to protect her from sunburn—a real consideration, given the paleness of her hide.)

Hathi bore Mrithuri down to the river with a gentle, swaying stride.

Elephants only appear ponderous to the uninitiated. From her perch on Hathi’s back, what Mrithuri felt was a light-footed, rolling gait that reminded her of a ship. The elephant’s bells jangled pleasantly, and she reached her delicate trunk-tip up to inspect her rider carefully. Their escort followed behind as the white elephant bore her rajni down to the sacred river’s muddy bank. There, they paused.

Mrithuri knew it was because Hathi had sensed the shift of Mrithuri’s weight, and so known at what place to hesitate. But she also knew that to the crowd gathered on the bank, it seemed as if the elephant had come to some decision, or was following an invisible sign. Well, perhaps that was accurate.

The Mother River, the lady with all her names, stretched before them as broad and placid as could be imagined. She was narrowed with the dry season, and still Mrithuri could barely glimpse her farther bank. Slow-moving, knotted islands of green vegetation floated on the gentle current. She was clotted with long, low boats, on this auspicious evening, and the boats were loaded with women robed in their finest, and with men in loincloths poling gently to hold position. They had all come out to see Mrithuri, and Hathi, on the eve of the rains—and to witness with their own eyes the augury of the coming year.

A snout like a toothy longsword broke the water several body-lengths out, followed by an almost-eyeless head and the muscular curve of body and a sharp, upright pectoral fin. A bhulan: one of the Mother’s blind dolphins, swimming on its side as they did so commonly.

A good sign. A sign of the Mother’s pleasure, that the sacred swimmer—twin to the one marked on Mrithuri’s forearm, and twined with a tiger there—would come in among the boats of so many observers, gathered to mark the auspiciousness of the day. And there were any number of boats—from the daily fishing vessels, to the longer, lower scows with their equally low cabins and their free-board so slight that they looked like nothing so much as roofs floating independently along the water. Those were houses, and the people who fished from them lived on them, entire families in one tight little floating room, mostly underwater.

All the river’s people, summoned by the blooming lotus, had gathered to watch the ritual and witness the augury.

Mrithuri unpinned her drape at the shoulder, willing herself not to fumble despite the awkwardness of her fingerstalls. She rose up on Hathi’s shoulders and balanced on her gold-dusted feet as she unwound the ells of cloth from around her waist until she stood up only in her blouse and petticoat and so many sparkling heaps of jewels. She handed down the drape and the brooch to Chaeri just as Yavashuri returned, looking even more cross than usual for this hour of the day and no breakfast. Syama sat back on her haunches and laughed up at Mrithuri and Hathi.

Hathi reached her long nose over, and fondled the bear-dog’s ear. The bear-dog ducked good-naturedly.

More boats swept along the river, assembling nearby. These were more of the fishing craft, poled by men already stripped down to loincloths and headdresses, though the heat of the day was already cooling. Though the Cauled Sun gave but little light, it produced heat in abundance.

Mrithuri watched them come, and found the silence of everyone a little eerie. A babe cried, and no one hushed it. She pressed the jeweled nail-tips of her fingerstalls against her thighs to seat the damned things more firmly on her digits and rocked her weight forward, onto the balls of her bare feet.

Hathi knew what that meant. With an amused flick of her pink, spotted ears, the elephant moved forward, just exactly as if she had decided—spontaneously—on her own to do so. She crouched slightly going down the bank, flexing her hind legs to keep her back level. Mrithuri, bejeweled hands upraised in a spectacle of benediction, reflected that she’d known a lot of human beings less considerate of their fellows than this elephant.

Hathi slipped into the water without so much as a splash. The only ripple she raised was where the sacred river’s current parted around her thighs, and then her chest, and then her mouth, which grinned with amusement at the trick she and her old friend Mrithuri were playing on all these gullible ones. She slid into the river like a fine lady into her milk bath, and the parts of her body below the boundary of air and river vanished as completely as if she has somehow stepped into a flat surface of mother-of-pearl. Except for their own ripples, the river had gone mirror-still in a breath-held absence of wind.

Mrithuri could feel through her soles the moment when Hathi’s feet lost contact with the rich white river silt, and she was swimming. There was a strange buoyancy, as if Mrithuri stood on the deck of a barge. A large, warm barge, with a play of muscle beneath a hair-bristled hide.

Mrithuri pressed down with her toes. Hathi, with every appearance of independent decision, raised her trunk, exhaled, and submerged completely. The elephant’s silken trappings billowed around her, nearly lost from view in the milky river. But Mrithuri could still feel Hathi laughing silently through the soles of her feet as the sacred water lapped over the elephant’s back, and as the sacred river washed the gold dust off Mrithuri’s feet. A small sacrifice, that, and vanished in no more than a swirl of glitter.

The river was warm at the surface, and she—she, Mrithuri, rajni of Sarathai-tia, was gliding across it as if on oiled wheels. Like a bird across the sky, borne on an unseen wind.

Hathi exhaled again, further lifting her trunk, and the waters rose higher. They swirled around Mrithuri’s calves, then her knees, whipping the wet silk of her petticoat between her thighs. That it stayed on at all was a testament to the weavers of the laces.

The water was colder as she descended. Warmth could not penetrate far below the surface, and the deeper currents reminded her that the Sarathai had its source high in the snows near the Rasan summer capital of Tsarepheth, where the Rasani Wizards kept their famous Citadel.

Mrithuri fought the urge to hunch against the chill. It was all about keeping up appearances, this annoying business of being a rajni. At least the cold eased the ache of fasting in her head and joints.

Something tickled and tingled her skin. She thought she knew what. She crouched down, plunged her hands under the water, and— awkwardness of the fingerstalls and all—hooked hold of the raised handle at the neck of Hathi’s harness. Now the water broke against Mrithuri’s chest. The elephant’s gentle forward momentum was enough to swirl a muddy ripple around the rajni. She held on, carefully—to fall now would be a terrible omen—and just as carefully kept her face impassive and her coifed head above the current.

Her whole heart and lungs seemed to vibrate with a throbbing unheard cry. The blind dolphin’s song was a thrill reverberating in all the empty spaces of her body. She had seen one; she could feel dozens. Their voices shivered in the nerves of her teeth, the minuscule bones anatomists like Ata Akhimah said lay deep inside her ear.

Along the margins of the Mother, where the current slowed and the banks sloped down, that was where the sacred lotuses grew—in their profusion, in their sweep of many colors. In their grace and fineness.

Hathi responded to the shift of Mrithuri’s weight, the curl of her toes. She swept back toward the bank, high up from the landing, where the sacred lotuses bobbed and swayed in the gentle flow of a river too broad and deep to hurry on her way. The boats had left a path for her and she kept to it, trunk uplifted as if she were as conscious of the need to put on a good show as ever was Mrithuri.

Hathi bore her away from the black lotus, segregated as it was from the others. That was a small relief at least. That single splash of crimson among all the pale pastels and sunny yellows and oranges was less avoidable. The red lotus had grown in the sacred bank with the others, which had not happened in Mrithuri’s memory, though she knew its varied meanings. Mrithuri could still see it, even from here. The color stood out starkly against the blues and peaches and ivories and whites.

She heard the stir as those of her people who had not already spotted the bloody splash noticed it, the petals as broad as a serving plate lifting and falling on each of the river’s slow swells. They did not speak, but they shifted and sighed. They might as well have shouted, when even the wind held its breath like this. Red. A red lotus!

Its mere blossoming was a warning, and a portent. If Hathi chose it . . .

Mrithuri shifted her weight to urge Hathi away from the single scarlet bloom. Theoretically, the sacred elephant was supposed to make her choice without the rajni’s command. But if she was honest with herself—herself at least, if not her people—Mrithuri had been performing this role since she was her grandfather’s granddaughter and not rajni in her own right at all, and she suspected that the bond between herself and Hathi was such that she couldn’t have kept her opinions from the elephant.

For the first time in their association, the elephant did not seem to understand Mrithuri’s unspoken hints. Hathi kept swimming into the bank of lotuses, and as Mrithuri watched with a settling helpless chill, the elephant reached out, unhesitating, and pulled the stem of the single scarlet flower dripping from the mud.

The pit of Mrithuri’s stomach dropped, and a cry went up from the boats and from the shore as hours of pent-up, sacred silence was given vent. The people did not even know yet if they cried out with joy or sorrow; the emotion they felt would not be defined for them until the court astronomer had considered the augury. They cried out largely because they could not stay silent an instant longer. They cried out in the relief of crying out. That was all.

Mrithuri settled back on her heels, unconsciously, and this time Hathi sensed her movement and acknowledged it. The elephant ceased her progress and floated, moving gently to stay in one place. She waved the scarlet flower to and fro at the end of her trunk, playfully, the long trailing stem flicking water and mud into the crowd.

The rajni must have sat still too long, because Hathi turned back to shore of her own volition and, having swum the little distance to the cobbled ramp, began gently to climb. The motion startled Mrithuri into thought, at least.

You’re a rajni, Mrithuri. Act like it.

She gathered herself, and as Hathi emerged from the river, streaming muddy water and all her whitewash dripping down, Mrithuri stood and spread her arms wide. She had schooled the shock from her face, and managed—she hoped—a mask of queenly impassiveness as Hathi gained the bank, still waving her scarlet lotus cheerfully.

The royal astronomer stood forward, reaching out to accept the lotus. Hathi teased her with it, holding it high. Ata Akhimah was no fool, and turned her gesture into one of arms reached upward in benediction.

Give it to her, you great goof, Mrithuri thought fiercely. Hathi relented, and placed it in Ata Akhimah’s hands.

“The red lotus!” she said, buying time. “My rajni, a potent portent indeed! For its color presages blood.”

A murmur swept through the crowd. Mrithuri lowered her own arms and kept her attention on Ata Akhimah. The Wizard bent her head to study the lotus, picking through the petals with care, examining the stamens and pistils. Mrithuri clenched her jaw to keep her teeth from rattling as gooseflesh prickled across her wet skin. The light of the Heavenly River was brilliant, but the evening was still chill.

Their eyes met, queen-priestess and Wizard-doctor. Neither dared frown.

Work your magic, Akhimah, Mrithuri thought. The last thing we need right now is a terrible augury for the year to come. On top of Mahadijia interruptingthe ceremony, that’s not consolidating to my reign.

But despite her foreign name—so masculine in its sound!—and despite her foreign schooling, Ata Akhimah had been long in Mrithuri’s land. She knew a thing or two, and Mrithuri trusted her.

Akhimah winked and turned so that her back was to Hathi, and she faced the assembled crowd. “The lotus that grows by the palace of Sarathai-tia is the reason that palace is here,” she said. “This lotus bloomed here before the Alchemical Emperor united the kingdoms of the Sarathai and the kingdoms of the Sahalai into one Empire. This very lotus, this plant from which we pluck our auguries. Upon whose sacred roots and stems and nuts we sup. From whose sacred stamens we brew our tea. For the lotus is eternal, undying.

“This blossom bloomed white, they say, in those days. It bloomed when all lotuses bloom. But the Alchemical Emperor came here, and sat upon his bank, and saw it—blooming white in its purity, having lifted itself from the mud. We are told that this courage touched the Alchemical Emperor, and so he touched in turn the lotus. And it was the stroke of the hand of the Alchemical Emperor himself that caused it to bloom each year and offer a prophecy.”

She brandished it again, red as hearts-blood, dripping silt water across her ebony fingers.

“This sacred blossom budded in the mud. It rose out of the mud. It grew tall and beautiful from the mud, until it floated on the water and emerged on the bosom of the earthly river, in the light of the Heavenly River, for all to see. This sacred blossom on the bosom of the Mother River reflects the sacred stars that bloom on the bosom of the Heavenly River, and light our nights below.

“And it offers us a glimpse of a happy future now!

“Blood can come from birth as well as death,” Ata Akhimah intoned, with admirable projection. “Here, in the depths of the blossom, there are traces of gold. That presages richness rather than conflict. The Mother has spoken! In the coming year, the auguries predict for our beloved rajni a marriage, and an heir!”

Oh, Mrithuri thought. Well, thanks for that, old pal.

Ata Akhimah lifted the blossom, cupped on both palms, as if she were offering it to the starry river above. Hathi rumbled, as if to say don’t mind if I do. She reached out, plucked the portent from the priestess’ upraised hands, and popped it into her giant mouth, where it disappeared in a couple of casual chews.

Mrithuri kept her face impassive as the elephant began to walk idly up the path. Faster, she urged silently.

The contents of the pierced sandalwood box awaited her attentions. And vice versa, she thought, and hid a smile.

* * *

After Hathi was led away for her bath and breakfast, the nuns within the piercework walls sang Mrithuri back into her chambers. She was shaking with the cold by the time her handmaids pulled her sodden petticoats and blouse off her, dripping sacred, silty river water all over the tiled portion of the floor. The water in the rajni’s private bathhouse was hot—Ata Akhimah had long ago overseen the installation of modern plumbing, with a hypocaust and boilers kept stoked and bubbling. It was a great luxury, and the rajni’s women would have bathed her immediately to get her warm.

Normally, she would have permitted it, too. But the clouds had slid across the heavens as she climbed the steps, and by the time she was back in her own rooms and her women were pulling the stalls from her fingers, a gentle patter of rain had begun to fall. The echoes of thunder rolled distantly, growing louder. The river’s fast, and the rajni’s, were both ended.

Yavashuri was before her at once with a pierced ivory plate loaded with tiny morsels. And Mrithuri’s stomach rumbled in answer to the distant thunder at the smells of cardamom, turmeric, saffron, and cumin. But Mrithuri was impatient, agitated with the augury of the red lotus, shivering with gooseflesh and nevertheless still standing naked except for a rug wrapped across her breasts and then draped around her shoulders. Her fast was doing nothing for her temper, either, as she waved Yavashuri away with ardent hands.

“Bring me my damned box,” she said, and Chaeri scampered off to get it, forgetting in the excitement to limp.

Yavashuri set the food aside and lifted a bowl of lotus-scented tea to her with both hands, ceremoniously. Steam coiled up, but Mrithuri waved it away as well. “I don’t want that,” she said. “You know what I need now.”

Irritably, she rubbed at the likeness of the sacred snake tattooed on her arm.

“It will be a moment, Your Abundance,” Yavashuri said tiredly. “And you are cold and have eaten nothing. The tea will warm you, Your Abundance.”

Mrithuri glanced away, ashamed of herself a little. The craving in her was stronger than cold, stronger than hunger. But Yavashuri, her old nurse, never used her title except as a reproach. And it was traditional to break the sacred fast with this tea, flavored with the stamens harvested from those selfsame sacred lotuses.

She sighed and accepted the cup, glancing anxiously after Chaeri. Relief for her headache and aching joints would come faster on an empty stomach. But the tea was plain, unsweetened and without milk, and should not lessen the effect.

“My pardon, Yavashuri,” the rajni said. “It has been a trying evening.”

While they quarreled, the tea had cooled enough for drinking, and she sipped it. It would do for now.

She drained the cup, but irritably waved away the platter of dainties Yavashuri lifted to her again. She did not want sweets soaked in rosewater syrup, or delicate folded pastries, or dumplings so tiny and crisp they would melt like butter on her tongue. She did not want tidbits of snail sauteed in butter and allium, then skewered and returned to their shells. She did not wish tiny balls of saffron rice and meltingly tender slivers of meat.

She would eat the lotus stems and the sliced and fried rhizomes, as tradition demanded. But first . . . yes, first.

Here was Chaeri now, the big sandalwood box in her hands. The woman handled it carefully, remembering—Mrithuri hoped—that Mrithuri had rebuked her for carelessness not too long ago. Mrithuri would not care to rebuke her again unless she must; that one incident had led to a week of enduring suffering sighs and sidelong, sulky glances.

She reminded herself that Chaeri had a difficult history, and that tolerance was a benediction of the Mother. Chaeri set the box down on a low table and backed away. Mrithuri sank gratefully into the inlaid, square-armed chair beside it. Lacquer and gilt everywhere, the brightness doing nothing for the increasing throb of her headache.

She reached out and stroked the carved fretwork of the surface of the case as her women backed away. Chaeri smiled. Yavashuri frowned. The others were carefully neutral, and the nuns sang on.

The rajni had no secret from the nuns. But the nuns were nothing but secrets. They never left their cloister, and they never spoke to anyone outside the residence of the rajni.

Mrithuri slid the lid aside, very gently. That which dwelt within was not overfond of sudden movements, sudden lights, or vibration.

A faint hiss answered her motion nonetheless.

She waited, then gently reached inside. Now her motions were steady, her gaze calm. If a chill still prickled the flesh of her arms and made her grit her teeth to keep them from clicking, she did not let it affect the dexterity of her hands.

She felt a curve of firm muscle, a cool leathery body. A flicker of questing tongue. Gently, she eased her fingers around the denizen until it was encircled. She slid her fingertips up scales the wrong way, feeling their raspy, feathery edges and careful to touch lightly. There were the heavy muscles of the skull, the softness of the cheeks.

She glided the lid aside the rest of the way and firmed her grip on the serpent within. As she lifted it from its comfortable burrow, her ladies turned away. Except for Chaeri.

The snake was perhaps as long as her arm, though thicker through the body. It was a moss green in color, rich and soft, and upon its long back were delicate, definitive patterns that resembled the figures of brush calligraphy in some complex, unreadable tongue. Its lidless eyes gleamed like jade, and its black tongue flickered, tasting.

“Hello, precious,” Mrithuri cooed to it, holding it behind its heavy jowls quite firmly. It tested her grip, but she managed it. The bulky body was unbelievably strong, and very heavy. The skin felt like the finest leather.

The door to her private chamber slid aside in its runners.

She didn’t drop the snake. She pulled its face away from her own, and raised her chin to look at Ata Akhimah.

The Aezin Wizard slid the door shut behind her without turning back to look at it. She had traded her earlier clothes for a halter of white linen and white linen trousers, worn under an open black robe that swept the floor behind her red knotted hemp sandals. She sighed, and crossed her arms over her chest in the wide sleeves. Her bangles clattered, some glittering, some the yellow-white of bone.

The Wizard said, “It would not do to become too reliant on that Eremite venom, Your Abundance.”

The serpent seemed to be growing heavier. Mrithuri allowed the mass of its body to rest upon her lap, keeping control of the head only.

“She is as dependent on me as I am on her,” Mrithuri replied.

She pushed aside the bath rug, and applied the serpent’s fangs to the left side of her chest, just above the small swell of her bosom, next to a ragged row of a dozen pinprick scabs surmounting layers of tiny white scars. The snake, discomfited by the noise and argument or perhaps by the chill of her hands, was all too content to oblige her. It bit hard and bit deep, a sharp pricking pain followed by the deep, spreading feeling of burning. Mrithuri felt the jaw muscles work against her fingers. When it stopped, she pulled the snake away.

A bubble of blood formed on the snake’s mouth as its jaw closed. Warmth moved through its cool flesh. It had fed, and would be sluggish now. She cradled it close against her, still controlling the heavy, triangular head.

She leaned back in the square, uncomfortable chair and released herself to the burning. It crawled through her from the site of the wound, a slow painful warmth that pulled the chill from her flesh far more effectively than the tea had done. A trickle of blood wound down her breast as she relaxed. The aches in her joints extinguished themselves. The pounding in her head began to recede. She closed her eyes and enjoyed clarity, energy, the feeling of well-being that followed.

When it had settled in, Mrithuri opened her eyes again. Gently, she replaced the satiated serpent in her den, beside her sisters. She closed the lid, making sure the air flow would be unimpeded, and waved Chaeri to her with a negligent but much more relaxed gesture than previously. When the girl had taken the serpent away, her long brown-black curls swaying with her walk, Mrithuri looked around with a sigh. What had Yavashuri done with the damned breakfast?

Oh, there she was with it. She had set it on a slightly larger table across the drawing room, with the remains of the tea, and was pulling up a second chair.

Mrithuri stood, her limbs light and full of energy. Yes, she thought she could face breakfast now. “Did you find out what that damned Mahadijia wanted?”

“No. But it’s nothing good, I’m sure of it,” Ata Akhimah replied, studiously turning her eyes to the barren gardens beyond the windows. “Your cousin Anuraja is a weasel.”

Mrithuri looked down, and tugged her bath rug back into something resembling modesty. “Weasels are useful. They keep the rats and cobras in check.”

Akhimah snorted. It was as close as she came to a laugh. Mrithuri had not known enough Aezin to guess if that was a cultural trait or a particular one. It was true, though—tensions between cousin Anuraja, to the south in his kingdom of Sarathai-lae, and cousin Himadra, to the north in his kingdom of Chandranath, helped to keep Mrithuri and her own little speck of land safe. And as long as she could keep juggling both of them and marrying neither, she stood a good chance of maintaining the independence of her corner of this crumbling empire.

“Sit and eat with me.” The Wizard’s bangles chimed as she gestured. “Every discussion is better over breakfast.”

Mrithuri sat. All the thought about balancing terrors reminded her of something. “No word from your old master yet?”

The Wizard, ladling mango puree over a dish of rice, looked up and frowned. “ ‘Mentor,’ I would say, not ‘master.’ She and I were of different schools, and I got my training at the University.”

“Someday you’ll explain to me what the difference between Aezin and Messaline Wizardry is.”

“It would be faster to explain the commonalities.” Ata Akhimah smiled. “We—my school—are healers, architects, geomancers. We build and repair. The Wizards of Messaline also build things, some of them, but what they build are automatons. Or they raise the dead, or see the future . . . it’s really not the same thing at all.” She waved a wrist dismissively, chiming. “Were you hoping she would come herself ?”

“I was hoping she would at least send help,” Mrithuri admitted. “Or some kind of a message. Something to aid us. Her reputation, after all, wraps the world. She might know something that would give us an advantage over the neighbors. I don’t expect her to come herself. I know the Wizards of Messaline do not like to leave Messaline.”

Mrithuri looked down and pushed a morsel of baked fish across her plate. Nothing appeared appetizing.

“Be patient,” Ata Akhimah advised. “I foresee that you will still have a kingdom and still be a rajni when her messenger arrives. Red lotus or no red lotus. Your Abundance.”

Mrithuri rested her forehead on the palm of her hand. “From your lips to the Mother’s ears, Akhimah.”

Excerpted from The Stone in the Skull, copyright © 2017 by Elizabeth Bear.