In Which We Take A Roll Call of the Valar and Their Maiar Compatriots, and Melkor Rearranges the Furniture

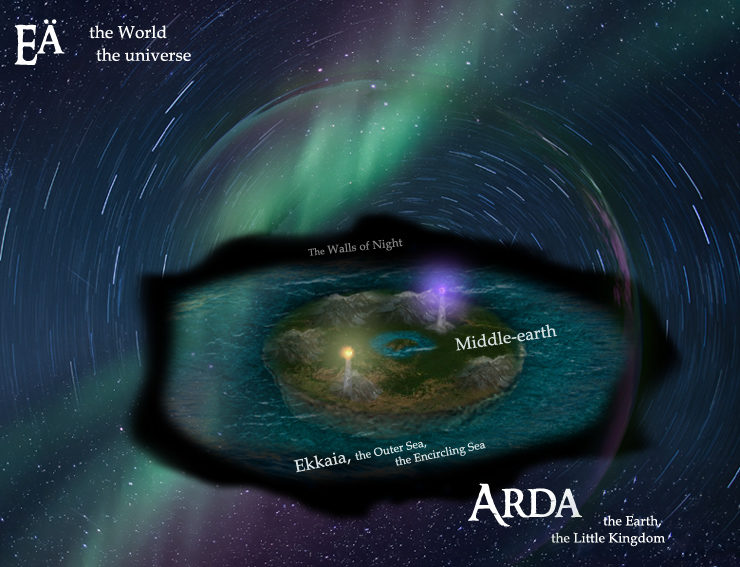

The Valaquenta—the “Account of the Valar”—is a sort of cast list for the earliest days of the Valar in the newly minted universe of Eä, and also an introduction to another group: the Maiar. Although there’s no real action there, there is some delectable stage-setting and real estate talk.

Then we’ll start right into the Quenta Silmarillion, the “Tale of the Silmarils.” Its first chapter, “Of the Beginning of Days,” describes the earliest conflicts with Melkor, which involve some impressively large (if glaring) floor lamps, followed by some cool arboreal nightlights, and how the face of the world is changed forever.

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Melkor – ex-Vala, Public Enemy Number One

- Manwë – Vala, air traffic controller

- Varda – Vala, illuminator

- Ulmo – Vala, oceanographer

- Aulë – Vala, smith and groundskeeper

- Yavanna – Vala, horticulturist

- Mandos – Vala, judge, professional brooder

- Nienna – Vala, professional mourner

- Oromë – Vala, hunter, animal wrangler

- Tulkas – Vala, MMA fighter

Valaquenta

After a two-paragraph recap of the Ainulindale, we are presented with fifteen Valar, the mightiest of the Ainur who have come down into Arda. That’s thirteen Valar + Melkor + one laughing, ruddy-faced latecomer (no, not Santa Claus) who didn’t even originally sign up for the job.

Now, there’s no need to memorize all the names in the Valaquenta, because it’s a hell of a lot, and because some almost never come up again. But some have notable roles to come, and these are the ones to start impressing upon your mind:

Manwë (MAN-way), of course, is at the top of the list. He’s the master of the skies and air, “first of all Kings.” He is, in fact, the very basis for the idea of kingship in all that follows. We’re also told that he is closest to understanding the mind of Ilúvatar and had even been the “chief instrument” in that second theme in the Music of the Ainur—the one that was raised to counter Melkor’s initial discord. These are no small things! Remember, these two are supposed to be brothers, and we know it eats Melkor up inside that he’s not given Manwë’s title. Manwë will soon dwell with his wife way up in a tower aerie on the tallest of the Earth’s mountains, while hawk- and eagle-shaped spirits come and go, bearing news far and wide.

Varda, Lady of the Stars, is beautiful beyond description and has, literally, the light of Ilúvatar all up in her face. And that’s an amazing thing; when people look at her, they see a reflection of that transcendent glory. Varda is notable as the Ainu who makes all the freakin’ stars in the universe from her part in the Music. (And it won’t be the last time she upstages everyone, either.) Manwë is Varda’s husband, and together they make the ultimate power couple in Arda.

We’re also told that of all the Valar, Elves will adore her the most. And because Elves love to have a bazillion names for things, they won’t even call her Varda much; to them she is usually Elbereth the “Starkindler.” Readers of LotR may recall the many times that name gets invoked like a prayer in times of need—by Legolas for sure, and even by Sam and Frodo.

Wait, we’re not finished with Varda yet! The drama deepens when we learn that she actually rejected Melkor. This was back before the Music of the Ainur. And lest this anecdote gives anyone some Snape-style sympathy for Melkor, remember that we don’t really know why she rejected him, or even what exactly she was rejecting. Perhaps some sort of creepy romantic advances, or maybe just companionship in his quest to claim the Flame Imperishable? We’re not sure. We’re only told that “she knew him.” I see no hint of mere friend-zoning here; my guess is she’s just a good judge of character. So having been rejected, now Melkor hates her. But he also fears Varda more than anyone. This love/hate relationship he’ll have with light—perhaps owing to this unrequited romantic misadventure—is going to be a recurring stick up his ass.

Ulmo, the not-so-gregarious Lord of Waters, is up next. Aside from being the master of all things wet and watery, he’s a bit of a hermit/nomad among the Valar—making him the most independent of them all, but in a decidedly un-Melkorian way. Ulmo goes out alone, not to possess but to explore, to ruminate, to observe. Of his peers, it will become obvious that he is also the fondest of the Children of Ilúvatar. Even in the ages to come, when things look bleak for them, he is never so far away. His spirit, as the Elves will say, “runs in all the veins of the world.” Appropriately, he’ll also be the nosiest of the Valar. We also know from the Ainulindalë that he gets along well with Manwë.

Aulë is the Vala with mastery over the fabric of the Earth itself: rock, soil, and all terrestrial matter. He’s the quintessential smith and tinkerer who, like Melkor, desires to make new and original things of his own. But quite unlike that malefactor, he has no interest in possessing what he makes. He crafts things and immediately gives them away, moving on to the next project. His labors of love and impatience for the arrival of the Children will actually get him in a spot of trouble a little ways down the line. Moreover, some of his underlings—we’ll get to those later—also have a tendency to covet things a little bit too much. When matter itself is your forte, I suppose it’s easier to be materialistic.

Yavanna (ya-VON-nah), the Giver of Fruits and Queen of the Earth, is the ultimate gardener. Plants and beasts and growing things are her jam (and she probably makes actual jam, too). Her husband is Aulë, and their respective areas of expertise (stone and soil, plants and animals) make them a complementary yet occasionally contentious couple at times. And not to be too…well, hasty…but trees will hold a special place in her heart.

Mandos (MAN-doss) is a dude who’s going to come up quite a bit a few chapters from now. He’s called the Doomsman of the Valar, “keeper of the Houses of the Dead, and the summoner of the spirits of the slain.” Which…damn, that’s metal. He’s grim, he issues judgments, and he’s kind of a know-it-all, too. He’s the well-read goth of the Valar, always hanging out at the library, always saying ominous and portentous things. Everyone likes Mandos, but he’s the sort of guy you’d be nervous to have turn up on your doorstep—him or his creepy, tapestry-weaving wife, Vairë.

Lórien is Mandos’s little brother and he’s all about visions and dreams. But he’s mostly known for his especially sweet digs: the Gardens of Lórien. Galadriel will one day name her forest realm in homage to his, and according to pretty much everyone who’s ever visited the place, Lórien is the most beautiful place in all of Arda. That’s really saying something (and would likely garner some fantastic reviews on TripAdvisor).

Nienna (nee-EN-nah) is the sister of both Mandos and Lórien, and she embodies grief and sorrow. She “mourns for every wound that Arda has suffered in the marring of Melkor,” and it was in some part her sorrow in the Ainulindalë that was woven into the Music. For all that Nienna may sound like a bummer to be around, she actually exemplifies Ilúvatar’s mercy, turning woe into strength, grief into hope, and “sorrow to wisdom.” It is she who brings such boundless compassion to the world—and anyone who’s read The Lord of the Rings knows a thing or two about the importance of pity and mercy. That’s no coincidence, given the Maia who serves as Nienna’s protégé (below—keep reading!).

Oromë (OH-roh-may) is the hunter and scout of the gang. He’s also a keeper of beasts and hounds (shout-out to Huan!), and is the Vala who seems to love the physical lands of Middle-earth best. And then there’s Tulkas, the hands-on pro-wrestler of the Valar, a muscle-bound, good-humored warrior “who is of no avail as a counsellor.” I guess you could say that where Oromë is the ranger with high Wisdom, Tulkas is the barbarian who made Intelligence his dump stat so he could max out his Strength. He’s the guy who’ll laugh when you punch him in the face, and laugh harder when he gives you a mouthful of teeth. Tulkas is kind of the odd Vala out, because he’s not one of the fourteen Ainur who first volunteered to come down into the World. Rather, he comes in later merely at the promise of battle. Still, while it’s fun to assume he’s kind of dim, he simply gives no thought to the past or future. He’s a Vala of action, not words.

So that’s the Valar. There are a few more, but they don’t come up too much. Doesn’t mean they’re not important, or shaping and guiding the World in vital ways; they simply don’t enter into these tales as much. We’ll definitely see a lot of Manwë and especially Ulmo.

Now we come to the Maiar (singular, Maia), those spirits who came into the World with the Valar and who are just as old. There a whole bunch of them living among the Valar, peopling their courtyards and parks, but we’re not sure how many or who they all are. They’re of the “same order”—meaning they are Ainur, too, “but of less degree.” Which also means they also participated in the Music of the Ainur. (I imagine they didn’t handle the main riffs and certainly took no solos, but probably added color in ways like adding reverb, doing backup vocals, or playing cowbell.) Generally speaking, the Maiar are not as powerful than the Valar, but there are some exceptions to this, and the difference in might between one Maia and another can be enormous.

It’s worth noting that Maia are usually vassals of specific Valar, too. Accordingly, each has his or her related skills and proclivities. So a Maia in the service of Mandos would probably be judicious, chat with the spirits of the dead, and keep her house stark and somber; while a Maia of Yavanna might decorate his house with garland, won’t shut up about kale, and get from A to B on a rabbit-drawn sleigh. I mean, just spitballing here.

So which of the Maiar are worth remembering?

Well, Eönwë (ay-ON-way) might be, since he’s the herald and standard-bearer of Manwë. (Apparently the Valar are into banners.) We’re told that Eönwë’s “might in arms is surpassed by none in Arda,” and that’s really saying something when you consider the existence of both Oromë the ranger and Tulkas the barbarian. Come to think of it, I think this makes Eönwë the quintessential fighter in the Valar’s D&D party. He’s the kind of guy who leads the charge when it matters most, and he’ll come up a few times in future chapters when battle is afoot. Yet Eönwë isn’t warmongering in the least. He’s passive, taking up arms only when the Valar require it. A professional soldier, this guy.

Ossë (OSS-ay) is the wild Maia of roaring coastal waters, leaving the deeper oceans to his boss, Ulmo, and he delights in the storms that Manwë brings down upon the waves. Fascinatingly, we are told that Ossë was almost drawn into the service of Melkor in the shaping of Arda. Yet he atoned for it and was forgiven. So, why would Melkor choose Ossë for conversion? Well, certainly for his susceptibility; Ossë’s temperament is as wild and untamed as the crashing waves and Melkor is the sort of fellow who can inspire rebellion in others. For Ossë, the temptation was the promise of greater glory. But mainly it’s because we’re told that Melkor could never master the Sea and therefore hated it, so he sought a vassal who could tame it on his behalf.

You know, Melko sure hates a lot of things. Certain objects of his dismay get called out from time to time. So I think it’s time to see his running list, and update it periodically.

Anyway, the next Maia worth remembering is Melian, vassal of Lórien, who hangs out in his gardens. Try and remember her; she is easily one of the most important of the Maiar in this book. Once the Children of Ilúvatar enter the world stage, she’ll get involved in a very personal way, to the point that she excuses herself from the other Valar just to stay with them—and one in particular. She’s all about birdsong and nightingales. As we’ll see, if the First Age had a slogan, it could be: Why doesn’t anyone ever listen to Melian?

Then there is Gandal— Ah, I mean, Olórin. He serves Nienna, the Vala of grief and mourning, and will later impart her wisdom to many peoples in Middle-earth. Long, long before he appears to Elves and Men, Olórin simply hangs out, unseen, watching them. This is a chap who puts in the time, cuts no corners, and really does his homework when it comes to learning the hearts of the Elves and of Men. “I will not say: do not weep,” he will tell some very sad hobbits someday, “for not all tears are an evil.” We’ll see him again, but not until the very end of The Silmarillion, when all that watching and learning pays off. What’s he doing through all the turmoil between then and now? I wish we knew.

But not all Maiar are on the Nice List. Some throw in with Melkor, as Ossë almost did. Melkor must be as charismatic as he is nasty, given how many seem to come under his influence. Jealous and arrogant from nearly the start of everything, Melkor had coveted Ilúvatar’s Flame Imperishable, and that desire has twisted him into something especially vile. And unrepentant. He has become “a liar without shame,” using his talents to pervert others to this will:

For of the Maiar many were drawn to his splendour in the days of his greatness, and remained in that allegiance down into his darkness; and others he corrupted afterwards to his service with lies and treacherous gifts.

We don’t know how many Maiar fall into his service—this book is scarce on exact numbers—but clearly they’re enough to give Melkor some serious muscle. Especially the Balrogs, who were formerly just spirits of fire hanging out in the Timeless Halls but who have now become “demons of terror” after collusion with Melkor. That’s right: the Balrog who would later become known as Durin’s Bane—who would menace the Fellowship, and who would scuffle with Olórin high in the Misty Mountains—once took part in the Music of creation itself. Indeed, possibly right alongside Olórin himself. It had even once looked upon Ilúvatar himself and beheld the vision of Eä. It’s quite a fall. Melkor is such an asshole for bringing down so many once-splendorous beings.

And speaking of assholes, lastly we’re introduced to Melkor’s right-hand man and the mightiest of the Maiar in his camp: good ol’ Sauron, who started off as a vassal of Aulë and was therefore a master of arts and crafts long before switching sides. Cunning and skilled with his hands, Sauron was probably voted Most Likely to Forge A Super Powerful Ring in his graduating class. For now, he is merely the lieutenant of Melkor.

Although not specifically called out in The Silmarillion, there is one other bad Maiar apple who will eventually fall from Aulë’s tree of artifice…but not until many ages have passed. Poor Aulë must have had some uncomfortable discussions with HR. (And HR is probably his wife.)

“Spoiler” Alert: The Valaquenta drops a few solid spoilers. One of which is that Melkor will be given a new name at some point and earn the epithet the Dark Enemy of the World—which, geez, go big or go home, right? We’re also told that although he had started out as the most powerful of the Ainur, he “squandered his strength in violence and tyranny.” And bit by bit, we will see how. The craziest spoiler is literally in the last sentence, a place in his prose where Tolkien often likes to be especially dramatic. We’re given a heads up that Sauron, like his master, will walk “the same ruinous path down into the Void” See, just a few pages in, Tolkien is ruining the end of The Lord of the Rings. So inconsiderate!

“Of the Beginning of Days”

Remember those huge swaths of unmeasured time I mentioned in the Primer intro? The first few chapters of The Silmarillion are rife with ’em. In these early days, while Melkor wages war against the Valar and their works in ways we can only imagine, there is no sun in the sky yet for measuring years. There aren’t even seasons yet. The epochs that pass are poetically named, not numbered.

You’ll notice the narrative is not seamless between the Valaquenta and this first chapter in the Quenta. For example, although we’ve been given a helpful profile of the major players, they’re not actually dwelling in the homesteads with which they’re associated. Not yet. They’re still Arda-sculpting here at the start. But despite Melkor’s constant subversion—as mentioned at the end of the Ainulindalë—the Valar have at least gradually gained the upper hand, and the world is more or less in a solid shape. It’s wondrous but still very different from the Arda the Elves will come to know when they show up.

The action really begins with Tulkas the Strong, who hears there’s some sort of brawl going on down in the “Little Kingdom” and totally wants in on that. So he leaves the Timeless Halls and drops down into Arda, eager to bust some heads. Namely, Melkor’s. Yes, Melkor is still a powerful being. But when the universe’s answer to the Kool-Aid Man comes bursting onto the scene, laughing the whole time, Melkor wisely retreats—presumably shaking his fist like Skeletor at He-Man and assuring everyone that he’ll be back.

And he sure will. Melkor doesn’t just going into hiding, not with Tulkas looking for a fight. He leaves Arda altogether and goes out to some dark corner of Eä to brood. Seething with hate for Tulkas especially. So you know what? Tulkas is going to have to go on that hate list.

Then a long time passes and all is quiet. The Valar get back to work, this time in peace, preparing the Earth for the coming of the Children of Ilúvatar. Which is what they signed up for, after all. They still don’t know where or when these Elves and Men will show up, so they just busy themselves with preparations. Tulkas sticks around because he likes what the others have done with the place—and hey, is that Oromë’s sister he sees over there? She’s quite a looker.

Meanwhile, preeminent botanist Yavanna starts planting the seeds that she’s been dreaming up since forever ago in the Timeless Halls, where she’d probably tacked crayon drawings of trees and flowers all over Ilúvatar’s refrigerator. But one thing is still missing: sufficient light.

And that’s something easy to overlook. Arda is still rather dark in this primeval age. Sure, Varda’s stars are wheeling overhead beyond the exosphere, and who knows what kind of wondrous auroras or other light-emitting phenomena were thought up in the Music of the Ainur? But by and large, the world is still quite dim by our standards. There’s no sun; there’s not even a moon. And this has all been fine thus far because there are no Men lumbering about in need of light yet. But most of Yavanna’s plants seem to have been devised with photosynthesis in mind. And sure, eventually the Children of Ilúvatar are bound to show up, and they’re going to need to walk around without bumping into each other, too.

Thus at the request of Yavanna, the industrious Valar get to work, doing what they do best: teaming up, being harmonious, getting shit done. Many Valar hands make light work!

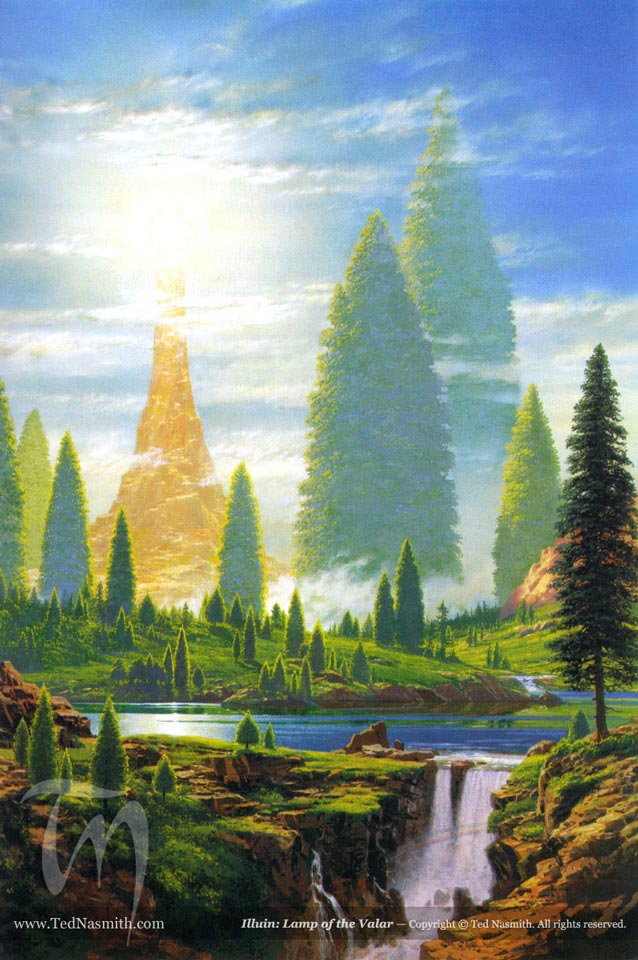

So with Melkor still out of the picture, they undertake an impressive feat of engineering—probably with the help of numerous Maiar contractors. The result is the construction of two colossal, pillar-like Lamps that become the primary source of Arda’s light. Aulë and his team handle primary manufacturing, Varda does the lighting, Manwë does the hallowing. And I assume Tulkas does a lot of the actual heavy-lifting—probably laughing the whole time, the weirdo. The two Lamps are then raised up on opposite sides of the world. The northern one is blueish in hue—one might be tempted to say moonlike—while the southern Lamp’s light is yellowish. The Earth is thereby filled with light “as it were in a changeless day.” The Lamps are the ultimate utility—there is no nighttime now, just ceaseless, life-giving light.

This begins what is called the Spring of Arda, and the world is as close to perfect as it can be. By the light of the Lamps, green and growing things sprout up and explode with life. Trees “like living mountains” arise and animals pop up to inhabit the fertile lands of Middle-earth. Yavanna has to be giddy; this is her time.

The Valar take up residence together in a place called Almaren, an island in a huge lake at the center of Middle-earth. In this region, the light of both lamps overlap splendidly, and since all Valar are gathered together (though I’m betting Ulmo still comes and goes), it’s an especially marvelous place to be. After all that Lamp-building, the Valar finally take a break. They party. They’re happy. They even hold a wedding for Tulkas and his bride, Nessa (the aforementioned sister of Oromë!). Nessa is into running and dancing, and does performance art for everyone on lush green Lamp-lit lawns.

These are the celebratory salad days of Arda, and they last for an indeterminately long time.

But this festive atmosphere and the markedly lax vigilance of the Valar allows evil to creep back into the world. Melkor, remember, had left Arda completely. In these early days, he hasn’t squandered his power yet, and he can still do things like this—can come and go as a formless spirit—as long as the Valar don’t actively hinder him. And with Tulkas and the others resting, they don’t.

It’s not necessarily that the Valar or their Maiar subjects are simply falling asleep at their posts, either. They’re naïve; they’re not watchful against Melkor. As wise as they are, the Ainur as a whole have a long way to go in understanding even each other—we’re told that from the start—much less the deviant mind of Melkor. And even Manwë can barely comprehend that his brother would do the harm that he does. It’s not that the Valar can’t quantify evil, it’s that they don’t really fathom its existence. Yet. Even when Melkor was spoiling their efforts early on, they simply persisted—like ants rebuilding a knocked-over anthill. They didn’t retaliate and attack him directly. (Only Tulkas was going to do that when he first showed up, because that’s what Tulkas does.) How does one prosecute when crime isn’t even a thing yet?

The timing of Melkor’s return isn’t coincidental. He’s had informants all along in Almaren, spies already in his service. And now, drawing near again, he looks down on the Spring of Arda and at what the Valar have made, and he hates and envies it all the more for its splendor. Arda should have been his to rule—those jerks just didn’t listen to reason—and now it’s a vibrant green world under these garish and ridiculously oversized lamps. On the list it goes! That list is getting long.

That list is getting long.

All that light, man! Light which should have been his alone to command. Light that Ilúvatar had given forth, light captured in Varda’s own lovely face, and now light she’d gathered up and displayed for all to enjoy. Well, if Melkor can’t control the supply, then no one should!

Together with “spirits out of the halls of Eä that he had perverted to his service,” Melkor slips over the Walls of Night—essentially the boundaries of Arda. Hidden by the great shadow of the northern Lamp, he reenters the world, and down he delves into the earth. There in the far north he creates a hidden fortress, Utumno, where he sets up shop for all the horrors he’s got planned. His malice and ill will flows out of him like a blight.

When the Valar start to notice things in the natural world growing sick, beasts turning to monsters, “rank and poisonous” fens appearing, and forests growing dark, then they know that Melkor is back. Back in business. Screwing things up. But it’s kind of too late now.

Melkor with his dark host reignites war with the Valar, culminating in the toppling of the Lamps themselves. We don’t know how he manages this. With an intricate pulley system? A team of synchronized Balrogs with massive chains or rams? Did he have some of his Maiar spies, while feigning service to Aulë, deliberately introduce a design flaw into the Lamps’ construction? Something that, when the moment was right, Melkor could exploit? We don’t know! But he pulls it off and down come the Lamps!

And this cataclysm changes everything. So titanic are these Lamps and the energies that power them that when they fall, the very continent of Middle-earth is split apart; “destroying flame” spills out across the lands—burning, devouring, tearing things up.

And the shape of Arda and the symmetry of its waters and its lands was marred in that time, so that the first designs of the Valar were never after restored.

The island of Almaren is totally obliterated, and the Encircling Sea flows in where the land breaks apart. So now we’ve got some big continents formed from the whole: Middle-earth is now the name given only for that primary eastern half, while Aman is the name given to the western continent; henceforth there is a clear distinction between these two. And Aman is where the Valar regroup after this great turmoil and destruction.

Melkor wisely pulls back at this point, since Manwë and Tulkas are especially pissed off and actively go looking for him. He hides out in Utumno and they do not find him. Moreover, the Valar all have their hands full trying to quell the destruction, put out the fires, and salvage what they can. Yet they also try to minimize their land-shaping and fissure-closing tricks, or whatever it is they can do, because they know all too well that the Children of Ilúvatar could show up at any time and they’re going to be fragile little things by comparison. They dare not risk harming them.

Once they’ve done what they can, the Valar regroup in the West, to Aman. And this time they fortify against Melkor, literally raising up mountains on Aman as a barricade against his aggression. The breaking of the Lamps really spooked them.

In describing the new settlements, Tolkien throws down a bunch more names and titles—in some ways he’s reintroducing the most notable of the Valar. It’s elegant language to read but difficult to keep track of. You needn’t worry about most of the names on a first read-through. What matters is that the Valar are shoring up their defenses in Valinor, a region of Aman, and that they’re leaving Middle-earth alone for now. This is when each of them establishes their estates and gardens, as mentioned in the Valaquenta above. For example, it’s at this time that Manwë and Varda set up their home in a tower on Arda’s tallest mountain, Taniquetil (tah-NEE-kwuh-teel), gaining an impressive vantage on the World.

You can think of Valinor as a place of pure concentrated Ainur power. It’s a fortress, watchtower, and sprawling palace all in one. And because they’ve had to give up trying to make the entire world perfect, the Valar are at least able to make one region especially awesome:

In that guarded land the Valar gathered great store of light and all the fairest things that were saved from the ruin; and many others yet fairer they made anew, and Valinor became more beautiful even than Middle-earth in the Spring of Arda.

A city, Valmar, is built, and just beyond its western gate, on a giant green hill, a new project eventually gets underway. If the Lamps of the Valar were the original world premier blockbuster, then this is the smaller-release (but miraculously better) sequel. Yavanna’s powers of growth and Nienna’s tears of mourning mix together in the soil, and from that fertile mound grow the Two Trees of Valinor. High of stature, each produces mind-blowingly beautiful light from its very leaves, one with white and silver light and the other with golden hues. Even their dew is like liquid light, and Varda collects it in lake-sized vats for storing.

The light of the Trees even wax and wane in regular phases, which has the effect of making time measurable. No one had been keeping track before; but now begins the Count of Time. And this first epoch is called the Bliss of Valinor; it will be referenced quite a few times in chapters to come.

“Spoiler” Alert: Amidst the talk of these new lights, Tolkien refers to “all the joyful days until the Darkening of Valinor,” which casually reminds us that with evil still afoot somewhere, the Valar can’t have nice things forever. He doesn’t clarify at this time, but we know already that the days of bliss are indeed numbered.

Still, while they do last, these Two Trees are a huge deal, and whether one has looked upon their hallowed light, or not, will make all the difference to the Elves someday. Granted, those giant Lamps had once lit all of Arda. The Trees light only Valinor properly—the difference between a bold room-illuminating halogen lamp and an unspeakably lovely night light in one well-furnished corner.

But this means that across the Great Sea that now lies between them, Middle-earth itself remains shrouded in gloom, lit only by the stars. And now Middle-earth is stalked by Melkor, who seems to have free rein there for the moment.

Well, not quite. A couple of the Valar are unwilling to leave Middle-earth completely to Melkor’s machinations. First, Yavanna—sweet, hippie Yavanna who just wanted things to flower and grow—actually urges the other Valar to wage war against Melkor directly for what he’s done and may still do again. At first glance, she seems like she’d be the most passive. She’s the creative force behind the Two Trees, and those are forever remembered as her greatest work, but she doesn’t just cultivate things and sit around. Like her husband, she makes things and moves on to other works. And when you really pay attention you’ll see that Yavanna is no shrinking violet; she’s a freaking Mithril Magnolia.

Second, Oromë the Hunter also returns often to Middle-earth’s dark forests with his steed, his bow, and his spear, all too eager to hunt down Melkor’s monsters. He’s unwilling to let them go unchecked. Two chapters from now, Oromë’s wanderings will pay off, too.

And so because the Valar’s high-level ranger and druid keep intruding on his turf, Melkor is forced to keep a low profile. He can roam farther afield than he could in the days of the Lamps but he knows he still has to stay under Manwë’s radar. Still, his bold return has put the Valar on the defensive. So much so that it’s given him a shadowy playground—Middle-earth—where he can at least play the bogeyman, if not a great king.

But beyond this stalemate, mostly we’re seeing the Valar sit and wait and watch for the coming of the Children of Ilúvatar.

“Spoiler” Alert: During the descriptive end portion of this chapter, we’re told a couple of times that Aulë will be associated with a particular group of Elves when they come—the Noldor, they’re called, and they’ll be big fans and pupils of his. Never mind that name for now, but out of this mention comes a one-sentence synopsis for the entire Quenta Silmarillion:

The Noldor also it was who first achieved the making of gems; and the fairest of all gems were the Silmarils, and they are lost.

So, uhh, when we do get to see the titular Silmarils, don’t get too attached. Not like…some.

Finally, the chapter ends on a fascinating philosophical note. At some point, long after the Valar have retreated and settled into Valinor, Ilúvatar speaks to them again—and it’s one of the last times we’ll hear from him directly throughout The Silmarillion. Which is deliberate. He’s largely a hands-off creator, having entrusted the World to the Valar, involving himself directly only for very big, crucial reasons. Anyway, he points out to them that of the two kindreds of the Children of Ilúvatar, Elves will “bring forth more beauty” than Men and have “greater bliss” in the world. This will translate into the grace and joy and comeliness that Elves will enjoy; it is what makes us Men see them as fair and wonderful beings. But to Men, Ilúvatar says he will give “a new gift.”

The gift he speaks of is a curious thing. For one, it is a type of freedom that’s difficult to grasp—not just for we the readers, but for the characters. Men, Ilúvatar says, will “stray often,” and make poor choices, and to the Elves they will seem like little Melkors—going wrong far more often than themselves. But if the Ainur and the Elves have free will (and they do, kinda sorta, in a different sort of way), Men seem to have an especially free will. They are not bound to the World in the same way:

Therefore he willed that the hearts of Men should seek beyond the world and should find no rest therein; but they should have a virtue to shape their life, amid the powers and chances of the world, beyond the Music of the Ainur, which is as fate to all things else; and of their operation everything should be, in form and deed, completed, and the world fulfilled unto the last and smallest.

Beyond the Music?! That’s no small thing. The Music is all the Ainur have known, along with the attempt to realize the vision that it created.

And this gift to Men is also the gift of death. Elves will not have death, not as such. Elves will be immortal, and live in spirit and in body as long as Arda itself does—however many ages pass. Even if they are slain in violence, Elves will go to the Halls of Mandos and might be rehoused in body again, and live on, be it on Middle-earth or in Valinor, but still within Arda.

But not us! Men will “dwell only a short space in the world alive, and are not bound to it, and depart soon whither the Elves know not.” So for all the grief that may come to Men by the cruelties of Melkor—and we’re told up front that he’ll hate and fear Men, too—we will only be subject to it for a short time, then be ushered along to an unknown future beyond Eä that only Ilúvatar knows about. Not even the Valar get to know.

Hence we are called the Guests of Middle-earth, the Strangers. In the next installment, we’ll listen in on a fun but profound little marital squabble called “Of Aulë and Yavanna.”

In the next installment, we’ll listen in on a fun but profound little marital squabble called “Of Aulë and Yavanna.”

Top image: “Manwë” Dymond Starr

Jeff LaSala can’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone. He also wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, some cyberpunk stories, and some RPG books. And now works for Tor Books.