In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

There is nothing quite like reading about the act of exploration: tales of expeditions up mysterious jungle rivers, archaeologists in lost cities, spelunkers in caverns deep beneath the earth, or scientists pursuing the latest discovery. And in science fiction, there is a special type of story that evokes a particular sense of wonder, the Big Dumb Object, or BDO, story. A giant artifact is found, with no one around to explain it, and our heroes must puzzle out its origin and its purpose. And one of the best of these tales is Larry Niven’s groundbreaking novel, Ringworld.

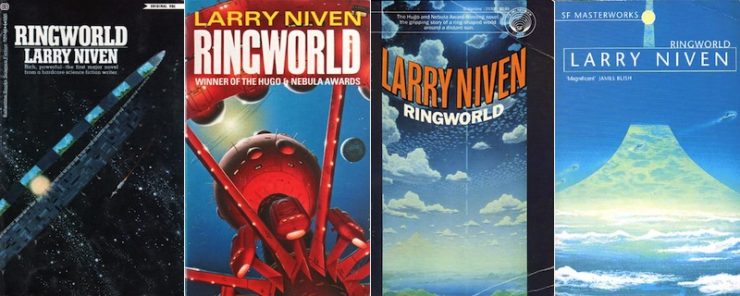

I first discovered Ringworld when I was in high school. I can’t remember where I found it, probably at the local independent department store (which filled the same ecological niche the local Walmart or Target does now). In those days, paperbacks were everywhere, with books and magazines occupying a far larger area in stores than they do today. I recognized Niven’s name (I suspect from an appearance in either Galaxy or Analog, both of which my father subscribed to), and the premise sounded intriguing, so I plunked down a buck and a quarter and brought it home. The fact that the paperback was in its fourth printing in the two years since it had first appeared was also the kind of thing I would have noted, in deciding how to spend my hard-earned dollars.

The term Big Dumb Object (BDO) is said to have originated with British writer Roz Kaveney, and was popularized by Peter Nichols in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. It usually involves some massive object or megastructure, like a giant spaceship appearing from the unknown, or explorers discovering a construct like a Dyson Sphere. Another noted BDO novel, which appeared shortly after Ringworld, was Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama.

About the Author

Larry Niven, born in Los Angeles in 1938, is one of the planet’s most widely known and successful science fiction authors. His work has garnered a host of awards from a variety of organizations—including five Hugo Awards, with short story awards for “Neutron Star,” “Inconstant Moon,” “The Hole Man,” and “The Borderland of Sol,” and the novel award for Ringworld (which won the Nebula Award and Locus Award, as well). In 2015, SFWA recognized Niven for his lifetime achievement with the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award.

He is particularly known for writing stories that hinge on recent scientific discoveries or new theories. As a creator of intriguing alien races, Niven is a clear heir to Stanley G. Weinbaum, whose work I reviewed in my last column. He has frequently been involved in collaborations, with the most notable of these being his long and productive relationship with Jerry Pournelle, which produced best-selling books like Lucifer’s Hammer, The Mote in God’s Eye, and Footfall. Other collaborators have included Steve Barnes, Gregory Benford, Brenda Cooper, and Edward Lerner.

I did get the chance to meet Mr. Niven once at a convention, in a huckster room. Unfortunately, I asked him to autograph a book—and discovered that people asking him for autographs outside of scheduled events was one of his pet peeves. So, if you ever meet him at a convention, learn from my mistake, and don’t be that guy who blows a chance to get off on the right foot with one of their favorite authors.

The Universe of Known Space

Even a quick search of the internet shows that Larry Niven’s Known Space, and the Ringworld in particular, has captured the imagination of many readers. You see it in the collection of images that appear, and in the number of websites that discuss the author and his works. Known Space is one of the most compelling of what the SF world calls “future histories,” a whole body of work knitted together in a single consistent setting and timeline. And the sheer scope and exuberance of Niven’s vision shines through even the simplest facets of this universe. In researching for this article, however, I found an even better source than the internet on my own bookshelves: The Guide to Larry Niven’s Ringworld by Kevin Stein, published by Baen Books back in 1994.

Even a quick search of the internet shows that Larry Niven’s Known Space, and the Ringworld in particular, has captured the imagination of many readers. You see it in the collection of images that appear, and in the number of websites that discuss the author and his works. Known Space is one of the most compelling of what the SF world calls “future histories,” a whole body of work knitted together in a single consistent setting and timeline. And the sheer scope and exuberance of Niven’s vision shines through even the simplest facets of this universe. In researching for this article, however, I found an even better source than the internet on my own bookshelves: The Guide to Larry Niven’s Ringworld by Kevin Stein, published by Baen Books back in 1994.

Niven’s work is rooted in the real universe, reflecting the most up-to-date knowledge and science at the time he was writing. His stars are real stars, and the physical laws are also consistent with the current field of physics and astronomy. But he is also not afraid to go beyond modern physics, and speculate about things we may not have discovered yet. One of these elements is faster-than-light travel, something that is essential to a future history whose denizens go gallivanting around the galaxy. Another is the control of gravity, both within a vessel and to propel it, using gravitational force to power a flying vehicle or personal lift belt. And yet another element is teleportation, which is possible between booths at short ranges (point to point on a planet), an innovation that has effectively homogenized the societies of Earth. Stasis fields can also immobilize everything within them in suspended animation. And there are extra-sensory powers, which include forms of telepathy, minor telekinesis, and even enhanced luck.

Among the older alien races in Known Space were the Thrint, or Slavers, who billions of years ago enslaved other races with their telepathic powers. A revolt by the Tnuctipin and Bandersnatchi exterminated the Slavers, but not before the Slavers destroyed nearly every other sentient race in the galaxy in retaliation, leaving artifacts and technological wonders from that era scattered around the galaxy. Other races include the Outsiders, helium-based life forms who spend most of their time in deep space, and trade among the stars. The Pak are an ancestor of humans who have two phases of their lives: a breeder phase, and a Protector phase where they gain greater strength and intelligence when exposed to a virus that lives in Tree-of-Life fruit. Humanity evolved from breeders who were never exposed to the Tree-of-Life virus because it could not survive on Earth. Puppeteers are a highly evolved race of individually timid three-legged herbivores, with brains in their torsos, and an eye and a mouth with prehensile lips on each of their two arms. The Kzin are a race of giant, warlike felines who have clashed with humanity several times. Only a visit by Outsiders, who sold human colonists a hyperdrive, allowed the humans to survive the first of those conflicts. Dolphins of Earth were found to be intelligent when telepathy-enhancing devices were developed. Other races that humans have encountered include Grogs, Kdatlyno, and Trinocs.

The planets colonized by humans reflect the wide range of Niven’s imagination. They include Plateau, a planet where only a mountainous area the size of California rises above the otherwise toxic atmosphere of the planet. We Made It is a planet frequently scoured with supersonic winds that have driven the colonists beneath the surface of the land masses and the oceans. Home is an Earth-like planet whose population was later converted to Protectors by the introduction of the Tree-of-Life virus. Jinx is a highly advanced colony on a moon that orbits a gas giant, where humanity encountered the Bandersnatchi, and after discovering they were intelligent, learned about the ancient Slaver rebellion. Wunderland is an Earth-like world colonized by an aristocratic population that was conquered during one of the Man-Kzin Wars.

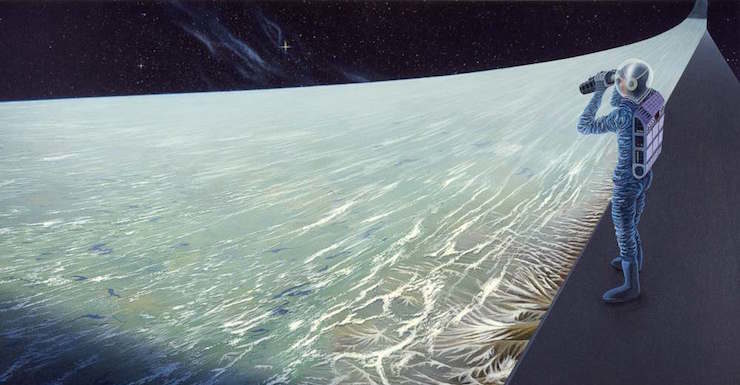

And, of course, there is the Ringworld: a mysterious ribbon of super-strong material that encircles a star, spins at a rate that creates an Earth-like gravity, has walls that capture an Earth-like atmosphere, and contains its own oceans and weather systems. The construct has the surface area of thousands of worlds, and the features of many of the worlds in Known Space are replicated on its surface. Day and night are created by a ring of shadow squares that orbit closer to the star, and spin at a different rate than the Ringworld itself. When it was first discovered by Puppeteers, no one knew who had created the Ringworld, but all realized its creators must have been a race with an unimaginable level of technology and industry.

Ringworld

I confess that, right from the start, I got off on the wrong foot with the book’s protagonist, Louis Wu. For some unfathomable reason, he has chosen for his 200th birthday party a hairstyle, makeup, and clothing that to me felt rooted in a negative Asian stereotype. Louis is also suffering from what we now call “First World problems”: too much wealth, too much comfort, and not enough challenges. Boredom and restlessness drive Louis to leave his party, and he uses teleportation booths to hop around the world, only to have a Puppeteer named Nessus hack into the teleportation network and bring him to an anonymous hotel room. Louis is intrigued, knowing that the Puppeteers fled Known Space upon the discovery of a massive explosion radiating out from the galactic center at light speed, and due to impact human worlds in about 20,000 years. When Nessus offers Louis a chance to explore a strange solar system in return for giving humanity a better hyperdrive, he sees it as a way to escape his own ennui. Nessus, as are most Puppeteers who interact with other species, is a manic-depressive that other Puppeteers consider mentally ill; while his actions are sometimes less than admirable, he is to me a far more interesting character than Louis.

The pair then look for two others to round out their crew. The first is a Kzin called Speaker-to-Animals, a youngster looking to make a name for himself as a warrior; like all his kind, he is a barely-contained bundle of aggression. He is also my favorite of all the characters in this tale, with an earnest devotion to duty and dignity. One of the best lines in the book comes in response to someone calling Speaker-to-Animals “cute.” “I do not mean to give offense,” he replies, “but do not ever say that again. Ever.” Louis, the Puppeteer, and Kzin then return to Louis’ birthday party, only to find the fourth person that Nessus had been searching for right there at the party. She is Teela Brown, a product of many generations who won the right to reproduce in birthright lotteries. The Puppeteers feel this has bred humans who actually bend the laws of probability. Louis scoffs at this idea, but Teela is a pleasant bundle of optimism, and has apparently never suffered serious pain or setbacks in her life. Louis and Teela start a physical relationship, but he condescends to her repeatedly, another mark against him.

The four of them leave in the “Long Shot,” the superfast hyperdrive ship that, in the hands of explorer Beowulf Schaeffer, discovered the explosion of stars at the galaxy’s core. Their destination is the home world of the Puppeteers, long a mystery to other races. I will not go into detail about what they find, because the wonders they see are one of the many fascinating things revealed in the novel. They find their ship, a supposedly peaceful vessel full of equipment that can be repurposed as weapons, which the crew names the “Lying Bastard.” Built to Puppeteer standards, the ship has an automatic stasis field that protects everything in the hull during an emergency, and has most of its drives and other equipment mounted on its wings. Approaching the Ringworld, they examine its basic construction and layout and encounter complete silence; it appears that no one is home.

And then, suddenly, they are in stasis. When it ends, they find they have crashed on the Ringworld with the equipment on their wings destroyed, victims of what appears to be an automated meteor defense. The hyperdrive has survived, but they have no way to get off the Ringworld so they can engage it. They are trapped on a strange world, whose mysteries they must uncover if they ever wish to get home. They decide to head for what appear to be starship docks on the rim walls, and the immense size of the Ringworld proves to be a challenge, even though they are equipped with very speedy and capable flycycles. They do find inhabitants, survivors of a fallen civilization, but discover little to solve the mysteries of the Ringworld. At one point, the four are captured, and there is a diversion I found a bit creepy in which characters attempt to control each other with devices that stimulate the pleasure centers of the brain, and with sex. But this is a short interlude in an otherwise excellent tale, which barely allows us to absorb news of one marvel before presenting us with another.

And, because mysteries and wonder are such a big part of this book, and thus spoilers are even more spoilery than usual, I will leave the synopsis here.

Final Thoughts

The original Ringworld novel is one of the most enjoyable and influential science fiction books ever written. The book is like those little Russian nesting dolls, with each mystery unfolding only to reveal another. When folks assemble SF top ten lists, this book is often among those selected—SF fans crave a certain sense of wonder in their reading, and this book delivers that by the truckload.

There were three sequels to Ringworld: Ringworld Engineers, The Ringworld Throne, and Ringworld’s Children. While the books were enjoyable, some of the wonder and mystery of the original Big Dumb Object story was lost as the secrets of the Ringworld, its origin, and its operation were revealed. The Ringworld itself remains as one of the most inventive and intriguing concepts in the history of science fiction. The novel is the pivotal work in Niven’s long and varied career, immediately vaulting him into the top tier of the genre’s most celebrated authors.

And now it’s your turn to chime in. What are your thoughts on Ringworld, or the many other tales of Known Space? And what are your favorite aspects of Niven’s work?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

Great to see a Ringworld discussion starting up. Here’s a link to the Ringworld 40th Anniversary series of posts from 2010 https://www.tor.com/series/ringworld-40th-anniversary/

Ringworld is one of those “classic” books – like Foundation – which I don’t think has aged very well, at all, and its position as a classic is more down to it having a really cool idea which made people go, “That’s a cool idea!” regardless of execution. Niven’s prose is unremarkable, the book has clunking cameos from other Known Space characters (which since the novel is marketed as a stand-alone or, more recently, Book 1 of a series, is jarring) and, more entertainingly, the Ringworld does not work as a concept or an idea. Engineers noted that the thing would fall out of a stable orbit within just a few centuries of being built so Niven retconned the existence of gigantic rocket thrusters the size of Jupiter to keep the thing stable. It got very silly, very quickly, and Niven’s political views soon became intrusive to the story (his notion of the Ringworld’s massive real estate allowing for Libertarianism on a grand scale).

Ringworld is more important as an inspiration and provocation for much better extrapolations of the same idea: Iain Banks was inspired to build much smaller and more sound (from an engineering perspective) versions in the form of Culture Orbitals for his novels, which in turn inspired the Halos of the Microsoft video games, both are both stronger explorations of the same idea. Most notably, those structures are small enough to give us that vertigo-inducing view of the landscape reaching up and wrapping around far overhead; the Ringworld wouldn’t because the curvature would be so slight on the local scale that the rest of the ring would be barely visible in the distance.

The Ringworld school of BDOs also inspired Terry Pratchett’s exploration of an artificial flat planet in Strata which he then rewrote as a fantasy novel called The Colour of Magic. So Larry Niven inadvertently gave us Discworld as well. I think these inspirational achievements are more important than the book itself, which gave us only three increasingly weak sequels.

Ringworld was the first Niven I read: though I enjoyed it, having read more of his books I came to think that the strengths of his idea-oriented approach are better displayed in his short stories (as found in books such as the Known Space collection Neutron Star) than in his novels (“The Ringworld is unstable! The Ringworld is unstable!”). Known Space is a fun setting, though one with quite a few story-breaking components; the Paks, Teela Brown, etc.

Heading off-topic (but no more so than usual) I have listened to the Dirk Maggs radio adaptation of Anansi Boys and since moved on to his Good Omens series: all episodes rate highly for entertainment value and quality of execution thus far.

I very much enjoyed Ringworld & the rest of the Known Space books back in the 1980s; these days I expect I’d still enjoy them but would find them awfully dated, both socially and scientifically.

As far as the Ringworld books in particular, I did like Ringworld and Ringworld Engineers, but was increasingly unimpressed with the subsequent books — mostly because Niven kept trying to retcon more up-to-date science & technology into the later books (nanotech!) and it was just jarring — not a very good fit into the universe he had constructed beginning in the 1960s.

I’m still in love with the Ringworld itself, though. Plus all of the other megastructures he described in an essay called “Bigger Than Worlds”, which I found in his collection Playgrounds of the Mind.

I thoroughly enjoyed Ringworld the first time I read it. And have enjoyed it a couple of times since, leaving several years between reads. I am sure to return to it in the future. As for the engineering, I suspend disbelief, I simply enjoy the book as a story. An entertaining one at that. The sequels were not up to the standard of the original and I have only bothered reading them once. Note to self, when you have finished reading your current book look up Ringworld!!

I think the ultimate result is that Niven’s Ringworld is itself, a crude, poorly done, version of what has nonetheless become a classic. But this is not because Niven himself is a terrible writer, but simply because he was working with it at more or less the beginning, so obviously it’s more of a proto-type than the results we see today.

Still, he gets things wrong, some worse than others (Oath of Fealty being a bigger example), and even accidentally reversed the rotation of the Earth(fixed in reprintings). But yeah, the bit about the instability of the ring did need correction.

And to his credit, he managed to shoe-horn in the fixes with relatively few problems, as well as coalescence many of his various works into a whole, even if they weren’t intended to be. Not all, obviously, but that’s not a bad thing.

I suspect authors like Sanderson, Reynolds, and Banks owe more than many may first think to his example.

His politics can get a little grating, though not as much as some. He’s not entirely obnoxious.

Early Larry Niven is a fantastic author, with a rich imagination and a fantastic ability to turn a single idea into a fascinating story. Ringworld is of course the pinnacle of this, but the society of Gil the Arm and the evolution of Brennan and the Protectors are equally good. Not to mention the tide of Neutron Star and the horror of Bordered in Black. Dream Park is also a wonderful exploration of virtual reality integration well in advance of it becoming viable.

But late Larry Niven is a classic of when good authors go bad – his writing becomes increasingly didactic and his stories got steadily weaker. The sheer gulf between The Legacy of Heorot and Beowulf’s Children is enormous, and they are but a few years apart. .

I’d say whatever went wrong happened around 1990, because Legacy of Heorot is probably his last good book, and Fallen Angels is probably the first of the bad ones. Achilles Choice is one I do like despite the flaws – it is a half decent book that could have been great but he fumbled the landing.

Yeah, the sex in Ringworld can get weird. And it hasn’t aged well otherwise. A good read, but almost impossible to suspend my disbelief. Protector seems to have aged better, possibly because the science is so wrong that you have to ignore it immediately. His short stories are much better.

I can’t think of anything he’s written by himself since the 80’s that’s worth any effort, and his collaborations with Pournelle haven’t aged all that well either. Although” The Mote in God’s Eye” and its sequel are still pretty good.

I haven’t read it since the seventies or eighties, but I remember feeling dissatisfied at the end, though at this remove I have no idea why. I do know that while I did read other Niven, none of it has really stayed with me at all the way some other authors I read at the time have.

Loved Ringworld since I first read it in high school (but in the mid-90s), and I enjoy a lot of Niven’s work. Thanks for this article, Alan.

@1 Thanks for the link to that previous series, which is from a time before I started regularly visiting Tor.com. Lots of good stuff there!

@3 I agree with you that Niven’s idea-oriented stories work better in short format. Because of that, I thought about reviewing the Tales of Known Space anthology, or the later Crashlander anthology. But Ringworld is so pivotal to his Known Space series that I decided to stick with that. And his retconning tendencies were really on display in Crashlander. The framing material was full of re-explaining what had happened in the original stories based on subsequent scientific discoveries, not to mention setting up Beowulf Schaeffer as Louis Wu’s step-dad, which makes going back to Ringworld very jarring, when none of the characters, including Louis, seem to know that fact.

This was a beautiful novel that I didn’t read until my mid 30s. I don’t know how it never came across my desk nor how I really came into possession of it, but the sense of wonder and excitement was fantastic. Yes, you could tell the science wasn’t up to date and yes, the way the story works with the alien races in the beginning is rough but it’s still original and I’m sure sparked the imaginations and careers of many other writers and table-top gamers. I highly suggest it as a read to anyone wanting to read a life changing book (It was for me – there is before Ringworld and after), much like The Lord of the Rings. However, I haven’t ever touched the sequels, mostly out of fear that they’d ruin the original.

I can only re-read Niven with the same kind of mind-set I apply to Victorian novels: “This is an historical artifact, and reflects the attitudes of the author’s social class (straight white male) and era.” That’s for the “classic” Niven, of course; the later stuff starts at “unreadable” and goes downhill from there. But I do sometimes re-read the early stuff, and it’s an interesting reminder of both the limitations and the expansive vision of that era.

I have met Niven at a convention only once. He was drunk and obnoxious and had clear ideas of his centrality in the universe. I didn’t ask for an autograph, or in fact do anything except make sure I stayed well out of reach.

I enjoy Ringworld and don’t see Louis as being a bad Asian charicature. Heck teenage me was thrilled that not only was he the protagonist but that he got the girl (well, *a* girl [well, kind of a girl in a manner of speaking])! Looking back as an adult, I can see how the tasp could be uncomfortably similar to opium for some people, but it doesn’t bother me.

@14 I didn’t say Louis was bad Asian caricature. I said he chose to dress in that manner at his birthday party, a choice that grated on me right from the moment the author introduced him. Other than that, he seemed pretty generic to me, which fits into Niven’s premise that teleportation booths had homogenized the various cultures of Earth.

Not just homogenized, but homogenized into a kind of specific 60s/70s southern California culture.

16: With a light garnishment of the en-vogue speculation of the future evolution of it.

I can’t remember just when I first read Ringworld – sometime in my late teens. I enjoyed it hugely, and also enjoyed the sequel, Ringworld Engineers, read in my early twenties. Though Ringworld Engineers did wrap up some of the readily apparent issues with Ringworld itself, the sex in Ringworld Engineers was horrifying, both for its sexism and for its lack of scientific rigour.

(As for the discovery that the male kzin have been breeding their female offspring to become subintelligent wives/mothers so that only the male kzin will have intelligence… Niven was never less appealing than when he was being too sexist to think through scientific facts about heredity.)

But Ringworld itself – with Rama, one of the classics of Big Dumb Object sci-fi – still charms.

And honestly, Teela Brown and her luck are still satisfyingly scary.

@11: No problem. Glad you liked it.

Speaking of Niven’s shorter works, “The Outer Limits” (1990s version) did an adaptation of his “Inconstant Moon,” and did a good job of it.

Hi

Thought I would chip in. I enjoyed the fact that your overview included not only Ringworld but Known Space as well. Niven many have been a bit uneven over the course of his career, a bit like Heinlein in that both their personalities began to overshadow the later books. That said I enjoy his early work and I have read comments by several British writers of the New Space Opera acknowledging the important of Niven and especially Ringworld in constructing their own future worlds. But as much as I think Ringworld to have been important to science fiction what I love from Niven is his aliens. The Moties were the best part of The Mote in God’s Eye and he also gave us, among many others, the Kzin, Pak, Thrintum, Bandersnatchi and the greatest alien, in my mind, in science fiction Pierson’s Puppeteers as depicted by Peter Jones for the cover of Neutron Star.

Happy Reading

Guy

Well, without invoking his own laws, I’ll point out that biologically, the Kzin are not Earth-felines, and that it isn’t impossible for them to have some different degree of dimorphism than our own experience. There’s a few other authors who have explored the idea, some in the other direction as well.

@18 Niven is also known for “Niven’s Laws”, a set of observations regarding Scifi and writing in general. Niven’s Laws

Some of these should not need to be stated, but for those of us older than a certain age, it appears that the younger generation is not paying attention to the lessons of the past.

Ringworld definitely forms part of a collection of mid-century SF—along with Foundation, Forbidden Planet, good chunks of Star Trek, and a host of other titles I’m forgetting—that fans of the genre should probably experience for their influence and sheer high-concept awesomeness but with clear warnings that they have not always aged well. Yet some of the ways in which they now seem cringe-worthy are actually interesting elements of discussion in themselves, as reflections on the genre, the industry, and the wider culture.

(Although I found that a recent re-read of Niven’s The Shape of Space anthology holds up better than I expected. Maybe there is something to the idea that Niven and others were better able to execute idea-driven stories in smaller doses.)

One thing I particularly remember about Ringworld was how much we learn about the Puppeteers, because they are truly one of the most alien races out there. Most SF races seem to be exaggerations of various human cultures, but the Puppeteers…I mean, it’s a bold move to try and create a society where cowardice and blackmail are virtues, yet Niven makes it work pretty well, to the point where it totally makes sense that such a species would end up producing the most desirable spacecraft hulls! They are just one of several high-risk, high-reward concepts in the book that make it worth the effort in spite of its various flaws

If you want more Ringworld – have a look at the “….of Worlds” books starting with “Fleet of Worlds” that picks up the narrative and eventually gets round to the fate of the Ringworld….

It seems to me a question never answered in the Ringworld series (or the ones I read) was “why, of all possible designs for a large habitat, would someone pick one as unstable as a ringworld?”. But then one notices it is stocked with _Pak Protectors_. And one wonders if perhaps the beings who built it might not have been Outsiders who wanted to make sure if their little experiment went south on them, they could drop it into the sun. Given they get everywhere, you can never go wrong blaming weird crap on the Outsiders.

It’s interesting how much opinion diverges on when Niven went sour. My choice is considerably earlier than other people. I thought A World Out of Time was his last fun book but when I reread it, I found it was not as much fun as I remembered. In fact, Ringworld itself might have been the inflection point for Niven’s fiction. It’s the one where instead of the working class protagonists of A Gift From Earth or World of Ptavvs, the lead is a cranky rich guy.

I have in my library two books by Larry Niven – The Smoke Ring and The Integral Trees – that I remember thoroughly enjoying. Some sort of floating world with no gravity -do they stand up?

@26 Those two books are very good, some of the Niven’s best. I can’t remember quite how the torus of atmosphere exists, but the idea of humanity living in a gravity-free environment, where trees and other vegetation float like islands, is quite entertaining. Who wouldn’t be intrigued by an environment where people can fly?

26, technically I believe everybody is in freefall, but there are some tidal forces in play that do allow standing in the equivalent of a low-G environment.

If you want an alternative Known Space, Niven was about to Change Everything just before he got the idea for Ringworld.

The details are in his 1977 sf-lovers posting Down In Flames available in the link.

Thanks for a great post. I really loved Ringworld and the other early Known Space stories. Niven does create some very interesting aliens. My only mild complaint about the post is that you needed to cover Rendezvous with Rama since we just had a cylindrical interstellar object (1I/2017 U1 now known as Oumuamua) pass thru our solar system.

@26-28: There are some slides concerning the real physics of the Smoke Ring and the Integral trees starting here.

@22: I assume those are meant to be comical? If Niven really advocates for allowing passengers to carry weapons onto aeroplanes, that’s frankly disturbing. Best that those laws are consigned to the dustbin of history, I feel.

One of the most interesting things I read about Niven was his appearance at a convention where he loudly castigated TV scriptwriters for “making millions whilst we prose writers scramble for peanuts”, despite the fact that Niven was independently (very) wealthy and by that time was a bestselling author making millions. An interesting thought process at work there.

32, many people learned the wrong lesson(s) from that event, and still are foisting it off on us(though I can forgive some for more earnest mistakes than others), but I can’t blame him for pointing out the money issue, which was actually a concern for other writers, not simply about himself.

It seems to me a question never answered in the Ringworld series (or the ones I read) was “why, of all possible designs for a large habitat, would someone pick one as unstable as a ringworld?”

I always assumed that the Slavers must have built the Ringworld, since they’ve already been established as a) very rich and powerful b) very greedy for land and c) not very bright. The Pak settled it, much later, because they were desperate, but they’d never have built it themselves.

My favourite of his was always Protector, though the implausibility of humans being descended from Pak really gnawed at me…

One of the best lines in the book comes in response to someone calling Speaker-to-Animals “cute.” “I do not mean to give offense,” he replies, “but do not ever say that again. Ever.”

He also, later, gets the line “Your actions are tantamount to a declaration of war against the patriarchy!” which deserves to be on T-shirts.

Humans are manifestly related to other tetrapods, so the idea that we’re from another planet is obviously nonsensical (even in the context of Known Space, where aliens have very different body plans from ours). The obvious save is the Inherit the Stars save, where someone transported hominids from Earth to Pakhome, where they evolved or were engineered into the Galaxy’s Greatest Monsters. Whoever organized the migration back to Earth must have come across records revealing there was Pak-suitable world out towards the edge of the Milky Way.

(It’s also possible the core explosion is someone’s attempt to deal with the Milky Way’s Pak infestation before it spreads to other galaxies)

35, the Pak obviously transported their entire biosphere to Earth, which was compatible because the planet had a similar origin with the Tnuctipun/Thrintun yeasts.

Now the Martians, that lifeform I can’t explain.

Martians are stranded starfarers, which is why the ecosystem of Mars is so simple: it’s what they salvaged from their starship.

As though to illustrate my essay on authors independently arriving at similar destinations simultaneously, I submitted an essay on Big Dumb Objects the day before this essay on Ringworld went live….

Beth @@@@@ 13: sorry you had a bad experience with Niven. I think his politics went south once he started hanging with Pournelle — but I remember him just sitting there with a rueful look on his face when we savagely parodied that connection at a Boskone musical, instead of storming out the way some authors would. Alcohol probably didn’t help either when you met him, or he may have changed with age.

I’m not sure Ringworld was his peak — it certainly wasn’t the end of non-wealthy leads (cf the characters in Protector) — but I found Integral Trees a very dull slog and haven’t read any of his later solo works.

It wasn’t Niven who railed about screenwriters getting overpaid. It was Pournelle. Both turned writing SF into useful and profitable side hustles; Pournelle went from aerospace engineering to SF to being a psychiatrist to being a professor at Pepperdine and then back to writing when his drinking kept him from tenure at Pepperdine.

That said, both of them bought their houses in an historical down-market, Pournelle turned his half of the six figure advance for Lucifer’s Hammer into a beach house in San Diego at the height of the OPEC embargo, and neither of them were ever in a situation where a missed royalty payment would trigger missed meals (a fact that Niven has admitted!)

What I noticed is that both of them (and a lot of other writers of their era) basically avoid emotional immediacy in their writing. If you aren’t being glad-handed by the BDO…you notice the flat characterization and the ‘plot finger puppets’.