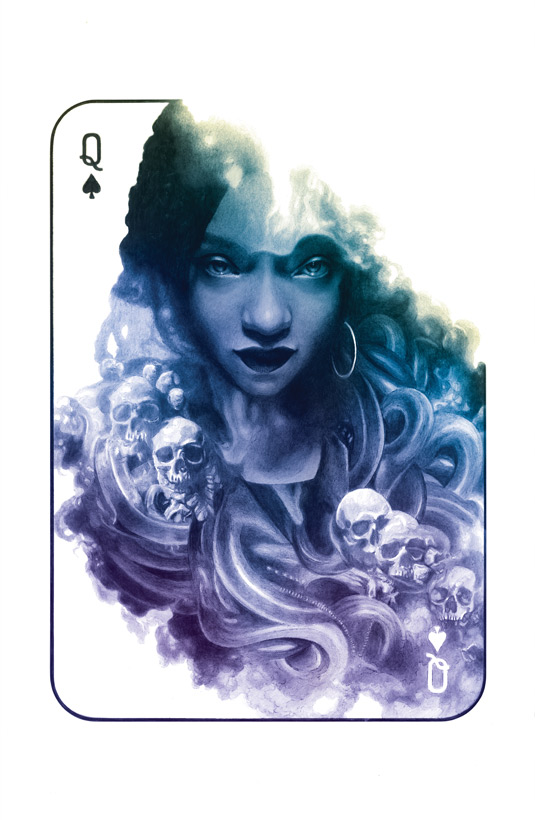

The Wild Cards universe has been thrilling readers for over 25 years. From the darkly brilliant imagination of Victor Milán, the novelette “Evernight” takes readers down to the depths of the Parisian catacombs.

Candace Sessou is known to be many things: the ace known as The Darkness, a skilled negotiator in the field of diplomacy, a refugee with neither home nor family after fleeing a war-torn Congo. When she hears that her brother Marcel also survived but is now on the run as a wanted terrorist, Candace tracks him to the Parisian underground… only to strike a deal with dangerous forces in order to save both their lives.

Candace walked between walls of stacked bones and skulls, and was afraid.

It wasn’t the darkness that scared her. Though it was the total darkness of a place light never touches, her eyes saw clearly, if in tones of gray. She could see even through her own Darkness, as nothing else on Earth could unless she temporarily shared the gift. Darkness was, if not her friend, her intimate and tool.

It wasn’t the bones that scared her, either. She put out a hand and let her fingertips trail along knobbled walls of crania and condyles, and felt nothing: they were stones to her. She knew death too well. Through her actions, if not directly by her hand, she’d left a few rooms’ worth of bones to bleach beneath the African sun, herself.

For five years Candace had known her brother was dead. Then last night, in a dive bar in Atlanta where she was doing a job for the Miami Mob, she’d seen his grown-up face on CNN, wanted for a terrorist attack in Paris.

Getting an entrance visa and a ticket on such a crash basis had blown much of the roll she’d been saving to buy her way out of that employment, which she’d entered unwittingly. But she wasn’t thinking of that now.

She feared for Marcel. She feared the unknown she was walking into. She feared what the children of perpetual night might be doing to Marcel—and what he might do to them. Because she knew from her own experience the rage that bubbled within him.

It was that fear that drew her irresistibly on, through the domain of the dead.

Chill water sloshed around the ankles of her hiking boots. She stayed out of it as much as she could. She told herself it was leakage from the city above, not seepage from the sewers that laced Paris’s underside even more completely than the ancient limestone mines and the ossuaries which took up a small part of them did. But the smell suggested that wasn’t the whole truth, sadly.

She also smelled death. It had been since the Catacombs’ mute, dismembered occupants had come here for even that persistent stink to linger. But Candace knew her death-smells, of every stage of decay. Death was here. Recent death. Probably of a rat or cat. But death, all the same.

She smelled mildew and mold and rat turds. She smelled stale human grease and dirt, and the rot that afflicts people who are still alive, if often in such an existence as not to merit the term living. And all of it—the smells, the closeness of the walls, the unfamiliar sensation of uncountable tonnes of soil and cement and stone hanging almost on top of her—conspired to give Candace Sessou, The Darkness, internationally wanted terrorist ace, a raging case of the creeps.

The Catacombs of Paris was a tourist destination long-popular because of the macabre overload induced by the spectacle of hundreds upon hundreds of meters of walls made from the dried skulls and bones of literally millions of the dead. The walls had a special name: ossements.

But this wasn’t the underworld’s tame tourist district. Candace wasn’t here to sightsee. And she was well aware that she was entering a domain claimed by a being of a power so fierce and expansive that it terrified not just the civil authorities, but the Corsican Mafia—and their rivals, the atrocity-loving, erstwhile secret-police and terrorist Leopard Men.

“Okay, this is actually kind of cool,” she said out loud in English, which she’d gotten used to speaking every day, as she hugged a façade of faces void of eyes and flesh, trying to skip over a wide spot in the stream and succeeding somewhat.

Something stung her left ankle, above her hiking boots and thermal socks, inside the leg of her pants.

She jumped and failed to entirely stifle a most un-terrorist-ace-like squeak of startled terror. Do they have scorpions down here? Venomous spiders? Before coming down here she would have ridiculed the very idea that Paris, the ultra-civilized heart of sophisticated and homogenized Europe, could possibly harbor creepy-crawling horrors to compete with what she was accustomed to finding even in the well-manicured and prosperous Kinshasa suburb where she’d grown up.

The sting had forcibly reminded her that almost literally anything could be living down here among the dead.

She caught herself thinking, Well, I might and I might not. Followed at once by, Where the Hell did that come from? She looked around uneasily. She saw nothing but bone walls and the water flowing along the limestone floor. She was actually tempted, briefly, to whip out her burner iPhone and use its flashlight app to look to see if her darkness-piercing vision was missing any nasty bugs.

Was that a ripple in the water? She squelched an urge to hop away. Just your imagination. You’re letting the stress get to you.

But the stress was real. She had no idea why her brother had defied the Leopard Men’s current policy of avoiding overt terrorism in favor of pursuing lucrative, conventional crime. If he’d even been behind the midnight bombing of an empty bus kiosk, which seemed pretty pointless any way she looked at it.

Marcel’s likely mental state worried her too. As a child he’d always been afraid of the dark, with a touch of claustrophobia. She’d never been—until now. This place was enough to get to even an ace-powered nyctophile.

And who was hunting him, to make him desperate enough to seek refuge in a realm called Evernight? She knew why to fear the Leopard Men: they’d stolen her from her childhood and tortured her until she either died or became an ace. What Paris’s African refugee community had told her about the antiterrorism unit GIGN didn’t make them seem much kinder.

She started moving forward again, staying as close to the ossement on her left as possible, and avoiding the water as best she could. She also feared what he’d found down here. Or what had found him.

A thing which she knew was trying to find her own way towards. No pressure.

Navigating by touch, keeping her eyes on what she hoped was the naturally rippling stream, she made her way toward the Queen of the Underworld’s likely seat of power.

She had lost six hours already to the need to sleep. She’d also eaten up precious time to use her phone for some research, followed by some tentative connection. Two groups defiantly explored the Parisian underworld’s hundreds of kilometers of Catacombs, mines, and sewers forbidden to the public. The Urban Experiment—les UX—considered themselves cultural vigilantes, restoring lost and neglected areas of the great city above ground as well as below. As paranoid as the UX abbreviation they went by was precious, they’d refused all communication. The Cataphiles, though, were cheerful urban explorers, ever eager to share their illicit experiences with outsiders. Some were more than a little publicity-hungry. As lamentable as Candace found that as OpSec—if the cops really wanted to shut them down, it’d take an afternoon—it served her well.

They’d responded readily, first to her also-disposable Gmail account, then by texts. The Cataphiles and the UX had come to terms with the mysterious joker-ace queen Maman Nuit-Perpetuelle and her shadow domain. She preferred to use the English word Evernight for her domain as well as herself, they said.

Candace’s day job—the one she was trying to get out of, and had now stuck herself back deeper in—mostly involved negotiation. Deals were made.

Luckily, Mama Evernight wasn’t eager to kill or disappear anybody. She had ways of warning trespassers—and not just when they were actively in her domain. Many of her “children,” as they called themselves, spent some or even most of their time aboveground, engaged in panhandling and petty thievery—as well as in spying and serving as emissaries for their secret queen. But if you pushed her—you went down into the Dark, and were seen no more.

“I just hope Mama doesn’t think I’m defying her,” Candace said out loud. Though she’d long thought herself a loner, she was starting to feel too much alone, here, with only dead-people parts for company.

Something stung her again, this time in her right ankle.

She let out an involuntary yip of surprise and fear. Looking down, she saw to her horror that something sinuous and thin had snaked out of the ripple of leakage-water and up inside the leg of her slacks.

Wishing desperately for a knife, she tried to tug free. More tendrils came dripping from the water. She felt them slither up her leg, around it, their touch slimy on bare skin that tried futilely to shrink away, gripping with remarkable strength. The stinging sensation hit again, stronger than before, a fire in her nerves.

I have your attention now, little one. Calm yourself. If I wished you harm, I’d have caused it already. Now state your business aloud.

The words formed in her head as mysteriously as the stray thought had before. This time there was no question it wasn’t hers. Is it coming through the tendrils? “I’ve come to see my brother,” she said. Her voice was steady, or mostly so.

She knew the voice in her head was right: she was had, here and now, and no mistake. And while she was a long ways from trusting its intention—Well, if this isn’t the creature I’ve come to see, it’s the creature I need to get past to do so.

Good. I taste your honesty in your blood, your nerves.

The stinging stopped. The horrid grip relaxed. The tendrils, now a skein, thrilled their way back down her bare leg, across her socks and boots to vanish beneath the water.

Ahead of her a yellow glow shone around a curve in the walls of bones. Three figures appeared, at least approximately human. Each held a torch overhead. One held two, and still had a hand free.

“Come with us,” said the three-armed, meter-and-a-half high being covered in living, writhing slugs in a mellow baritone voice. “Mama Evernight wants to see you.”

What first drew Candace’s eyes, in the high, echoing dome-shaped chamber of skulls, deep within the twist of the secret Catacombs where outsiders never came, were the three figures who sat on plain wooden stools by the far wall, staring at her with wide eyes. Their silent, motionless regard and the skeins they held put her in mind of the Fates from Greek mythology she learned at primary school.

The middle Fate, a gaunt waif of a woman with lank dark-blonde hair, silhouetted by what seemed quite ordinary utility lights on stands by the hollow-eyed walls, spoke to her. “Mama Evernight bids you welcome to her domain.”

“Thanks,” Candace said, right before it hit her.

They’re not holding those skeins, she thought. The skeins are holding them. Formed of intertwined threads of black and purple and blue and the deep red of blood, they connected each of the three unmoving figures to what Candace had thought was a mere mound of bones jutting from the middle of the wall, at the farthest point from the entrance through which her joker guides M. Sluggo, the Archive, and dog-faced Toby had previously led her.

“You may call me the Archive,” the minute, wizened, evidently ancient man said, as they marched between ossements by dancing flame-light. Candace suspected that, while the other three likely needed the illumination, the paraffin-smelling torches they carried were meant to make an impression on her. They did.

Of her three guides into the underworld, he was the most normal-looking, aside from the fact he stood a good head shorter than Candace, which made him small indeed.

“Not the Archivist?” she asked.

He tapped the short white hair that covered his head. “No. I keep our history here. I am older even than Mama herself. Though I was among the first, who followed her here, when we escaped the sweeps.”

“The sweeps?”

“When the wild card hit, France was still badly broken, recovering from the War. It was a time of profound paranoia, in which French men and women were still brutally purging one another for collaborating with the Nazis—whether they had done so or not. And above all, the survivors feared plague. Paris had been spared the worst of the war’s ravages, but elsewhere in Europe, the First Horseman of the Apocalypse rode his white horse, and reaped lives.”

“I think I see where this is going,” Candace said, with a tightening in her gut. Along with the one that came from the surroundings—and the knowledge that, while the floor here was dry, the faint striations visible twining among the bones were some kind of presence that not only lived, but somehow watched.

“Yes. Parisians reacted to the wild card outbreak in unreasoning horror. Especially when most of those infected died horribly. The fact that most of those who lived were somehow twisted and transformed—and a very few given inhuman powers—made it all the more terrible. So the unafflicted folk, the nats, began rounding up all the sufferers they could catch, and conveying them to the outskirts, where the banlieues rise today.

“When Mama Evernight realized what was happening she gathered as many of the infected as she could, even the ones who drew the Black Queen, but could still be moved, and led them to the only sanctuary that remained. A place where the normal and fearful were unlikely to follow.”

“Here,” said Candace. It seemed the response he wanted by his pause, though it made her feel like Captain Obvious.

“Here,” the Archive agreed. “Down here with the dead, we made first a camp, and then our home. For the dying we provided what comfort we could, from medical supplies we stole from the upper world, as we did our food and other necessities. Or were given to us by sympathetic souls above.”

“And the others?” Candace asked, though she knew the answer. “The ones taken to the camps.”

“A few escaped,” the Archive said. “The rest were never seen again. Not the jokers nor even the aces. We—Mama’s children who are able to bear to walk beneath the light—searched for survivors for decades after. We found none.”

“We didn’t learn this at school.”

“No. It was suppressed—officially forgotten.”

“But France is a haven for wild cards! No place more than Paris. I mean—isn’t it? I saw jokers living freely on the surface.” Even gang bosses, like the Corsican who steered me down here. And I thought “Tony the Nose” was a mere Mob nickname.…

He shrugged. “When the fear and frightened anger passed, came shame. Also the American persecution of the Four Aces influenced opinion. You know us French, since you come from the Congo: we love to use the Americans as counterexamples.”

“Yes.” She didn’t bother asking how he knew she was Congolese. My accent.

“Soon after she led us down here,” the Archive said, “Mama Evernight, who had drawn the Black Queen, lay down and died. So we built her a bier of bones and mournfully left her, with a grand chamber all to herself.”

“I am Cécile Shongo,” Candace said to the woman who had spoken, using the pseudonym under which she’d entered the UN refugee-protection program, after she fled the Nshombos’ fall.

The speaker’s pallid skin was covered with weeping sores. I hope that’s her joker, she thought. She knew quite well that Xenovirus Takis-A was not infectious, and anyway, she already had it. But she had no idea what kind of terrible creeping cruds lived down here that were.

“I’ve come to help my brother. May I see Mama Evernight?”

“You do,” said another woman, middle-aged, normal-looking but for the eyes she now turned on Candace, black without sign of whites. “She lies—”

“—before you,” said the third Fate, a stout man whose apparently nude body looked like a mass of calluses jumbled together. He nodded his lumpy head at the projecting skull-mound.

It wasn’t a random heap, Candace realized. It was a catafalque of long-dried bones. On it lay the body of a woman, which appeared to have melted partially into the loaf-shaped structure, then…hardened again, like candle wax. The skeins from the three seated speakers ran to that body, which was manifestly incapable of motion. What looked like hair surrounding the flattened features was more tendrils. Candace now saw in the shadows—for while darkness was no barrier to her vision, the transition from light made it rather more difficult for her eyes to process what lay in shade than when she was a nat—that strands ran from the corpse’s sides and limbs to vine down among the bones that held her up, and vanish into holes at the base of the curved bone wall.

She looked back at the blonde, sore-covered woman, then in confusion from her to her companions. “You mean—”

They nodded and spoke in a unison somehow more eerie than one completing another’s sentences: “That is our mother, the Queen of the Underworld.”

“But she wasn’t dead,” said M. Sluggo, his lips’…appendages…writhing to a bubble of what Candace guessed was laughter. “But none of the old beards suspected she had risen, or awakened, or whatever it was, until something stung ’Tit Beni’s ankle here, and a voice spoke in his mind.”

“Li’l Benny?” Candace said. It seemed a shockingly disrespectful name for the diminutive Archive. Especially from a joker altered as extremely as Sluggo.

“My nickname before I completed my own transition,” said the Archive equably. “You know why one might be saddled with such, no?”

“You were exceedingly large?”

“I was enormous. Over two hundred and eight centimeters tall, and strong as a corpse-wagon horse.” He chuckled ruefully. “With possibly some yet to grow. They say that the wild card has a mischievous streak, that grants those whom it touches what they most desire. Though I hate to think so many people long to die in horrible fashion. So say, rather, it’s influenced by what dominates one’s subconscious at the time of changing.

“I was bookish, uninterested in sports and less in the lifetime of manual labor my father planned I should follow him in. I became obsessed with the thought that my size was a cross, and wished profoundly to be smaller. I was lucky, I suppose, in the joker I drew. Though I never envisioned becoming as you see me.”

I prayed to the Virgin to draw the Black Queen, Candace thought, because that was the only way I saw to escape the Hell I was trapped in. I didn’t get that wish. But, indeed, Darkness permeated my mind, my soul, and so….

“Apparently the wild card agrees with you,” Candace said. “You seem to have aged quite well.” He must be at least in his eighties now, in February of 2014.

“In a way,” he said. “But that’s one of the gifts Mama Evernight grants to those who agree to help her in special ways.”

She didn’t really want to explore that subject much further at the moment. “So she can do more than just sting?”

“Oh, so very much more,” said M. Sluggo. Slugs writhed all over him in merriment. He seemed a cheerful sort. Toby nodded his black and white head and let his big pink tongue loll extra-far over his pink gums and black underlip. “She can make you feel goo-ood. She spoke in your mind as she did Benoît’s that first day back, didn’t she?”

That alarmed Candace more. “Did she read my thoughts?”

“No,” the Archive said. “She cannot do that. But she can read the chemicals in your blood, and the electrical impulses which sing along your nerves—sense your mood, your feelings. And she can manipulate them in order to communicate her thoughts directly into your mind. Although she finds that strenuous, and prefers to talk through her Speakers.”

“But she seemed to respond to what I was thinking.”

“Out loud, right?” Sluggo asked.

“I guess. How did she know what I said?”

“Her fibrils can do a lot more than sting or sample your biochemistry. They hear, and smell, and taste, as well as touch. Though they cannot see; Mama is blind, which scarcely inconveniences her.”

“Taste?”

Candace thought about the whiff of sewage in the water by her boots after she left the tourist parts of the Catacombs, and her stomach turned over. Wow, I’m learning so much about myself down here. Such as that apparently I’m still capable of getting grossed out.

The three laughed, in their various ways. “Our Mother cannot afford to be squeamish, you see,” the Archive said. “Her body needs sustenance, and lots of it. In time, everything that dies below Paris, she consumes. And a great many things come here to die.”

“And her—fibrils—extend into the sewer system?”

“A rich source of nutrients,” the Archive agreed.

“How far do they go?”

“Throughout much of the ancient subterranean network that underlies Paris,” the Archive said. “Somewhere upwards of a hundred and sixty kilometers of tunnels, currently. The rest she either is still gradually infiltrating, or does not care to, for her own reasons.”

They passed an opening to a large side-passage, or possibly chamber, dimly lit by electric lights hung from the limestone ceiling. Parts of it were obscured by sheets of plastic hung from lines, or other makeshift sight barriers. In the area she glimpsed, Candace saw living people among the bones.

They were working, or talking, or just hanging out. Some faces were additionally illuminated by screen-glow from laptop computers or smartphones. Another sawed with a hacksaw at a piece of metal on a stout bench. Some sewed, some did things she couldn’t make out. Most chatted; many laughed. Children played.

Some were obviously jokers, some were not. At least one was an ace of sorts: a little girl of maybe ten squatting in a red dress with daisies printed on it, her face all solemn with concentration as she entertained half a dozen younger kids by passing a lively orange flame across her palm and over her knuckles, like a magician walking a coin over her hand.

What shocked Candace was how normal they looked, after all the dark glamour people on the surface had built around Evernight. They were clearly poor people. But they were nothing more or less. Just people, leading their lives as best they could.

“Huh,” she said. The Archive glanced up, saw the direction of her eyes, and smiled.

“Yes,” he said. “This is the real underworld. This is what Mama Evernight devoted her life—and whatever’s come after—to building and maintaining for us.”

“Not very Infernal, is it?” M. Sluggo asked.

“I’m reserving judgment on that one,” Candace said.

“What’s going on,” Candace asked what she had mentally dubbed the Three Fates in confusion.

“We speak—”

“—For Mama Evernight.”

“She connects to us with her fibrils—”

Candace forced her reeling mind to quit focusing on the fact that the words came out of the mouths of three presumably different people in sequence, yet as smoothly as if spoken by a single person, and concentrate on what Mama Evernight was saying through them.

“—and stimulates the words inside our minds, in a way familiar to you by now. We also supply whatever trace nutrients are currently needed to keep her and her fibrils aware and functioning. In return she stimulates in us a profound sense of well-being.”

Great, Candace thought. Mama’s Milk is morphine. Well, whatever works.

“I’m no physiologist,” she said, understating mightily as curiosity got the better of judgment, again, “but it seems like she—you’d—need a lot of processing capacity to handle all the information your, uh, neural network provides you. And even in your current condition”—whatever you’d call it—“don’t you need more than just, uh, food to function?”

“Mama’s cerebrum has absorbed and supplanted most of the bier beneath her,” said the Archive. Though her three escorts had extinguished their torches when they entered electrically lit tunnels long before they reached Mama’s resting-place, they’d all accompanied her here.

“I have other assistants,” Mama’s serial voice said, “who share their bodily-organ functions with me. They lie in separate chambers; I call them my Sharers. Those who converse for me I call, unoriginally enough, my Speakers.”

Madly, Candace wondered what Mama called those who handled excretory duties. Never mind, she thought. I don’t need any asshole jokes just now.

But she felt compelled to gesture at the walls and say, “Are they—?”

“Compensated, among other ways with a deeper sense of bliss than my Speakers are. After all, the Sharers not only do not need to move, they do not need to. And yes, most of them are voluntary.”

And yes, you’ve reminded me how absolute your law is down here, Candace thought. “I’m told my brother is here,” she said. “I need to see him, please. I—I haven’t seen him in years. I thought he was dead.”

“The fugitive from the Leopard Men,” Mama said.

Candace nodded.

“He is here, and safe. He brings danger with him. But I shelter him.”

“Why?”

The three Fates shrugged as one, which Candace had to step hard on herself to keep from dissolving into hysterical laughter at. Not because she was afraid of offending Mama Evernight. Because she was afraid she wouldn’t stop.

“In a way, he belongs. He is one of my children: he’s broken. Too broken to function on the surface. Evernight isn’t just for jokers, you know. You, an ace, are broken, too, or you would not be here.”

Seeing Candace’s expression through her Speakers’ eyes, Mama said, “How could I not know? I tasted your blood, child. How well I know the bittersweet tang of the alien virus.”

“What about the Cataphiles? Are they all broken, too?”

“Not in the profound way you and my other children are. They are but hobbyists, and never penetrate to this side of the secret entrance they showed you from the Gate of Hell area. Not if they do not wish to receive a brisk warning—at best.”

Candace moistened her lips. Despite the humidity down here, they had grown rather quickly dry. “May I see him?”

“Yes.”

Candace felt her whole body slump as tension gushed out of her. She actually swayed, once, as she stood. “Thank God. And thank you, Mama.”

“Wait and see. Now, as for your ace: you need not divulge your powers at this time, since you clearly do not wish to do so. I try to allow my children the greatest possible freedom. However, though you have comported yourself well so far, I must urge you to continue to act in strict accordance with the laws of hospitality. Specifically, the duties of a good guest, which you are in our house—my house.”

So I’m a good girl, am I? I’ll show you, you sanctimonious cadaver. She held her head higher and stared Mama Evernight in the hollowed, ossified eyelids where her eyes used to be. “So long as I don’t feel threatened, I’ll behave.”

“Oh, I do not threaten. Rather, I warn. Briskly, as I warned you. If the situation merits it, I shall issue a second, sterner warning.”

Candace was already repenting her brief episode of oppositional defiant disorder. But not enough to let go of it completely. “And then?”

The Fates smiled. “If you keep misbehaving,” they said as one, “Mama spank.”

When her burly joker escort opened the door with a pangolin-scaled arm, Candace’s heart jumped into her throat.

It’s him! It’s really him!

He looked at her and his brown eyes got wide. But he said in low voice, “Call me Hébert.”

He spoke Lingala, a major lingua franca in both Brazzaville and its twin Kinshasa, as well as in much of the Congo River basin. They had grown up speaking it as a second language, after French. Emotion almost choked off her reply. “Cécile.”

Then tears flooded her vision, and they hurled themselves into one another’s arms so hard they almost clashed foreheads, and for a time there was nothing but hugging and sobbing incoherent endearments, the simple joy and grief of two lost children who had found each other again.

Almost nothing. The survivor part of Candace’s brain didn’t fail to notice the door was promptly shut behind her. And locked. A stout door.

Finally they broke apart in unison—in Candace’s case, at least, largely for air. With deep inhalations came a return of control. And attentiveness. Her brother’s room, she saw in a quick glance around, was tiny and spare, with bare limestone walls enclosing a bed, a chair, a writing desk, and even a flush toilet. Not bad, she thought. For a cell.

“Sis,” Marcel said in French, with the tears still streaming down his dark face. “You’ve got to get me out of here.” He spoke French now. His earlier use of Lingala meant he thought Mama didn’t know that language—and was probably listening.

“First,” she said, forcing her mind and soul to steady, “you need to tell me how you came here. How the Hell did you wind up with the Leopard Men?”

“The same as you did,” he said, with an alkaline rasp. Lingala again. “They kidnapped me. It was when they rounded up Mama and Papa for liquidation for asking too many questions about what happened to you.”

Candace clamped her mouth down on the puke that tried to gush up from her knotting belly. Knowing intellectually what had happened to her parents was one thing. Having it confirmed…But you “knew” Marcel was dead, too. Hold onto that.

“It was your success in their child-ace force-growing program, you see. They wanted to see if you and I shared a predisposition to draw an ace from the wild card.”

That rocked her back in horror. “They dosed you with the virus?”

He shook his head. “I didn’t pass their preliminary tests. They were only looking for candidates who might become not just aces, but a highly specialized kind.”

“Were-leopard.”

He nodded and continued in French. “They kept me on anyway. They needed somebody to clean their latrines and wait on them—that was beneath the dignity of one of Alicia Nshombo’s crème de la crème, you know? When it all came crashing down and they had to flee, they took me with them. Because they still needed a lackey.

“By the time the group that had me made its way here, they’d found a new use for me. They were already building a new organization to carry on the Revolution. But they discovered I liked to learn and do book things, and that turned out to be more useful to them than shining their shoes and cleaning their weapons. By the time I turned thirteen, I was accountant for Léon. He’s chief of the Leopard Men cadre here. He’s a true Leopard.”

“A shape-shifter?” Candace sucked in a sharp breath. Supposedly the were-leopard ace was Alicia’s own: the power to grant the gift of shape-shifting to a few, fanatically loyal, especially gifted followers. And supposedly it died with her. But it hadn’t.

There were never more than a handful of true Leopards. Fewer survived the PPA’s fall. Any are too many, she thought. “I’ve heard of him,” she said. She forced a shaky smile. “I can believe that’s what they wound up having you do. You always were the studious one.”

The Leopard Men who ran the child-ace horror camp were the kind of swaggering bullies, not necessarily stupid but aggressively anti-intellectual, who’d taken to calling themselves “Alpha” in the USA. They’d find clerk-work womanish and weak.

He grinned. “And you were always frivolous, hein?”

She shrugged. For an accountant, he’s turned out pretty sturdy, she noted. Apparently even being a clerk for the Leopard Men’s shiny new criminal operation was strenuous. Once a runt even shorter than she was, at seventeen he’d shot up to 172 centimeters, seven taller than her, and filled out considerably. More wiry than bulked-out, but well-packed with muscle.

“So why did you blow up a bus kiosk? That’s the kind of no-question terrorist attack my contacts tell me the Leopard Men have been staying away from since they got here. Also, it was lame.”

His smile got wider. “It stirred up the French, though, didn’t it?”

“The Western powers are all paranoid about terrorism. The idea someone might do to them what they’ve spent centuries doing to us terrifies them. Which I guess makes sense. But all the more reason to ask why they had you do such a thing, when the Leopards’ve worked so hard to make themselves look like nothing more than a criminal gang elbowing for power in the big city.”

“They wanted to test my resolve. Also send a message to the Corsicans, the Maghrebi out in the banlieues, and the Traveler mob what could happen to them if they kept trying push the Leopard Men off the top of the heap.”

That’s stupid, Candace thought. And utterly characteristic of Leopard Men. She was lucky, in a perverse way, that her training had been mostly masterminded by the American ace Tom Weathers. Who even if he did turn out to be just another brand of evil imperialist, and crazy to boot, was a thoroughly professional revolutionary terrorist. And an experienced one. He’d taught her well. “So how did you wind up here, of all places?” she asked. “You’ve always been afraid of the dark.”

“I freaked out. The blast scared me so much I shit my pants and just ran. That’s why I’m wearing these castoffs the Evernighters gave me. The hole I ducked down brought me straight to Mama’s people.”

I was wondering why you were dressed like a street beggar. The Leopard Men had always been sharp dressers, affecting dark suits and neckties even in the hot, humid Congolese bush.

“I guess they were right to test me, no? Because I failed. When I calmed down, I realized they’d figure I was going to sell them out. And I’d heard of this place. You can’t be on Paris’s underside and not. We—the Leopards and I—even knew where some of the entrances to Mama’s little kingdom were. Why not? It wasn’t as if even they dared to try to come to Evernight without permission.”

“Which Mama wasn’t about to grant them.”

“Oh, no. She hates terrorists. She doesn’t like plain violent criminals much better.”

“So why did they take you in?”

“They said it was because I belonged here. I was broken, as they put it: a young, exploited kid, forced to do things I didn’t want to, scared shitless—literally—and looking for a way out. A refuge. Evernight’s all about refuge. So they’re sheltering me. Even though it’s bringing the exact kind of heat on them that Mama’s tried for years to avoid, they tell me.”

“Are you worried they’ll turn you over to the authorities?”

“They’d never turn anybody over to les flics. Mama’s even more absolute than the Corsicans about that. If they decide I’m really a terrorist, they’ll just send the National Police my head, along with a note handwritten by Sortilége. She’s one of Mama’s Speakers, even though she’s mute. She only communicates by Tarot readings and writing on an Android tablet. She has really beautiful penmanship, I guess.”

“Is that why you’re so eager to get out? It looks to me as if this place is just what you’ve been hoping for: a safe haven.”

“Sis, it’s the closeness. And the dark. You remember. I always slept with a night light, and you always used to tease me.”

She grinned. “It was my job as your older sister.”

“You didn’t have to enjoy it so much. But—I guess I have a touch of claustrophobia, too. They kept us locked in cargo containers when the Leopard Men first smuggled me into France, as many kids as they could cram in each. A lot of us freaked out. I did. But I never fell to the bottom of the heap and suffocated, anyway.”

She shook her head. The Nshombos and their goons had so much to answer for, she thought. But, on the bright side, most of them did.

He grabbed her hands. The tear-flood had started down his cheeks again. He was still full-faced, as he’d been as a child, although clearly not from boyhood pudge anymore. “Please—Cécile. I beg you. I’m going mad here. You’ve got to get me out!”

She squeezed tightly back. “Leave it to me.”

“Mama’s children say they don’t dare let me go! What can you do?”

She smiled. “In my current life,” she said, “you might say I have become a professional negotiator, of sorts.”

Yes, the words written on a Samsung Galaxy Tab 2’s 254 mm screen read. I will release your brother. If you will do something for me.

She really does have exquisite handwriting, Candace thought. Even with a stylus on a screen.

A new trio of Speakers now surrounded Mama on her catafalque. One was the fortuneteller with the long, lank blonde who called herself Sortilége. By no coincidence whatever, I’m pretty sure.

“Tell me,” Candace said.

“You know about the Groupe d’intervention de la Gendarmerie nationale?” asked another Speaker, a pallid kid with black emo hair hanging in his almost-as-black eyes, and a Pinocchio nose she was pretty sure he hadn’t been born with.

“Of course. Who doesn’t?” What kind of properly trained terrorist would I be if I hadn’t heard of GIGN? “They’re the special-operations branch of the national military police.”

“Yes,” said a green-skinned older woman, the third of Mama’s current interpreters to the outside world. “Their Paris squad is especially brutal. And they have nearly talked the civil authorities into launching something they’ve wanted to do for years.”

An operation to wipe out Evernight, Sortilége wrote. She even wrote the underworld domain’s name in English. Candace suspected Mama called it that partly to piss off the surface city’s stick-up-the-butt Académie française language-fascist types.

“You don’t mean kill everybody?” she asked. “How would they get away with such a thing? This isn’t off the scope in the Third World—some corner of Africa nobody in the West knows or cares about.”

“Isn’t it?” asked Scene Kid. “What comes down here is buried. It’s been that way since the Catacombs were formed.”

At the very least, they mean to murder Mama, Sortilége wrote.

“And that would mean death for all of us, as sure as by shooting,” the green woman said.

Candace frowned. She was no bleeding-heart, as the Americans would say. She was certainly no revolutionary—her adventures in the Nshombos’ Holiday Camp for Wayward Child Aces had burned any inclination in that direction right out of her. But now, she suddenly discovered, there was still some shit she would not eat.

And not incidentally, the practical side of her brain reminded her, it would mean Marcel’s death as well. “But what can I do? I’m just a tourist!”

We need you to negotiate on our behalf, Sortilége wrote.

“—With the Mayor’s Special Aide for Wild Card Affairs.”

“We understand you are a skilled negotiator, in your day job back in Canada,” added Scene Kid with more than a bit of a smirk.

She glared at all of them in turn, resenting the bald admission of the eavesdropping she’d taken for granted would happen. And then for good measure at Mama Evernight, although she could no more see with her fibrils than her long-dead and withered eyes. “How do you expect me to do that? Just march into City Hall and say, ‘I’m Cécile Shongo and I want to see the Mayor’s Special Aide for Whatever the Fuck?”

“Yes,” the green woman said blandly. “You have an appointment.”

Sortilége held up a smartphone. Candace’s phone. The sender’s name on the SMS message display read Boumedienne.

“We have her number,” the Speakers explained. “We deal with her frequently. But this matter is delicate and requires negotiation face to face.”

Candace sighed. This place looked and felt so much like something of a nineties horror flick that she had difficulty remembering it was the twenty-first century, even down here. “What’s in it for me?”

“Freedom for your brother. And you, of course. On condition that he perform no more violent acts. And you must get him out of the country within twenty-four hours.”

“Deal. It’s been real, but there won’t be a lot keeping me here after he’s free.”

“One more thing,” Green Woman said.

You must answer for your brother’s compliance with your own life as well as his, the Galaxy said. If he violates these conditions—

Her other hand held up a card depicting a skeleton in plate armor, riding a white horse. Candace didn’t know much about the Tarot, but she did recognize a Death card. Even without “Le Mort” helpfully printed at the bottom.

“I’ll do it,” she said.

With its colonnaded walls and high, round-arched ceiling the Hôtel de Ville looked to Candace more like a big train station decorated in Fin de Siècle Whorehouse–style than City Hall for a metropolis.

The two white dudes in the dark suits tailored close enough to display their brick-like physiques, if not the handguns in their shoulder holsters, with dark sunglasses and earphones struck to their bald-shaven, brick-like heads, who immediately detached themselves from the columns to march purposefully toward Candace, couldn’t have looked more like Official Thugs if they were on a poster for next summer’s big action blockbuster.

Dark them! screamed in Candace’s brain as fear electrocuted her. Dark the whole room and run! Cut their fucking throats, to be safe! She’d scored a sweet lockback-folder knife from Toby for a not too extortionate price, and apparently the Paris City Council thought metal detectors on the entranceways wouldn’t fit in with the Giant Fantasy Renaissance Castle look of the building’s exterior or the gaudy insides.

She forced the voice of terror to shut the fuck up and sighed in resignation.

“Mme Shongo,” said the slightly taller goon, “we need you to come with us.”

“What are you doing?” she yelled at the top of her lungs. “I’m a Canadian citizen! I have my rights!”

The other goon suddenly materialized—metaphorically, not literally, a distinction you always had to make in a world where any random could be an ace—at her left elbow and pinched her above it with what might as well have been an ace’s steel claws.

“Not with us, little girl,” he said softly in her ear. “So, do you do this the easy way, or the fun way?”

She let her shoulders slump. She knew she didn’t have any rights—not with guys who looked and dressed like that. But she did have a cover to maintain. “All right,” she said back quietly. “I’ll come with you. You can’t blame a girl for trying, though.”

“Of course we can,” said Thing One.

“What are you doing here?” the tall white man in the light gray silk demanded. He was the only one among the seven white men in the room whose suit wasn’t black, and the only without a clean-shaven scalp. His buzz cut had the look and color of steel shavings. “Why do you come to see Mme Boumedienne?”

“I told you,” she said. “I came here to help a friend who got in trouble with the law and wound up in the Catacombs.”

They had forcibly sat her down in the middle of a small but fancy room, overheated by a musty-smelling radiator painted white. It was somewhere down a rat-maze path, into a wing of the sprawling structure that pretty clearly saw little use these days. They hadn’t tied her to the antique, Louis the Something-Ass–looking chair, but they had thoughtfully spread a blue tarp on the floor beneath it.

Buzz-Cut bent down, grabbed the chair arms from her right, and spun her to face him. “Do you know who I am?” he hissed in her face. His breath had a strange smell, strong, astringent, and not at all pleasant.

“You are Colonel Emmanuel DuQuesne of the GIGN,” she said. “Head of Section such-and-such I didn’t bother to remember. You introduced yourself when your brutes brought me in.”

“Section 23,” he said, straightening. There was something odd about his voice, something she couldn’t quite pin down. As if he had something in his mouth, was the closest she could get. “It is a name synonymous with terror. Terror prevention to the media. And to everybody else…” He smiled unpleasantly. He was not a man who struck Candace as one who did a lot of things pleasantly.

She knew the type.

“You’re not here to help the black terrorist rat who dove down into the sewers the other night? He’s a Congolese, we know. As are you.”

“I’m Canadian now,” she said levelly. “I’m looking to help a friend. He’s French, white, and a joker. Jacques Gendron. I met him at college in Montréal.”

By great good chance, just such a person had entered Evernight a month ago. She’d met him for the first time moments before departing Evernight by one of the countless secret ways, which happened to lie near a Métro station. Of course, she thought, if GIGN has actually tapped the Special Aide’s phone, I’m fucked.

“And on behalf of such a one, you agreed to serve as emissary for the Queen of the Underworld to the Special Aide?”

“We were close.”

He curled his lip in disgust. “So what exactly is your business here?”

“Confidential. You’ll need to ask the Mayor’s Special Aide that question. I bet she has the proper forms available online.”

He glared at her. His eyes were very dark. She expected him to strike her then. Instead he gestured to his Goon Squad. “Her leg,” he commanded curtly. “The left one.”

She was seized from behind and professionally pinned to the chair. Another goon knelt to clamp an iron grip on her right leg. Two more straightened out the left and pulled the dark-gray wool leg of her business-suit pants up to bare her calf.

“So,” DuQuesne said, eyeing her as he might the fruit at a stall in the open-air market in the Goutte d’Or, “you still display the leanness characteristic of the true African, little cunt. The softness of the North American black has not infected you.”

“I try to keep in shape,” she said. I could try and sound more terrified, she thought, but I don’t think at this point it’s going to matter.

He bent down, bringing his pale, scarred face near her bare skin. A thrill of horror ran through her. He’s not going to try to kiss me? Eww!

Instead he opened his jaws wide. Two long, curved fangs swept down and forward from the roof of his mouth, and locked into place in the gaps where his canines would be. Before she could react, he bit down hard, right into her calf muscle.

It was as if her lower leg had been electrocuted and firebombed at the same time. She convulsed and shrieked so loud it tore her throat.

He stood up, looked her in eyes now brimming with tears. His fangs clicked back into place as he closed his near-lipless mouth on a look of obscene satisfaction.

“They call me La Vipère,” he said. She knew now why he talked funny. “For, like a viper’s, my bite carries venom. Do you feel it burning in your veins?”

“Yes!” She managed not to shriek it.

Agony was not a new sensation for Candace Sessou. The child-ace factory had used “therapeutic” torture to stress its subjects, to encourage the retrovirus to express in them as an ace. But not pain like this. It felt like lava blooming beneath her skin.

“My ace,” he said, “allows me to inject a blend of such a strength and composition as I choose, within certain limits. In your case: a mild dose of proteases with a neurotoxin kicker. I could inject enough nerve-killer to stop your heart—or enough protease venom to explode the blood cells throughout your body in a rolling tide of unendurable agony. You think you screamed just now? It’s nothing.”

“Why are you doing this? I told you all I know!” Please believe me, she thought.

She knew she could Dark them—or she could, provided the pain died back enough to let her concentrate her will. But that wouldn’t get her out of here. They didn’t need to see to hang onto her. Or for this sadistic madman to bite her again.

“Have you? Really?”

“Yes!”

He nodded. “So be it. You must be telling the truth. Such a slip of a girl could never hold out against even so minor a pain. Let her go.”

Let her go? She couldn’t believe she’d heard him right. But the GIGN men released her legs and arms and stepped back. She slumped forward in her chair. She stopped herself from grabbing her poisoned leg. She wasn’t sure if that would increase the damage the venom did. Or cause it to spread.

It did burn less now. A little. I can…manage.

“Are you still here? Up. You’re free. Get your black ass out of my sight before I nip you there to encourage you to move it.”

“Why did you do that to me?”

“There will be no lasting damage, I assure you. Well, very little. You should be able to walk now. As for why—well, yes, to assure myself that your story was true, far-fetched as it seems. Also I wanted to make sure you weren’t hiding any ace powers—such people are dangerous. Of course, if you had any such, you’d have used them in an attempt to escape the agony. Futile, of course. But you couldn’t have known that.”

Want to bet? she thought.

“Also, to impress you—and your monstrous mistress below the ground. Her powers and mine are not so very different, you see. We both possess a potent sting; we have likewise senses the average human does not. We share the gift of manipulating human biochemistry. Even if I lack her power of using neurochemical interfacing to control the human mind.”

Which Mama can’t do. Well, told me she can’t. I may have no more reason to believe her than I do this…reptile. But guess which one I’d rather trust?

“And finally—” he smiled and let the fangs snap down again briefly—“for the fun of it. This is a stressful job I have, keeping Western civilization safe from savage animals. You can’t begrudge me a little sport, can you?”

“This program is far advanced, I regret to say,” the Mayor’s Special Aide for Wild Card Affairs said. “Much against our wishes, as I trust you understand. Our mission is to help people, not—anyway. Tell me what Mama Evernight has to offer, to induce me to do more to stop this tragedy than I have already.”

Maryam Boumedienne was a handsome, gracefully dignified woman of North African descent. She stood a head taller than Candace and was willowy despite clearly being well into middle age, with hips broadened from child-bearing. The hair wound into a mathematically precise bun at the back of her narrow head was black showing only threads of silver.

She frowned slightly. “But first—tell me, please, what she’s offering you, to get you to agree to negotiate for her?”

“My brother’s freedom,” she said.

“Your brother the wanted terrorist?”

She shrugged. “Nobody’s perfect. But we’ll address that later. Yes. That brother.”

Mme Boumedienne’s office was positively restrained in its décor, albeit still large enough to hold a good-sized elephant or modest Brontosaurus. The walls’ bare, gleaming oak veneer, the modern-looking desk and…relatively modern…chairs, the black and white parquetry floors and simple ceiling all contrasted hugely to the frou-frou explosions of the corridors Candace had made her way through, after La Vipère’s henchmen cut her loose. Those were all ornate chandeliers and fat white women with their boobs hanging out everywhere: topless in heroic bas-relief on the walls; cavorting nude with Pegasuses on the ceiling paintings. Whoever had decorated the place had had serious issues.

The Special Aide was still looking at her expectantly. “She offers you continued peace and well-being in the city.”

“A threat?”

“No. An observation. Consider: A modern city needs its refuse dump.” She felt no shame at cribbing from one of the Archive’s lectures. “Plus an extensive sewer system.”

“Much of which has been co-opted into Evernight,” Boumedienne said.

“Well, they don’t actually live in the sewers. Or not many. In any event, consider the service Evernight provides: a catchment for those, jokers, nats, even minor aces, who find themselves unable to function in the surface world.”

“But we offer services for those poor people,” Boumedienne said. “That’s among the duties of my department, not to put too fine a point on it.”

“And I’m sure you do your best, Madame. But, with all respect, please consider what a wonderful job those social services must have done for these people, these Evernighters, that they’d choose to live in a place with bones for walls instead.”

Boumedienne winced. “Point taken. And—it’s true. We cannot provide for the particular needs of everyone. We must provide for the common welfare.”

“Mama Evernight and her children define ‘uncommon.’”

“True. But even leaving aside your brother’s recent terrorist act, as you request, there are people of highly dubious moral character living down there.”

“There is also a large, thriving, tightly knit community of people peaceably living their lives. It’s not too much to call it a family. I have seen it with my own eyes. And—Mama does enforce what few rules she has laid down quite strictly.”

“She was one of the ‘dubious characters’ I was referring to.”

“Is it worth wiping out an entire community to get at her?”

“The operation would not necessarily kill everybody down there. Despite the expressed desires of some.”

I wonder who? Candace thought. “How many do you think it would be necessary to kill, then? Whom would you kill?”

“Why, none—if it could be helped. But, but—it would be a humanitarian intervention. Some collateral damage is sadly inevitable. But in the service of the greater good.”

“Mme Boumedienne, those killed by humanitarian intervention stay just as dead, the arms and legs and faces stay blown just as far off the wounded, as in war by any other name you want to give it. I’ve seen it up close. And I tell you: anybody who thinks such a thing as ‘humanitarian warfare’ is even possible does not understand what at least one of those words mean!”

The Special Aide looked uncomfortably away.

“Let me put it another way,” Candace said. “Would you shut down the sewers of Paris because they had some alligators in them?”

“Well—they’re really Nile crocodiles. And there are not so many of them. And they do keep down the rats…”

“You begin to see my point.”

“All right. This is all very well and good. But I need more. Give me something that I can take to the Mayor—to the national authorities—which will persuade them to stay the Gendarmerie’s hand.” A beat. “Please.”

Candace leaned forward across the neat desk. “Mama abhors all crimes of violence, including terrorism. You must know that, from your years of dealing with Evernight. So she makes no threats. She merely asks you to imagine the effects on the peace and well-being of your city’s straight citizens and tourists in the event of even a successful decapitation strike: the horde of angry, embittered jokers and fugitives that would fill the Métropolitain stations and pour up from every manhole and access-tunnel in Paris.”

The pale-brown eyes got wide. “Shit,” the Mayor’s Special Aide said.

Candace sat back, nodding. “Precisely.”

Boumedienne frowned at nothing for a few moments. Long enough for Candace to start getting itchy about her brother’s fate. And her own. There are too many games going on at once here, she thought, and I don’t trust any of the players. Except DuQuesne, to be awful.

“Very well,” the Special Aide said at last. “I think I can persuade them with that…graphic image. Even the upper ranks of the Gendarmerie National—even the commanders of GIGN themselves—realize that such a measure as they propose is extreme, and likely to produce blowback. When I share your description of the nature of such blowback, I think they’ll reconsider.”

“So you agree to Mama’s terms?”

“Yes. Now, let’s talk about yours.”

“I’ve guaranteed my brother’s continued good behavior to Mama, which guarantee I likewise extend to you.” Even though you don’t seem the sort to kill me if he breaks my promise. “He will honor that guarantee. He’s desperate. Desperate enough even to behave.”

“Even so, he’s still wanted for an act of terrorism.”

“I’ve also promised Mama Evernight to have him out of the country within twenty-four hours. That would get him out of your hair.”

“‘Terrorist,’” Boumedienne repeated. “That’s a magic word these days. It makes rights and justice go away. Along with a good deal of sense.”

“That’s true. But in exchange for his freedom, he’s willing to provide all the details he knows about the Leopard Man leadership cadre in Paris—which means all of France. Names, dates, plans, the works. And he was Léon’s own accountant.”

“You mean—”

“He’ll give you their financial records, down to the PIN numbers on their pseudonymous bank accounts.”

“That—that would excuse a very great deal.”

“And after all,” Candace said, “it’s not as if anybody was hurt. It was only a bus kiosk.”

“It’s not as if anybody else was there. The only reason we identified your brother was that several surveillance cameras captured him in the act. We were able to match his face with an individual Gendarmerie agents have photographed in the company of known Leopard Men, and near known Leopard Men locations. Still—the kiosk will cost 63,000 euros to repair.”

Candace whistled. “So much?”

“You know government contracts.” Mme Boumedienne stood up and offered her hand across the desk. “All right. You have made yourself a bargain. I know the Mayor will see the wisdom of your proposals, and the President as well. As for the National Police and the Gendarmes—well, they’ll either see the light of wisdom, or do as they are told, depending. I cannot yet guarantee acceptance. But I think the chances are good.”

Candace almost deflated into a limp rubber sack like an empty balloon. “Thank you,” she said, pulling herself together enough to rise and clasp the proffered hand.

“You are a brave woman, Mme Shongo,” the Special Aide said. “Your brother cannot know what a remarkable sister he’s fortunate enough to have.”

“Probably not,” Candace said. “He’s my younger brother.”

Boumedienne laughed, but quickly went serious again.

“I only hope your courage turns out not to have been rashness in the end. Good day to you. And good luck.”

Where is he? Candace asked herself, checking her smartphone again. It was 2258. Two minutes later than last time.

It was chilly. Her breath puffed out visibly to join the mists creeping out of the Seine to fill the Place Vendôme with the smell of diesel exhaust and grease-trap rankness. The lights glowed dim and yellow, and few people walked abroad. A pair of lovers gazed arm in arm up at the statue of the flying ace Captain Donatien Racine, known as Tricolor, atop the famous column commemorating his defense of Paris from the 2009 attack by the Radical—her old crush and mentor, Tom Weathers. A shabby man—one of Mama’s children?—marched past the gate to the Tuileries, swigging wine from a bottle and mumble-singing indistinctly to himself.

Her own warm buzz of success and champagne was starting to curdle in her stomach. Should I have let him go off by himself?

Like everybody packed anxiously into Mama Evernight’s crypt, her brother had gone manically happy when Mme Boumedienne called to announce that the President himself had ordered the Gendarmerie to stand down from its planned attack. Candace’s bargain had been accepted.

I at least had sense to worry when Marcel said he was going out without me. Briefly. She’d been in a happy place she’d almost forgotten existed, swilling Moët & Chandon from the bottle like the mumbling hobo minstrel, dancing and chanting along to “La Marseillaise” echoing off the bone walls from big speakers playing off somebody’s iPod. She had the hairy arm of the two-and-a-half-meter-tall joker called Bigfoot across her shoulders from one side, and the hard, dense arm of the Mauritanian joker-ace who called herself La Brique from the other. He’s so happy and excited, she remembered thinking. Why not let him go?

She had pulled together enough to suggest that she come along and watch his back. But no, Marcel said. He had to go alone. He’d stashed thumb drives containing key financial records with a Christian refugee from the Albanian civil war, a shopkeeper who’d suffered mightily from Leopard Man extortion. He’d been planning his escape for a long time, he said.

His contact had the paranoid hypervigilance of an alley cat. If Marcel brought anyone along, he’d shut down and hunker behind steel shutters. So Candace nodded; her brother kissed her fervently on the cheek, thanked her for the hundredth time, promised to meet her in the Place Vendôme at 2100, and left Evernight.

Their flight from Orly left at 0130. Darkness was beginning to muster in Candace’s stomach, and tension knotted around the black sensation. To distract herself from her thoughts, and the growling of the terrible thing that lurked in her under-brain, she glanced up the column’s bronze, already green four years after its construction. Despite the French government’s official reversal of its initial genocidal approach toward those touched by the wild card into operatic concern for their welfare—powered both by guilt and a desire to twit the Yankees for their Four Aces witch hunt—it kept tight rein on everyone who drew the ace. Every one detected they conscripted into government service. As a consequence, France had few publicly known ace heroes to adore. Because Captain Racine’s heroics had been broadcast live worldwide on video news feeds, the government opted to make him the public face of its shadowy ace corps—and a tourist attraction.

Candace recalled her encounter with another official French shadow-ace that afternoon, shuddered, and felt unclean. Tricolor’s bravery was real. But it was being used to hide a lie.

Her iPhone started playing the signature tune from Van McCoy’s “The Hustle,” a current favorite song twenty years older than she was. She almost dropped it yanking it from her purse. “Hello?”

“It’s Sluggo,” her caller said. “Your brother’s been spotted heading for the Leopard Man HQ in the Goutte d’Or. You must come at once.”

She barely remembered to end the call with a stab of her thumb before turning and sprinting for the nearest Métro stairs.

Marcel, Marcel—what have you done?

Already, she feared she knew.

When the stench struck her like a fist through the open front door, Candace flicked her knife blade into place. She stepped cautiously out of the feather-light sleet falling on the lower slope of the Mount of Martyrs into the normal-looking two-story gray stone house, cramped on a block of near-identical houses with steep slate roofs, to which Samuel L. Jackson’s voice on her GPS had led her from the Château Rouge Métro stop at a dead run.

She opened her mouth, and Darkness rolled out to precede her. Nothing could see through it but her, and those she temporarily allowed to. A were-leopard might hear and smell her well enough to strike, but a far more likely nat gunman would see nothing to shoot at.

Not that anyone she saw was in any shape for shooting. Two bodies, male, and what she thought was parts of a third sprawled in attitudes of violent death, their own guts, and all their blood on the sodden throw rug—an oddly domestic touch for Leopard Men—the doorway that opened to her right, and the stairs themselves. An old-school AKM, heavier, and higher-caliber than modern assault rifles, lay propped almost theatrically at the foot of the stairs.

She let it lie as she passed by. She didn’t need it. Also the recoil from 7.62 cartridges and steel buttplate hurt her shoulder.

The smell was familiar. Fear and fresh blood and shit. She hadn’t smelled it for years. Except in my dreams. At the house’s rear an oblong of relative lightness showed a back door also ajar. Another body lay on its front past the stairs, with its head turned to the side. Half its head. The rear half.

“You have strong jaws, you treacherous bastard,” she muttered.

From ahead, she heard a snarling and a spitting, and she ran.

She crossed a short, bare yard that stank of pee and weed, just missed stepping on one of a litter of discarded wine bottles and falling, and clambered up onto a stone wall just higher than her head.

A narrow alley confronted her. In the next yard, two leopards fought, a larger and a smaller.

They squatted on spotted haunches, yowling and swiping for each other’s faces. Though both were covered in blood, the larger one’s left shoulder lay open to bone, blood running in the rain. As Candace drew herself upright, balanced on the rounded wall-top with the help of a couple years’ ballet classes in Cape Town, she saw the bigger gather itself and leap on the smaller.

Rather than spring to meet it, the lesser leopard rolled backward across its twitching tail onto its butt, accepting the attack with its forepaws. The larger cat’s momentum flung it all the way onto its back. The bigger landed on top, its hind claws raking at the lesser’s belly.

The smaller leopard’s jaws clamped on its throat.

A natural leopard killed larger prey by holding its throat closed in its teeth until it suffocated. But Leopard Men—the few, the proud, the weres—they loved the taste of blood. Their shared ace had given them mighty jaws and razor teeth. And what was power, if not to be used to the utmost? To be enjoyed?

With a heave of its round head, the smaller leopard ripped the throat clean out of the one atop it. The bigger one fell onto its side on the flagstones, kicking and gushing.

Candace’s heart seemed to pause its beating.

The smaller cat jumped up—and continued rising, to stand bipedal, hunched over as if in pain. To her relief and fury mingled she saw it was Marcel, naked. A taller, older African man, likewise naked, lay bleeding to death at his feet.

Her brother swayed. He was awash in blood. But Candace saw no sign of deep wounds beneath the gore.

“Marcel!” she shrieked. He turned his blood-masked face to her. Their eyes locked.

He turned and staggered around the hip of the darkened house with surprising speed. Too late, it came to her to try to Dark him. Not that I know how I’d capture him without one or both us getting hurt, if he turns again.

She jumped down from her wall, scrambled over the next, vaulted the dying Léon, and ran after her brother. He was weakened by exertion, and mostly by the stress of transforming from a seventy-kilogram boy into a seventy-kilogram cat, with its drastically different skeleton and muscles, and back again to human.

She ran out past the house and stopped. Two figures stood on the street, looking at her. “M. Sluggo,” she said, panting more than she should have. “Toby.”

Toby uttered a greeting bark. He sounded cheerful. Then again, having a dog’s head atop an otherwise-human body, he probably always sounded cheerful, unless he was growling. “Our people have your brother, and are taking him below,” Sluggo said mournfully. Or so she took it from the flaccid dangle of his slugs. “You must come with us. You won’t make us compel you, too, will you? Please?”

She sighed. “No,” she said. “Lead me to the Underworld, psychopomp. Do I need to give you a Euro?”

Sadly Sluggo shook his head. “Alas,” he said, “I have no boat. Come on.”

“You betrayed me.”

On the march down and down into the everlasting dark, and round and round through corridors of bone and stone, Candace had wondered what exactly she would say when—if—she confronted her brother.

Now the two were locked in the same cell he’d been held in before. She was as much a captive in Evernight as Marcel was. She just wasn’t restricted to this room.

She knew, now, what she’d say, having said it. But she was still surprised at how levelly she spoke.

He sneered. His handsome, earnest-schoolboy features twisted in a look of hate so pure it rocked her on her heels. “Don’t talk to me about betrayal!” he screamed. Then more quietly: “You betrayed us, Darkness.”

“Don’t call me that.”

“You and the others—the Hunger, Mummy, Wrecker—you were heroes of the Revolution, the fighting vanguard of our glorious PPA! Yet you deserted Alicia and the People’s Paradise in their greatest need. You deserted the Revolution.”

She glared at him through narrow eyes. He’s still my brother. Even after what he’s done.

“Fuck your Revolution,” she said, in a low, intense voice. “It was all a bunch of lies Alicia and her brother told us to serve their greed and power-lust. We killed more black people than the imperialists did. By far. We even murdered more of our own—people inside the PPA—than any outside enemy ever did.”

Marcel scoffed. “What about Captain Flint and the Highwayman and their living atom bomb that killed so many of our soldiers?”

“Who do you think did most of the Nshombos’ murder for them? Not us; we were few, though we murdered our share, many times over. Your precious soldiers. I don’t waste tears on them. Any more than I do the British aces, scapegoated by their own to assuage their tender colonialist consciences. I’m not saying the imperialists were good. I’m saying we were worse. Sometimes I wish we’d all died in the blast, too—us child aces. It would have been better for the world. And probably us as well.”

But saying that, she felt a pang of loss, for the other stolen ones, her comrades in living through a Hell no one should have to endure, much less children. It lent an acid splash to her next words. “The Nshombos made us monsters, Marcel. You and me both. But they were the greater monsters by far. That’s what I turned against. And I’m glad!”

“You only say that because you were the whore of the white devil! The one who misled us, and murdered the Doctor!”

“Oh, come the fuck off it, Marcel. Tom Weathers wasn’t a good man, but one thing he was not was into literally fucking children. Even though he helped your precious Nshombos fuck us all!”

And just like that, he shifted—partway. Her own reflexes were naturally fast. But she was only able to skip back and turn her head far enough fast enough that the claws at the end of his left arm, now spotted-furred and inhumanly jointed, only gashed her right cheek, instead of tearing her whole face off her skull.

That’s some great control you have there, bro, she thought as she opened her mouth and Darked him.

He screamed in leopard fury and lashed out. She backed up to the locked door and pounded on it with her palm, hoping Gros-pieds and Brick outside would realize what was happening and let her out.

He turned toward her. His head was still human. The look on his face was not. Though his arm was still transformed—he probably hadn’t recovered the energy for a full change—he didn’t have a leopard’s senses. But he didn’t need them. He could hear just fine. And it wasn’t hard to make out where she was. He gathered himself to leap. Candace made ready to dodge, hoping she was faster than his mostly human body.

The door opened behind her. Her brother shrieked as fibrils lashed from tiny holes hidden in the stone walls and tangled his arms, his face.

“Don’t kill him!” she screamed, as rock-hard hands yanked her backward into the corridor. “Please!”

“I will not,” an eerie voice said from her right.

She turned. Between bone walls stood the Archive, small and neat, bearing the distinctive multi-colored tendril leash of one of Mama’s Speakers around his neck.

“Not now, at least,” he said, the voice his own but echoing the cadence and timbre of a woman long dead—and eternally alive. “Now you must come and learn your fate.”

“Please don’t kill Marcel, Mama,” Candace said the moment she entered the Queen’s burial chamber. “I beg you. Take me instead.”

A middle-aged Vietnamese woman called Pétunia had cleaned the wounds her brother’s claws had opened on her face, closing them with a healing ace. “There might still be scarring, dear,” she’d told Candace.

Candace only shrugged. For a moment she’d thought the fact the Evernighters tended her wounds meant Mama didn’t mean to kill her. Then it occurred to her Mama might just not want Candace passing out from blood loss before hearing her death sentence.

“Your life is forfeit anyway,” said Ariane, the blonde woman covered in weeping sores. Apparently the first shift of Speakers she’d encountered was back on duty. “Along with his.”

“And yet you’d try to bargain your life for your brother’s, even after what he did to you?” That was Evadne, the middle-aged woman with the all-black eyes.

“He’s my brother. It’s not as if my life is such a fucking carnival, anyway. Just—just keep him. I know you can’t let him go. But alive. Kill me.”

Aristide, the naked, callused man said, “You may redeem your life and his. And your freedom.”

“Though as you say, your brother must remain in Evernight always.”

Evadne gestured toward a big LED TV, which had been set up by the curving wall to one side. Sortilége turned the volume up with her lower left hand.

“—Valentine’s Day Massacre,” an angry white guy with tie askew was ranting in French. “We cannot allow our streets to become the Wild West as the Americans do. And even when one terrorist kills others, worthy of death though these victims were, they were still victims of a monstrous crime. And it was still an act of terrorism, by a fugitive sheltered in the hellish underworld beneath our sacred city!”

“You want me to kill the loudmouth?” Candace asked. “I mean, I can see why, but all respect to you, Mama, that’s not the sort of job I—”

“You misunderstand.” As before, Candace had started ignoring the Speaker, and heeding the one who Spoke. “As you might gather from his overheated rhetoric, your brother’s actions have made a marked impression. Especially on the authorities.”

“Oh, shit,” Candace said.

“Yes. Though details of the agreement with us have been covered up as a matter of routine, it’s been leaked that the Mayor and the President agreed to give Evernight a reprieve on the grounds they prevent a wanted terrorist from striking again. They have been deeply humiliated. And they react as powerful men who have been humiliated have the power to do.”

“The deal’s off.”

“More than that. Much more. Our watchers have seen an armored van leave the building in the 1st arrondissement that Section 23 of GIGN uses as its headquarters. It is rolling for the Pont Neuf that crosses the Seine to the Left Bank.”

“That evil bastard DuQuesne got his green light,” Candace said, sick and angry. Marcel, Marcel, what did you even think you were doing?

The slim fibril whipping out of nowhere to wrap Candace’s left wrist was so unexpected she almost tripped and fell face-first in the nasty-smelling water that ran ankle-deep in this stretch of the old Paris mining tunnels that made up most of Evernight.

They’ve found my commune beneath the Moulin Rouge. The words sang in her blood with the urgency of adrenaline. You must hurry. They’re wearing masks, and spraying gas from canisters.

“Shit.” Alarm thrilled through her, even more jangling than Mama’s neural intrusion. “Mama, you’ve got to pull your fibrils back down the tunnel away from there. Now.”

I can’t! My people need me. They’re falling down already. The poor innocents! I hope it’s only knockout gas.

“It’s not. It’s nerve gas, Mama. Pull back!” Talking out loud at a dead run was taxing her wind, but fear and anger helped keep her moving.

Surely they’d never do—

“You never met DuQuesne. This is exactly what he’d do. I’m surprised he didn’t just plug up the known entrances and flood the whole tunnel network with the shit.” Except they’d never plug all the cracks and holes, if they had a decade to try, she thought. Apparently even La Vipère had some scruples when it came to killing straight Parisian citizens and tourists in droves. Or his superiors did.

My senses there are growing fuzzy, her blood keened.

“Fuck. This isn’t an attack on your colony. It’s an attack on you. Pull your fibrils back now, a quarter kilometer at least or more if you can! It should take a while for the neurotoxins to travel up them.” I hope.

I can’t abandon my children!

“They’re already dead. Think of the rest of Evernight!”

But Candace knew as she spoke that breath was wasted. She was already whipping out her knife to slash through the tendril that had stayed stubbornly twined about her wrist for the last thirty meters. It gave a bit, like rubber tubing, but parted.

She stopped, knelt. The main skein of Mama’s fibrils ran along the base of the wall, just above the water. She grabbed it with her left hand. It was surprisingly heavy. Candace wondered just how many rats and ODing drifters Mama had had to metabolize to make so many kilometers of the stuff.

Mama read her intent. The cords of slimy tissue suddenly blazed her hand, like a live wire, like fire. Worse than the agony of La Vipère’s bite. She screamed—then hacked through the bundle with a single stroke.

“I hope you like my way better than being dead,” she said aloud, panting from exertion and the throbbing torment in her left hand. I also hope my way works.

She’d already begun to sprint, out of reach of Mama’s intact and wrathful tendrils. She opened her mouth, and Darkness poured out, to fill the tunnel network before her.

The rake-gaunt nat woman’s hysterical shrieks of terror went silent when Candace touched her eyes. “I can see,” she said wonderingly. Candace could barely hear her over the strangled squalling of the infant who had apparently been nursing when the Dark came upon them and stole away their sight.

She looked at Candace with wide pale eyes—Candace saw no colors in her Dark. “I can see!”

“Yeah. Now lighten up your grip on the baby. The baby can’t breathe.” The woman recoiled from her. “Now. Or I’ll have to break your arm.”

That snapped the woman out of it. She switched her constrictor clutch on her child to a gently fervent hugging and rocking.

Candace seized the hand of a wizened old man nearby, who looked as if all that was keeping him upright was the dark beetle carapace that covered his torso and legs, and pressed it against the woman’s arm. Stunned by his sudden, unexplained blindness, he didn’t resist.

Candace had hit a nest of maybe twenty Evernighters, all of them as sightless as if their eyes had been gouged out, none of them handling it much better than the nursing mother had been. Candace knew she’d never have time to touch everybody’s eyes and let them see through her Darkness. She felt bad about literally poking the first woman’s eyeballs, but she was the first at hand and there was no getting through her panic to get her to close her eyes.

“Take his hand. Good. Now lead the way back down the tunnel toward Mama Evernight, quickly as you can. The rest of you, come to my voice. Join hands, and form a chain.”

“Why should we?” somebody asked.