In Episode 9 of After Trek, the roundtable talk show that airs after Star Trek: Discovery, Executive Producer Aaron Harberts said, “Everything we do on Star Trek comes out of character, and also as much as we can ground in science, so, shameless plug: get [the real-life mycelium expert and scientist] Paul Stamets’ book Mycelium Running. Give it a read…[it] will give you very, very good hints as to what’s going to happen.” So I did.

I bought the book, which is essentially a textbook for growing and interacting with mycelium and mushrooms, and I read it. I’d say I read it so you don’t have to, but the truth is: it’s a brilliant work of science, and everyone should give it a shot, especially if you’re a layperson like me. In addition to learning how to grow mushrooms from my one-bedroom New York City apartment (which I am enthusiastically now doing, by the way), I also learned a ton about Star Trek: Discovery’s past, present, and possible future.

Much like mycelium branches out and connects varieties of plant life, I will use Mycelium Running to join Star Trek: Discovery to its underlying science. Fair warning: this post shall be spoiler-filled, for those of you who have yet to finish the first season of Star Trek: Discovery. As I alluded earlier, I am no scientist, and I welcome scientific corrections of any kind from those who have done more than buy a lone book and earn a “Gentleman’s D” in undergrad Biology years ago. Also, what follows are my observations and mine alone, and are not meant to represent confirmed links between Star Trek: Discovery and 21st century Stamets’ research. Finally, hereafter, “Paul Stamets” will refer to the real-life, 2018 Paul Stamets, unless otherwise noted.

All right, let’s talk about mycelium.

According to Paul Stamets, thin, cobweb-like mycelium “runs through virtually all habitats…unlocking nutritional sources stored in plants and other organisms, building soils” (Stamets 1). Mycelium fruits mushrooms. Mushrooms produce spores. Spores produce more mushrooms. If you’ve been watching Star Trek: Discovery, you probably stopped on the word “spores.” Spores are used as the “fuel” that drives the U.S.S. Discovery. But how?

In Paul Stamets’ TED Talk, we learn that mycelium converts cellulose into fungal sugars, which means ethanol. Ethanol can then be used as a fuel source. But that’s not what the spores do on the Discovery. There, they link the ship into an intergalactic mycelial network which can zap the vessel virtually anywhere they’ve plotted a course to. This could be considered a logical extrapolation from Paul Stamets’ work. As Stamets states in Mycelium Running, “I believe mycelium operates at a level of complexity that exceeds the computational powers of our most advanced supercomputers” (Stamets 7). From there, Stamets posits that mycelium could allow inter-species communication and data relay about the movements of organisms all around the planet. In other words, mycelium is nature’s Internet. Thus, it is not too far of a leap for sci-fi writers to suggest that a ship, properly built, could hitch a ride on that network and direct itself to a destination at a rate comparable to that of an email’s time between sender and recipient, regardless of distance. Both the U.S.S. Discovery’s and the Mirror Universe’s I.S.S. Charon’s spore technology demonstrate what this could possibly look like.

While these suppositions are theoretical by today’s standards, much has already been proven about mycelium, mushrooms, and their spores, and a great deal of that science could appear in future seasons of Star Trek: Discovery. From Stamets, we learn that mushrooms, developing out of mycelium, have great rehabilitative properties. They restore blighted land. In Stamets’ words, “…if a toxin contaminates a habitat, mushrooms often appear that not only tolerate the toxin, but also metabolize it as a nutrient or cause it to decompose” (Stamets 57). This means that, if an oil spill occurs on a piece of land, meticulous placement of mycelium could produce mushrooms there that would consume the spilled oil and convert the land into fertile ground. What’s more, the sprouting mushrooms could neutralize the toxicity of the oil by “digesting” it, meaning those mushrooms could be eaten with no ill effects felt by their consumers.

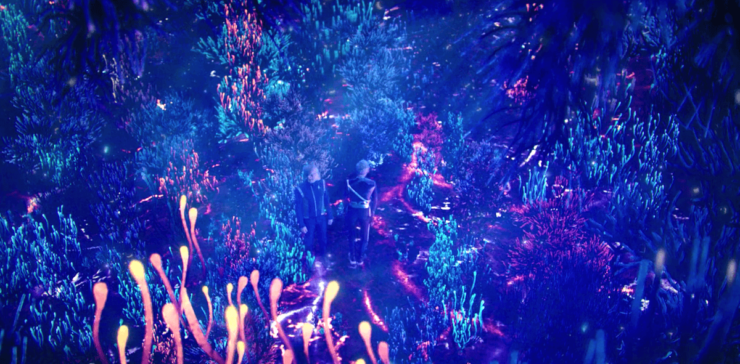

Star Trek: Discovery creates two opportunities for this science-based function to appear in Season 2. In the episodes “Vaulting Ambition” and “What’s Past Is Prologue,” we learn that Mirror Paul Stamets (Anthony Rapp) has infected the mycelial network with a disease or corruption that seems to be spreading. Scientifically speaking, the cure for this might just be more mycelium, which could consume the infection and revitalize growth in an act of bioremediation. This would create a “mycofilter” capable of restoring health (Stamets 68). Such a crop could already be growing on the planet the Discovery‘s Paul Stamets terraformed in “The War Without, The War Within.” As a brief aside, I was struck by the process Discovery’s Paul Stamets used to terraform that planet, specifically the rapid, powerful pulses applied to the planet’s surface after sporulation. This is wonderfully reminiscent of an old Japanese Shiitake mushroom-growing method called “soak and strike,” in which logs were immersed in water and then “violently hit…to induce fruiting,” pictured below (Stamets 141).

If one application of mycelium-based rehabilitation is the repair of the network itself, another possible use may be the healing of Mirror Lorca. While much speculation, currently, investigates the possible whereabouts of Prime Lorca, Paul Stamets has made me wonder if Star Trek‘s mycelium could repair a human body. It’s not that much of a sci-fi reach. A specific kind of fungus called “chaga” has been known to repair trees in just this way. Stamets writes, “When [Mycologist Jim Gouin] made a poultice of ground chaga and packed it into the lesions of infected chestnut trees, the wounds healed over and the trees recovered free of blight” (Stamets 33). Fungus, it is important to note, contains mycelium. Since Mirror Lorca fell into a reactor made of contained mycelium, one wonders if he didn’t integrate into the network, and, if so, if the network couldn’t act as chaga did on the aforementioned chestnut trees. This would take a great deal of incubation, perhaps, but there’s a possible host for that, too: Tilly. At the end of “What’s Past Is Prologue,” a single green dot of mycelium lands on Tilly and is absorbed into her. If this mycelium also contains the biological footprint of Mirror Lorca, his mycelial rehabilitation could be happening inside of her. Of course, one may desire such a restoration for Culber, but that seems far less likely as he (a) did not “die” by falling into mycelium and (b) seems to have died with enough closure for us to accept finality. But Stamets is quite clear about this: mushrooms are nature’s mediator between life and death. The implications this statement has for science fiction stories, especially Star Trek: Discovery, are vast. Indeed, these speculations are not directly linked to the science Stamets writes about, but they are exactly the sort of extensions science fiction writers might utilize to tell great Star Trek tales.

Given that mycelium is, as Stamets says, “a fusion between a stomach and a brain,” its roles in the Star Trek universe will surely be defined by “eating” (disease, death itself) or thinking (plotting courses, providing data) (Stamets 125). As mycelium works in nature, though, organisms are attracted to the products of its labor. Mushrooms draw myriad insects and animals who feast on insects. Therefore, the insertion of a (very large) tardigrade early on in Star Trek: Discovery‘s run makes sense. It potentially formed the same symbiotic relationship Earth’s organisms foster with mycelium and mushrooms: the insects receive nourishment, and, in some cases anyway, the insects assist with spore transport. This opens the door for Season 2 to explore more species that might be pulled toward the cosmic mycelial network seeking a similar relationship.

The better we understand mycelium, the better we understand the ethical questions posed by the spore drive. Mycelium is aware of the organisms that interact with it. Stamets notes in his TED Talk, that, when you step on mycelium in the forest, it reacts to your foot by slowly reaching up toward it. The largest organism in the world, Stamets suggests, may have been the 2,400-acre contiguous growth of mycelium that once existed in eastern Oregon (Stamets 49). If the future accepts mycelial networks as sentient, their use as forced ship-drivers could be seen as a form of abuse or, at worst, enslavement of an organism. This may help to explain why Starfleet ultimately abandons the spore drive. That, and the gnarly effects spore drive experimentation had on the crew of the U.S.S. Glenn in “Context Is For Kings.”

Star Trek is at its best when it’s fueled by a healthy blend of science and suspension of disbelief. When the foundational science is solid enough, we’re willing to take it a couple of steps further into the future, chasing a great sci-fi story. By reading Paul Stamets’ Mycelium Running, I learned some of the very real, fascinating science that spurred the writerly imagination we see materialize in Star Trek: Discovery—and, I have to say, I’m totally on board for it. This first season of Discovery not only succeeded in incorporating cutting-edge, 21st century science into its vision of the future, but seems to be building on that science in ways that could inform the show’s plot and character arcs, going forward. To quote Cadet Tilly talking to Rapp’s echo of today’s star mycologist, “You guys, this is so fucking cool.”

Note: all in-text citations came from Paul Stamets’ Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save The World from Ten Speed Press, copyright 2005.

Jonathan Alexandratos is a playwright and essayist whose work largely revolves around action figures and grief. The fungus that is Jonathan can be found @jalexan on Twitter.