Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

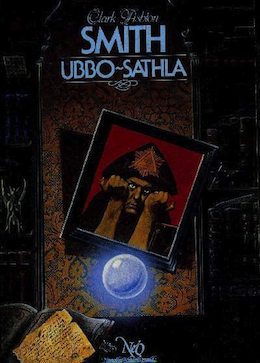

Today we’re looking at Clark Ashton Smith’s “Ubbo-Sathla,” first published in the July 1933 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

“Moment by moment, the flowing vision in the crystal became more definite and distinct, and the orb itself deepened till he grew giddy, as if he were peering from an insecure height into some never-fathomed abyss.”

Summary

The Book of Eibon supplies our epigraph: a description of Ubbo-Sathla, the featureless demiurge that dwelt upon Earth before even the Great Old Ones arrived. It spawned “the grey, formless efts…and the grisly prototypes of terrene life” which must one day return to it through the “great circle of time.”

A few years along that great circle, 1932 London to be precise, Paul Tregardis is idling in a curio shop. A dull glimmering draws his eye to a cloudy crystalline orb with flattened ends, pulsing light from its heart. Though he’s never seen anything like it, it seems familiar. The proprietor knows little of the crystal’s provenance, except that a geologist dug it out of a glacier in Greenland, in the Miocene strata. Perhaps it belonged to some sorcerer of Thule; no doubt a man could see strange visions if he looked into it long enough.

The crystal’s connection to Greenland—Thule—startles Tregardis. He has a medieval French copy of the fabulously rare Book of Eibon, which he’s found to correspond in many ways to Alhazred’s Necronomicon. Eibon mentions the wizard Zon Mezzamalech of Mhu Thulan, who owned a cloudy crystal. Could this piece, consigned to a table of dusty knickknacks, possibly be a wizard’s treasured scrying-globe?

Oh well, the price is moderate. He buys the thing.

Back in his apartment, Tregardis looks up Zon Mezzamalech in his vermiculated (!) Eibon. Sure enough, the mighty wizard had an orb in which he “could behold many visions of the terrene past, even to the Earth’s beginning, when Ubbo-Sathla, the unbegotten source, lay vast and swollen and yeasty amid the vaporing slime.” Too bad Zon left few notes on what he saw, probably because he vanished mysteriously soon after. The crystal itself was lost.

Again phantom memory tantalizes Tregardis. He sits at his writing table, the crystal before him, and stares into its nebulous depths. Soon there steals upon him “a sense of dreamlike duality”—he’s both Paul and Zon Mezzamalech, both in his apartment and in an mammoth-ivory-paneled chamber surrounded by books and magic paraphernalia. In the crystal, he—they—watch a swirl of scenes like “bubbles of a millrace…lightening and darkening as with the passage of days and nights in some weirdly accelerated stream of time.”

Zon Mezzamalech forgets Tregardis, forgets himself, until “like one who has nearly fallen from a precipice,” he pulls himself from this “pageant of all past days.” He returns to himself. Tregardis returns to the comparative dinginess of his London apartment, muddled and unclear about what just happened. He feels like “a lost shadow, a wandering echo of something long forgotten” and resolves not to look in the crystal again.

Yet the next day, he yields to an “unreasoning impulse” and stares into the misty orb again. Three times he repeats the experiment, to return “but doubtfully and dimly, like a failing wraith.” On the third day, Zon Mezzamalech overcomes his fear of falling into the vision of the past. He knows that potent gods visited the nascent Earth and left tablets of their lore in the primal mire, to be guarded by Ubbo-Sathla. Only by yielding to the crystal can he find them!

He (and Tregardis) disappear into a parade of unnumbered lives and deaths. At first they’re humans: warriors, children, kings, prophets, wizards, priests, women (apparently an entirely separate category from all these others). As time flows backwards, they become troglyodytes, barbarians, semi-apes. They “devolve” into animals: pterodactyls, ichthyosaurs, forgotten behemoths bellowing “uncouthly” at the moon. Things look up a bit when time flows back to the age of the serpent-people. They rewind through cities of black gneiss and venomous wars, astronomers and mystics. Then the serpent-people devolve into crawling things and the world becomes “a vast chaotic marsh, a sea of slime, without limit or horizon…that seethed with a blind writhing of amorphous vapors.”

It’s Earth’s birth, with Ubbo-Sathla at the grey center, sloughing off “in a slow, ceaseless wave, the amoebic forms that were the archetypes of Earthly life.” All around its formless bulk lie the tablets of wisdom left by the starry gods. There are none to read them, for Mezzamalech and Tregardis are now reduced to shapeless efts of the prime, who can but “crawl slugglishly and obliviously across the fallen tablets of the gods and fight and raven blindly among the other spawn of Ubbo-Sathla.”

Of Zon Mezzamalech and his disappearance, as we know, there’s the one brief mention in Eibon. Of Paul Tregardis and his disappearance, there are brief mentions in the London papers. No one seems to have known anything about him, and the crystal is gone, too.

Or at least, no one’s found it.

What’s Cyclopean: Antemundane, antenatal, antehuman! Really freaking long ago, is what he’s saying. Palaeogean, even.

The Degenerate Dutch: Of course all tiny magic macguffin shops must be run by Jews—in this case a “dwarfish Hebrew” distracted by Kaballah studies rather than the more mercenary variety. For bonus degeneracy, he’s also selling “an obscene fetich of black wood from the Niger.”

Mythos Making: Ubbo-Sathla is the first live thing on Earth—before Zhothaqqah or Yok-Zothoth or Kthulhut—it would call dibs on the planet if only it had the language to do so.

Libronomicon: This week’s dark fate can be blamed on The Book of Eibon, or a translation of a translation from the “prehistoric original written in the lost language of Hyperborea,” so basically everything here is Conan’s fault.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Magically induced amnesia is never a good sign. Not even “the sort of psychic muddlement that follows a debauch of hashish,” which seems like a hobby that would be both very distracting from sorcerous study, and possibly a necessary source of stress relief from the effects of same.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’m not sure this is, strictly speaking, a good story. It doesn’t exactly have a plot. It doesn’t do much that Lovecraft didn’t do earlier and better. But I’m a sucker for a good deep time rant and for overenthusiastic use of adjectives. These, Clark Ashton Smith provides with the cheerful exuberance of a squamous puppy, and here I am scritching the half-grown hound of Tindalos behind the ears and telling it it’s a good abomination, even though I suspect it probably isn’t.

Lovecraft’s deep time montages vary in quality themselves. They range from the masterful overview in “Shadow Out of Time” down to the random vampire visions of “He” and the ironic apocalypse of “Till a’ the Seas.” Frank Belknap Long’s “Hounds of Tindalos” offers a good rant on deep human history, but is humans all the way down to a dualistic Fall. Thinking of Long, I cheered at this week’s jump from humans to the reptile race from “The Nameless City.” (Or maybe just Silurians, it’s hard to tell.) Two sapient species isn’t enough to match Lovecraft’s spiraling cycle of species rising and falling into entropy, layer on layer of forgotten civilization, but it’s pointing in the right direction.

Of course Smith’s point isn’t the rise and fall of sapient species, but the unpleasantness of their origin. I suspect this is supposed to terrify in the same way as the protoShoggoth. Who really wants to think of our glorious panoply of life as growing out of amorphous slime—and can we really be all that glorious if our beginning was all gray and oozy and headless? I dunno. I guess my horror and loathing thresholds are set higher than most Weird Tales authors.

And then of course there are the much-desired tablets, and the ironically eft-ish Paul/Zon critter, no longer in a position to read them. My main reaction is that I really need a pamphlet on the Ubbo-Sathla hypothesis to hand out to creationists. Unintelligent design, maybe? Can you prove that the Earth wasn’t once an endless sea of protoplasmic slime? Without looking at the actual geological record, I mean. Obviously.

Poor Zon. Poor Paul. Especially poor Paul, who appears to be mind-controlled or just supplanted by the old sorceror. Maybe it’s an accidental side effect of the shared crystal, but more likely it’s some Curwen-esque attempt at forced reincarnation. Sorcerors are not known for going gently into that good night, after all. And they are known for setting up very-long-term plans that go bad at the last minute.

Wending back through the aeons to the twentieth century, I also feel unreasonably fond of the stereotyped Jewish shop owner who sells Paul the “somewhat flattened” knock-off trapezohedron in the first place. Perhaps it’s because his Yiddish accent is surprisingly un-sucky. Who knows? Nu? His shop is obviously full of plot hooks, but he just wants to study Kabbalah. It’s a living. Anyway, he beats the hell out of the villainous merchant in “The Mummy’s Foot.”

After I retire, I wouldn’t mind running a plot shop. It seems like a healthier lifestyle choice than buying anything from one.

Anne’s Commentary

By way of public service announcement, allow me to issue a caveat emptor to anyone who experiences an “aimless impulse” to go into a curio-dealer’s or antique shop or used bookstore, especially if that anyone nurses occult interests: Know that there’s nothing “aimless” about this kind of impulse. You are meant to find something in that shop, and it may very well ruin your day or even your run through this cycle of eternity. But not if you’re French. The Gallic immune system seems to produce antibodies against the deleterious effects of not-really-randomly acquired artifacts. Frenchmen have been known to impulse-buy an actual mummy’s foot with no more consequence than a pleasant date with a princess and a grand tour of the Egyptian Underworld.

At first “glance,” Paul Tregardis differs from the central characters in our last two stories of revelation found in that he’s not seeking a particular revelation — certainly not with their vigor, intensity and focus. Yet, though a mere “amateur” of anthropology and occult sciences, he owns just the fabulously rare grimoire that allows him to appreciate the significance of his lucky find: The Book of Eibon. Only in this book does Zon Mezzamalech and his cloudy crystal receive mention. Brief and casual mention, too, which it takes Tregardis a while to recall. What cinches his interest in the crystal is his inexplicable sense of familiarity, the way it tantalizes him like a lost dream — or memory.

We’re never told the exact relationship between Tregardis and Zon Mezzamalech, whether they are linked through the centuries by blood or spirit or some more obscure arcane energy. Whatever the linkage, it’s a strong one. When Tregardis gazes into the crystal, he first falls into a “duality” with the Hyperborean wizard — he is both, simultaneously. Then, “the process of re-identification became complete,” and he is Zon Mezzamalech. Finally, he knows what he’s looking for: the tablets of the antemundane gods, inscribed on ultra-stellar stone, no less! Shades of Mark Ebor, right? Except Mark Ebor only had to venture into the sands of the great desert, whereas Zon M. has to crystal-journey back in time to Ubbo-Sathla and the primal mire! Now there’s an epic quest, with more than psychological dangers attached. When Zon M. fears “falling bodily into the visionary world,” as into a precipice, that’s no metaphor. He does vanish. Tregardis does vanish. The crystal vanishes with them, the vehicle traveling along with its passengers.

And now, because Smith’s concept of Time is that it loops through a circle of (apparently) fixed events, the terrible irony of our pair’s situation is endlessly reinflicted They must struggle through the trials of many lives, human and serpent-man and animal, to reach the tablets of the elder gods as the spawn of Ubbo-Sathla, mindless efts able to perceive the elder wisdom only as carven curves and dashes and dots that irritate their slimy bellies, meaningless vexations.

But enough about those feckless humans. Ubbo-Sathla Its Own Self deserves some attention, because Smith manages to make It sound both awesome and repulsive. For Ubbo-Sathla is the source and the end. Mmm, nice. Which dwelt in the steaming fens of newmade Earth. Um, eww? Spawning grey, formless efts and grisly prototypes of terrene life! Definitely eeewww, although I’ve loved the word eft since I first encountered it in Browning’s “Caliban Upon Setebos”:

Will sprawl, now that the heat of day is best,

Flat on his belly in the pit’s much mire,

With elbows wide, fists clenched to prop his chin.

And, while he kicks both feet in the cool slush,

And feels about his spine small eft-things course,

Run in and out each arm, and make him laugh…

The he above being Caliban, who’s fixing to monologue about his witch-mom’s god of choice, Setebos. I think Caliban sounds a lot like Ubbo-Sathla, don’t you? What with the mire-sprawling and shedding of efts. Though Caliban has members and can laugh, hence has a mouth, hence has a head. Do the specialized body parts and ability to laugh make him superior to the “idiot” demiurge? Or does his addiction to monologuing, especially on theological points, plunge Caliban back below Ubbo-Sathla on the duh-scale?

Sometimes I lie awake long into the night debating such questions with the dark.

The dark wants to know what the hell a demiurge is, a partial compulsion?

Ah, darkness, my old friend, what a joker you are. Shall we go on to how Ubbo-Sathla can be “the unbegotten source” and how, regardless, that’s a great epithet? Also how the following description ranks among the all-time best Mythosian gross-outs: “[Ubbo-Sathla] lay vast and swollen and yeasty amid the vaporing slime.” Like bread dough left out to rise way WAY too long.

Dawn comes too soon. We’ll have to leave some riddles for another day, like is Ubbo-Sathla the protoshoggoth the Elder Things dread? Like, who are the antemundane gods who decide U-S would be the best librarian for their wisdom? Like, does every planet get its own mini-Azathoth/Shub-Niggurath hybrid to kick-start the flora and fauna?

In which case, it would of course be Nyarlathotep delivering the seed-Ubbos to each planet and smiling cryptic smiles at the thought of how many sorcerers that planet would later breed who’d reduce themselves to the equivalent of juvenile newts in an attempt to plumb the secrets of the ultra-stellar stone tablets Nyarlathotep was scattering about, each bearing choice laundry lists of the Outer Gods. Meaning most of the tablets were blank, for All Gods save the Soul and Messenger Himself went Full Commando.

Next week, a story of faith lost and—perhaps unfortunately—found, in John Connolly’s “Mr. Pettinger’s Daemon.” You can find it in his Nocturnes collection or listen for free here.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.