In Which Fëanor Goes All Fey, Balrogs Open A Can of Whoop-Ass, and the Oath Gets Well and Truly Underway As the Noldor Reintroduce Themselves to Middle-earth

With the Sindar kingdom of Doriath now established in Beleriand and fenced by the power of Queen Melian, and with Morgoth having stuck himself where the Sun don’t shine, we hit Rewind once again. In this, the thirteenth chapter of the Quenta Silmarillion, “Of the Return of the Noldor,” we go back to the last days just before the first rising of the Moon and the Sun. We also return to Fëanor, who’s got Noldorin boots on the ground in Middle-earth. With him are his sons, his troop of loyalists, and his burning quest of vengeance to achieve. What could possibly go wrong?

This is another very rich chapter and there is a lot of ground to cover. We’ve got Balrog bullies, Orcs galore, maimings, prophetic dreams, Dwarven excavations, and Elf-politics to address. Not to mention Arda’s biggest bird and…its very first dragon!

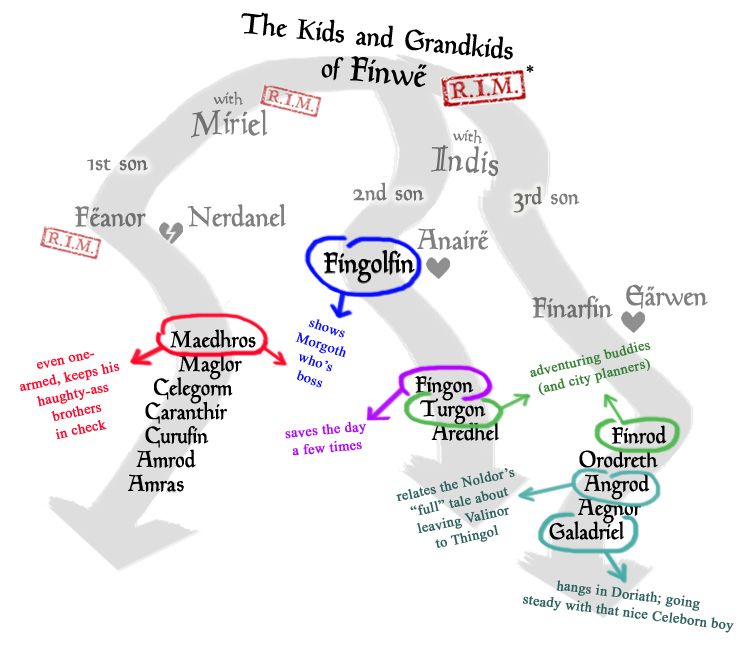

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Fëanor – Noldo, desperado, historical arsonist

- Maedhros – Noldo, eldest son of Fëanor

- Fingolfin – Noldo, the Elf who would be king

- Fingon – Noldo, valiant son of Fingolfin, harpist adventurer

- Thingol – Sinda, cagey king

- Ulmo – Vala, meddlesome Lord of the Waters

- Finrod – Noldo, cave-dweller

- Turgon – Noldo, city planner

Of the Return of the Noldor

In the land called Lammoth, the Great Echo, which was named after Morgoth’s rage-filled, Ungoliant-inspired cry, you can’t really be too quiet. Even Elves need to watch it. The acoustics are extraordinary. Sound travels: footfalls, voices, candy wrappers, and even the sound of the unjustifiable burning of a small fleet of masterwork Teleri ships in a vile act of treachery. And not only does the Noldor prince Fingolfin spot the flames of his half-brother’s betrayal from far across the strait between Aman and Middle-earth….so do Morgoth’s sharp-eyed Orcs! And they’re much closer.

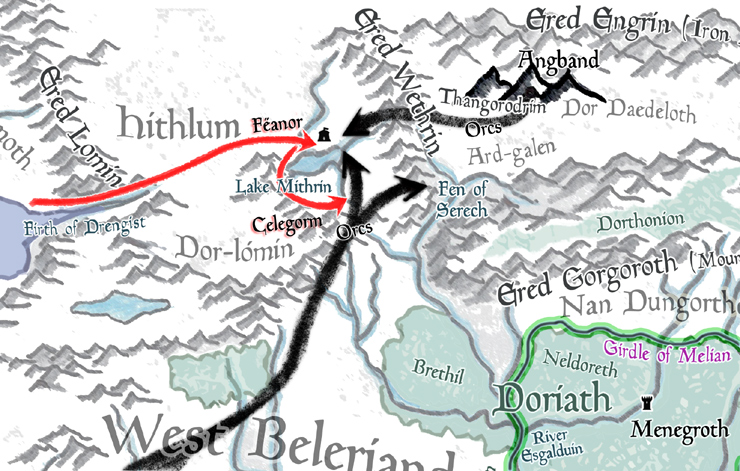

Soon after, Fëanor leads his considerably smaller host of Elves eastward and upward into the land of Hithlum (“Land of Mists”) and sets up an encampment on the north side of the lake called Mithrim. Before they’ve even settled in, out spills an army of Orcs, issuing from passes in Ered Wethrin, aka the Mountains of Shadow. This is Morgoth thinking it’s best to nip this potential Noldor problem in the bud. They’ve only just arrived on Middle-earth; surely this is the best time to squash them before they have a chance to spread out and put down roots!

But, ahh, Morgoth is forgetting where they’re newly arrived from: Valinor, Aman, and a fresh memory of the Two Trees, the light of which is “not yet dimmed in their eyes.” The Noldor—the best-armed Calaquendi in existence—are actually at the top of their game. Heck, no Elves in the history of Arda are probably more on top of their game than the exiled Noldor, truly superheroes among Eldar. And Fëanor is jacked up with purpose and a thirst for vengeance, to boot.

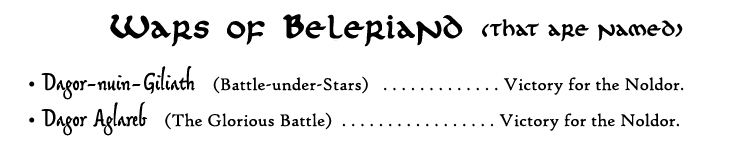

Now, this marks the Second Battle among the Wars of Beleriand. FYI, battles are going to become a continuing theme in Middle-earth in the First Age from this point on, so through the Elves and their boundless nomenclature,Tolkien gives these conflicts some pretty sweet names.

This one is called Dagor-nuin-Giliath, which means Battle-under-Stars, as it’s the last one taking place before daytime becomes a thing. And in this conflict, Fëanor and his loyalists make short work of the Orcs despite being outnumbered and even caught off guard. What the hell even are these Orcs, anyway? The Noldor would not have seen their like before now! But you know what? They’re violent, they’re uncouth, and seriously unlovely. They’re clearly Morgoth’s minions, and so need slicing up.

The Noldor get to work with their “long and terrible” swords, mowing down the Orcs before giving chase onto the plains of Ard-galen, aka Morgoth’s very big front lawn. And Fëanor’s son Celegorm leads a portion of Fëanor’s army in an ambush maneuver, crushing a second wave of Orcs who come running up from the south—Orcs who’d been bothering poor Círdan the Shipwright and the other Sindar down by the western shores.

Morgoth’s forces are totally wrecked, and all that remains is likened to a “handful of leaves.” This has to be giving the Dark Lord pause. Like, maybe poking the Noldorin hornet’s nest hadn’t been such a great idea. But the swift victory makes Fëanor cocky. (Well, even more cocky.) He can taste victory! Is this all Morgoth’s got? Fëanor might have come to Middle-earth expecting a long campaign against his foe before finally throwing him down and prying the Silmarils out of Morgoth’s murderous hands—but suddenly the path seems clear right now. Why not run on to where the Orcs had been fleeing, where their master surely dwells under those mountains? So he boldly goes where no Elf has gone before.

Alas, Fëanor knows nothing of Angband—how could he, he only just got here!—nor of all the renovations and monster-making Morgoth’s been working on. But…

even had he known it would not have deterred him, for he was fey, consumed by the flame of his own wrath.

There’s that recurring fire theme that we see throughout Fëanor’s life. All the talent that Fëanor exudes by merely being—talents for crafting, for subtly, for artistry, and now for war—is burning him up fast, driving his choices into a trajectory of madness. Every means, to him, is justified by the end, and the end lies before him: Morgoth is near, and so are the Silmarils. Fëanor thinks he can achieve the demands of his famous Oath right now. Why wait? Strike while the iron is hot, and all that, right?

But Fëanor’s crazy train has long since gone off its rails. So without waiting for his sons and other reinforcements to show up, he hurries on with only a few friends. He crosses right into Morgoth’s domain of Dor Daedeloth and, surprise, the Dark Lord himself is a no-show. Why should Morgoth do the dirty work when he can just send out the Balrog Brigade? Fëanor’s never met them before; hell, he may never even have heard of them.

But to Fëanor’s credit, it takes a whole team of Balrogs to take him down.

Tragically, in Tolkien’s legendarium, the most epic of contests are assigned the fewest of words. And it’s no different for the final stand of Fëanor. Surrounded by the fiery, whip-wielding demons of terror—the Valaraukar, the scourges of fire—even the intrepid Fëanor cannot stand indefinitely. He is but one Child of Ilúvatar and they are a whole crew of fallen Maiar. Interestingly, we’re given the name of their boss where the narrator hadn’t mentioned it before: Gothmog! That word is actually used once in The Lord of the Rings, where it is the name of a lieutenant of Sauron’s in the siege of Gondor. He might be an Orc or a Man, it’s not made clear, but that guy’s namesake is the goddamned Lord of Balrogs. Yeesh.

“Spoiler” Alert: This original Gothmog is introduced like some sort of celebrity we’ve already heard about, because as he’s named Tolkien wastes no time in forecasting his demise, even as he name-drops someone else. So we’re to understand that Gothmog will one day be slain—to whatever extent a Maia can be extinguished in physical form—at the hands of an Elf named Ecthelion, and in a city not even built yet! Okay, got it! Meanwhile, back to the action….

So it’s Gothmog, Lord of Balrogs, who delivers the “mortal” blow to Fëanor, striking him down with grievous wounds. But of course it’s Fëanor’s own reckless and overwhelming confidence that really defeated him. He was called “fey,” and to be fey is to be doomed to die, which is kind of what he’d been ever since stranding Fingolfin’s crew on the far side of the Helcaraxë. And fey is what he was the moment he decided not to hold up for just one damned second and let his own people catch up. Or, better still, maybe wait for Fingolfin and his much larger host to arrive.

But no. Once again, Mandos had called it. In the last chapter the Doomsman of the Valar said:

To me shall Fëanor come soon.

And so he shall.

Gothmog and the Balrogs don’t get their chance to actually tear Fëanor apart, though. His sons swoop in just in time to drive the mighty demons off. And they carry him in retreat back to the mountains, but only get as far as the climb up before Fëanor finally throws in the towel.

And what a fiery, thrice-cursed, pride-soaked towel it is. From their vantage in the pass, the dying Fëanor at last gets a clear view of the volcanic peaks of Thangorodrim in the distance…

and knew with the foreknowledge of death that no power of the Noldor would ever overthrow them; but he cursed the name of Morgoth thrice, and laid it upon his sons to hold to their oath, and to avenge their father.

Fëanor is a piece of work among pieces of work. In life and death, he’s the most influential Elf there’ll ever be. His pride and wrath ripped an entire kindred of Elves (all but that 10%) out of paradise, got them all yelled at, and ran them painfully through a gauntlet of blood and ice; and now he’s checking out. He doesn’t have to see the rest of it through personally. Or rather, doesn’t get to. And worse, knowing that even the entirety of the Noldor cannot defeat Morgoth, out of sheer pride he condemns his own kids to the vain pursuit of their Oath. The Oath that will claim their lives. As the Prophecy had warned, “yet slain ye may be, and slain ye shall be…”

Fëanor is effectively thinking, “You can’t win, dear sons, but go ahead and suffer and toil over it anyway, even as it divides you—because I refuse to apologize or even just admit that I was wrong.” Fëanor’s doubling down in sin is Morgoth’s greater victory, more so than the Elf’s actual slaying. Morgoth didn’t even need to show up for that. Thus is consigned the legacy of Fëanor, a great Elf, a master crafter, a tenacious warrior. But not a great dad.

Then he died; but he had neither burial nor tomb, for so fiery was his spirit that as it sped his body fell to ash, and was borne away like smoke; and his likeness has never again appeared in Arda, neither has his spirit left the halls of Mandos. Thus ended the mightiest of the Noldor, of whose deeds came both their greatest renown and their most grievous woe.

The narrator is presumably speaking in the present, which could be the Fourth Age for all we know. So while Elven spirits wait in the Halls of Mandos for a time and might be rebodied, we’re told straight-up that Fëanor is still there. I wonder if he gets to speak with his father, or mingle with anyone else he’s wronged. What of his mother, Míriel?

And yet, it kind of seems for the best. Even if Fëanor had survived the Balrogs, and was miraculously willing to be more strategic in handling Morgoth, would he really have played nice with the Sindar of Beleriand? (No.) Would he voluntarily play second fiddle to Thingol and settle for some some corner realm? (Definitely not.) How would Mr. “No other race shall oust us!” have treated Men or Dwarves if he’d met them? I shudder to think. The answer, of course, is to simply look at what his sons do in his absence and imagine how much more extreme their dad would have been.

Speaking of… Within the very hour of Fëanor’s self-immolation, before there is time for his sons to mourn or curse their fate, emissaries of Morgoth show up and speak of surrender to them. Will the Noldor come and discuss? They even dangle a shiny carrot to entice the Elves—the return of exactly one Silmaril. Simply refusing the emissaries isn’t an option. All seven sons have sworn to “pursue with vengeance and hatred to the ends of the World,” and the Silmarils are really close.

Maedhros, eldest of Fëanor’s sons and chief heir, takes the bait. Now, he knows it’s a trap, knows Morgoth is a lying bastard who can’t possibly mean any of this. So even his acceptance is a strategic play. Maedhros convinces his brothers to play along and then he goes with a strong company of Elves to the meet-up, thinking to overwhelm Morgoth’s crew with sheer force of arms. But, well, Morgoth already has the home-field advantage—this is all happening on his doorstep—and of course he sends Balrogs. It’s no competition.

Maedhros’s company is wiped out but he is taken alive back to Angband. Morgoth tries the hostage thing, demanding the Noldor all back off. But for all the folly of their Oath, it does make the sons of Fëanor stubborn even in the face of torment and war…or at least it does for now, when they’re all gathered together. The Oath means they won’t negotiate with Morgoth, not even at the cost of Maedhros’s freedom. (And to be fair, Maedhros probably wouldn’t have negotiated, either.) Morgoth took, held, and kept all three Silmarils, after all—so he’s numero uno on their hit list.

Realizing the brothers are not going to cave, Morgoth just sticks the Elf to his mountain like a refrigerator magnet. Which is to say, he hangs Maedhros by the wrist on a band of steel, hammering it into the face of a precipice of Thangorodrim. Up amid the fumes and stink, Maedhros languishes in torment, hanging by one arm. And like all Elves “new-come from the Blessed Realm,” this Calaquendë can endure a lot, and for a long time. Yet none of his brothers know where he is. For all they know, he might be chained to Morgoth’s own throne in the depths of Angband. They don’t know he’s dangling from a high precipice. So things are looking rather dark for him.

But they’re not so dark for the world at large! Just as Fingolfin arrives on Middle-earth some time later, the Moon soars up into the sky, amazing everyone. But it’s when he and his host of Noldor reach Mithrim several days later that the Daystar—the Sun!—rises from the West and bathes Middle-earth in its overarching light. Vibrant life is triggered throughout the world, and flowers spring up from the seeds left long ago by Yavanna as though Fingolfin’s own feet were the catalyst for growth. Talk about an entrance! These are the reinforcements that Fëanor should have waited for.

But there will be no living reunion for Fingolfin and his half-brother. Fëanor is already gone. Well, the Noldor prince leads his army—still fresh from the hardships of the Helcaraxë, by the way—right on through the Mountains of Shadow into the plains of Ard-galen, and then right up to the gates of Angband. Fleeing the flaming light of the Sun, Morgoth’s forces make themselves scarce. They hide in their caves and dungeons like a bunch of fraidy cats, unwilling to face this angry army of High Elves. Fingolfin bangs on the doors and the Noldor blow their trumpets, issuing their challenge. But unlike a certain someone, Fingolfin’s not so reckless. He takes it all in, sees Angband’s formidable gates by the literal light of day, and knows that laying siege to it directly would be useless. While Morgoth hunkers down like this, there’s no breaking in. The best the Noldor can do is try to keep Morgoth holed up, hopefully for good.

So Fingoflin withdraws and settles in on the north shores of Lake Mithrim. The sons of Fëanor—well, minus Maedhros, who’s been left high and dry—take their leave and settle on the southern shores with their much smaller group of loyal followers. Now the lake, and of course more tension than an Orkish snare drum, divides them. Things are awkward. Can they continue avoiding the Helcaraxë-and-ship-burning-shaped elephant in the room? Meanwhile, from the safety of his dungeons, Morgoth laughs at the poison—that he himself first disseminated among them—still doing its work on the Noldor. Maybe he doesn’t need to destroy Ilúvatar’s precious Children. Maybe the Eldar will do it to themselves.

Just for good measure, Morgoth yanks on whatever pull-chain makes the stacks of Thangorodrim belch out their smoke. Clouds of foulness from the bowels of Angband go drifting westward to settle and eddy around the Noldor, darkening their camps and generally communicating Morgoth’s middle finger to them all. “I can’t come out right now,” he seems to be saying, “but hey, smell this.”

But then something unexpected happens. Fingon, Fingolfin’s eldest son, steps up in a big way. Deciding he wants “to heal the feud that divided the Noldor,” he goes on a solo quest. See, long ago, back before the flight of the Noldor, before the Oath, before the Darkening of Valinor, and before “lies came between them” thanks to then-Melkor, Fingon and Maedhros were really good friends. Despite their dads’ hangups, they got along great. And now the mere memory of that time creates a burning need in Fingon to find his friend again—even as Maedhros’s own brothers seem to have given him up. Even more striking: Fingon doesn’t know that Maedhros had spoken up on his behalf before the burning of the Teleri ships. He’d tried to get his dad to turn back and bear “Fingon the valiant” across the strait first. Fëanor, of course, didn’t cave on that. But as far as Fingon knows, Maedhros never even looked back.

Without telling anyone, Fingon sets out under Morgoth’s concealing stink-clouds. He’s on a one-Elf mission to find and rescue his old chum from the depths of Angband itself. Perhaps one stealthy Noldo can succeed where a trumpet-blasting army cannot. When he gets to the hellish fortress he finds no Orcs or demons out and about—they’re all still cowering from the daylight, much dimmer though it must be around there—yet he can’t find a way in. So Fingon wanders around Thangorodrim’s exterior, hiking, climbing, exploring…and finally despairing. But then he pulls out his secret weapon, a thing so awesome that no power in Dor Daedeloth can possibly contend with it. That’s right, despite the near presence of a horde of Orcs and monsters, Fingon breaks out his…harp! Because he’s an Elf, goddammit, and in Tolkien’s world, an Elf is as badass with a musical instrument as with a sword. So…

he took his harp and sang a song of Valinor that the Noldor made of old, before strife was born among the sons of Finwë; and his voice rang in the mournful hollows that had never heard before aught save cries of fear and woe.

This isn’t strategy. It’s defiance. It’s heartfelt expression. And yet Maedhros in his anguish hears it, and he takes up the song, too. He knows it! Why? Because this is a tune from better days long ago. This was probably a song they played together whenever they jammed in their garage band back in Tilion. So not only are we going to see that Elves sometimes use music to solve problems in other parts of the book, but the very idea of song-based searching for friends is a recurring plot device in Tolkien’s work: Think Sam and Frodo in Cirith Ungol. And we’ll see it again in Lúthien’s tale.

Well, once Fingon locates his friend, the situation is still dire. He cannot physically reach him on the sheer face of the cliff wall, and he can see that Maedhros is in torment. Maedhros begs for death, for a mercy killing in the form of a well-placed arrow. Fingon has a hard choice, but sees no other course. He can’t just leave Maedhros in anguish, yet he can’t free him, either. So Fingon nocks an arrow and calls out a prayer to Manwë, “to whom all birds are dear,” asking for a clean shot with the feathered shaft. Despite having heard Mandos’s Prophecy, knowing that even the “echo” of the Noldor’s “lamentations” will not pass over the mountains to Valinor, he hopes yet for some pity. Creak goes the bowstring…

But ahh, the King of the Valar has already been following the situation, because of course he has. The Valar care deeply, and we learn it immediately when Manwë’s special ops answer the call. Why are they close enough to even help? Because his Eagles have already been dwelling in aeries and crags around the North in order to keep tabs on Morgoth. But note that Manwë gets involved, and indirectly, only as a response to Fingon’s honest prayer. He could surely have sent one of his birds to the Noldor sooner, and told them exactly where to find Maedhros. But that’s not how this all works.

In all the days, months, or possibly years that Maedhros has been hanging in torment on the mountain face, could he have called out to the Valar for help? If not to Manwë, maybe to Varda, who is most loved by the Elves? Maybe, but probably not. This is Fëanor’s eldest son, and he knows where he and his father and brothers stand in the eyes of the Valar. Especially that Mandos, who sure gave them all the stink eye back in Aman. “Slain ye may be, and slain ye shall be” they’ve been told. Maedhros clearly expects to die, anyway.

But it’s Fingon the valiant who takes the risk. This is usually how eucatastrophe (“a sudden and favorable resolution of events”) works in Tolkien’s legendarium. The Eagles won’t just show up and save the day out of nowhere. But stick your neck out first, go at least eight of the whole nine yards, and if you’re doing the right thing, hey, a little bird might just help you out.

And, well, it’s not just any bird that shows up this time.

Now, even as Fingon bent his bow, there flew down from the high airs Thorondor, King of Eagles, mightiest of all birds that have ever been, whose outstretched wings spanned thirty fathoms; and staying Fingon’s hand he took him up, and bore him to the face of the rock where Maedhros hung.

The first thing worth asking is, how wide is thirty fathoms? That’s 60 yards or 180 feet. That’s as wide as the Leaning Tower of Pisa is tall. Thorondor is a big damned bird. He’s at least twenty-four times the size of a real life bald eagle (which can have a wingspan of up to 7.5 feet).

Fingon has to know that Manwë has indeed reserved some pity for the Noldor. But Thorondor is just the ride. And when he reaches Maedhros, there’s no breaking the “hell-wrought” iron manacle that Morgoth bound him with, it’s way too strong. Again, the eldest son of Fëanor figures his time is up and just begs his friend to finish him off. But no way, Josë! A day may come when Maedhros has to take the ultimate dive and accept the end that his father’s Oath has made inevitable—but it is not this day, here on the face of Thangorodrim! Manwë just sent the freakin’ King of Eagles.

So Fingon does what every good friend and wingman would do when his bestie is stuck between Morgoth and a hard place: he cuts off the dude’s hand with his sword. Maedhros and his bleeding arm are thus freed from bondage, and Thorondor bears both Elves away and back to the safety of Lake Mithrim.

If you’re Calaquendi and the light of Aman is not yet dimmed in your eyes, whatever doesn’t kill you absolutely makes you stronger. And Maedhros is a prime example. He heals up and becomes all the more wrathful against Morgoth—and is even more deadly as a lefty!—and he is wiser for the ordeal. Fingon the valiant came through for him. What a guy. Everyone rallies around and praises Fingon, while Maedhros begs forgiveness for ditching them back in Aman. Maedhros is willing to be the bigger Elf (more so than his little brothers) and works to ease the tensions between the house of Fëanor and the house of Fingolfin going forward. Moreover—and this is huge—Maedhros even renounces the kingship which technically would have come to him as the eldest heir of the eldest son of Finwë. He says to Fingolfin, his uncle:

If there lay no grievance between us, lord, still the kingship would rightly come to you, the eldest here of the house of Finwë, and not the least wise.

So Fingolfin will be the King of the Noldor. Now, not all of Fëanor’s sons are cool with this—not even close. But too bad for them, Maedhros is still the eldest and he wants there to be unity among the Noldor. There’s no evidence of this, but I’m thinking he might have employed the time-honored big brother stratagem known as why-are-you-hitting-yourself-why-are-you-hitting-yourself?! In any case, the house of Fëanor is now called the Dispossessed, and they’re going to be kings of a whole lotta nothing. Which doesn’t mean they’re not going to be arrogant lords bossing people around from time to time.

What follows in the second half of this chapter concerns the growing pains involved in the Noldor trying to settle into Beleriand. This is where Fëanor led them, after all, and they’re kind of stuck with it. There’s no going back to Valinor, even if they wanted to (as clearly many of them do). So it’s time to make the best of it and maybe, just maybe—if Fëanor wasn’t totally off the mark about everything—they can still find realms of their own. Such ideas were kindled in the hearts of its princes. Oh yes, and ladies: Galadriel is here with her brothers. She crossed the Helcaraxë, too, as part of her uncle’s host. This lady’s seen a lot of shit in her time, no less than they have.

And we can recall from four chapters ago that Galadriel was eager to be gone from Valinor, eager to come here to these “wide unguarded lands” and possibly govern a land of her own. (She does have a bit of a dominion bent, doesn’t she?) And you can bet her eyes are wide open now. But to her credit, the future Lady of the Galadhrim is in no hurry; clearly Beleriand isn’t entirely unguarded. She’ll do her homework first. And her brother Finrod is now the head of the house of Finarfin, since their mum and dad stayed in Valinor.

So now we come to the politics and a bit of the lingering strife of the Elves of Beleriand. Not to mention some more battles, as Morgoth tries to make trouble and test the strength of those accursed Children of Ilúvatar. He was doing just fine troubling the Sindar before Fëanor and Fingolfin and all these bright-eyed Calaquendi showed up.

By this time King Thingol is well aware of the return of the Noldor, and he “welcomed not with a full heart the coming of so many princes in might out of the West, eager for new realms.” But the Sindar, his people, are for the most part delighted to see their old friends again. They even assume, naïvely, that the Noldor must have been sent by the Valar to come help defeat Morgoth. (Yeah, that’s not how Mandos tells it….)

But as we’ll see, the Noldor are going to be, as a rule, very tight-lipped about the circumstances of their departure from Aman. Whenever that comes up, they keep it vague or change the subject. Impressively, the Kinslaying cat actually manages to stay in the bag for, like, several hundreds years! That can’t be easy.

But the reunion of the Noldor and the Sindar is mostly a glad one. The last time these former Teleri—that is, those who kept stalling and the ultimately decided not to take Ulmo’s ferry-island to Valinor—saw their Noldor friends was many thousands of years ago! And at first, there’s a bit of a language barrier to get past. You know, due to the “long severance” of “the tongues of the Calaquendi in Valinor and of the Moriquendi in Beleriand.” The Noldor speak Quenya while the Sindar are speaking Sindarin. The Noldor are quick to master and use the Sindarin tongue, so this is smoothed out before long.

Thingol is uneasy, though. The Noldor are here, but…where’s Finwë? These two were BFFs in the good old days of Cuiviénen. Remember way back then? They were so young! At this point, though, Thingol has a tendency to distrust all non-Sindar he hasn’t got family ties with. Which means the only ones with an open invitation to visit him in Doriath are the children of Finarfin (Finrod, Orodreth, Angrod, Aegnor, and Galadriel) because Finarfin had married Thingol’s own niece, Ëarwen. Who was, incidentally, called the Swan-maiden of…ahem, Alqualondë (you know, of the Kinslaying at Alqualondë).

Well, it’s Angrod who goes first. He sits with Thingol and tells him the full story of the Noldor’s journey from Valinor. Well, if by “full” we mean everything but the whole flight aspect of it, the Kinslaying or why it would even come up that Fëanor would want Teleri ships, and anything about an oath or a prophecy. And he definitely says nothing about Mandos hollering at them from a mountaintop or anything crazy like that. Still, Thingol accepts Angrod’s watered-down, omission-heavy account at face value, as he’s mostly interested in numbers, hierarchies, and all the Orc skirmishes up in the north. He’s a king who thinks about kingly things like dominions and rulership.

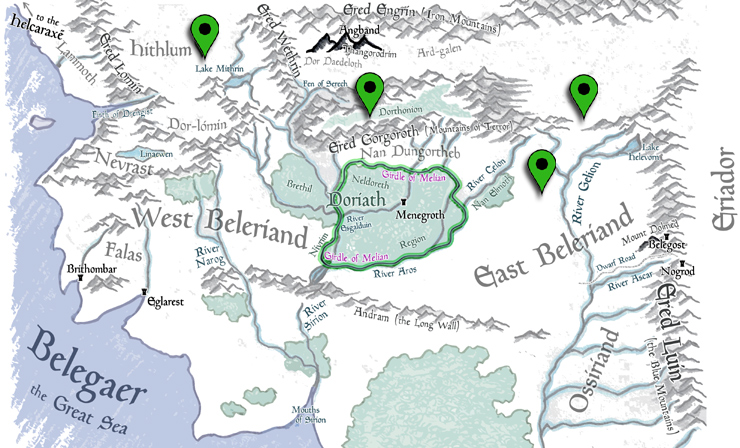

And so Angrod returns to the rest of the Noldor with a laundry list of places Thingol said they’re allowed to settle in—notably Hithlum, Dorthonion, and the “empty and wild” lands east of Doriath.

Fëanor’s sons are immediately pissed. Even the higher-minded Maedhros understands that Thingol is just handing out places he himself doesn’t already control. And that Thingol would obviously be glad to have non-Sindar occupy such regions just to serve as meat-shields between himself and Morgoth. Fingolfin and Finrod just accept it straight-up, though; they’re glad of any peace they can have and are more concerned at present with keeping an eye in Angband’s direction. Sharp-tongued Caranthir, the fourth son of Fëanor, starts trouble by questioning why it was Angrod who even went to meet with Thingol in the first place. To prevent further conflicts in the family, Maedhros reins in his brothers.

So the first to go and secure lands that they can slap their names on are the sons of Fëanor. Maedhros, as the most mature and selfless of them, actually accepts the wide open land to the east and north that has no natural barriers against Morgoth. This becomes the March of Maedhros, and the Elf thereby makes himself the first line of defense against their foe. But he also steers his brothers in this direction to keep them away from Fingolfin in order to “lessen the chances of strife.”

Meanwhile Caranthir settles into the valley around Lake Helevorn where he can set up trade with the Dwarves who traffic into Beleriand from their cities Nogrod and Belegost. Caranthir is no friend to the the Dwarves, as he can barely hide his “scorn for the unloveliness of the Naugrim,” but he’s an Elf with good business sense. He and the Dwarves find their common ground—crafting is one thing both Noldor and Naugrim are into—and thus they profit from one another. Plus they both hate Morgoth, so at least there’s that.

And now we span some time. Twenty years, an eyeblink to the Elves, go by as the Noldor settle into their respective pockets and corner realms. Fingolfin then has the temerity to host a big celebration and hope that Morgoth doesn’t crash it; he chooses a green and scenic spot where the River Narog comes together at the foot of Ered Wethrin, the Mountains of Shadow.

Now this is a Noldor-hosted (and, I assume, -catered) event, but all Elves are welcomed. Called the Feast of Reuniting, almost everyone who can attend does, from far and wide. All the important Noldor princes, lords, and ladies…minus five of the seven sons of Fëanor (big surprise). Green-elves and Gray-elves galore come, even Círdan and some of his Elves from the Havens. Only two members from Thingol’s court attend (meaning that the king and queen noticeably do not): Mablung and Daeron, chief captain and chief loremaster respectively. Both of these chaps will play roles in Lúthien’s tale several chapters from now. Suffice to say they’re both tight with Doriath’s royalty.

Awesomely, the feast goes off without a hitch. No Orc attacks, no angry words, nothing gets toppled. Friendships are renewed and oaths of loyalty are made as High Elves, Gray-elves, and Green-elves do what Elves do best: they talk, they tarry, they make merry. This is when the Noldor really start to learn and adopt the Sindarin language. Also, there’s no way the Moon and Sun and all the new varieties of plant life aren’t big conversation pieces. Not to mention all their different names for these things.

The Moon and Sun have only been swishing across the sky for some twenty years now; that’s nothing to Elves, many of whom were at Cuiviénen and are still accustomed to thousands of years of starlight only. Back in their day, there was none of this newfangled “daytime” that all the youngsters keep going on about. And gosh, it sure is a lot warmer than it used to be! What’s with the different phases of the Moon? And have you noticed we’ve got clouds now?

Another thirty years go by with still no problems from Morgoth’s corner of the world, aside from his passive aggressive brooding. Then one day, Turgon and Finrod, another pair of cousins who are good friends, go adventuring together along the River Sirion. Finrod, if you remember, was one of the more reluctant-to-leave-Valinor among the Noldor, and it was Turgon who lost his wife to the icy teeth of the Helcaraxë. It feels like their wanderings are perhaps a time for both to do some soul-searching in nature.

And so it’s probably not by chance that Ulmo, the busybodiest of the Valar (in a good way), chooses these two Elves to mess with (in a good way). We were explicitly told back in the Valaquenta that Ulmo “loves both Elves and Men, and never abandoned them, not even when they lay under the wrath of the Valar.” Valinor might have NOLDOR NOT ALLOWED signs hanging on its mountain-fence, but Manwë never forbade the Valar from coming over to Middle-earth. After all, we already know he’s still got his Eagle eyes in the sky.

Being one of the most learned of the Music of the Ainur, Ulmo has some insight into the troubles that Morgoth is going to bring, so his plan is to prompt both Turgon and Finrod to help guard against them. While the two are adventuring together, Ulmo slaps them both with “heavy dreams” one night when they’re passing through the Meres of Twilight—a lovely place where the rivers Aros and Siron meet.

These Ulmo-inspired dreams “trouble” the Elves but also fill their heads with ideas and thoughts for the future. They don’t discuss them, as each Elf thinks he might have been the sole recipient of such dreams.

Once they go their separate ways, Finrod travels with his little sis, Galadriel, to visit Doriath. He’s uber-impressed with the beauty—and more importantly, the defensibility—of the city Menegroth, the Thousand Caves. He even confides in his Telerin mom’s uncle, King Thingol, telling him about his secret dreams. Thingol obviously likes the young Elf, even if he is one of these upstart Noldor. (And frankly, who wouldn’t like Finrod?) He tells him about the deep gorge of the River Narog and the wooded highlands of that region, suggesting that those might be good places to poke around. Remember, Thingol was wandering and ruling Beleriand for a very long time. He’s been around. He knows all the best spots.

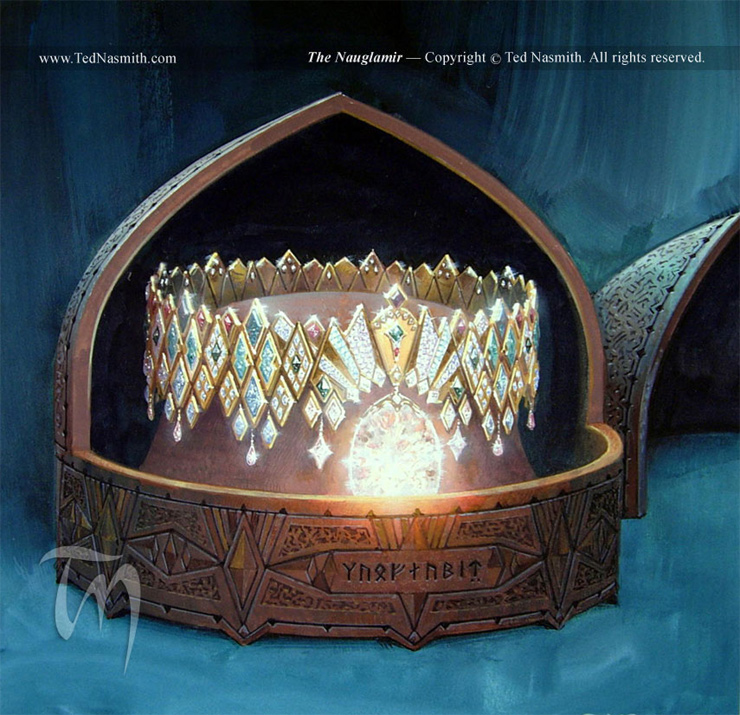

Not only does Finrod find and love the Caverns of Narog, he gets to work making a fortress out of it. I’m thinking he even has his Dwarven contractors recommended by Thingol, because it’s with the help of the Naugrim of the Blue Mountains that this new stronghold, Nargothrond, is carved—just as Menegroth had been. And Finrod pays well! He brought more gems from Valinor than any Noldor, which means he probably had heavy chests and coffers of jewels carried across the Helcaraxë by Elves of his father’s court. But knowing Finrod, he wouldn’t have just sat back and made his servants do all the heavy-lifting. Dude probably carried the heaviest ones himself.

Well, the Dwarves also become fond of Finrod, so much so that they even give him his own name in their language of Khuzdul (because Tolkien), which is a huge sign of their esteem for him. Whereas I assume the Dwarves come up with insulting, spoken-only-behind-the-back nicknames for all the haughty Elf-lords they’re use to working for, they instead call Finrod Felagund, Hewer of Caves. It’s freakin’ badass for Elf to have a Khuzdul epithet.

The Dwarves even craft for Felagund a necklace, or “carcanet,” of gold which is strewn with Valinorian gems. Called the Nauglamír, it’s the “most renowned of their works in the Elder Days,” and it’s being introduced to us now to foreshadow some actual drama later. In general, when a piece of jewelry gets named in Tolkien’s legendarium, you can bet someone’s going to fight over it sooner or later.

Now Galadriel chooses not to go and live in her brother’s realm because she’s loving it in Doriath. Also, she wants to stay and see about a boy, a nice Sindar chap named Celeborn (KEH-leh-born). You might have heard of him? He also happens to be related to the king. And now that Galadriel has met Melian, a straight-up Maia queen, well, she’s clearly found herself the perfect mentor. One who knows about ruling a forest realm, dispensing wisdom, and preserving beauty and power for as long as she can. All duties Galadriel would very much like to employ herself one day.

Turgon, meanwhile, doesn’t go quite as far as his cousin Finrod with establishing a new stronghold. Not yet. He returns to the coastal region of Nevrast where a bunch of the Noldor have settled, and he hangs out by the shoreline. There he pines for that great Noldorin city on a hill, Tirion, which now lies far across the Great Sea in a land he’s been banned from. Which sucks. Those were happier times; you know, back when he had a wife and that prick of an uncle, Fëanor, hadn’t wrecked everything yet.

Well this time, Ulmo just shows right up. The Lord of Waters doesn’t beat around the bush with weird dreams this time. He manifests in person and gives Turgon explicit directions on where to look: the well-hidden valley of Tumladen in a section of mountains just west of the spider-haunted Mountains of Terror, Ered Gorgoroth. So Turgon treks out to this secret place alone, taking the visit of a Vala quite seriously. Now, having seen the vale with his own eyes, Turgon goes back to Nevrast, hangs with his people, and starts working on the blueprints for the amazing city he intends to construct as a tribute to old Tirion.

Yeah, the kids and grandkids of Finwë have been busy this chapter! The names can get still confusing, even this far in. So let’s review what’s going on with them.

It’s around this time that Morgoth finally decides it’s time to test the Elves again. Maybe with all their feasts and peaceful meetings they’ll be ill-prepared for another fight, so he sends some Orc hosts out across the plains again. Heralded by “vomited flame” from peaks in the Iron Mountains, and even by earthquakes, the Orcs spill out from Angband’s gates again in large numbers. It’s been a while!

One wave goes west and tramps through the Pass of Sirion, while another rounds the mountains in the east and hikes through the lands Maedhros and his brothers had claimed. They’re not so much single armies as scattered bands terrorizing anyone they can find. Then a more central force pushes right in towards Dorthonion, which is the highland where some of the other sons of Finarfin have settled.

But Fingolfin and Maedhros have actually been watchful and are ready for this. They rally their own forces and clamp down on the Orcs on either side. Retaliating fast and hard, the Noldor mop the floor with the Orc bands before going on to crush the central host. Once more the Eldar chase their foes back across Morgoth’s front yard of Ard-galen and slay every single one of them. This effort goes up on the Wars of Beleriand list as Dagor Aglareb, the Glorious Battle. That’s two great victories for the Elves now.

We should probably start a list…

Not only is this a victory for the Noldor and a moment of solidarity between Fingolfin and Maedhros, it unifies them in the leaguer, or siege, that they realize they’ve got to begin. Both draw their forces in closer to Angband, and this does hem in Morgoth for a very long time. His servants are rightfully fearful of Noldor blades. But…

Fingolfin boasted that save by treason among themselves Morgoth could never again burst forth from the leaguer of the Eldar, nor come upon them unawares. Yet the Noldor could not capture Angband, nor could they regain the Silmarils; and war never wholly ceases in all that time for the Siege, for Morgoth devised new evils, and ever and anon he would make trial of his enemies.

Ugh, never boast, Fingolfin! But even though this is kind of a stalemate, the truth is the Noldor have contained Morgoth. He still sends out spies, if not armies, and as the years roll by he even manages to send out small Orc bands to capture some Elves alive. These are brought before him and with his own eyes he instills in them a terror they’ve never known. This introduces a horrible new stigma in the cultures of the Eldar, a “fear and disunion” that we’ll see more of in days to come. Morgoth will cetainly “not lack of a harvest” from this forced dissension.

Thus he makes from his Elf captives a variety of slaves, first learning from them, then putting them to hard labor, and then eventually setting them free. Free but enthralled, fearful to cross him, and so even when they’re recovered by their kin they’re never wholly trusted again. I mean, what if they’re spies now? What must it be like to look in the haunted eyes of an Elf who, being an Elf, has seen the beauty of Valinor and the light of the Trees and yet has looked into the face of Morgoth firsthand? An asshole of the first order, that guy is.

Another hundred years goes by in relative peace—not counting the disquiet of the occasional catch-and-released Elf—and Morgoth decides to test the leaguer. A bunch of Orcs heads out to the west along the coastline, but they’re too small a force and are so soundly eradicated by Fingon and his Hithlum-dwelling folk that no one bothers to give the conflict a name. Well, being Elves, I’m sure they did, but it’s not “reckoned among the great battles.” It doesn’t go up on the big Wars of Beleriand board.

Then another hundred years goes by.

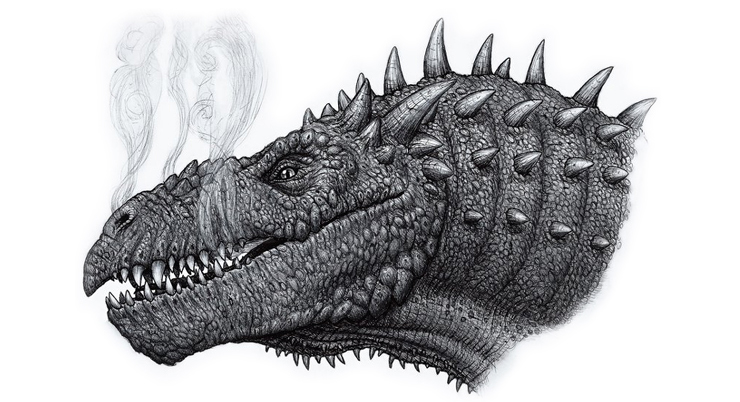

One night, out of the main gates of Angband comes something no Elf’s even heard of before. A fire-drake! A dragon! The very first of his kind, fresh from the monster-making basement labs of Angband. Glaurung is his name, father of all dragons, and Morgoth didn’t actually mean for him to bust out just yet; but clearly someone—maybe some Orc who turned his back on the cage at the worst possible time—screwed up, and out Glaurung went! Now he’s still young, and dragons live long; he’s barely half the size he’s going to be.

But dragons are no joke. They’re still big and terrible beasts, and in time we’ll even see how cunning and downright underhanded they can be. Especially this one, who’ll prove to be the mightiest of his kind (if not the physically largest). Like all of Morgoth’s creatures to date, Glaurung has no wings, but he still has a breath of fire and his mere presence “defiles” things. Dragons in Tolkien’s legendarium might be wonderous, after a fashion, but they’re not as elegant as dragons can be in other stories and worlds. There is a loathsomeness to them, and the older they get, the fouler they become—and these creatures have an ecological impact as well. They’re walking biohazards.

The Elves fall back from Ard-galen, dumbfounded and dismayed by this unexpected R&D project of Morgoth’s that’s just been unleashed. But eventually, before the dragon gets too far, Fingon rides with his Hithlum warriors and they pepper him with arrows. As armored as dragon-hide must be, Glaurung is bothered by this. Let’s just say his Armor Class and Hit Points just aren’t what they’re going to be, many years from now. So he turns and flees back to Angband.

But Morgoth was ill-pleased that Glaurung had disclosed himself oversoon;

You just know the Orc responsible for Glaurung’s premature release definitely got sacked. Well…“sacked.” And don’t mistake it, dragons are smart—very smart, even this first one. Merely with words, some well-placed seeds of doubt, and the power of his gaze, Glaurung is going to do far more damage in chapters to come than any rake of his claws or blast of his breath.

Strangely, though, the Elves don’t take Glaurung too seriously. Maybe they think the drake was just some strange anomaly—when really the takeaway should be, “Holy crap, Morgoth’s breeding some crazy new monsters! What else has he got up his sleeve?!” But instead, two hundred more years are going to pass with little conflict except for some unnamed skirmishes on the borders. Beleriand prospers, the Elves generally get along with one another, and they get to work putting more roots down.

Things are looking up.

Just a warning, though: You, dear first-time reader, probably won’t be prepared for the high-octane, action-packed thriller of the next installment of this Primer, in which I tackle the legendary roller coaster thrills of Chapter 14, “Of Beleriand and Its Realms,” and the verbal discourse of “Of the Noldor in Beleriand.” Buckle up!

Top image: “Fëanor’s Last Stand” by Kenneth Sofia

Jeff LaSala, on his death bed, would never make his son renew a terrible, life-scathing oath. What the hell was Fëanor thinking?! Tolkien nerdom aside, he wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books.

Also… Is it wrong that I now want a little three-dimensional Maedhros refrigerator magnet? Get on that, Tolkien readers with an Etsy shop!

Awesome summary, Jeff! Love it. Is there anything as truly epic as the Silmarillion? Btw, I’m proud to say that my first email address was Maedhros9@aol.com, even if it didn’t survive the 90’s.

Wow, this is a lot :)

And so passes the most mightiest and talented of the Elves, and also their biggest asshole (speaking of, it is a travesty that now that The Toast is gone, so is the Most Metal Deaths of Tolkien, Ranked. It lingered for awhile, but all the links are broken now. I did save it on my personal computer offline though, ha!). So metal he turned to fire as he died, lol.

And yeah, swearing your kids to an oath that will kill them is pretty assholish. Maedhros probably would have been a pretty stand up guy otherwise.

Nice job on an epic chapter! This bit in particular made me smile:

Like I said, Elves have trouble focusing on things like warfare. It’s much more fun to build and make up new names. They weren’t designed for high impact murderous conflict. Guess who was.

I wonder if there’s solitary confinement in the Halls of Mandos. Fëanor seems like he deserves more than just never getting re-housed for as long as the world lasts. But do doubt having all that creative fire and no body to implement it has to be a form of Hell.

@2, nice one! AOL.

Just as Maedhros didn’t survive the First Age. :(

@3, I know. It’s very difficult to be concise when you’re talking Tolkien.

@5, not sure I agree. If you’re talking about Morgoth, I wouldn’t say he was designed for high impact murderous conflict either. That was his idea. Now, it’s fair to say he’s put the most thought into the matter.

@6: The Valar grieved over Fëanor. I don’t think anyone would be interested in tormenting him.

1) I bet the Orc who let Glaurung out was sacked. In a literal sack. Thank you Josh Whedon for that one!

2) Melkor invents personal injury law! The firm of Gothmog, Gothmog, Shelob, Angmar, and Gothmog is founded in this chapter. A personal injury firm, injuring persons since the First Age. How did they get Fingolfin’s action against Melkor thrown out of court? On technical Gronds!!!!!

There is a meme floating around where Galadriel takes Gimli to Mandos to stick their tongues out at Feanor and show him the hairs she gave the Dwarf (but wouldn’t give him). Now that’s punishment!

@3 Lisamarie, the Wayback Machine is your friend for finding stuff like that:

https://web.archive.org/web/20180128060851/http://the-toast.net/2015/06/23/the-most-metal-deaths-in-middle-earth-ranked/

@7, I didn’t mean Morgoth. I meant Men, and Dwarves too. Aule designed his children to be enduring and strong in mind but they have this fertility problem that makes keeping up their population under pressure difficult. Men breed like mink regardless of circumstances, can actually get off on lives of constant conflict and have a basic situational awarness that Elves seem to lack and are less likely to get distracted by the shiny.

IMO Feanor is his own punishment. He isn’t being kept in Mandos by Mandos but by his own refusal to repent of follies. He won’t learn from his mistakes so he can’t move on.

I believe it’s Dagor-nuin-Giliath, not Dagor-nuin-Gilith.

Really enjoying following along with your reread.

Excellent and entertaining summary. Props.

Princessroxana, I’m not fully convinced. I think most/all sentient creatures lean to defend themselves as needed. Men no more or less than anyone else. I think if Men were more prone to war than Elves, they’d be generally better at it. But I doubt, for example, that at the height of their power (probably Númenoreans) any force of Men would have been able to match the Noldor when they came over to Middle-earth. And I don’t just think that’s because the Noldor are “tougher.” I think their skill in arms was also at its peak.

@12, Yikes, yeah. Thanks! I’ve fixed that; have to fix my graphic later.

I know we are here to talk about the Silmarillion but having read the The History of Middle Earth series, I just would point out that if Tolkien’s last word on the “making” of Orcs was the correct one, this chapter would need a massive rewrite. Because all those Orcs that Feanor and company killed in the 2nd Battle wouldn’t have been around yet. Tolkien’s last word on Orcs was that they must have been “made” from Men and since the 2nd Battle happened before men woke up (at the rising of the Sun for the first time), Orcs couldn’t have existed yet. And I understand why he did it, because the whole concept of the Elves’ fea being indestructible doesn’t comport with the idea that Orcs originally are Elves who were twisted by Morgoth. But it left him with a conundrum as to who to have the Elves fight before Orcs could exist.

I just re-read the Silmarillion myself, and that was a huge downer. Captured elves were screwed over twice – first when they were captured and enslaved, and then a second time when their own kin treat them with fear and disdain because of the (very real) possibility that Morgoth has brutalized them into being his servants during their captivity. Tolkien had a good, almost understated line about it – something involving “desperation”.

Exposition dump, Tolkien style!

@14, it’s not ability it’s affinity. Elves are great warriors but basically they prefer other occupations. They keep letting their guard down like they’re forgetting the whole reason that they are there in ME in the first place.

I guess I think it’s just speculation on our part. For all the Elves’ dislike of war, and their “letting their guard down,” I’m just picturing an equal number of Men in Beleriand during this same time frame and trying to imagine whether they’d be any better (or worse) at maintaining the leaguer against Morgoth, or for as long as the Elves manage it.

I mean, I do think in Tolkien’s world Men are super plucky. They have to be. I just don’t see calling them as more designed for war.

@16: Not so much exposition in “Of Beleriand and Its Realms” as stage setting. But heck yeah, this is arguably Tolkien at his Tolkienest.

@10 – ha yessss! I was going to check the wayback machine when I got home :)

@18, the timescale would be hard for Men. To us a century is a long time and even a mere twenty years is a significant bite of a lifespan. On the other hand France and England had no problem keeping up a state of war for a hundred odd years.

Maybe it’s just early socialization. Elves were protected by the Valar and carried off to Aman. Men got to face Morgoth and his critters first off.

Since Tolkien was a medievalist, his repeated use of music-as-tracking-device probably has something to do with Blondel de Nesle.

Also, Jeff, I have for some weeks been preparing myself for “Of Beleriand and Its Realms.” :D

It occurred to me that Tolkien might have “marked” the progression of Fëanor’s fall by the people he betrayed and when he betrayed them.

1) He betrayed the Valar first. He treated them with contempt and he refused to give them the Silmarils. The Valar weren’t his kin, but they were the rightful lords of Valinor and (in my opinion) the rightful owners of the light of the Silmarils.

2) Then he betrayed own race (the Elves) at Alqualondë.

3) Then he betrayed own people (the Noldor) when he burned the ships at Losgar.

4) Finally, he betrayed his own family when he commanded his sons to fulfill an Oath that he knew was hopeless.

If he hadn’t died at that point, I wonder what he would have betrayed next. His own body? Maybe he would he have literally cut off his own nose to spite his face.

Somewhere on youtube there’s an interactive map of Beleriand in the Silmarrillion showing all the kingdoms over time, also the routes of the armies and whatnot. It’s pretty fascinating and useful. I don’t know how to post a link here or I would.

My headcanon is that Feanor put so much of himself in the Silmarils that he’s not sane without them on him or nearby. He does say he’d die if they were broken, – excuse me “I shall be slain”. And he’s grieving for his father, but he can do something about the gems, so that’s a large part of what drives him. He’s completely lost all sanity by his death, though. I do wonder if he and Finwe spend time together in the halls of Mandos, maybe even with Miriel. But since no Eldar besides him dies in ash, as he does, I also wonder if he wasn’t all Eldar, but something more, as Huan was.

Overall, there’s something very unsettling about people’s reactions to those gems. All but Beren, and maybe him, too, considering some of the stuff in HoME, cling to them, above people.

I don’t like most of the Valar and what they do. They seem to either over or under do stuff.

My kid pointed me to a fanfiction of the Beren & Luthien story guaranteeing it wasn’t graffiti on the Mona Lisa, and 3/4 of it is set in the Halls of Mandos while Luthien argues her case with the Valar. It’s called A Boy, A Girl, and A Dog: The Leithian Script. Draws a lot from HoME, and can be quite good, if anyone wants to look it up. it’s on An Archive of Our Own. In it Feanor’s wife visits the Halls and is heard to remark “He gave up a Silmaril for thee? Child never let him go” to Luthien.

I’ve been meaning to bring up the Leithian script. Full of great moments. Beren hears about Amarie and tells Finrod from the depths of his own romantic experience that he, Finrod, messed up bad.

@24, yes, the great “you jilted her – no wonder she punched you halfway across the dinner table” scene. And Finrod’s eventual ‘your people have a word for it. It’s wise to listen to experience” conclusion.

The first thing worth asking is, how wide is thirty fathoms? That’s 60 yards or 180 feet. That’s as wide as the Leaning Tower of Pisa is tall.

To put it in different terms: Thorondor has a wingspan of 180 feet. A Boeing 747 has a wingspan of 195 feet.

So much trouble could have been prevented if the other Noldor would have just given Feanor a swift kick in the Silmarils instead of their attention every time he opened his mouth.

In addition to the fraught textual history and philosophical wrangling of “What are Orcs, anyway?” that previous posters have cited, the end of this chapter brings up a similar problem. What are dragons? Both Glaurung and, to a lesser extent, Smaug are much too intelligent to be animals. (Sorry, Huan, but you don’t come close on linguistic intelligence here, and it’s Tolkien so that counts for a LOT.) But they’re definitely material, as opposed to Balrogs which, uh. . . [shows self out briefly before re-igniting, pardon the pun, the Great Balrog Wing Flamewar of the late-90’s Internet].

Ok, anyway, they’re undisputably fully material beings. They eat, they permanently befoul places they have been, they have definable physiological weak spots and therefore organs. So what the heck are they? Even if we assume that Morgoth has started with some kind of reptilian breeding stock and bred up to monstrous size, what is the nature of their intelligence? If they are Maiar inhabiting animal bodies (perhaps a bit like we might imagine “werewolves” and “vampires” to be), why do they take so much longer to emerge than Balrogs?

Don’t get me wrong. Tolkien’s dragons are wonderfully done and I can’t imagine the story without them. But I have a sneaking suspicion that, after Beowulf, he couldn’t imagine the story without them either and never quite got around to thinking through a way to make what he’d already written mesh with the later cosmology and philosophy. Unless I’m missing something?

P.S. I don’t have a citation handy, but I’m 99.9% sure that Gothmog the Mouth of Sauron is definitely a Man (specifically a Black Numenorean) in the text. Perhaps OP is getting confused by Peter Jackson’s truly terrible decision to miss an opportunity to Not Have All the White Men With the Good Guys and to portray the Mouth of Sauron as a monster instead?

@28

Gothmog the Lieutenant of Morgul (Angmar’s second-in-command, who took over the forces of Mordor at the Pellenor Fields after the fall of his boss) is a different person from Mouthie who is specifically described as a Black Numenorean. We are given no information about Gothmog other than his name and rank; I have presumed that the second-in-command to the Chief Nazgul would also be a Nazgul but that is unsupported. I do know that he was a lawyer (and partner at Gothmog Gothmog Shelob Angmar and Gothmog) but that is an entirely different discussion. I note that Gothmog was present when Grond was used to knock on the doors of Minas Tirith and I can only imagine that Melkor is smiling at that…

And I agree that the pooch is not in the “sentient animal” class. Meow.

Morgoth didn’t actually mean for him to bust out just yet; but clearly someone—maybe some Orc who turned his back on the cage at the worst possible time—screwed up, and out Glaurung went!

John, Morgoth, the kind of control you’re attempting simply is… it’s not possible. If there is one thing the history of evolution has taught us it’s that life will not be contained. Life breaks free, it expands to new territories and crashes through barriers, painfully, maybe even dangerously, but, uh… well, there it is. Life…. life finds a way.

@15, Tolkien had all kinds of contradictory ideas, I’m not bothered by those. I think every world-building author does. Difference is, unlike a lot of big- and small-time writers, Tolkien got a lot of his unfinished ideas published. It’s all food for thought, and because it’s Tolkien, it’s all very interesting but it doesn’t make it canon. Sure, even The Silmarillion itself can be nebulous because it was published posthumously, but I consider Christopher Tolkien’s treatment pretty darn authoritative.

I’m not one for much actual “headcanon”—I just prefer what we’ve been given—but I personally like where Tolkien was going with Orcs in Morgoth’s Ring. Which I think also includes the bit about Orcs being made from Men as well later (not simply instead of Elves). I mention a little bit of it here, but I think it most likely that Morgoth tormented his early captured Elves and made from their bodies the first generation of Orcs, but from there on they were simply bred like bad carbon copies. Tolkien’s talk of Orcs as talking beasts makes sense. They’re not Children of Ilúvatar, they were made in mockery of them only. They have no fea, they go nowhere when they are slain, and are simply violent and warlike from the start…but also hateful and fearful of Morgoth. During those stages when there’s no Dark Lord in power (be it Morgoth or Sauron) they’re still tribal and savage but they don’t have an evil will organizing them and driving them to attack the world of Men or Elves in force. And even when Sauron takes charge of them, they still squabble and fight with one another as we see in Cirith Ungol and on the plains of Mordor.

But Tolkien was also one to leave some things unexplained and mysterious. Tom Bombadil, the Entwives, etc. I think Orcs are part of that, as are dragons.

Dragons seem like beasts reared or bred of reptilian stock, sort of like Carcaroth is from werewolves, who in turn are like especially nasty wolves that are then bound with some form of evil spirit. I think Morgoth clearly exerted (and squandered) his power making dragons in a similar way, but they’re even mightier. I don’t think they’re Maiar. There does seem to be an ambiguous caste of spirits brought into Arda by the Valar and Maiar that are not Ainur. Witness the Eagles. Even Ents perhaps, since Ents are a sentient people but are not Children of Ilúvatar. They’re not even of the “adopted” variety of the Children that Dwarves become. They seem like advanced plants bound with some sort of Yavanna nature spirit.

@1 – no you are not wrong, and now this is something I also need.

Tolkien said explicitly (Letters somewhere?) that he never found an origin story for Orcs that satisfied him, because he could not account for a race incapable of goodness. It’s not like with Bombadil, whom he left unexplained because the mystery had its own value.

I once worked out from a chronology in HoME that Maedhros was pinned for at least several years, maybe decades, I forget. (In my mental image, unlike the painting shown here, it’s an undercut cliff, so that only his hand is in contact with the rock – held directly by a staple, not a chain.)

I’m thinking it’s more like, if you’re a fan of Tolkien, you just have to get used to some things never being explained. Whether mysterious by design or by omission (or just something he hadn’t gotten to around to resolving), these gaps somehow make it all seem realer. Real life is messy and inconsistant. At least that’s how I see it.

Oh, there’s tons of great illustrations of Maedhros on Thangorodrim (and some terrible, if well-meaning ones). There are many ways to interpret. And I think it’s in the Annals of Aman that it’s suggested that it’s about five years between the rising of the Moon and Sun and Maedhros’s rescue. But even that’s not official, really.

The Silmarils are a lot like the One Ring. Did Morgoth get some Feanor powers by wearing a Silmaril crown? Maybe the extra fire helped make dragons.

Sauron seems not to have learned anything from the Silmaril or he wouldn’t have put his power into an object that can be stolen by his enemies. Did he also swear an oath to persecute anyone who keeps his ring?

@35 birgit

I don’t think Sauron needed to swear an oath to persecute anyone. He’s just that kind of guy.

It’s interesting to compare and contrast the deaths of Feanor and Fingolfin. Both basically go up to Morgoth and yell, “Come at me, bro!” And both promptly get curb-stomped (literally, in Fingolfin’s case). But Feanor is sure Morgoth can be defeated and gets reckless; Fingolfin is sure Morgoth can’t be defeated and commits suicide-by-Vala.

A day may come when Maedhros has to take the ultimate dive and accept the end that his father’s Oath has made inevitable

…I see what you did there.

Just a warning, though: You, dear first-time reader, probably won’t be prepared for the high-octane, action-packed thriller of the next installment of this Primer, in which I tackle the legendary roller coaster thrills of Chapter 14, “Of Beleriand and Its Realms”

*snerk*

@8: That was terrible. I laughed.

@23: What does HoME say about Beren?

Thirding the recommendation for A Boy, A Girl, And A Dog. It’s a crying shame it never was finished.

@31

This. As far as I know, the only explanation for the origins of Eagles and Ents is when Manwë says, “Behold! When the Children awake, then the thought of Yavanna will awake also, and it will summon spirits from afar, and they will go among the kelvar [the eagles] and the olvar [the Ents]…” (Of Aulë and Yavanna). But if all we know about the Ents’ origins is that they were “spirits from afar,” that doesn’t tell us very much.

In his notes on the Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth (which appears in Morgoth’s Ring), Tolkien considered the possibility of other types of intelligent life in Eä. He was specifically concerned with life on other planets, but I think the same arguments could be used to suggest that there are many different types of spirits in Arda.

I’m not sure about that last part, where Elves assume that Arda must be the “dramatic center” of Eä. But in general, this passage seems to allow for the possibility that there are more spirits in Eä than just the Ainur and the Children of Ilúvatar. The existence of Dragons, Ungoliant, the Nameless Things, the Ents, Tom Bombadil, the “cruel” spirit of Caradhras, etc. might be taken as evidence to support this idea.

Incidentally, one of my pet theories is that Ungoliant and the Nameless Things were originally spirits that lived in the Void until Ilúvatar created Eä right on top of them. They were given physical forms against their will, and as a result they think of Eä as being a bit like a tacky housing development that was built on top of a pristine meadow. That’s why Gandalf told Gimli that the nameless things deep in the Earth are older than Sauron. Even though the Ainulindalë says that the first thing Ilúvatar did was to make the Ainur, maybe other spirits like Ungoliant are older than the Ainur. They weren’t mentioned in the Ainulindalë because they weren’t considered to be relevant to the theme of that story. Or maybe the beings that composed the Ainulindalë didn’t realize that such creatures existed. (I know it’s a bit foolish to try to reconcile The Silmarillion with The Lord of the Rings, but the effort makes me happy.)

@37, what HoME says about Beren regarding the Silmarils that makes me wonder if he was free of the pull after all, was (fetches volume.. no, not that one.. not that one.. grumble, won’t they put out an ebook edition of it all so I can search..grumble … ok Book of Lost Tales #2 also the Beren and Luthien book ). It might be just curses on gold, but I suspect the Silmaril on top of everything else – what do you think? (please forgive length, I made it as short as I could.)

Melian saw the Nauglamir cursed twice over as having been part of Glaurung’s hoard, then by Mim the Fatherless, one of the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves, who supported Morgoth. Here’s that background:

Hurin dragged the hoard to Menegroth (he had men to help) and threw it at Thingol, where everyone was affected by the spells woven over it.

Then Elves& Men all fought over the treasure and Thingol’s forces won very bloodily. Melian told Thingol don’t keep it, don’t touch it, just get rid of it. Thingol doesn’t listen: had it remade into stuff for him, by Dwarves who really don’t want to work him and cursed it again. That’s three curses at least.

Then he had them go back and add the Silmaril to the Nauglamir and was murdered for it.

Beren avenged him. As he kills the Dwarf who murdered Thingol who was wearing the Nauglamir cursed it and the treasure again.

That’s the background to how it comes back to Beren.

Beren threw all the treasure in the river except the Nauglamir with Silmaril which he takes home to Luthien:

“Then did he unloose the necklace and gazed in wonder at it — and beheld the Silmaril, even the Jewel he had won from Angband and gained undying glory by his deed; and he said: ‘Never have mine eyes beheld thee O Lamp of Faery burn one half so fair as now thou dost set in gold and gems and the magic of the Dwarves’ and that necklace he caused to be washed of its stain and cast it not away but bore it back into the woods of Hithlum.”

Came home with it. Stuff happens, Melian arrived & upon seeing Luthien wearing it ‘wrathfully’ asked Beren why he suffered the accursed thing to touch Luthien. Beren doesn’t understand the problem. Melian listed off all the curses on the gold and the necklace. Beren laughed. Silmaril will overcome all evil. Melian pointed out it didn’t before.

He’s got a Maia telling him that thing is bad news and doesn’t listen.

Luthien says she doesn’t desire gold or jewels, even the Silmaril, over the Elven gladness of the forest. Takes it off. “To the pleasure of her mother she cast it from her neck, but Beren was little pleased and did not suffer it to be flung away, but warded it ever in his [smudge]. Probably keeping or treasury or something of the sort. Now, in the Beren & Luthien book that came out recently it also says…Melian warns them ever of that curse, dwells with them and warns them ever, and they keep it anyway. And Luthien wears it to please Beren.

He can’t give it up, even when a Maia, someone who really ought to know, tells him to do so. Now it might be the curses on the gold, but what he focuses on is the Jewel. We already saw Feanor be like this about them. And the Ring… it’s a Tolkien thing, so it’s easy to read it in here, too.

@18 We don’t have to imagine that in the abstract. That’s the history of Gondor.

@40, true that Gondor was also in a sort of leaguer with Mordor. Very good parallel to make! But I think the scale is quite different. Mordor is a shadow of what Angband was. And even during the most peaceful of times in Beleriand, Morgoth was capturing Elves and sowing discord. I don’t think Sauron had quite the same effect, though certainly a lot of what he does in the Third Age is his version of Morgoth’s Greatest Hits.

@39

No one ever listens to Melian. Not Beren, not Thingol. She’s thinking of changing her name to Cassandra…

@41, Well, it would be consistent with your premise to think that Gondor had an easier task and failed at it earlier. It is also consistent with the general idea that everything in the Third Age is smaller and weaker than what happened before.

That said, I don’t really how to compare the military effectiveness of the Numenorean host that comes over to Middle Earth to unseat and capture Sauron in the Second Age with the Noldor, when they first arrive. The Numenoreans achieve their goal (at least at first), so the campaign is more effective. But, from the perspective of the legendarium, I think we have to assume that no single Numenorean champion would have been able to go toe-to-toe with a Noldorin counterpart (let alone a worked-up Feanor).

It’s kind of weird, though. As far as we know, the Noldor have never really done much fighting (aside from the Kinslaying, which was essentially a surprise attack against an equally untested force) so where did that skill come from? According to the legendarium it seems like all skills are innate and finite resources; nobody really gets better at anything through practice, or by building on the past, whether art, craft, skill, or otherwise (except for some fairly quick initial learning curves). It’s an RPG where you start as an epic character and then level-down as you do things.

To be fair, the Silmarillion just can’t cover all that. And all Tolkien’s History-type writings concern topics he cared much more about. He wasn’t a military history buff, just a medievalist and philologist and fantasy writer. Granted, the Elves are a special sort of race we can’t quite understand, but for the most part I think we can fill in the blanks with some basic assumptions. The Noldor were probably amazing hunters and athletes even before Melkor introduced the very idea of warfare to them, and prompted them to forge weapons. Once they had those, they did what Elves do: they master things. I think even without Orcs to hone their skills against they still sparred and, being elves, made it a martial art. Of course, we’d all love to hear more about that aspect of their culture. But Tolkien had only so many hours in the day, and he enjoyed nomenclature far more than martial tactics.

@44 Remind of Robert Jordan’s hints in the Wheel of Time about the sport of swords being turned into a real fighting style in the Age of Legends when Evil showed up.

It occurs to me that these articles are as much of a translation as the professor’s work on Beowulf.

And do we believe that the Elves on that centuries long journey to the West never ran into any Orcs or other assorted nasties that needed killing? They may well have developed weapons before getting to Aman. And those who didn’t go overseas had to fend for themselves, and develop defense and martial arts.

@39 To be fair, Beren and Luthien were sort of required by fate to hold on to the Silmaril.

SPOILERS

I don’t have the book handy right now, but I recall that it’s either explicitly stated or at least strongly implied that it was only because he had a silmaril to light his way that Eärendel was able to pass through the snares and enchantments that kept everyone else from reaching Valinor. So if B&L take Melian’s advice and get rid of it, then no voyage of Eärendel –> no War of Wrath.

@43

I can’t find a primary source, but I believe that Hador, a human king from the First Age, was considered to be a peer of the Elven lords. And Húrin his grandson apparently once killed seventy trolls in battle (though perhaps that feat would not be considered extraordinary if a Noldo had done it).

@46, I don’t think so, no. There could have been some of Melkor’s beasties about, but the Noldor and Vanyar especially, who more or less stayed close to Oromë, probably wouldn’t have been very troubled by them. And definitely not Orcs, not yet. Elves didn’t have any eyes on the Orcs until the “Of the Sindar” chapter, and then only the Teleri/Moriquendi who stayed behind encountered them. The Noldor would know nothing about Orcs until they returned to Middle-earth.

Man, though. I would happily read a chapter, if Tolkien had deigned to include one, all about the philosophical debates that might have enfolded once the Elves did meet them. After those first battles. It’s not really told when the Elves came to understand that it was the Avari Melkor first made them from.

@47: Indeed, you are correct in that sense.

@37, I was momentarily puzzled by that description of chapter 14 since I didn’t remember any thrills or chills. Irony went right over my head, what was I thinking? Its actually quite an interesting chapter in it’s way but should be read with a good map of Beleriand at hand.

A Boy, A Girl And A Dog is an incredibly long unfinished fic that is bloody addictive, I’ve been reading steadily through it for the last three days. And that was just the section set in the Halls of Waiting. Basically Finrod Felagund and the others who died in the pit rally round Beren and Luthien, and are very snarky. Valar talk interminably, Maiar bustle in and out. Tulkas and Nessa are no help at all. Assorted living Noldor are called in to help but don’t much. Finrod rallies allies among the departed. Unwanted relatives and Feanorians show up as do two angry exes. All of this is resolved before the abrupt end though a new issue has arisen.

@49 maybe. OTOH, they built their city in Aman with walls, and why would they have developed such a habit?

Ok you have to be reading carefully, or the mentions of white walls could be walls of houses, but Feanor is mentioned as being at the gates of Tirion, which means a city wall that the gates are in.

Although really I think Tolkien just assumed walls because in the stuff he studied for his passion and paycheck, all cities/towns/centers of living had walls.

@39 I recall from the Sllmarillion that the Wise speculated that the Silmaril shortened Bergen and Lúthien’s life spans- its flame being too bright for mortals.

@52:

With Thingol, Menegroth, the Sindar, and the Dwarves, I think walls are just sensible. Moreover, with Dwarves involved—who are accustomed to subterranean strongholds—walls and gates are just a given, anyway. Anyway, I think the Eldar on Middle-earth had some beaties to deal with, so walls are a no-brainer.

But in Valinor, even when the Vanyar, Noldor, and Teleri arrived, there was already Valmar, a city wrought by Valar (and probably Maiar), and it had walls and gates. Either because the Valar had already learned to be defensive as a result of Melkor, or because they’re just foresighted and know the world is going to need walled settlements, it simply was. And so the Noldor, seeing that, would of course place walls and gates on their cities thereafter.

The walls could have been a decorative boundary setter to prevent sprawl.

Does Tolkein ever specify the sizes of the various forces and groups? I’m trying to get a sense of the scale – when he talks about bands of orcs being sent out are we talking a few hundred, or Return of the King size, or bigger? How many elves were in the different cities?

@56: Almost never! Certainly not in The Silmarillion. It’s frustrating at times, but there are moments where I come to actually appreciate the vagueness. But yeah, it’s always hosts, kindreds, portions, armies.

@56, 57 Would Tolkien have run into the problem of historians and chroniclers providing wildly implausible numbers for armies and battles? It could be he was deliberately dodging the issue. It’d make it easier to fudge the logistic requirements, too.

Tolkien was in most ways meticulous and deliberate with his wording. So I’d regard things like this as intentional omissions more than dodging. When he’s specific, it stands out. Fëanor was exiled from Tirion for twelves years exactly (though possibly not solar years), for example. Why twelve? Why not just say “for a time,” or whatever as he often does. He seems to pick moments to be specific.

He also seems to take into account, more than we do most of the time, what his narrative point of view is. These are ancient and mythic stories told by Elves but “translated” by Men and passed on. Hard numbers don’t become such things, except those that matter. There were the Twelve Labors of Heracles, but how many Argonauts were there? (Sure, some accounts have some guesses, but in the stories, are numbers always given?)

Time in the ages before the Sun and Moon are even more vague.

I’d don’t like Feanor, who could? But I have sympathy for him. The basic problem is a fiery, restless, creative being like Feanor doesn’t belong in ordered, well governed Vallinor in the first place. Whatever mission his exceptional spirit was sent into Arda to accomplish was frustrated from the get-go by the fact he was born in Aman not Middle Earth. The loss of his mother must have made him feel both different and deprived and it’s understandable that he would have resented Indis and her children. Understandable but also unworthy of a noble Elf. Melkor had a lot to work with here. It is my firm conviction that the light of the Trees, a hoarded blessing, was tainted by by the sin of covetice a taint that passed to the Silmarils. Because it is inarguable that the ‘Holy Jewels’ had a disastrous effect on the minds of most people who possessed or even desired to possess one beginning with their creator and continuing through the First Age and the War of the Great Jewels.