Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

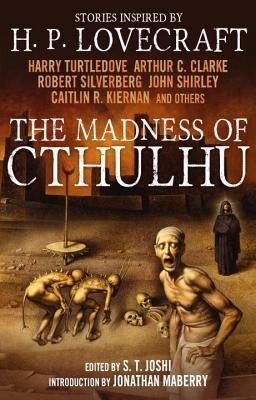

Today we’re looking at Caitlín Kiernan’s “A Mountain Walked,” first published in 2014 in S.T. Joshi’s The Madness of Cthulhu anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“What was witnessed, for all its horror, I cannot wish to forget as it hints at a world even more distant and ultimately impervious to our understanding than the bygone ages and their fauna hinted at by our diggings.”

Summary

We read, verbatim, excerpts from the field journal of Arthur Lakes, made during an expedition to the Wyoming Territory in 1879. At Como Bluffs, with the assistance of “bone sharp” Bill Reed, Lakes and party have been unearthing the fossil treasures of the Jurassic and Cretaceous. At night the fellows tell tall tales around the fire, and Lakes reads books of natural philosophy to Reed. Ah, manly good times.

The good times start to sour when Lakes and Reed hear a peculiar booming at sunset. Then a foul-smelling, oily spring burbles up into a quarry, threatening excavation. While Reed’s supposedly hunting antelopes, Lakes watches him instead fire straight into the sky. Reed won’t say what he was shooting at, though he does point out a worn trail several feet wide and a half mile long, the product of jackrabbits. Um, jackrabbits?

Professor Othniel Marsh of Yale arrives. He tours the quarries with Lakes and Reed. All are dismayed to find the promising Quarry 3 inundated by the foul oily spring. But near Quarry 4, Marsh is pleased to discover the stone fetish of a winged demon. Reed’s reaction is the polar opposite—he anxiously advises Marsh to leave it where found, lest the Sioux or Cheyenne take umbrage and cause trouble. Marsh refuses. The piece will make a valuable addition to Yale’s Peabody Collection; he carries it off in his own pocket.

On their way out of Quarry 4, a doe elk bursts from the brush and dashes at Reed. He shoots her but she escapes, leaving a trail of too-dark, sulfurous blood. Marsh suggests she may have drunk from the oily spring at Quarry 3. More troubling to him is Reed’s superstitious fear of Indian relics, no qualification for a collector!

This not-so-veiled warning doesn’t keep Reed from muttering about little-understood perils of the prairie, and pressing Marsh to return the fetish. Lakes wonders that Reed, a seasoned hunter and veteran of the Union army, should suddenly become so wildly credulous. Still, one has to admit, portents multiply. A blood-red ring around the moon precedes a days-long dust storm. Animals tainted with the oily sheen convince the party it’s unsafe to continue eating local game, curtailing their food supply. The eerie booming sounds again, unsettling even Marsh.

Then the crisis comes. The night before Marsh’s return east, Reed draws the attention of the campfire circle to – silence. The usual nocturnal chorus of coyotes and owls has suddenly stilled. Even the wind holds its breath. Once more Reed argues with Marsh about the fetish. A party member points at the sky. Reed lifts his rifle and fires two shots into the darkness.

As Lakes stumbles up, drawing his revolver, a naked woman steps into the clearing. Or some approximation of a woman, “slow and smooth and graceful as a lion bracing itself to pounce upon its prey.” Her unblemished skin and hair are fresh-snow white. Her inner-lit eyes are bright blue. Eight feet tall, with insect-lanky limbs, she’s as beautiful and wraithlike as one of Poe’s creations, goddess-glorious. To Marsh’s quavering queries she makes no reply, though she regards him with intense curiosity.

The woman would have been haunting sight enough, but Lakes has the misfortune to look above and behind her, where “towering…even as a cottonwood tree will tower above a pebble…was some indistinct shadow that blotted out any evidence of the stars.” As it shifts slightly, as if from foot to foot, Lakes wonders why the earth doesn’t rock under it.

They all know what she’s come for, Reed says, and that they’ll be damned if it isn’t returned. Marsh still protests; Reed levels his rifle at him. The woman stretches out her left hand, confirming her desire.

What prompts Lakes to point his revolver at her, knowing she’s as far beyond destruction as the mountainous shadow, he can only explain as the human impulse to drive back harm. In fact, he can only stand witness to Reed informing Marsh that his rifle will speak next, to Marsh cursing but taking the fetish from his pocket.

The woman’s smile will haunt Lakes’ dreams forever. She doesn’t reach for the fetish, but it vanishes from Marsh’s hand, appears in hers. He cries out—next morning Lakes will learn that his palm has been badly frostbitten. The woman pays no heed, flowing back into the darkness; the mountain shadow lingers a little longer, then withdraws without a sound, without a tremor in the planet it should shake pole to pole. As the nocturnal chorus sings out again, as Reed sinks to the ground and cries, Lakes realizes the shadow really was merely that, a shadow, and he can’t conceive what actual being could cast it.

Soon after Marsh’s departure, Reed leaves the Como expedition. To Lakes’ surprise, all the rest stay on. None of them have spoken of the night the white woman came for her fetish, or of what loomed over her. Every night, though, Lakes glances skyward with the dread of seeing the stars “obscured, by what I will not ever be able to say.”

What’s Cyclopean: The sky-blotting shadow earns only a “titanic” rather than a “cyclopean,” but is at least admitted to be an “abomination.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Marsh mocks Reed for his “fear of Indian relics.” It’s not clear that the artifact in question is, in fact, “Indian.”

Mythos Making: The title is a quote from “Call of Cthulhu.”

Libronomicon: Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation is an 1844 work of “speculative natural history” by Robert Chambers. It posits a universe of continually changing forms, aiming toward perfection.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Lakes, observing Reed’s agitation, fears for his sanity.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Marsh and Cope’s bone wars. Cthulhu’s dread rise from R’lyeh. These are two great bases for a story that go well together, and “A Mountain Walked” is a nice piece of creep that combines them. And yet, I keep thinking about ways they could combine more intensely, more awesomely, into an unholy hybrid the likes of which we’ve barely glimpsed. I guess I’m just hard to please.

So, last things first, the title is of course a quote from “The Call of Cthulhu.” The stone amid R’lyeh’s non-Euclidean geometry is pushed aside, something indescribable emerges, and “A mountain walked or stumbled.” I can’t blame either Kiernan (or Joshi in his anthology of the same name) for snatching that perfect title. For those who write Lovecraftian humor, I’m pleased to report that “A Mountain Stumbled” apparently remains unclaimed. Cleverly, the scary thing in Kiernan’s story isn’t Cthulhu Itself but more likely the first thing that comes out of that R’lyehn cairn:

The aperture was black with a darkness almost material. That tenebrousness was indeed a positive quality; for it obscured such parts of the inner walls as ought to have been revealed, and actually burst forth like smoke from its aeon-long imprisonment, visibly darkening the sun as it slunk away into the shrunken and gibbous sky on flapping membranous wings.

We know that’s not Cthulhu, since that entity squeezes “Its gelatinous green immensity” out the door immediately following. Unless, like Peter Pan, Cthulhu goes about chasing Its accidentally detached shadow. Which is totally plausible.

The Cthulhoid crisis in “Call” takes place in 1925. The timing doesn’t quite line up for the Bone Wars, the fabled late-1800s rivalry between paleontologists Marsh and Cope, but we’ll allow it because the elder gods are timeless (astral correctness aside). Also because realistically speaking, who among us has not wanted to read (or write) the story of Othniel Marsh, wayward Deep One, trying to reclaim the lost histories of the Cretaceous in the drylands of Wyoming? Racing against time, and against Edward Drinker Cope who is, I don’t know, working for the last of the Elder Things or something. Maybe there are some cone-shaped-being fossils out there, hidden amid the allosaurs.

Ahem. In any case, Reed and Lakes really were out by Como Bluffs in June 1879, and Marsh really did visit them at that time, and R&L really did not get along well. This week’s story is certainly a novel explanation for what passed between them, and a more entertaining one than “bunch of alpha dudes on a dig and the weather sucks.”

But why then jump to this random “Indian fetish” that bothers Cthulhu-shadow so much that She has to come pick it up personally? They’re out there looking for fossils, aren’t they? And one of the cooler things about the Cthulhu cult is that it’s pre-human—people have been carving tentacle-gods and worshipping and ravening and so on since the days of the Elder Things. Probably some cone-shaped fossils out there, like I said before—and maybe some of their artifacts too. That would properly strike fear into the souls of Marsh and his men, who want some believable findings to publish and show up That Fool Cope. Or at least strike fear into the souls of his men. Marsh, given his familial background, presumably knows all about this stuff. Of course that doesn’t mean he actually wants to come face-to-face with the Shadow—but note that his reaction is more angry than awestruck.

No wonder he’s so eager to head back to Yale—and to the Atlantic coast, where he can submit his next article to the Annals of the Royal Society of Y’Ha-nthlei, which is proud to report that the fatality rate for their reviewers has dropped for the third decade in a row.

Anne’s Commentary

Given that the ARSY reviewer fatality rate started at 94.6% in the first year of record (1910) and has declined since 1990 to 89.4%, I’m not sure that major self-congratulations are in order. Of course, practically 100% of all human reviewers for the Journal of Nyarlathotepian Studies suffer crippling psychoses, profound paranoia, and unsightly toenail fungus, so nothing to brag about at JNS either, reviewer well-being-wise.

Reading “A Mountain Walked” for the first time, I picked up on its historical fiction vibe without realizing that it was historical fiction, of the real events given a fantastical twist subtype. The vibe, after all, resonated from the story’s very bones, its skeleton, its structure, and how appropriate is that for a tale of paleontologists in peril? Kiernan does narrator Arthur Lakes in the first person “raw,” no polished account but his field journal faithfully transcribed, down to his use of the German Eszett or schaefes S for English double S. Not sure if this is a handwriting affectation of the times or of Lakes in particular, but it adds a touch of quirky authenticity. So do the bracketed notes inserted throughout, as if by an editor of Lakes’ journal. For example, because the journal was a private document, Lakes didn’t write out the full names of people he knew well. For the reader’s assistance, editor adds them, as: “…which set [William Hallow] Reed to the cheerful spinning of many yarns…”

Other clues were anecdotes and details that felt “found” rather than “custom-made.” An example may explain best what I mean. Among the yarns Reed spins by the campfire is one about a deserted camp in North Park where he found a broken fiddle of expert craftsmanship. Rich people must have stopped there, and what happened to them? Run off by Indians? Massacred? That fiddle detail doesn’t seem custom-made for the story, invented. It seems like something Kiernan might have come across in research and used as an unexpected shard of porcelain in her fictive mosaic, the truth stranger—and shinier—than fiction, that can contribute much to both atmosphere and verisimilitude.

Tipped off to the Bone Wars by Ruthanna, I looked into this bloody conflict of the super-collectors, supposing it would make all things murky about “A Mountain Walked” suddenly clear. But my own personal murks remained. So, what IS Mythosian about the story? The title notwithstanding, I’m not getting any Cthulhu-specific vibes here. Or any Deep One vibes, either, sorry, Othniel. Sometimes a Marsh may just be a non-Innsmouth Marsh, I guess, much as I admire Ruthanna’s esprit de corps. The nasty spring with the weird sheen that takes over Quarry 3, now. And that seemed to taint the local wildlife with its oily iridescence! Shades of the Color Out of Space, or one of its many noxious cousins? What about the mountainous shadow in the wilderness, associated with hail, associated with a—companion? avatar?—white as fresh snow, capable at even a remote touch of inflicting severe frostbite? Could that be the Wendigo, Ithaqua? The demon-fetish an image of Itself, worshipped by certain Native Americans as the giver of transcendent agony, feared by the likes of Reed as the same?

Or not, to all the above.

It may be true of all human interactions with Mythos deities (if not ALL deities) that each person’s impression of the Utter Other must be unique. If so, Kiernan wants us to get Arthur Lakes’ impression here, because she chooses him as her narrator rather than Marsh or Reed. Real Lakes wore a whole haberdasher’s shop worth of hats: geologist, artist, mining engineer, writer/journalist, teacher, minister. He was born in England the same year as publication of the book Kiernan has him read aloud to Reed: Robert Chambers’ Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). Dealing with stellar and species evolution, it was popular both with the Radicals and general public; if Lakes was half as fond of nature as Kiernan depicts him, I can see him toting it out to Wyoming as a comfort read. Romantic, yes. Practical. Also yes. Remember all those varied hats he wears.

Of the “uncanny occurrence,” Kiernan’s Lakes writes that he knows Marsh doesn’t want him to write about the event, but he must set it down in his journal for his own memory: “…for all its horror, I cannot wish to forget as it hints at a world even more distant and ultimately impervious to our understanding than the bygone ages and their fauna hinted at by our diggings.” We’re back to wonder and terror, and a man who can accept the close linkage between them! Who can detect the one hiding behind or intertwined with the other. The mountain blocking out the stars is actually just a greater mountain’s shadow. The beautiful snow-pure woman is also insectile, grotesque, wraithlike as a creation of Poe’s. Yet still glorious, like so many aspects of Nature. She, messenger or avatar of the mountain, still of Nature. The mountain, still of Nature. Because Nature is stars as well as species. It’s the cosmos, all.

And so, while Lakes may feel an undeniable dread every night, every night he must look toward the stars.

And what happens after a guy like Marsh dies? Next week, Premee Mohamed’s “The Adventurer’s Wife.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.