In Which Morgoth Pulls Out All the Stops, Fingolfin Goes Fey, Orcs Go Hither and Thither, More Men Show Up, and Húrin Comes Into His Own

This is it, folks. Morgoth has had enough of being quarantined. Sure, he prefers lurking in his basement, what with that blasted Sun soaring across the sky each day. But he’ll be damned if he has to stay cooped up with all his Orcs down there while all those Elves frolic through his forests unmolested. That’s right, his. Remember, Morgoth crowned himself King of the World once. As far as he’s considered, the Children of Ilúvatar are all just squatters.

This chapter also includes many names that might be familiar to The Lord of the Rings fans. Gil-galad, Grond, Easterlings, Sauron, and even that ring that Aragorn wears all play a part here. But fair warning: the body count is about to rise.

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Morgoth – Dark Lord, unfathomable asshole

- Fingolfin – Noldo, incensed High King of the Noldor

- Glaurung – Dragon, biohazard

- Finrod – Noldo, oath-maker, ring-giver

- Barahir – Man, Orc-slayer, ring-bearer

- Húrin – Man, little big brother of Huor, Eagle-rider

- Huor – Man, big little brother of Húrin, Eagle-rider

Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin

Fingolfin, the High King of the Noldor and the fastest sword in the West, hasn’t forgotten Morgoth over these last few centuries. He knows the leaguer that’s kept his foe corralled for all these years ain’t seamless. After all, the Eldar haven’t been able to watch the Dark Lord from the north side, what with those big Iron Mountains there—and that’s how Morgoth’s been able to send out spies and smaller bands of Orcs now and again. Worse, Morgoth has been free to direct his R&D, “devising new evils that none could foretell ere he should reveal them.” Like maybe that Glaurung character…

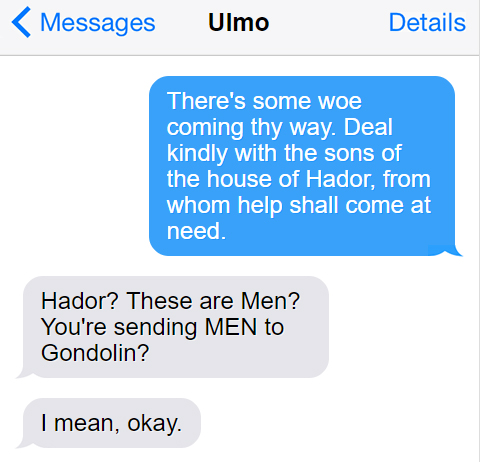

So Fingolfin floats the idea of an actual assault on Angband. The Elves have Men for allies now; they’ve never been stronger. Maybe it’s time to get this done? But one thing he doesn’t seem to have (which has been forewarned a few times elsewhere) is that special intel that there simply is no hope of overthrowing Morgoth, at least not by the Eldar alone. It was first given to Turgon, Fingolfin’s own son, by Ulmo himself. Gondolin would stand “longest of all the realms of the Eldalië…against Melkor.” Meaning they were going to fall.

But Elves are slow to accept change. They don’t really want to make the move that their King suggests. Things seem…pretty good. It’s been nearly four hundred years of peace; why rock the boat by initiating war? They can travel as they please, visit friends, and picnic outside their guarded walls. Sure, there’s a malevolent and primordial evil lurking in the north who wants to kill everyone, but I mean, as long as he’s not running amok with his Orcs, things are okay, right?

The ones least sold on Fingolfin’s crazy idea of assaulting Angband are the sons of Fëanor. I mean, it’s not like anyone took, held, and kept a Silmaril, right? Oh, wait, someone did. Someone hiding behind Angband’s gates. Gosh, for seven Elves who swore to pursue an offending party with vengeance, Maedhros, Maglor, Celegorm, Curufin, Caranthir, Amrod, and Amros sure do spend a lot of time not pursuing folks with vengeance.

In the 455th year of the First Age since the Noldor’s return to Middle-earth, Morgoth at last breaks the leaguer and the long peace like the Kool-Aid Man busting through an unassuming wall. He’s been loooooong preparing for this moment, and he’s got a rather simple and two-pronged approach for Beleriand and everyone in it who’s not a servant of his:

- Rearrange some faces.

- Totally wreck the place “that they had taken and made fair.”

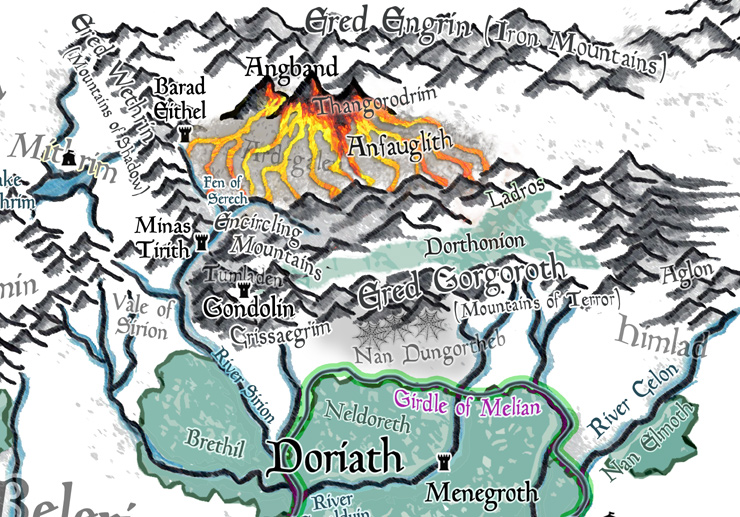

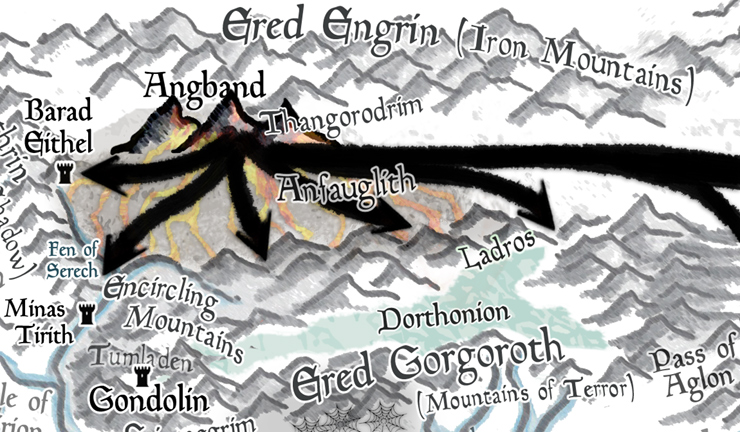

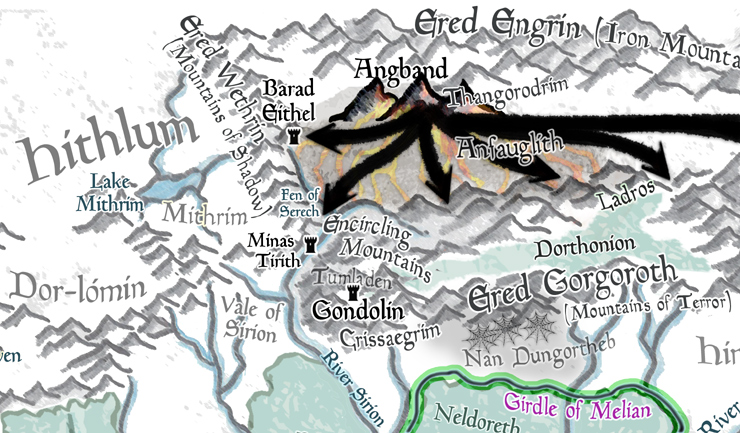

One cool moonless night in winter, Morgoth pulls the trigger, turns all the levers, flips all the switches. Thangorodrim vomits out lava while the Iron Mountains themselves expel stinking fumes into the sky like factory stacks. Everything goes to hell. The lava flows swiftly across the plains of Ard-galen (Morgoth’s very big front lawn), killing everything: the grass, the wildlife, and even the unhappy Noldor on watch in their camps and simply cannot outride these “rivers of flame.” The destruction reaches all the way across the plain to where Ered Wethrin, the Mountains of Shadow, rise to the west and the highlands of Dorthonion rise to the south. The foothills are torched, the trees are blackened, while the Elves and Men standing guard around them are thrown into confusion.

Morgoth pursues what is quite literally a scorched earth policy. Ard-galen itself just…isn’t anymore. Henceforth it will be Anfauglith, the Gasping Dust, a lifeless wasteland. All is ash and dust and fire.

Then:

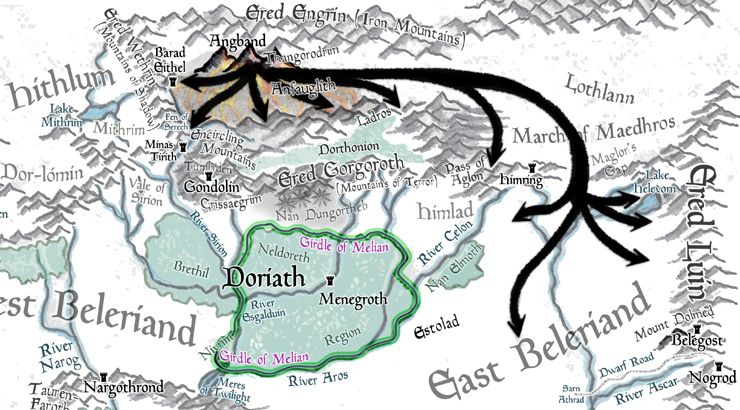

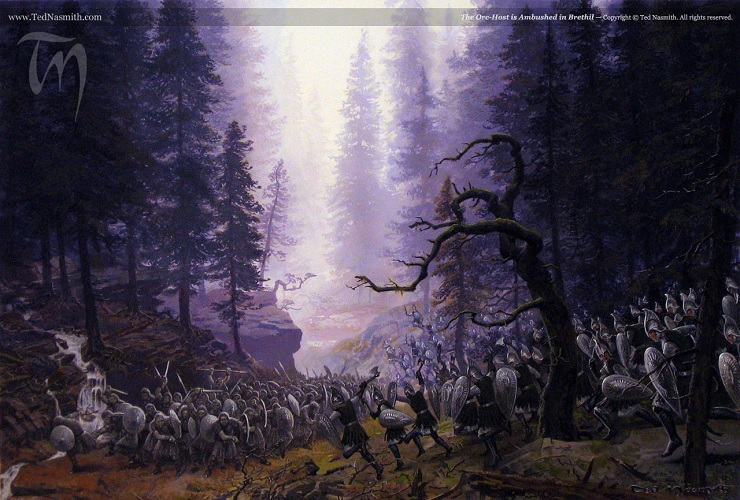

In the front of that fire came Glaurung the golden, father of dragons, in his full might; and in his train were Balrogs, and behind them came the black armies of the Orcs in multitudes such as the Noldor had never before seen or imagined.

Well, shit. Morgoth is at least showing his commitment. He’s not sending out his Orc fodder to test the waters anymore. He’s done testing. These are his big guns in the lead, with the Orc masses following. Right away, these war captains and monsters and their legions head off in every direction and start killing everyone and laying siege to everything. Noldor, Sindar, and Men: anyone in their way gets wrecked; for the most part, only those who flee stay alive.

Although, interestingly, we are explicitly told that had Morgoth waited longer, prepared more fully, and not let his hatred upstage his own judgement, he could have eradicated his enemies completely. But his malice had been bottled up for so long, I guess something had to give. And as devastating as this is going to be, he still underestimates the prowess of the Elves and gives almost no credit to Men. Which he’ll pay for.

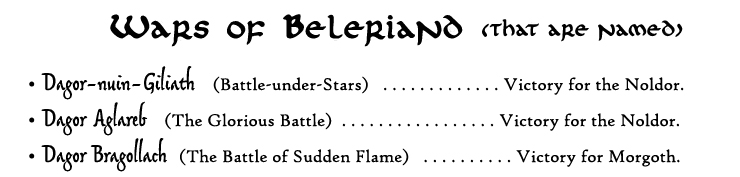

Thus we have the fourth of the Wars of Beleriand. This one is called, quite aptly, the Dagor Bragollach, or Battle of Sudden Flame. The first few days are the worst, as some of “stoutest of the foes of Morgoth” fall, and the many-fronted campaign lasts for just a few months. But this line is worth remembering:

War ceased not wholly ever again in Beleriand.

Which means that whenever things quiet down, it’s just an interlude between more fighting. All these Elf- and Man-occupied realms we’ve been talking about in the last few chapters are going to be cut off from one another quite often; Beleriand’s countryside is just too dangerous now for casual travel. I guess what I’m saying is: if this was a roleplaying game, anyone traveling from point A to point B in Beleriand now has to roll on some random encounter chart to see if they cross paths with an Orc, a war-band, a raiding party, or maybe even an entire army. Never mind the chance of running into Glaurung himself. No longer wet behind the [scaly] ears, he’s a full-grown, big-ass dragon now.

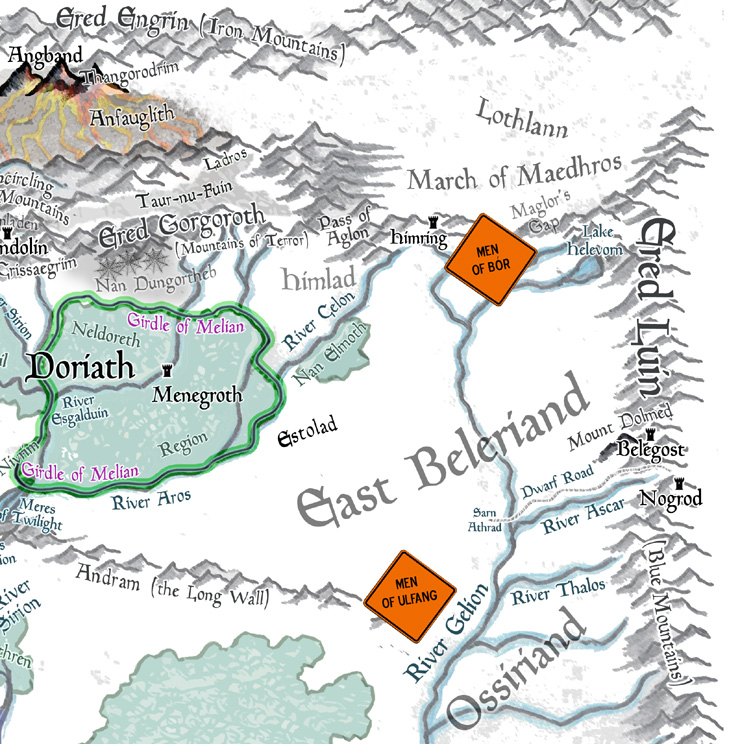

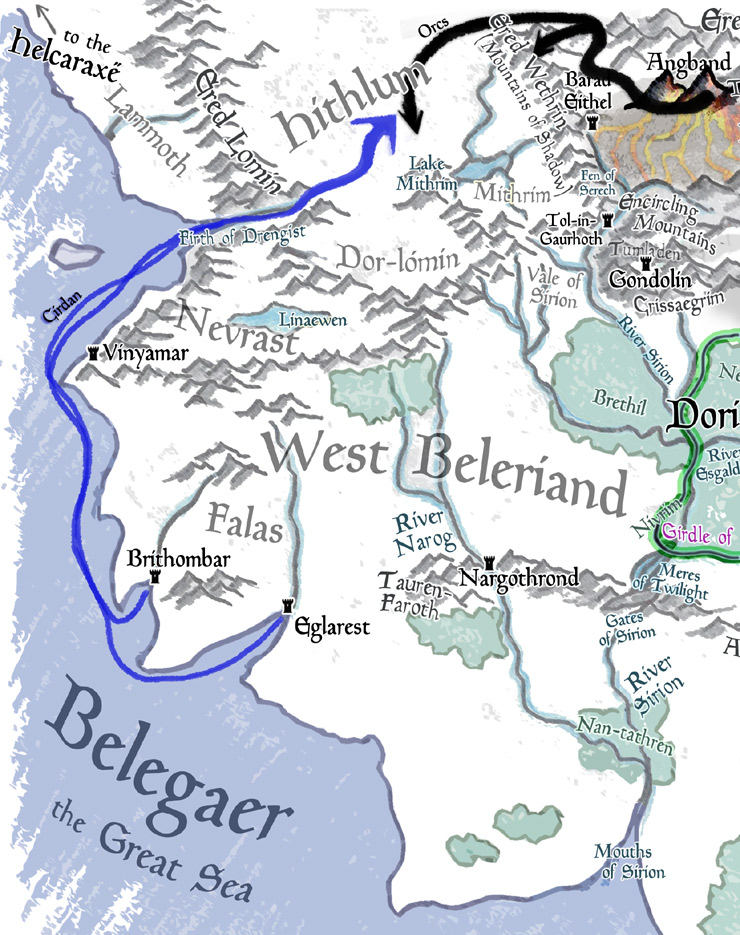

The good guys flee east, west, and south. Mostly south. Doriath, protected by the Girdle of Melian, takes in a lot of the Sindar refugees (remember, no Noldor are allowed in unless they’re kin of Finarfin), while others head to Nargothrond, Círdan’s Havens by the sea, Ossiriand, or other points south.

So this war is initially fought on three fronts, which we can basically categorize by the three royal houses of the Noldor. Let’s start, as Tolkien does, with the Finarfin front.

The Finarfin Front: Dorthonion

Finarfin’s kids, Angrod and Aegnor, are hit the hardest, as their strongholds are right there in Dorthonion, directly across the ruined plains from Angband. Their sister, Galadriel, is safe in Doriath, while their big brother, Finrod, leads a counter strike to the west in the Pass of Sirion. But Angrod and Aegnor are the first Elf-lords to stand up to Morgoth’s forces.

So they’re right in the crosshairs. Morgoth’s armies roll over them.

Men fight and die beside their Eldar friends. The House of Bëor, allied with the now-slain Angrod and Aegnor, is nearly obliterated. But one notable member of the house who isn’t there at this time is Barahir (BAR-ah-here), the great-great-great-great-grandson of Bëor the Old himself. Why? Because he’s off to the west leading the “bravest of his men” around the Fen of Serech, that marshland between the Mountains of Shadow and Dorthonion. There, he comes across Finrod, who’s somehow managed to get himself separated from his Elven warriors and surrounded by a company of Orcs.

And here I want to pause for a second because this is Finrod Felagund we’re talking about, Hewer of Caves (and Sometimes Orcs) and Arda’s coolest Elf. Remember that King Thingol never leaves Doriath (protected by the Girdle) and King Turgon never leaves Gondolin (protected by its secrecy). But King Finrod, who could be safely ensconced in his city of Nargothrond far from the front lines, has instead come right up to the edge of the now desolate and smoky plains. This guy is almost never home, and basically puts all of Beleriand before his own safety. Because Finrod.

Well, this would have been his death—or worse, his capture—to which I think he might have been accepting. “Eh, I had a good run.” After all, a day may come when an Elf is just going to be surrounded by more Orcs than he can slay, and friends who share a bond of fellowship are too far away to help. But it is not this day! This day, Barahir of the House of Bëor shows up with a crew of mortal Men, encircles Finrod with a wall of defensive spears, and then together they “cut their way out of the battle with great loss.” Men lay down their lives for Finrod, and he is saved! The Halls of Mandos will just have to wait.

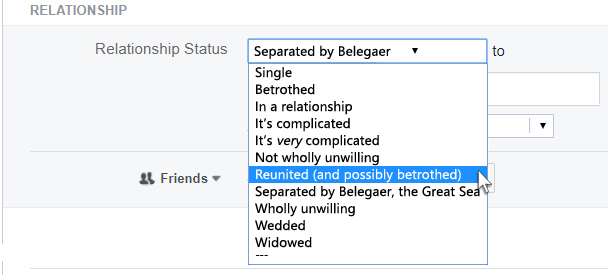

Likewise Amarië, Finrod’s girlfriend back in Valinor, will have to wait a bit longer. It’s bittersweet. They almost got to change their relationship status…

But alas, not yet. Finrod still has work to do. And by the way, remember he was good friends with old Bëor himself, Barahir’s own ancestor. At this point they retreat back to Nargothrond in the south. There, Finrod Felagund swears an “oath of abiding friendship and aid in every need to Barahir and all his kin,” which is like the king of all blank checks on Arda. Finrod Felagund the Chillest Elf That Ever Was owes you a favor?! Wow. He then gives Barahir a very distinctive ring as a token of this oath, one he most likely brought out of the glory of Valinor. Recall now Elrond’s words to Aragorn in “The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen” at the end of The Lord of the Rings at the part when Aragon finds out who he really is:

‘Here is the ring of Barahir,’ he said, ‘the token of our kinship from afar; and here also are the shards of Narsil. With these you may yet do great deeds…’

So yeah, this is the ring Aragorn wears throughout his adventures as a ranger. It is an heirloom that will be passed down for a very long time, even through the hands of the Snowmen of Forochel who are called the Lossoth, and back again to the Dúnedain. Who exactly are these Snowmen? Go read the LotR Appendices if you missed them. They’re cool.

Finrod’s oath, meanwhile, is the oath he himself foreboded some years ago while chatting with Galadriel. It’s the excuse he gave his sister for not settling down with some nice Noldorin girl here on Middle-earth. Barahir, returning to Dorthonion, now rules what little remains of the House of Bëor. But he’s at least got an Elf-king’s solemn oath he can “cash in” at any time.

The Fingolfin Front: Hithlum and the Mountains of Shadow

In Hithlum, High King Fingolfin and his eldest son, Fingon, are hard-pressed indeed at their border, slammed by the forces of evil in their watchtowers. And so are their mortal allies. 66-year-old Hador (of House of Hador fame) is killed defending the the stronghold of Barad Eithel as Fingolfin’s army moves in retreat, leaving his son Galdor to take up the lordship of the house. They all fall back, but at least the Mountains of Shadow prove unassailable to Morgoth’s forces at this time. Which is impressive: there are even Balrogs—that’s plural Balrogs, the worst kind—there at the head of these dark armies, and still “the valour of Men and Elves” keeps all of Hithlum from being taken.

Yeesh, Balrogs. When you imagine the dread inspired by just one of these brutes at a certain bridge of Khazad-dûm, you can appreciate how awesome these Men and Elves were. I am reminded of something Smaug says to Bilbo in The Hobbit:

I laid low the warriors of old and their like is not in the world today.

Considering the time period Smaug must be referring to (his own youth in the Third Age), even those “warriors of old” surely pale in comparison to the Men and Elves in Fingolfin’s army. Moreover these First Age warriors remain a “threat upon the flank of Morgoth’s attack.” Yet to Fingolfin’s deep dismay, Hithlum is also totally cut off from all their allies by a “sea of foes.” It’s all he can do to hold the line on this western front.

Battles are breaking out all over the place at this time. These are the sorts of wars that set The Silmarillion apart from Tolkien’s better-known works. Every pitched battle, unexpected skirmish, or march of armies could easily be the epic climax of its own novel. The first siege of Barad Eithel, where Fingolfin retreats and Hador is slain, might be comparable to the Battle of the Pelennor in scale, valor, and tragic sacrifices—or probably even greater, what with all the Balrogs! Don’t mistake me: the War of the Ring in the Third Age is a huge deal, as it leads to the overthrow of the world’s second Dark Lord, but this is the First Age when the Elves are still numerous and strong; it’s the basis for all those songs and legends that everyone keeps bringing up in The Lord of the Rings. Everyone’s at the top of their game, including the bad guys. It’s glorious and calamitous on a grand scale.

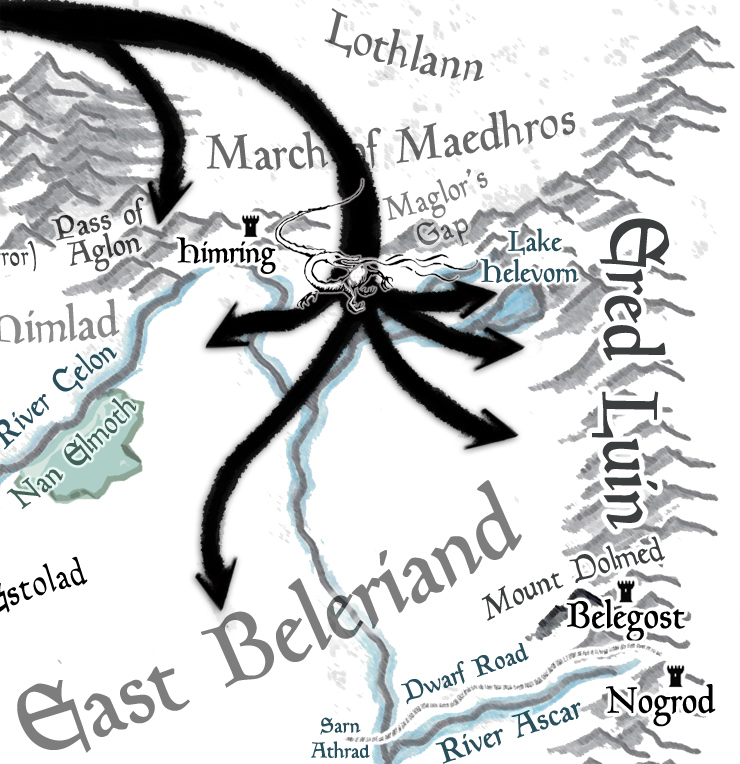

The Fëanorean Front: East Beleriand

With fewer natural barriers between Angband and East Beleriand, the armies of Morgoth have less trouble getting through, and so the lands held by sons of Fëanor are swiftly overrun. The Pass of Aglon is taken, while Glaurung himself comes crawling/slithering through the Gap of Maglor and devastates “all the land between the arms of Gelion.” Dragons of this age—especially Glaurung, their daddy—are like abominable walking blights, polluting the landscape around them. Although Smaug, thousands of years from now, will be nowhere near as gross and slimy as Glaurung, we can see that even in the Third Age, wherever a dragon settles there is desolation. Real estate values plummet and people move out.

We’re specifically told that the Orcs “defile” Helevorn, that great lake in Caranthir’s lands. I don’t even want to know how they do that. I just know that it’s not a place anyone would want to go swimming afterwards. No more picnicking at Lake Helevorn.

So what of the famous seven sons of Fëanor? Not surprisingly, the eldest and “good” M-brothers actually hold the line (though they lose almost everything else). While the others, not doing so well in their lands, skedaddle with their people. In brief:

- Maedhros – Holds the Hill of Himring; kicks serious Orc-ass

- Maglor – Driven out of his Gap but joins Maedhros at the Hill of Himring

- Celegorm – Defeated; flees west to Nargothrond

- Caranthir – Defeated; flees south

- Curufin – Defeated; flees west to Nargothrond

- Amrod – Defeated; flees south

- Amras – Defeated; flees south

But yeah, the now-left-handed eldest son of Fëanor, who once did a stint on the walls of Thangorodrim, proves that he is a force to be reckoned with.

Maedhros did deeds of surpassing valour, and the Orcs fled before his face; for since his torment upon Thangorodrim his spirit burned like a white fire within, and he was as one that returns from the dead.

Essentially, Maedhros embodies the old saying: Whatever doesn’t kill you [by hanging you starved and anguished amid the reeking slag-mountain of Morgoth, for Manwë knows how long] makes you stronger.

Bonus Front: Fingolfin!

Back in Hithlum, Fingolfin completely loses his cool. News reaches him from abroad that his friends and kin are dropping like flies. All his nephews and their lands have been overthrown in the east. Though this might be a bit seemingly exaggerated, it’s nearly all true. Centuries ago, after that first Glorious Battle, Fingolfin had actually boasted that “Morgoth could never again burst from the leaguer of the Eldar.” Yet he has. The High King, despite his vigilance all these years, was still not strong enough to contain the Dark Enemy of the World. And so he despairs. This seems to be the end of the Noldor and perhaps all of Beleriand. Morgoth, slayer of Finwë the first High King, corrupter of the Elves, darkener of Valinor, taker of the Silmarils, has apparently won.

Well, Fingolfin’s not going to take it anymore. Enough Elves and Elf-friends have been killed at Morgoth’s hand; this unlocks for Beleriand a new achievement: Wrath of Fingolfin. A fey-like rage overtakes the Elf-king—though Tolkien doesn’t actually use that word this time, perhaps because Fingolfin’s final sprint feels less impulsive, less mad, than Fëanor’s had. Without consulting anyone, not even his son Fingon, Fingolfin mounts up on his horse, Rochallor, and rides out alone. No one can stop him. Down onto the deathly plain of Anfauglith, he rides all the way to the gate of Angband itself. You’d think Orcs or even Balrogs could be summoned to intercept him, but those who do look upon him flee his wrath. He’s clearly on the warpath—and some even think he might be Oromë the hunter himself, for his “eyes shone like the eyes of the Valar.”

Right up to the big brass doors of Angband he rides, blows on his horn, and slams on the door—just as he did centuries ago when he was fresh off the Helcaraxë and spoiling for a fight. This time he doesn’t turn back, though he’s in way over his head. If the Noldor are doomed to fall, Fingolfin intends to give Morgoth everything he’s got and stick his sword where the Sun surely never shines. He calls out a challenge to Morgoth to face him “in single combat” and his voice echoes down into the depths of Angband because he’s a wrathful Calaquendë and also possibly because Angband has amazing acoustics.

Interestingly, Morgoth doesn’t want to go out and battle Fingolfin, for “alone of the Valar he knew fear.” He’s not exactly at the top of his personal game anymore, and that Elf-king sounds pissed. Not to mention the fact that so much of Morgoth’s might has been spent on marring the entire world and fueling his minions’ strength and malice. It’s like he knows he might not be up to this fight, or at least there’ll be a cost to it. But he also can’t refuse. Fingolfin has called him yellow—well, “craven”—right there at his own doorstep, in front of his captains and servants and slaves. To refuse is to lose face. And Morgoth’s pride is mighty indeed; it has been his defining trait since he screwed with the Music of the Ainur.

Thus Morgoth must answer the challenge. So up he climbs from his bottom-most chamber to the front door, where the son of Finwë is ready for him.

Fingolfin was always the most valiant son of the first King of the Noldor, and he’s basically the mightiest of the mighty, an Elf warrior at the height of his skill armed with an icy blade (Ringil, as it is named, has got to be a +5 weapon!), silvery mail, crystal-studded shield, and a helm. While Morgoth, stepping out at last, is “like a tower, iron-crowned,” holding a huge black lusterless shield and a big-ass hammer, Grond. Some readers may remember this as the name of the massive battering ram wielded by the army of Mordor against the doors of Minas Tirith. From The Return of the King:

Grond they named it, in memory of the Hammer of the Underworld of old. Great beasts drew it, orcs surrounded it, and behind walked mountain-trolls to wield it.

Except this Grond, the original, is wielded one-handed by the original Dark Lord himself. It’s not clear just how huge Morgoth is, but I think we can assume he’s at least as tall as the most monstrous of trolls or any Balrog. The Hammer of the Underworld that he wields might as well be a piece of siege weaponry, given his power.

And then these two combatants get down to business, and it’s possibly the coolest (and as always, tragically brief) fight in the book. Fëanor’s dust-up with Gothmog and the Balrog Brigade might be a close second; hard to say, since the description of that fight is even shorter. Fingolfin’s battle with Morgoth is two evocative paragraphs in length, and that’s a hell of a lot for a book that’s essentially a bunch of synopses crammed together. But every word of this confrontation is worth reading and digesting properly, so I don’t want to bother quoting much here. Do yourself a favor and read it aloud sometime. It’s just amazing.

Fingolfin holds his own against Morgoth; surely no other non-Ainu could last as long. But not only does fighting the Dark Enemy of the World eventually wear him down, every swing of Grond smashes a crater in the ground, making the terrain itself more precarious. Fingolfin wounds Morgoth repeatedly and each of the Vala’s shouts of pain rattles his own minions and sends them falling to the ground, and the cries echo throughout the North. Remember that one cry prompted by Ungoliant? Fingolfin has him crying out seven times.

But then we must come to the fall of Fingolfin, as prophesied by the chapter title itself. With his shield and helm broken, the High King of the Noldor is out of time. Stricken by the Hammer of the Underworld, he hits the ground, and even as Morgoth’s foot is upon his neck, crushing the life from him, Fingolfin gets in one final bloody slash of Ringil as a final eff-you to his enemy. Right in the foot with his ice-blade. Morgoth, who is still confined to his body—strong and nigh invulnerable though it seems to be—is thus hobbled forevermore. If he ever deigned to march out at the head of his own monstrous forces—something he won’t ever do—he’d be limping the whole time, courtesy of Fingolfin.

The Dark Lord lifts up the High King’s body and breaks it further. But before he can toss Fingolfin to the wolves, down from the clouds swoops Thorondor, the King of Eagles, and scratches Morgoth across the face—giving ol’ Melkor a nice little up-yours courtesy of Manwë. This scar, too, Morgoth will bear forever. The great Eagle then swipes Fingolfin’s body and carries it away, far from Thangorodrim, dropping it down on a mountainside overlooking the Hidden City of Gondolin, where his son Turgon finds it.

I’ve heard Corey Olsen, the Tolkien Professor, make an excellent point about this moment. He points out that Thorondor, as agent of Manwë, could have arrived a few minutes earlier and saved Fingolfin, scooped him up and flown him to safety. The Eagles enact the Valar’s moments of eucatastrophe only a few times throughout Arda’s history, but they never rescue anyone against their will. Fingolfin would not have consented to flight. He hadn’t ridden to Morgoth’s door only to retreat again. This was his swan song, a suicidal but valiant last-ditch attempt to smite his foe. Manwë honors Fingolfin’s decision. Thorondor’s after-the-fact intervention merely ensures Morgoth cannot make sport of his body. And bearing the body to Fingolfin’s son, who is currently hidden from Morgoth, ensures he can be most enduringly memorialized.

Turgon, who has not participated in the Battle of Sudden Flame—for the safety of his city is paramount to him and he hadn’t deemed the time right to come forth—is at least able to pay his respects to his father. He builds a cairn for him on a mountain north of Gondolin, looking down on its valley, and the tomb remains a sacred place untouched by Orcs.

This is a serious bummer, and a blow to all the Noldor. At this point, the kingship falls to Fingon. The High King is dead, long live the High King! But with the line of ascension now moving on, Fingon decides to send his own heir away from the front lines. He sends him over to the Havens by the sea. Fingon’s son, by the way, is Gil-galad, who some will remember is precisely one half of the two-person strike team whose efforts in the Last Alliance allow Isildur to cut the One Ring from its master’s hand. So at least it’s nice to meet an Elf, like Galadriel, who we know will live on still for a very long time!

Scattered Elf-friends

Thus Morgoth, who gets to return to his basement throne room, is the hobbled victor. From there he pushes his forces on, and they “overshadowed the North.” Now back from saving Finrod’s butt, Barahir, his son Beren, and the thinned remains of his house at first refuse to leave their lands in Dorthonion, even though the Dark Lord’s power turns the highlands into a haunted and blasted land that gets the name Taur-nu-Fuin, or “Forest under Nightshade.” But it eventually gets so bad there that even Orcs avoid the place unless specifically ordered to go in. Then we briefly meet Barahir’s wife, Emeldir, who quickly joins Haleth (of House of Haleth fame) on the growing list of Women In Tolkien We Totally Want to Spend More Time With But Don’t Get To.

She takes all the women and children that remain of the House of Bëor, arms them, and leads them south and west to safer lands. Emeldir, who we’re told bears the nickname “the Manhearted” (which sounds worse than it’s meant), does this only reluctantly, since her “mind was rather to fight beside her son and her husband than to flee.” Hell yes, I want to know more about Emeldir, who kind of sounds like a Haleth-spirited proto-Éowyn. But in the end she chooses the safety of her people over the need for glory. (And so perhaps “the Womanhearted” would have been equally apt.) But prior to this, she must have had her own battles with the Orcs defending her husband and son.

Her son, Beren, will go on to be instrumental in Middle-earth’s future.

And speaking of, among the people in Emeldir’s care are also two notable young women: Rían and Morwen, future moms of serious import. Someone nicknamed “the Blessed” will come from Rían’s bloodline, while “the bane of Glaurung” will come from Morwen—or so we were told in the previous chapter. Eventually, Emeldir and the women and children in her charge reach the forest of Brethil just outside the Girdle of Melian, where the Haladin (of the House of Haleth) have been living. The group splits here, some staying in Brethil, some eventually moving on toward Dor-lómin in Hithlum. Sadly, Barahir and Beren will never see their wife and mother, nor any of their kin, ever again. In fact, over time Barahir’s crew of “outlaws without hope” are whittled down to a mere twelve who are eagerly sought by Morgoth for their defiance. And still they remain a thorn in Morgoth’s ass.

The Lord of Werewolves

Oh, hey, remember that cat Sauron? You know, the “greatest and most terrible of the servants of Morgoth”? We haven’t heard much about him since his boss’s return to Middle-earth many chapters ago. He used to be in charge of Angband during the big guy’s three-age-long incarceration, and had enjoyed the run of the place. Now he’s had to pack it up and operate elsewhere. Additionally, to the detriment of many, especially the free peoples of the Third Age, he seems to have leveled up a bit.

His skills now include being “foul in wisdom, cruel in strength, misshaping what he touches, and twisting what he rules.” And also, “his dominion was torment” and he seems to bear leadership of werewolves. Congrats on the new job, Sauron!

Now remember, after his rescue by Barahir, Finrod Felagund had retreated back to Nargothrond. Which unfortunately left the river-island of Tol Sirion, where he’d built the watchtower Minas Tirith, ripe for the taking. Finrod had left his little brother, Orodreth, in charge, but when Sauron surges in with his “dark cloud of fear,” a lot of Orcs, and who knows how many wolves, off Orodreth flees. So Sauron seizes the island and tower, paints over the wallpaper and changes the drapes, goths it up big time, and renames it Tol-in-Gaurhoth, the Isle of Werewolves. Sauron sets up shop with his vile wolf kennels and Orcs, and thereby occupies the whole Vale of Sirion region for Morgoth.

By the way, Tolkien’s werewolves are not lycanthropes, i.e. beasts that become men. Instead, they’re essentially the greater and more sentient version of wargs, which are themselves like big wolves inhabited by evil spirits. Werewolves are at the top of that wolvish hierarchy, and bad news for anything made of meat.

It’s worth remembering this place, this Isle of Werewolves. We’re going to come back here in greater detail in the next chapter.

Thralls

Some years go by and the Orcs get bolder and bolder, and Morgoth’s forces seize more and more lands formerly ruled by the Noldor. He starts to take captives, and these Elves are dragged back to Angband and forced into slavery. He puts them to work in his mines (because Noldor are crafty). Now some of these thralls he lets go on purpose, while others do manage to escape on their own (because again, Noldor are crafty). Still “others” are sent out as spies “clad in false forms” to simply look like former slaves. These escapees become a source of mistrust among the non-captive Elves.

But ever the Noldor feared most the treachery of those of their own kin, who had been thralls in Angband

Which is beyond tragic. And this all goes back to the Kinslaying and the curse of Mandos. Once you’ve spilled the blood of your own people, how can you ever trust anyone completely again? So even those of the Eldar who genuinely escape the horrors of the Dark Lord’s prison, work through their shell shock, and retain their own wills still find little welcome back home. (It’s almost as though Tolkien had firsthand experience with the horrors of war, loss, and the difficulty of returning to normalcy again…)

Double-downing on being an asshole, the Dark Lord renews his pro-Morgoth and anti-Noldor propaganda. He sends out messages to the Men of Beleriand—probably not bothering with Barahir & Co.—to say that these hard times have fallen on them all on account of the Eldar. If they would just acknowledge him as “the rightful Lord of Middle-earth,” they’d find honor, not disgrace. To this load of hogwash, most of the Men of the Edain pay no heed. So Morgoth sends his messengers back over the Blue Mountains to the regions east of Beleriand.

Easterlings

And then new groups of Men come over the Blue Mountains, just as the three houses of the Edain had several generations ago. These newcomers are initially regarded as the Swarthy Men—a very generalized term indeed, but they’re also going to go down in history as the Easterlings. Yup, those Easterlings, whose descendants will someday march under Sauron’s banner in the War of the Ring. Now some of these new Men are already secretly on Morgoth’s payroll;

but not all, for the rumour of Beleriand, of its lands and waters, of its wars and riches, went now far and wide, and the wandering feet of Men were ever set westward in those days.

This is a sort of like a second, but less innocent, exodus of Men coming into the West. But as with the three houses of the Edain, they’re not armies on a march to war; they’re whole clans with women and children, too.

Now Maedhros and some of the other sons of Fëanor, who’ve been struggling to hold their lands in the aftermath of the Battle of Sudden Flame, decide to make the best of these new arrivals. More Men are coming? What’re ya gonna do? So they forge alliances with the most powerful Easterling chieftains. One will be named Bór, who signs on with Maedhros and Maglor and leads his mass of people up to their northern reaches. Another is Ulfang, who signs on with Caranthir, and they settle in a bit further to the south.

“Spoiler” Alert: Caring nothing for suspense, Tolkien tells us that Morgoth arranged for some of these alliances, which doesn’t bode well at all. But even though the corresponding betrayals will come later, right up front Tolkien tells us that of these two big chieftains, one’s going to remain faithful to the Eldar (Bór, yay), and one will be false (Ulfang, boo).

In The War of Jewels, Tolkien points out that Bór’s people were also “worthy folk and tillers of the earth,” a reminder that not all of the Swarthy Men are the same. And remember, this is a group of Easterlings who will prove faithful allies of the enemies of Morgoth. I wish, as always, we had more information about them.

Now the Edain eventually come in contact with these Easterlings, and these two groups of Men don’t get along especially well, mostly because they’re strangers to one another and they live far apart. Prejudice is a thing, and Tolkien acknowledges it. “We didn’t hang out together before Beleriand, so why should we start now?” might well be the attitude of their cranky old-timers. In any case, this quality is not entirely unique to Men. It’s not like all Elves considered themselves equal to their brethren. Remember Fëanor’s attitude toward the Teleri, or Eöl’s toward the Noldor, or everyone’s toward the Avari (the Unwilling) far to the east. Remember the Kinslaying. The Firstborn and Secondborn Children, though they are all Ilúvatar’s, are fallible. As are we all.

If anyone had any ideas that Middle-earth is much too black and white, this arrival of the Easterlings in The Silmarillion is another solid reminder that it sure isn’t. It’s a reminder to step back and consider what we are given in the legendarium—which mostly concerns the deeds of Men and Elves and Dwarves and Hobbits in the lands of Beleriand, Eriador, and Rhovanion. Yes, these newcomer men and women who have darker complexions than those earlier men and women are equally as subject to good and evil as everyone else. For every Bereg there’s an Amlach; for every Barahir there’s a Mouth of Sauron; for every Éomer there’s a Gríma Wormtongue; for every Gandalf there’s a Saruman; for every Manwë there’s… Well, no, there’s just the one very, very bad Vala.

Heroes in West Beleriand

Now back to the western/southern front: In Brethil, just outside of the Girdle of Melian, the Men of the Haladin are finally having to deal with the Orcs, whose numbers keep swelling and bringing the war further south, especially now that Sauron has taken over that tower on Tol Sirion. They’ve been able to hold off the Orcs for a while, but now they’re getting hard-pressed. So the chieftain Halmir, whose great-aunt was Lady Haleth herself, sends word of the growing threat to King Thingol.

Doriath’s king has reason to be concerned. Thingol may be grouchy but he’s not the sort of guy who’s just going to wait and let Morgoth wipe out the Noldor. Plus there are tons of Sindar out there in harm’s way. It behooves him to help these Haladin deal with this Orc infestation. So he sends Beleg Strongbow, who as “Chief of the Marchwardens” is essentially Thingol’s border security boss. Beleg (BELL-egg) is going to really shine three chapters from now, but all we need to know about him right now is that he’s a kick-ass warrior of no special bloodline. He’s just a self-made woodland Elf with mad archery skillz. His name means “mighty” or “great” in Sindarin, just as Belegaer is the Great Sea and Belegost means “great city.” Beleg is sort of the Legolas of his time, minus the whole princely schtick. So anyway, Sindar to the rescue! Beleg arrives in Brethil with a great force of Elves who wield goddamned axes instead of swords. Together with the Haladin they surprise the invading Orcs and literally hack up their problem.

Now it’s time to meet Húrin and Huor again, who only got name-dropped in the previous chapter. These two Men are a sort of hybrid of the Houses of Hador and Haleth. They were raised in Brethil among the Haladin since their dad, Galdor, had actually married a Haladin woman and it’s customary in these days to be “fostered” with their uncle’s kin (that is, their Haladin mom’s brother). But when Orcs came into Brethil, these two brothers, who are barely out of their tweens, took up arms. Húrin himself “would not be restrained” from fighting, which means they tried to tell him he was too young. But apparently you’re never too young to hunt some Orc.

Well, during this Orc incursion, Húrin (HOO-rin) and Huor (HOO-or) are with a company of their people who get separated and pursued until only these two boys are left. Wandering alone and seemingly lost by the waters of the River Sirion (still #1 in Ulmo’s Top 10 Rivers of Middle-earth!), they’d have likely fallen prey to roving Orc bands, but a “mist arose from the river and hid them from their enemies.” So now they’re really lost, and who knows where Brethil even is anymore? They end up in the hills at the foot of the Crissaegrim, those mountains that, in “Of Beleriand and Its Realms” we learned was the abode of Eagles…

There Thorondor espied them, and he sent two of his eagles to their aid; and the eagles bore them up and brought them beyond the Encircling Mountains to the secret vale of Tumladen and the hidden city of Gondolin, which no Man yet had seen.

Hoo-boy! Well first of all, yay! The Eagles got involved, but something’s fishy about that. I mean, who commands the Eagles, right? But wait, aren’t rivers and especially the River Sirion more of an Ulmo thing? What’s going on here with the rescue of these two young Men of Hador/Haleth? Perhaps recall this passage from the Ainulindalë, wherein Ulmo is reacting to Ilúvatar’s words…

‘…I will seek Manwë, that he and I may make melodies for ever to thy delight!’ And Manwë and Ulmo have from the beginning been allied, and in all things have served most faithfully the purpose of Ilúvatar.

It sure seems like a little bit of a team-up on their part—to me, anyway. Remember, the Valar are basically hands-off with Men as a race. They let the Noldor quit Valinor, and they’re not going to storm Morgoth’s base, wrecking Beleriand in the process—I mean, not yet. They’re letting the free wills of the peoples of Middle-earth determine their own choices and fates, but that doesn’t mean the Valar are turning their backs to all that’s going on. Up until now the only visible interference in the affairs of Beleriand has been a little swoop-and-rescue action via Air Eagle, and some advice and secrecy via Sirion dreams. But for all we know, there’s a lot more going on entirely behind the scenes that we just don’t read about. The Valar are likely not just twiddling their numinous thumbs back in Aman. No way is Tulkas just reading the paper.

With Húrin and Huor, though, the involvement of Thorondor involves more than mere counsel. This time it’s actual transportation. The Eagles drop the brothers off in the Hidden Valley Ranch of Gondolin itself. Which really is a big deal, considering all the pains Turgon has taken to keep the place secret. But it turns out, he’s cool with it; Ulmo has already given him some kind of hint of their coming from Sirion-based dreams.

So Turgon treats Húrin and Huor well, and they live among the Elves for nearly a year! The splendor of Gondolin would be like nothing they’ve ever imagined roughing it in the woods with the Haladin. In fact, they probably hadn’t spent much time with any Noldor before. It’s mostly the Moriquendi Sindar they had as neighbors. They learn much from the Noldor king and his people, and Turgon in turn becomes really taken by them and wishes they would just live out their short mortal lives here in his city.

And although the two boys eventually feel the desire to return to their people and share in their “wars and griefs,” it’s clear Turgon doesn’t want them to go. But Turgon’s own law—which was “that no stranger, be he Elf or Man, who found the way to the secret kingdom and looked upon the city should ever depart again,” doesn’t quite apply to them. They didn’t find the way in; ginormous birds brought them! Though they certainly weren’t unwilling to be rescued by Thorondor, it hadn’t been their decision to come. Húrin is the one to point this out to Turgon, when the time comes, and also why they cannot stay:

Lord, we are but mortal Men, and unlike the Eldar. They may endure for long years awaiting battle with their enemies in some far distant day; but for us the time is short, and our hope and strength soon wither.

Turgon gets it. He has to let them go. By Eagle, of course, the same way they got in.

But you know who doesn’t care one bit for these two young men, their favor in Turgon’s eyes, and the fact that they get to just leave with no real fuss? Not one tiny bit? Why, Maeglin, of course, the son of Eöl, who was thrown to his death nearly sixty years ago for trying to leave Gondolin. Okay, so that Dark Elf’s death had also been due to the murder of Turgon’s sister and the attempted murder of Maeglin himself. Maeglin, whose resentment at still not ruling Gondolin himself has been simmering as the years go by, says that “the law is become less stern than aforetime.” Bitter much?

Oblivious to all that, Turgon says that he hopes to see Húrin and Huor again “in a little while”—which sure means a different thing to an Elf than to a Man. In the blink of an Elven eye, these two young Men will have beards! Well, after swearing oaths to Turgon about keeping hush-hush, Húrin and Huor are off again by Air Thorondor. The Eagles drop them off in Dor-lómin, taking them to their father’s kin. And while their people are happy to see them alive, they’re astonished that they don’t look like wilderness hobos. Their own father, Galdor, head of the House of Hador, seems dubious about their unwillingness to explain their prolonged absence, or their fine clothing and healthy frames. Still, Galdor is happy to have his sons back and he lets it go. But it doesn’t take long for the other people of their house, who have served with Noldor before, to put two and two together.

And unfortunately, once word goes around that Húrin and Huor have spent time in the company of some very secretive Eldar, it’s only a matter of time before Morgoth hears of it, too. Until now, the Dark Lord knew almost nothing of Gondolin. Now he has a hint. Meanwhile, Turgon still doesn’t think it’s the right time to go sending his own military out.

But he believed also that the ending of the Siege was the beginning of the downfall of the Noldor, unless aid should come; and he sent companies of the Gondolindrim in secret to the mouths of Sirion and the Isle of Balar.

Ah, the Isle of Balar! Remember Ulmo’s island-ferry, the one that brought the Vanyar and Noldor, and then later some of the Teleri over to Valinor? Long, long ago. The Isle of Balar is that piece of island that broke off while Ulmo was moving it; it stayed rooted in the Bay of Balar. Well, this is one of the places Turgon sends his people to build ships (presumably with some local Teleri help). Previously, some of Finrod’s people had come to the Isle to build some forts in case war ever came this far south.

With these ships the Gondolindrim set sail for the “uttermost west” across Belegaer, the Great Sea, seeking Valinor and the pardon of the Valar. This, at least, is one of the Noldor (Turgon) trying to follow through on Ulmo’s old FYI:

But it’s not really the right way. Ulmo had said that one would come to him, to Turgon, when real peril approached Gondolin. Apparently that time isn’t now. And so of the Elf mariners who went sailing “few returned.” Even Morgoth hears the rumor of these would-be messengers, these ocean-going ships who would extend a beseeching hand to the Valar. He is not pleased at this, and he’s especially not pleased that he can locate neither Finrod Felagund nor Turgon, or figure out neither where they’re holed up, nor how strong they are. As someone who’s spent centuries planning and growing his own forces, Morgoth fears the mounting power of hidden Elven realms.

I like to stop and remember that there was a time, back in Valinor after the unchaining of Morgoth—who was just Melkor then—that he mingled with the Noldor, right there in their city of Tirion. In person. Fingolfin, who he brutally slew earlier in this chapter, is someone he once might have exchanged pleasantries with at some Noldorin dinner party once. Or he might have made small talk with Turgon, who he now seeks desperately and out of fear. Sure, Melkor was a seething ball of hatred even then and a total phony, but my point is that these beings kind of know each other in ways that, for example, Aragorn and Sauron never do. Clear enemies from the start, those two, just based on who they are. But the Noldor once listened to Melkor, took counsel with him, learned crafts from him. It’s chilling.

Anyway, now Morgoth recalls the main body of his Orcs to Angband, but he keeps his network of spies quite active. There is a brief if unquiet peace that returns to Beleriand during this time, while the Dark Enemy of the World works to gather “new strength.”

Several years go by and then he sends out a single force against Hithlum, by crossing over the Mountains of Shadow. This time Galdor is slain, and Húrin steps up as the head of the House of Hador. Now Húrin is full grown, “great in strength both of mind and body,” and he leads his own people in retaliation, slaughtering Orcs and chasing them back across the wasteland of what is now Anfauglith.

But more Orcs surge around the mountains from the north right into Hithlum and slam into King Fingon’s outnumbered forces. And that’s when we see the Elf we least expected to see this far north jump onto the scene: Círdan the freakin’ Shipwright! See, he sails up the coastline with a bunch of his people and T-bones the Orcs right there on the plains of Hithlum; scattered, they’re hunted down and slain to the last.

Remember that Círdan’s folk were formerly the Teleri. It’s cool to see Teleri rescuing their Noldor cousins from slaughter. It proves to be a nice little reverse-Kinslaying moment, and shows that there is still hope for the Eldar. Of course, when the Noldor first returned to Middle-earth with Fëanor at the head, they had helped pull the Orcs off Círdan’s Havens, too. Perhaps Círdan remembers this, or perhaps he just knows the Elves need to stick together. Elves before selves. Quid quo pro. I scrape the Orcs off your back, you scrape the Orcs off mine.

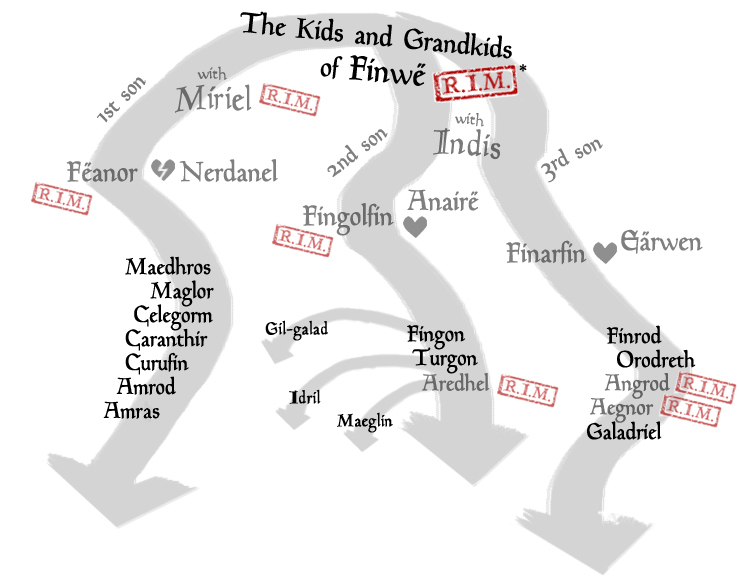

Speaking of Elves, that chart of Finwë’s descendants is getting a little…red.

So the chapter ends with talk of Húrin and how he’s not (unlike seemingly every other Tolkien character) super tall. He’s wiry and lithe; short, but strong and tough as Noldorin nails. He marries Morwen of the House of Bëor, who once lived in Dorthonion before it was totally lost to Morgoth’s assholery.

Which leaves us in just the right spot for the next installment, Chapter 19, “Of Beren and Lúthien,” easily one of the most amazing stories in the book and certainly the most accessible. Finally we’ll learn about the Elf princess to whom Arwen is but a nod. She’s the badass who breaks out of bondage, rescues her own man, and gets all up in Morgoth’s face.

Top image: “Hosts of Angband” by Kenneth Sofia • Sauron “profile” from Bohemian Weasel

Jeff LaSala received the Ring of Barahir (that is, the film replica) from his girlfriend as a counter-engagement ring. Know that when you give someone a token of Finrod’s house as a gift of betrothal, love is evergreen. Tolkien nerdom aside, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He is sometimes on Twitter.