This book. Oh, this book. Horse-crazy tween me loved it with all my heart. I borrowed it from the library over and over, read and reread it. It was the most perfect book I had ever read.

It had everything. Far-away settings. Exciting adventures. Actual real history. Characters I could see and hear in my head. And, of course, horses. Perfect books always had horses.

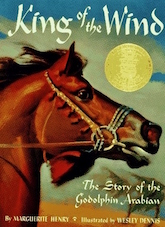

When I embarked on the SFF Equines Summer Reading Adventure, I knew King of the Wind had to be on the top of the list. Somewhat ironically, I never owned a copy. These days I tend to prefer ebooks for ease and convenience and because my book storage runneth over, but in this very special case, I had to have the physical book. That meant the original edition with the Wesley Dennis illustrations and the lovely cover with its head of an Arabian at full gallop, mane and tassels streaming.

Never mind Proust and his madeleines. This book is my Remembrance of Things Past.

When the book arrived, I was almost afraid to open it. We all know what the Suck Fairy does to the beloved stories of our childhood. One written in 1948 (though it didn’t find its way to me until the Sixties) stood all too strong a chance of being, as we say here, of its time.

When the book arrived, I was almost afraid to open it. We all know what the Suck Fairy does to the beloved stories of our childhood. One written in 1948 (though it didn’t find its way to me until the Sixties) stood all too strong a chance of being, as we say here, of its time.

What if it was awful?

Well, thank goodness. It wasn’t awful at all. In fact, I might as well confess, well-post-tween me can’t do much more than fangirl and squee. And maybe I did have a little blurry-page syndrome as I read the story of Agba the Moroccan slave boy and Sham the Arabian stallion.

The subtitle informs us that this is The Story of the Godolphin Arabian. First we get a frame: one of the most famous races of the twentieth century, the match race in 1920 between Man o’ War and Sir Barton. There are thrills, there are reversals, there are last-minute saves—and in the end, despite his less than perfect heritage (one of his great-grandmares was a cart horse), he wins it.

Once he’s won, his owner, Samuel Riddle, decides to retire him to stud. He’s at the peak of his powers and could well have continued his career, but Mr. Riddle has another priority. The greatest achievement of a stallion is his offspring—and Man o’ War is a direct descendant of one of the great racing sires of all time, the Godolphin Arabian, a horse whose pedigree was lost, who could only prove his ancestry through his descendants.

And that’s our entry into the story. It begins at the very beginning, in the stables of the Sultan of Morocco around about 1724, on the last day of Ramadan. Young Agba is one of many stableboys under the Sultan’s master of horse, Signor Achmet, with ten horses under his care. But his favorite is a beautiful bay mare.

She is pregnant and near to foaling, and the Sultan has commanded that just as all humans must fast from dawn to dusk in the holy month, so must his horses. The mare is not doing well. Agba can only hope that with just one more day to go before the fast ends, she can make a recovery and deliver her foal safely.

Finally the long day ends, and Agba can feed and water her. But she has no interest in what he offers. It’s time for her to move to the broodmare stable, where she will be alone because it’s so late in the year and all the other mares have foaled.

And there, while Agba sleeps, she delivers a tiny colt the color of red gold, with a spot of white on his heel, which signifies swiftness. He names the colt Sham, which Henry says means Sun in Arabic (not too far off: actually is Shams). But Signor Achmet discovers another sign, a sign of ill luck: a long whorl on his chest in the shape of an ear of wheat.

Achmet is all set to slaughter the colt for the bad omen, but Agba persuades him to consider the good omen on his heel. That’s a balance, he decides, and lets the colt live.

The colt’s dam is ill and has little milk, and soon dies. Agba half-kills himself to get the foal a sack of camel’s milk from a friendly camel-driver, and with that and wild honey, saves Sham’s life.

Agba becomes Sham’s foster-mother, raises and socializes him since the other foals refuse to accept him, and helps him to grow up strong and swift. Then comes a day when the Sultan summons Signor Achmet and six stableboys including Agba, and gives them a command: the horsemaster will choose six perfect stallions, each of a different color, and each with his own stableboy. They will sail to France as a gift to the king, to whom he writes, “They will strengthen and improve your breed.” Each one will be given a special bag with his pedigree and a set of amulets for luck, which will carried by his personal stableboy.

Agba is determined that one of the stallions, the golden bay, will be Sham. Sham has to pass a test of perfect proportions, and sure enough, he is the most perfect of the Sultan’s bay stallions.

The Sultan has ulterior motives, of course; he wants to curry favor with the young king’s uncle, Monsieur le duc. So does the captain of the ship the Sultan has ordered to transport the horses and their attendants: he skims off their funds for feed and care and delivers them, weak and starving, on the shores of France.

The French are not impressed. These skinny, ragged animals are puny compared to the French horses, and they see no point in breeding any of them to French mares. Five are sent to the army transport corps.

But Sham distinguishes himself by shying at Monsieur le duc’s sneeze and crushing his toe. For that, he is assigned to the king’s chief cook as a cart horse.

Sham is an adequate beast of burden as long as Agba is in charge, but one day the cook insists on taking him to market alone. Sham being Sham, he bolts with the laden cart, sends the cook flying, and gets himself sold in the Horse Fair to a brutal carter.

Agba is desperate to find him. It takes quite some time, and Sham is in terrible condition when Agba finally tracks him down, but Agba offers himself as a servant, and the carter takes him up on it. Agba moves into the carter’s shed with Sham and Sham’s friend, a cat named Grimalkin.

For all Agba’s efforts to feed and care for Sham, come winter, Sham grows progressively weaker. Finally, on a bitter cold day, the carter piles his wagon high with firewood, thinking to make a killing on it. But Sham is too weak to pull the cart far, and on his way up a steep hill, falls and nearly destroys his knees.

The carter beats him half to death, until a passerby saves him: a Quaker gentleman from England named Jethro Coke. Mr. Coke buys Sham and takes him to England with Agba and the cat. Poor old broken-down Sham will make a nice gentle mount for Mr. Coke’s son-in-law, or so he thinks.

Sham, who is all of four years old, slowly regains his strength. Unfortunately, that means that when the idiot son-in-law tries to ride him, he is having no part of it—and he damages the feckless Mr. Riddle rather severely. Mr. Coke regretfully sells him to the owner of the Red Lion Inn as a rent-a-horse.

Mr. Williams is a kind man, but his wife is a bigot who cannot tolerate Agba, “that varmint-in-a-hood!”, or his very opinionated cat. Agba and the cat are banished, and Sham has to survive in the livery stable, where inconsiderate handling and inept riders tax his patience past the breaking point.

Agba tries to sneak back in with the cat to see Sham, is caught, and Mrs. Williams has him hauled off, with cat, to Newgate Gaol. There he languishes for months until a fortunate combination of circumstances brings him to the attention of a beautiful Duchess and her son-in-law, the Earl of Godolphin.

The Earl is a great breeder of horses, and once he learns of Agba’s horse “which he brought all the way from Africa,” he releases Agba from prison and buys the horse. By this time Sham’s pedigree is lost, torn to bits by the warder in Newgate, but the Earl doesn’t care about that.

Godolphin is a haven for Sham and his entourage, and Agba settles in as a stableboy. He soon decides that he hates the king of the stable, a big grey stallion named Hobgoblin. In the meantime, Sham receives little respect from the head groom, Titus Twickerham, and gives none in return.

Then comes a great day. Hobgoblin’s bride is about to arrive, the shining hope of the Earl’s breeding program, the royally bred Lady Roxana.

Agba is sure she must be as coarse and unrefined as Hobgoblin, but the mare who emerges from the horse van is a shimmering white dream. He falls in love—and he cannot bear that this beauty is meant for Hobgoblin. He lets Sham out of his stall, and Sham bolts straight into a screaming stallion fight.

Sham is small but he is lightning fast, and he wins the mare. And that is a disaster. Not for the first time in his life, Agba is banished, and Sham and the cat with him. They’re sent off to a solitary existence in the heart of Wicken Fen.

Agba is sure that the wheat ear of ill-luck has won, and the good luck of Sham’s white spot has run out. But then, after several years, Titus Twickerham appears with the Earl’s red horse van. He has news. The year after the terrible stallion fight, Lady Roxana delivered a colt who was the living image of Sham. The foal who was so narrow and unprepossessing that the Earl, contemptuously, named him Lath. But Lath grew up to be blazingly fast.

Now, finally, someone realizes what Sham is. The Earl wants to build Godolphin’s breeding program around him. Sham returns to find himself installed in Hobgoblin’s old stall, and there’s a new name over the door: THE GODOLPHIN ARABIAN.

Sham and Lady Roxana have a beautiful reunion—and a beautiful foal the next year, named Cade. And the year after that, another, named Regulus. And both of them, like their eldest brother, are blazingly fast.

But all is not well at Godolphin. The Earl is in financial straits. His only hope is to enter Sham’s sons in the Queen’s Plate at Newmarket, with a purse of a thousand guineas.

The Earl not only wants to take the three young horses to Newmarket; he wants Sham to go, too, and be presented to the world as a great sire of racehorses. Then finally Agba can fulfill the promise he made to Sham when he was born: I will be a father to you, Sham, and I will ride you before the multitudes. And they will bow before you, and you will be King of the Wind.

And so it is. Cade and Regulus win their races, and Lath wins the Queen’s Plate and saves Godolphin. Sham is presented to the king and queen.

When the Queen asks what Sham’s lineage is, the Earl replies, “His pedigree has been…has been lost…. His pedigree is written in his sons.”

The English people loved this. Sham’s descendants continued to win races and produce offspring who did the same, until he gained the title of Father of the Turf. When he died at the great age of twenty-nine, the Earl had him buried in his stable under an unmarked slab, because he needed no words to describe his greatness.

And also because Agba had never spoken a word in his life. He was mute. The night Sham died, he returned to Morocco, and was never seen in England again.

Oh my. This book. It’s hard for horsekids now to understand the sheer power the Arabian had before the boom of the Eighties went bust and flooded the market with overbred, brain-fried, conformationally disastrous animals that bore little resemblance to the original horse of the desert—the one that was famous for improving any breed.

This horse was magic. From Morocco to Egypt to Saudi Arabia, breeders had been refining their stock for centuries, and maybe for millennia. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and well into the nineteenth and twentieth, Westerners made great expeditions to the desert to find perfect horses and bring them back to their stud farms. Napoleon rode an Arabian. The Austro-Hungarian Empire bred Arabians with Spanish and eastern European stock to produce the mounts and coach horses of its nobility. Hitler and his Reich stripped eastern Europe of its best horses, including the exquisite Arabians of Poland.

And of course, the king of racehorses, the Thoroughbred, was an Arabian cross, descended from Sham (or Shamsi) and the Byerley Turk and the Darley Arabian and other, less illustrious sires. Marguerite Henry put all of this together into a story of a boy and his horse, and made it come alive with a wealth of detail and a richness of characterization. She did write a perfect book, even to the jaded eye of the longtime writer and editor.

Oh, it pays homage in all sorts of ways and scenes to Black Beauty—notably the scene when Sham falls down pulling the wagon and scars his knees, and is rescued by the kindly passerby. It’s not spot-on accurate about eighteenth-century Morocco (Signor Achmet? Really?), and the details of Sham’s life probably weren’t exactly as she portrayed them. He might not even have been an Arabian; he may have been a Barb, and he may have come from Tunis. He’s said to have had a bad temperament, but spirited, sensitive, intelligent horses, which Arabians are, do not respond well to clumsy handling—and if Sham did indeed have to suffer the life of a cart horse, clumsiness would have been the least of what he had to deal with.

It doesn’t matter.

He was a real horse, who really accomplished what Henry says he did. And he really had a cat. Henry wove a beautiful story around both of them, with a lovely human protagonist (though he is probably fictional)—and not only that. A disabled protagonist.

Agba is really well drawn. His disability is not a tragedy, it’s not inspiration porn. It’s simply there. Sometimes it presents obstacles, as when he can’t speak to save Sham’s pedigree. Most of the time, he just lives with it. That’s a rare achievement, especially for 1948.

Next time, my summer reading adventure will take me to another Marguerite Henry book that means a great deal to me, White Stallion of Lipizza. I hope you’ll come along with me.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent short novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.