V for Vendetta is in the awkward position of being a film that was maligned by its original creator, the incomparable Alan Moore. And while I have deep respect for Moore as a writer, I can’t help but disagree with his criticism of this film.

Especially now. Not after June 12th, 2016—the day a man walked into the Pulse nightclub and opened fire, killing 49 people in Orlando, Florida.

A note before we begin. V for Vendetta is a political tale no matter how you cut it. It is also a tale of great personal importance to me, both for its impact when it came out and in light of recent events. With that in mind, this piece is more political and personal, and I ask that everyone keep that in mind and be respectful.

Alan Moore’s experience with the film adaptations of From Hell and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen had soured him on Hollywood’s reworking of his stories. His complaints about V for Vendetta centered around a few points, the first being that producer Joel Silver had stated in an interview that Moore had met with Lana Wachowski, and was impressed with her ideas for the script. According to Moore, no such meeting took place, and when Warner Brothers refused to retract the statement, Moore broke off his relationship with DC Comics for good. His other irritation had to do with the alteration of his political message; the graphic novel was a dialogue about fascism versus anarchy. The Wachowskis’ script changed the central political themes so that they more directly aligned with the current political climate, making the film more of a direct analog to American politics at the time.

Moore deplored the change to “American neo-liberalism versus American neo-conservativism,” stating that the Wachowskis were too timid to come right out with their political message and set the film in America. He also was aggravated that the British government in the film made no mention of white supremacism, which he felt was important in a portrayal of a fascist government. As a result, he refused his fee and credit, and the cast and crew of the film held press conferences to specifically discuss the changes made to the story. (David Lloyd, the co-creator and artist of the graphic novel, said that he thought the film was good, and that Moore likely would have only been happy with an exact comic-to-film adaptation.)

Two things. To start, Alan Moore’s particular opinions of how art and politics should intersect are his own. I respect them, but I don’t think it’s right to impose them on others. There are many reasons the Wachowskis might have decided not to set the film in the United States—they might have felt it was disrespectful to the story to move it, they might have felt that the analog was too on-the-nose that way. There are endless possibilities. Either way, their relative “timidity” for setting the film in England doesn’t seem relevant when all is said and done. As for the alterations to the narrative, they make the film different from Moore’s tale, of course—which is an incredible story in its own right, and a fascinating commentary on its era—but they work to create their own excellent vision of how these events might unfold. (I also feel the need to point out that though no mentions of racial purity are made, we only see people of color at Larkhill detention centre, which seems a fairly pointed message in terms of white supremacism.) V for Vendetta is a film that has managed to grow more poignant over time, rather than less, which is an achievement in its own right.

In addition, while many of the political machinations may have seemed to apply to American politics at the time, that wasn’t the sole intention of the film. Director James McTeigue was quick in interviews to point out that while the society they depicted had much in common with certain American institutions, they were meant to serve as analogs for anywhere with similar practices—he stated explicitly that while the audience might see Fox News in the Norsefire Party news station BTN, it could easily be Sky News over in the UK, or any other numbers of similarly like-minded venues.

Much of the moral ambiguity inherent in the original version was stripped away, but a great deal of the dialogue was taken verbatim nonetheless, including some of Moore’s best lines. The Wachowskis’s script focused even more on the struggle of the queer population under the Norsefire Party, which was startling to see in a film like this even ten years ago—and still is today, if we’re being frank. Gordon Deitrich, Stephen Fry’s character, is altered entirely into a talk show host who invites Natalie Portman’s Evey to his home under false pretenses at the start of the film—because he has to hide the fact that he is a gay man. The V in this film is a far more romantic figure than the comic makes him out to be, Evey is older, and also pointedly not a sex worker, which is a change that I have always been grateful for (there are plenty of other ways to show how horrible the world is, and the film does just fine at communicating that). You could argue that some of these changes create that Hollywood-ization effect that we so often mourn, but to be fair, giving an audience a crash course in anarchy and how it should oppose fascism—in a story where no one is a definitive hero—would have been a tall order for a two-hour film.

Fans have always been divided on this movie. It has plotholes, sure. It’s flawed, as most movies are. It’s different from its progenitor. But it’s a film that creates divisive opinions precisely because it provokes us. It confronts us. And it does so using the trappings of a very different sort of film, the sort you would normally get from a superhero yarn. The Wachowskis tend to gravitate toward these sorts of heroes, the ones who are super in everything but the basic trappings and the flashy titles. The fact that V has more in common with Zorro or Edmond Dantès than he does with Batman or Thor doesn’t change the alignment. And the fact that V prefers to think of himself as an idea rather than a person speaks very specifically to a precise aspect of superhero mythos—at what point does a truly influential hero go beyond mere mortality? What makes symbols and ideas out of us?

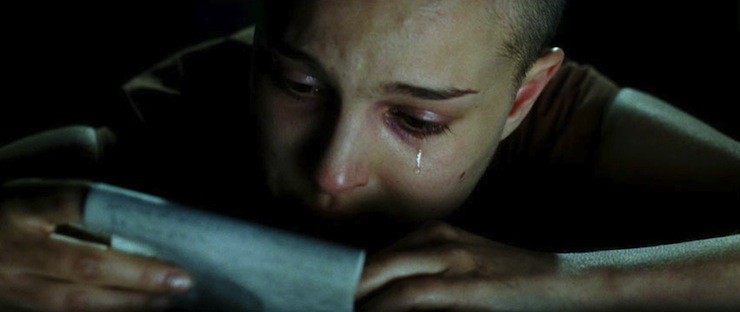

Like all stories that the Wachowskis tackle, the question of rebirth and drawing strength from confidence in one’s own identity is central to the narrative. With V portrayed in a more heroic light, his torture (both physical and psychological) of Evey—where he gets her to believe that she has been imprisoned by the government for her knowledge of his whereabouts—is perhaps easier to forgive despite how horrific his actions are. What he does is wrong from a personal standpoint, but this is not a story about simple transitions and revelations. Essentially, V creates a crucible for someone who is trapped by their own fear—an emotion that we all want liberation from, the most paralyzing of all. Evey is unable to live honestly, to achieve any amount of personal freedom, to break away from a painful past. The entire film is about how fear numbs us, how it turns us against one another, how it leads to despair and self-enslavement.

The possibility of trans themes in V for Vendetta are borne out clearly in Evey and V’s respective transformations. For Evey, a harrowing physical ordeal where she is repeatedly told that she is insignificant and alone leads to an elevation of consciousness. She comes out the other side a completely different person—later telling V that she ran into an old coworker who looked her in the eye and couldn’t recognize her. On V’s side, when Evey tries to remove his mask, he tells her that the flesh underneath that mask, the body that he possesses, is not truly him. While this speaks to V’s desire to move beyond mortal man and embody an idea, it is also true that his body is something that was taken from him, brutalized and used by the people at Larkhill. Having had his physical form reduced to the status of “experiment,” V no longer identifies with his body. More importantly, once he expresses this, Evey never attempts to remove his mask again, respecting his right to appear as he wishes to be seen.

That is the majority of my critical analysis regarding this film. At any other time, I might have gone on at length about its intricacies.

But today is different—the world is different—and I can’t pretend that it is not.

Talking about this film in a removed fashion is a trial for me most days of the week because it occupies a specific place in my life. I saw it before I read the graphic novel, at a time before I had completely come to terms with being queer. And as is true for most people in my position, fear was at the center of that denial. The idea of integrating that identity into my sense of self was alarming; it was alien. I wasn’t sure that I belonged well enough to affirm it, or even that I wanted to. Then I went to see this film, and Evey read Valerie’s letter, the same one that V found in his cell at Larkhill—one that detailed her life as a lesbian before, during, and after the rise of the Norsefire Party. After her lover Ruth is taken away, Valerie is also captured and taken to Larkhill, experimented on, and ultimately dies. Before she completes this testament to her life written out on toilet paper, she says:

It seems strange that my life should end in such a terrible place. But for three years I had roses, and apologized to no one.

I was sobbing and I didn’t know why. I couldn’t stop.

It took time to figure it out. It took time to come to terms with it, to say it out loud, to rid myself of that fear. To talk about it, to write about it, to live it. To watch the country that I live in take baby steps forward, and then huge leaps backward. My marriage is legal, and as I write this it’s Pride Month, the city that I live in is full of love and wants everyone to use whatever bathroom works best for them.

But on June 12th, 2016, as I was preparing to write this essay, an angry man walked into a gay club in Orlando and killed 49 people.

But for three years I had roses, and apologized to no one.

I know why I’m sobbing now. I can’t stop.

And I think about this film and how Roger Allam’s pundit character Lewis Prothero, “The Voice of England,” tears down Muslims and homosexuals in the same hateful breath, about how Gordon Deitrich is murdered not for the uncensored sketch on his show or for being gay, but because he had a copy of the Qur’an in his home. I think about the little girl in the coke-bottle glasses who gets murdered by the police for wearing a mask and spray-painting a wall, and I think about how their country has closed its border to all immigrants.

Then I think about the candidate for President who used Orlando as a reason to say “I told you so.” To turn us against each other. To feel more powerful. To empower others who feel the same way.

And I think about this film, and the erasure of the victims at Larkhill, locked up for any difference than made them a “threat” to the state. Too foreign, too brown, too opinionated, too queer.

Then I think about the fact that my partner was followed down the street a few days after the shooting by a man who was shouting about evil lesbians, and how ungodly people should burn in fires. I think about the rainbow wristband my partner bought in solidarity but decided not to wear—because there are times when it’s better to be safe than it is to stand tall and make yourself a target.

And I think about the fact that this film is for Americans and for everyone, and the fact that it still didn’t contain the themes of the original graphic novel, and I dare you to tell me that it doesn’t matter today. That we don’t need it. That we shouldn’t remember it and learn from it.

We need these reminders, at this exact moment in time: Do not let your leaders make you afraid of your neighbors. Do not be complacent in the demonization of others through inaction. Do not let your fear (of the other, of the past, of being seen) dictate your actions. Find your voice. Act on behalf of those with less power than you. Fight.

And above all, love. Love your neighbors and strangers and people who are different from you in every conceivable way. Love art and mystery and ideas. Remember that it is the only truly triumphant response to hate.

I don’t think I needed a reminder of why this film was important to me, but today… today it hurts even more than the first time I saw it. A visceral reminder of my own revelation, all wrapped up in a tale about a man wearing a Guy Fawkes mask who wanted governments to be afraid of their people, who wanted revenge on anyone who would dare hurt others for being different. A tale of a woman who was reborn with a new capacity for love and a lack of fear, who read Valerie’s last words in a prison cell and gained strength from them:

I hope that the world turns and that things get better. But what I hope most of all is that you understand what I mean when I tell you that even though I do not know you, and even though I may never meet you, laugh with you, cry with you, or kiss you. I love you. With all my heart, I love you.

The most empowering words of all.

This article was originally published in June 2016 as part of the Wachowski Rewatch.

Thank you for this wonderful article. I am not American and live on the other side of the world and sobbed to Valerie’s letter the first time I saw this movie (and many many times after that) much the same and for the same reasons. The message included in this amazing movie is universal and sadly remains fresh and actual as time goes by. Hoping that one day it will truly sound outdated and unnecessary.

Thank you for sharing this.

I clearly need to rewatch the movie, since I don’t remember (and probably completely missed) a lot of the themes. On the other hand, I’m not really up to ugly sobbing. Decisions, decisions.

I’ve never seen this movie but it’s interesting to read about how movies address the issue of Fascism. Yup, we need to remember to respect each other no matter our values/takes on things. I’d certainly rather be respected than tolerated! Toleration is a grudging acceptance and for long grocery lines etc. I am guilty of hiding the “Not One More” part of my wraparound “Not One More” bracelet when I’m at certain places. I have bracelets with specific number of beads divided by smaller beads and on the first crescent moon bead bracelet I made, it begins with has one crescent moon bead for the singer who was killed not long before the people at Pulse, then has five beads because there’s five letters in the word Pulse, then five beads for the NM family who was killed around the same time, then eight for the people killed at the church of Christ congregation in TN, twenty-six for the people killed at the Baptist congregation in TX, and so on, and it’s a wrap around bracelets, and I’ve made more bracelets. And I need to write my Congresspersons yet again, taking the example of the persistent widow in the New Testament parable because maybe if I wear them down, if we all wear them down . . . .

Let’s all fight fascism and conformity by acts of violence and wearing identical masks. Uh-huh.

It’s interesting to consider how much, if any, this essay would have been different if it was written after the trial of the Pulse Shooter’s wife. One of the things that came out during her trial was that the Pulse Shooter was not deliberately targeting gays. The Pulse Nightclub was his third choice; choices one and two had too much security.

In other words, the victims of the Pulse Shooter weren’t shot because of their sexual orientation. They were shot because the Pulse Shooter wanted to kill some people to make a point. This does not change the fact that they were victims, just the reason they were victims.

I’m lucky that my daughter, who occasionally went to Pulse, was not there that evening. It’s probable that she knew some of the victims. They may not have been close friends, but they were still acquaintances.

Ask not for whom the bell tolls…

None of which changes the fact that V is for Vendetta is a fine movie.

Well said.

I disagree with some of the criticisms of the film (and directly with some of Mr Moore’s ownership-of-a-cultural-artifact problems), which are not at all ironic in light of the “nation of setting” objections.

The film has to be set in the UK or quoting the Sex Pistols while wearing a Guy Fawkes mask makes no sense. Indeed, wearing a Guy Fawkes mask makes no sense, and substituting, say, rubber Joe McCarthy masks would be rather too ambiguous, and wooden Daniel Shays masks would make no sense to anyone except scholars of the Articles of Confederation era. In short, keeping it in the UK did far less violence to the original work than would putting it in the US. And ya gotta love someone quoting the Sex Pistols at the checkout counter.

Second, fascism has always been much more overt, much closer to the surface, in England than in the US (which is not a defense of the US’s moral uprightness, just a specific note regarding a specific variety of ick). And it was especially close to the surface during the late Major and early Blair governments in the UK; who can forget all of the Nazi memorabilia parties, the presence of the National Front as a “coherent” political movement (rather than, as in the US, individual members of mainstream parties trending that way), the tabloids, etc.? Perhaps someone who didn’t read any UK newspapers; or know anyone there who was actually engaged in or with electoral politics.

Instead, a US-based counterpart would have had to change the prime rationale for totalitarianism. Instead of the primacy of class, and especially inherited wealth, in the UK (with a strong leavening of anti-immigrant fervor and significant elements of race and religion), one would have been dealing with the primacy of race in the US (with a strong leavening of religion and significant elements of anti-immigrant fervor and class/inherited wealth). This would have been an interesting story, but it would have been more different from Moore’s graphic novel than the particular adaptation of the film.

Third, the particular mechanism of how the High Chancellor comes to and maintains power works only if the underlying government is parliamentary in form. That’s a longstanding theoretical objection to the parliamentary form: That it enables a fleeting majority to have complete control over both legislative and executive functions, thereby planting the seeds for its own misuse. Divided-form governments like the US also have their problems, but they’re different problems and require different means of undermining them.

There’s also a more-subtle aspect of the takeover that is more credible in the UK than in the US. The nonpolicymaking executive branch in the UK is, historically, dominated by that very narrow class of persons who either went to public schools or otherwise “inherited” the impulse to governance (and Orwell himself is an example of this issue) — the very people most predisposed to fascism in general and enthusiastic support of the High Chancellor’s program in particular. In the US — at least since the adoption of Civil Service protections — not so much. In turn, that means that intragovernmental resistance to the High Chancellor’s program would be much more prolonged in the US than in the UK. A change to the US system could be done, but probably not depicted credibly in a two-hour film.

Perhaps that’s the real problem. Perhaps V for Vendetta needed to be a three-night, six-hour television event, or a ten-episode series on HBO or another less-easily-censored distribution system. But that really wasn’t being done on a non-shoestring-budget anywhere in the English-speaking world fifteen years ago, when production was being greenlighted (any more than George R.R. Martin-sized novels were being routinely published in single volumes in the 1960s). Probably the closest analog would have been Berlin Alexanderplatz, and you really know your arts advocacy is in trouble when that’s the closest analog.

@6, regrettably some people are doing exactly that in the US and their definition of ‘fascist’ seems to be ‘anybody whose ideas I don’t like’.

@7, Thank you. Pulse was not an act of hate against gays specifically and it wasn’t motivated by white supremicism.

@9

Which is exactly what is happening in the US currently. There is some control, but only if the majority choose to utilize it. Everything else requires a judicial function, which is extremely slow to act.

Well, the guy swore allegiance to ISIS. If he had even a basic knowledge of ISIS ideology, he SHOULD be a homofob. Though it is true that no one heard him shout any anti-gay slogans.

@9 Small quibble: you’re thinking of the BNP, not the NF. And a bit later than late Major/early Blair (90s).

The NF fell apart in the 80s (though it technically still exists) and the BNP is what emerged from the wreckage. Their first big surge was in 2001; after failing to gain any MPs in 2010 they collapsed and UKIP picked up their vote. So exactly the timeframe of the movie.

I started reading this because it’s one of my favourite movies of all time.

In some ways it’s superior to the graphic novel. I some ways deficient.

But it an amazing movie, and the central vignette of the actress’s life always makes me cry.

And now I’m crying again…

The nonpolicymaking executive branch in the UK is, historically, dominated by that very narrow class of persons who either went to public schools or otherwise “inherited” the impulse to governance (and Orwell himself is an example of this issue) — the very people most predisposed to fascism in general

I’m not sure that this really fits with what we know about the history of fascism. The Nazi Party was not an aristocratic movement; look at its leaders, Hitler, Himmler, Goering and Hess, who all came from fairly modest backgrounds. This article among many others looks at who voted Nazi: http://www.johndclare.net/Weimar6_Geary.htm – “the German Mittelstand (lower middle class) of small businessmen, independent artisans, small shopkeepers and the self-employed, to the threats coming from big business and large retail stores, from the trade unions, the SPD and the KPD, and from increased government interference and taxes to pay for Weimar’s burgeoning welfare state… The lower middle class of Germany’s Protestant towns did constitute the hard-core of Nazi support and were over-represented in the membership of the NSDAP.” Though the Nazis, of course, had plenty of support from the upper-middle class and working class as well.

And back in the 1930s, when there actually was a British Union of Fascists, it wasn’t based among the people you think. Those public-school government types couldn’t stand the BUF; it got nowhere when it tried to set up in Oxford and Cambridge, and any visit by Mosley normally degenerated into violent protests. Though there were some prominent aristocratic fascists, who got a lot of media coverage for themselves, don’t let that fool you: Mosley’s real support base was in the manufacturing areas of the north of England and east London, in particular among Catholics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Fascism

Second, fascism has always been much more overt, much closer to the surface, in England than in the US (which is not a defense of the US’s moral uprightness, just a specific note regarding a specific variety of ick).

I’m not even sure about this either, to be honest. There were uniformed fascist movements in the US in the 1930s, just as there were in the UK – the Silver Legion inspired It Can’t Happen Here, the German American Bund was actually backed by the German Nazi Party. And the KKK held really significant political power in a large part of the US for decades (though it’s arguable whether it counts as fascist, it certainly ticks quite a few of the boxes).

V for Vendetta is in the top 5 list of my favorite comics/graphic novels. It probably cemented my love of anti-heroes and the gritty world that is a vast sea of grey than any other source. And I really liked the movie. I thought the updates/changes were good for bringing the movie out of the Thatcher era it was originally written in to be more appropriate to current times.

I was similarly moved by this movie, and not inclined to view it with a critical eye. What it got right was more powerfully expressed than in any other movie I know of.

I find the film more interesting as a cultural phenomenon than as a piece of entertainment. There is a distinct split between people who adore this film and people who feel quite quesy about it – and while V’s abuse of Evey has made more people fall into the latter category, I’m one of those who would feel a distaste for the film even if those scenes had been cut.

This is an over simplification but I think the split in how audiences react to it comes down to tolerance for political violence – crucially – combined with self-confidence about judging others. If you think V was right to appoint himself as judge, jury an executioner over others – then you are probably going to think of him as a hero and love the film.

But history shows how quickly well intentioned revolts become genocides. If you are familiar with what happened to the Tutsis in Rwanda or the Terrors after the French revolution then the end of V for Vendetta is not a hopeful one.

Added to this is the clear message that brilliant individuals should be allowed to judge rather than institutions or authority (the film deliberately targets religion, courts a and government for criticism)….it’s basically a justification of violent dictatorship.

@19/Line,

Ah, but I highly disapproved of V’s actions while still liking the film.

I am reminded of an article I read in Scientific American in the mid 1980’s about what had been learned about memory from an experiment with Macaques. The article described learning tasks that had been given and findings that had been made while glossing over actual experimental procedures. About halfway through the article I became unaccountably uncomfortable, and decided to begin at the beginning again and read carefully. What I realized then was that the only way they could have learned what they did was by dissecting them. They had ground up about 50 to 55 relatively sentient creatures, simply for the purpose of doing this experiment. I was horrified. Almost I decided not to read any further. Then I reflected that the deed had already been done, nothing would change that now. And I still wanted to know what they had learned about memory.

Similarly with Evey: the deed should not have been done. But now that it was done, what was there to be learned from the experience?

@20/KT

There are even darker real life examples of modern medicine advancing due to non-consensual experimentation on humans – this has also hugely influenced current research ethics committees.

Its a very grey question you raise – the whole breaking eggs to make an omelette thing. In some ways its tragic to not use the omelette as if you don’t then the eggs were broken for no reason.

What worries me is the people who feel justified in themselves breaking the eggs. The people who think that for some reason (master race? intellectual superiority? their just cause?) they are special enough to choose. People like V.

If you follow the line of thinking, you realise that V for Vendetta is not an anti-facist film at all (which is a point more succinctly made by #6 above).

Dostoevsky rejected this view of the “special” case person with Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. I think that V gradually realising that you can get away with what you have done -except for in your own conscience – and realising that rather than being the judge he himself needed grace and forgiveness – would have been a much better end (bit hard to fit into a 2hr film though)

@21/Line,

Perhaps the ending could have been improved by having Evey say to V “I forgive you. But violence can’t be the answer.” Although in that case I don’t know how the movie could have actually ended.

Part of the problem is that the Sutler government is a caricature of a dictatorship, and V is a caricature of a revolutionary. But the interactions between V and Evey were for the most part both real and powerful.

As for those who may have enjoyed the caricatures … When I saw LOTR at the theater, the audience cheered when Gandalf clobbered Denethor. But just about anyone who had read LOTR, and certainly anyone who had read Tolkien’s letters where he discusses Gandalf, would have understood that is exactly what Gandalf cannot do. That kind of willingness to “take over” would mean Gandalf would never have been able to resist the lure of the Ring.

But I wouldn’t want the judge those who enjoyed the “Marvel Comics” aspect of this film too harshly. There is a kid inside all of us that wants to be Superman and the Count of Monte Cristo, is there not?

Ha, well for a story to end there has to be a death or a marriage (or both)- thematically for V the death would still work, it would be great , the given Evey and V’s interactions marriage would have to be a more metaphorical one (V being humble enough to be restored to humanity/God again like Raskolnikov? Therefore for “marrying” the divine/his human condition. Evey makes a decent Sonia stand in if we keep up the Dostoevsky parallel). Actually its there in the film just a little bit when V accepts Surridge’s apology – but that he murders (he would presumably consider it execution) her afterward kills the theme.

Absolutely we enjoy the revenge fantasy – bad decisions make good stories. The Count of Monte Cristo is a good example – an archetypal revenge tale but told in the past without much commentary on the present – hence the lack of discomfort about the message. What’s different about a film like V for Vendetta is that it is less fluffy and is actual trying to be persuasive about the current state of affairs and crucially, what we should do about it.

Nothing wrong with fiction trying to be persuasive per se, its just that I think the message of V for Vendetta is unwholesome. Seems most fans haven’t acted out the message thankfully.

@23/Line,

“Seems most fans haven’t acted out the message thankfully.”

Probably they stubbornly insisted on seeing it as a dark hero/adventure story instead of as allegory like they were supposed to.

I take it that when interpreted metaphorically “death or marriage” can encompass a great many things, but I’m still trying to wrap my head around the idea that covers them all. I wanted to offer the counterexample of Sam returning home at the end of LOTR and saying simply “Well, I’m back” – except it’s true, he did get married.

I have read Crime and Punishment but all I can recall is Rashkolnikov murdering an old woman with an axe and continuing to descend into some personal hell. Problem was I didn’t find it even remotely convincing. It’s considered a great work of fiction, so maybe it was just over my head.

In more practical terms, the problem with trying to end a story like V is: how are you going to continue to live under a dictatorship? Do you find a way to go into hiding? Do you join a resistance movement where you find nice people to have tea with and complain? Or do you actually kill the King and end up with Robespierre, or kill the Czar and end up with Stalin, or kill Julius Caesar and end up with Augustus Caesar, etc? It’s an interesting question whether you can solve the problem by cutting off the head of the snake, or whether the problem of dictatorship can only be solved by gradually changing the nature of a society that allowed it to happen. Still, given an opportunity to kill Der Fuhrer, I’m probably going to take the shot and hope for the best.

I liked that you pointed out that whatever rationalizations V finds for his actions, he’s still going to have to live with his own conscience. And that’s likely to be painful. Was that perhaps the message of Doestevsky? I just don’t recall it that well.

On the one hand, I totally agree with you about the prison scene and the letter. I’m a lifelong, hardcore comics geek (I think I have something like 25 thousand of them), and Valerie’s story is, IMO, the best single issue of any comic ever. It was what led to me pushing V for Vendetta at people and telling them to read it.

I was, honestly, terrified of seeing the movie because I was *sure* they were going to screw up that scene, and I was astonished that they didn’t. It’s beautiful, it’s meaningful, and it’s as important today as it was when it was originally written.

That said, I think you brush past Moore’s objections a little too easily. Yes, he’s being too picky (he always is — this is a man defined by picky), but his core point is right: they changed the fundamental *message* of the story, and not for the better. That’s not a matter of needing more time to talk about politics — it’s that the movie deliberately changed the other two most important scenes in the story, in ways that largely reverse their meaning.

The subtlest but most important difference is V’s speech to the nation. In the book, this is a radical and *accusatory* call to action: a statement to the people that this is *their own collective fault*, for allowing it to happen. The book states, pretty strongly, that if you don’t fight fascism with your breath and body and soul, you’re allowing it to happen. In his speech, V quite overtly blames the populace for the horrors of their leaders, saying that those leaders, and thus their actions, were the peoples’ responsibility.

By contrast, in the movie V basically says, “The bad guys did this to you, and I’m going to stop them”. It removes that sense of collective and individual responsibility, and simply turns it into a matter of the good little guys vs. the evil big guys. In this, the movie is much more stereotypically “comic-book-y” than the book is.

I’m not surprised that the Wachowskis made the changes they did — the book’s inevitable conclusion is *not* an easy happy ending, and it would have been a much harder sell to the movie-watching audience. But by changing the speech, and changing the ending, they took a book that was *intensely* anti-authoritarian, and made it — well, a little authoritarian. In the movie, the people are saved by V and Evie — moreover, they *need* to be saved, and their salvation is through obediently falling in line with the good guys. (I found the masks scene at the end of the movie *disturbingly* creepy.)

So yeah, Moore was pissed off by that. Really, so was I. My disappointment was sharp, because they came *so close* to making the perfect adaptation of the greatest of all graphic novels. They just missed the point of what the novel was about.

Yes, the movie is still important; yes, the story of Valerie is still as heartbreaking and beautiful as it was then. But the book — with its message that it is everyone’s responsibility to actually stand up and fight the rising tide of authoritarianism by thinking and acting yourself — is even more important today, in an age where far too many people are cheering the fascists on…

Yeah LOTR is a good example, one of the reasons the book and the film seem to “end more than once” is that there are two literal marriages and a metaphorical death. I strongly suspect that an editor today would insist the book ended with Aaragorn and Arwen’s wedding and made Tolkien write the last few chapters as a spin-off.

Death and Marriage can indeed be represented in an broad spectrum of ways. Some good examples of non-literal ones would be Shawshank Redemption – with the “marriage” of Red and Andy meeting each other on the outside, or Requiem For a Dream which has the metaphorical death in the title.

Crime and Punishment has multiple themes in it to the extent that any claim of the message would likely get me in the middle of an ongoing literary and psychological debate, but one of the themes is that “punishment is not just legal consequences. For Raskolnikov the punishment his own conscience gives him is far worse than the law as he gradually recognises what he has done. The story ends with a “marriage” though as Raskolnikov (who’s name is a pun on “split”) confesses and rejoins humanity and faith.

How do you peacefully remove a dictatorship is an interesting question. In history it seems to be achieved (relatively) peacefully over multiple generations and often involves the forming of trade unions and other collectives in order to wrestle power away from the aristocracy over time. So not an easy option for a film. Perhaps V for Vendetta could have continued with a sequel in which a Stalin/Pol Pot figure claiming to be the continuation of V’s revolution was torturing all the former elites and running show trials to discredit and demonise his enemies would satisfy brevity and responsibility. You could even have V’s corpse preserved like Lenin’s.

I think you hit the nail on the head there, if its just dark fantasy then its just entertainment. Its the idea this story is something more that I dislike

The book states, pretty strongly, that if you don’t fight fascism with your breath and body and soul, you’re allowing it to happen. In his speech, V quite overtly blames the populace for the horrors of their leaders, saying that those leaders, and thus their actions, were the peoples’ responsibility.

By contrast, in the movie V basically says, “The bad guys did this to you, and I’m going to stop them”. It removes that sense of collective and individual responsibility

The speech in the film makes the same point as in the book. V tells the British people: “And the truth is, there is something terribly wrong with this country, isn’t there? Cruelty and injustice, intolerance and oppression. And where once you had the freedom to object, to think and speak as you saw fit, you now have censors and systems of surveillance coercing your conformity and soliciting your submission. How did this happen? Who’s to blame? Well, certainly there are those more responsible than others, and they will be held accountable, but again, truth be told, if you’re looking for the guilty, you need only look into a mirror. I know why you did it. I know you were afraid. Who wouldn’t be? War, terror, disease. There were a myriad of problems which conspired to corrupt your reason and rob you of your common sense. Fear got the best of you, and in your panic you turned to the now high chancellor, Adam Sutler. He promised you order, he promised you peace, and all he demanded in return was your silent, obedient consent…”

So he isn’t entirely letting them off the hook – though I admit that it’s toned down slightly from the book version.

How do you peacefully remove a dictatorship is an interesting question. In history it seems to be achieved (relatively) peacefully over multiple generations and often involves the forming of trade unions and other collectives in order to wrestle power away from the aristocracy over time. So not an easy option for a film.

On the other hand, look at 1989. That was a sudden process; peaceful in some countries, less so in others. Look at 1986 in the Philippines.

@23 To be fair, V doesn’t kill Surridge after accepting her apology: he has _already_ poisoned her. On the other hand, he obviously makes no attempt to save her and shows no regret. (Of course, she accepts her death as deserved, if not welcome.)

This film has been hitting me in the gut so long now. I’ve never managed to get through a watching without crying repeatedly and I’m glad I didn’t get to see it in the cinema (my local didn’t show it, because reasons, apparently) because when I put the DVD on the first time, I had to repeatedly pause it. It was literally too much.

It was too much because where I lived, I was basically living in this film. The Norsefire party was basically my local council, at least the mindset was the same if not the level of surveilance. Those are the attitudes I grew up around though: the veiled but very present facism and homophobia; hatred and intolerance prettified as ‘what the people want’ and ‘moral decency’. Fascist filled pubs on almost every corner (literally three within spitting distance of my parents house that displayed a Nazi swastika somewhere) and being physically assaulted for the mere suspicion of being gay.

So no, this film was not about America. Not in any way at all!

It may be a somewhat Americanised version of England, but it is very much an English film, and yes, it is still so very relevant.

I also encountered this film before the comic, though I think this was the best way to do it. I do not think I would have appreciated the film in the same way had I read the comic first, but seeing the film first did not stop me appreciating the comic. They are different, but they are both valid and equally terrifying in their implications.

I, too, explored my queer identity with this film. Your words are perfect. I watch this film every year for the 5th of November. I wish all of America did too. It still feels so necessary.

Is it not hypocritical that comments must be approved by tor? Is it not possible that the “inspection/filter” could be, in any way abused? Do you have no shame implementing it for this article?

what a very well written article. I love this film, Natalie Portman is amazing in it and I am so glad it got made. It doesn’t matter where or when it is set, it’s an analogy for many regimes and countries over time, and I agree it remains relevant. I think it should probably be shown to over 15s in schools. Intolerance has no place in society

Hey there friend,

It is August 4, 2019, and V is still very relevant and poignant. I’m re-reading it for a book club and thinking about how realistic the events of V’s world feel today. It honestly doesn’t feel that far off. How incredibly sad is that? Yesterday the El Paso shooting happened, and I am left, yet again, completely dumbfounded as to how human beings can do this to one another. Thank you for your article and for sowing hope. I needed to hear these words. In kind, I see you and I love you. Let’s continue to show love to this world, though it sometimes doesn’t deserve it. It is because of people like you that I still uphold a sliver of belief that change can happen.

Thank you kindly, and keep your head up.

It’s 14th April 2020. The world is fighting a mysterious virus, and a fear fueled by media is already spread worldwide. Moreover I have read today, that more than a dozen of governments have taken the advantage of the situation by introducing more intrusive surveilance methods, collecting data, taking away civil liberties. Alan Moore has almost forseen the future.