Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

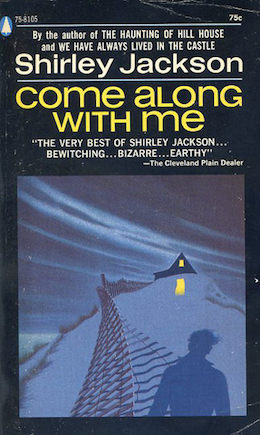

Today we’re reading Shirley Jackson’s “The Summer People,” first published in 1948 in Come Along With Me. Spoilers ahead.

“I’d hate to leave myself,” Mr. Babcock said, after deliberation, and both he and Mrs. Allison smiled. “but I never heard of anyone ever staying out at the lake after Labor Day before.”

Summary

The Allisons’ country cottage stands on a grassy hill above a lake, seven miles from the nearest town. For seventeen summers now, Janet and Robert have happily endured its primitive accommodations—well water to be pumped, no electricity, that (for the neophyte city sojourner) unspeakable outhouse—for the sake of its rustic charms. And the locals are great people! The ones they’re acquainted with, you know, the tradespeople in the town, “so solid, and so reasonable, and so honest.” Take Mr. Babcock, the grocer. He could model for a statue of Daniel Webster, not that he has Webster’s wit. Sad how the Yankee stock’s degenerated, mentally. It’s inbreeding, Robert says. That, and the bad land.

Like all the other summer people, they’ve always gone back to New York right after Labor Day. Yet every year since their children have grown, they’ve wondered why they rush. September and early October must be so beautiful in the country. Why not linger this year?

On their weekly shopping trip to town, Janet spreads the word she and Robert will be staying on at the lake. The merchants are laconically amazed, from Mr. Babcock the grocer and old Charley Walpole at the general store, from Mrs. Martin at the newspaper and sandwich shop to Mr. Hall, who sells the Allisons butter and eggs. Nobody’s stayed out to the lake past Labor Day before, they all say. Nope, Labor Day’s when they usually leave.

Not exactly an enthusiastic oh, stay as long as you like, but Yankee dourness can’t compete with the seductions of lake and grass and soft wind. The Allisons return to their cottage, well pleased with their decision.

Their satisfaction wanes over the next few days as difficulties arise. The man who delivers kerosene—Janet can’t remember his name—says he doesn’t deliver after Labor Day. Won’t get another delivery of oil himself until November. Didn’t expect anyone would be staying on at the lake, after all. The mail is getting irregular. Robert frets at how tardy their adult kids Jerry and Anne are with their weekly letters. The crank phone seems crankier than ever. And now Mr. Babcock can’t deliver groceries anymore. He’s only got a boy delivering summers. Boy’s gone back to school now. Oh, and as for butter and eggs? Mr. Hall’s gone upstate for a visit, won’t have none for you for a while.

So Robert will have to drive to town to get kerosene and groceries. But the car won’t start. His attempts to ring the filling station are fruitless, so he goes for the mail, leaving Janet to pare apples and watch for dark clouds in a serene blue sky; it’s in herself she feels the tension that precedes a thunderstorm. Robert returns with a cheerful letter from son Jerry, but the unusual number of dirty fingerprints on the envelope disturbs Janet. When Robert tries to call the filling station again, the phone’s dead.

By four in the afternoon, genuine clouds turn day dark as evening. Lightning occasionally flashes but the rain delays, as if lovingly drawing out the moments before it breaks on the cottage. Inside Janet and Robert sit close together, their faces illuminated only by lightning and the dial of a battery-powered radio they brought from New York. Its city dance band and announcers sound through the flimsy walls of the summer cottage and echo back into it, “as though the lake and the hills and the trees were returning it unwanted.”

Should they do anything? Janet wonders.

Just wait, Robert thinks. The car was tampered with, he adds. Even he could see that.

And the phone wires, Janet says. She supposes they were cut.

Robert imagines so.

The dance music segues into a news broadcast, and a rich voice tells them about events that only touch them now through the fading batteries of the radio, “almost as though they still belonged, however tenuously, to the rest of the world.”

What’s Cyclopean: This week’s language is sober and methodical, like Mr. Walpole’s package-tying.

The Degenerate Dutch: Physically Mr. Babcock could model for Daniel Webster, but mentally… it’s horrible to think how old New England Yankee stock has degenerated. Generations of inbreeding, that’s what does it.

Mythos Making: Step outside the neat boundaries of your civilized world, and you’re going to regret it. Especially in rural New England.

Libronomicon: The Allisons’ son sends a letter… unless he doesn’t. Something about it doesn’t seem… quite… right.

Madness Takes Its Toll: See above; Mrs. Allison comments rather dismissively about Mr. Babcock’s mental state. That he might not be feeling entirely cooperative with a couple of Summer People never does occur to her.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Buy the Book

Deep Roots

First, I have a confession to make, as a now-expatriate native of a Cape Cod tourist town: this is totally what happens to people who fail to cross the Sagamore Bridge in an orderly fashion by Labor Day.

I assume so, at least. I haven’t been back for a while; I’ll have to ask my folks what everyone decided at the last town meeting.

There’s horror on both sides of the weird symbiosis/hate relationship between host community and temporary visitors. This place you visit, where half the population is people like you and the other half are trying not to lose their tempers from the other side of the overcrowded fried clams counter—what mysteries do they perform on the deserted beach after you go home? Those Summer People, wafting in from parts unknown to rearrange your world and turn all ordinary rules of conduct upside down—what secret plans and cunning arts do they practice after they return underhill?

We’re not always good at welcoming, are we? Sometimes we’re not so comfortable being welcomed, either. Even—especially—when Locals depend on Visitors’ gifts to keep their community thriving, we suspect resentment hiding behind those masks. And all too often we’re right. But the tourist/town relationship is ephemeral. Everyone involved knows it will blow away as vacation season ends—so the fear and resentment and mystery can afford to remain unspoken. Unless you’re Shirley Jackson.

Jackson’s Lake Country distills all this anxiety into a sort of inverse fairyland/Brigadoon. Stay past dawn/Labor Day, and you’ll never return to ordinary life. But this isn’t the simple narrative, either, of being forced to stay in the world where you tarried too long. Instead the town’s welcome, its services, even your ability to travel to and fro vanish out from under you. Never say you weren’t warned. And never mistake those warnings for simple Country Manners.

And then… Jackson doesn’t need to complete the circle. She doesn’t even need to provide a clear implication about what happens next. All we need to understand is that it’s bad. Worse than an Autumn without heat or cooking oil, worse than a sabotaged car or cut phone line.

In much of horror, Lovecraft included, even a short visit to a rural New England community is fraught with peril. Plan a day trip and you could get stranded in a cursed house, or be subjected to an unpleasant monologue from a cannibal who won’t shut up. A longer stay may teach you more about local genealogy than you wanted to know—or more about your own. “Summer People” is definitely more on the “gambrel” side of fearful communities than the “cyclopean” side, and heading towards the unexplored-by-Lovecraft “I guess it has a roof” end of the spectrum. Different sorts of residents, and different sorts of fear, lie behind all these diverse facades.

Different types of vulnerability, too. Lovecraft’s protagonists are often drawn by curiosity, the desire to learn what’s behind a community’s mask. Poor Mr. and Mrs. Allison, though, never even suspected there was a mask. Out of all the motivations leading to all the bad ends in all of horror, the simple desire to look out over a beautiful lake seems particularly distressing. It’s one thing if you really, really, wanted to seek out Things Man Was Not Meant To Know and copy out passages of the Necronomicon. It’s another if all you want is to join the landscape and community that you’ve come to love.

Anne’s Commentary

Buy the Book

Fathomless

Oh yes. Anyone who has lived in a community with a tourist-driven economy will recognize this uneasy dynamic: We need you to come and spend, and you come and spend, and so we love you. Until you realize we need you to come and spend, and expect subservient gratitude along with service. And then we hate you. The dynamic grows uneasier still in a community that depends more heavily on seasonal residents—people who own property in the community but occupy it only occasionally, when the weather’s nicest. People richer than us. People more sophisticated than us. People more important than us. People who know it, too, don’t be fooled by their condescending talk about us being the salt-of-the-earth. They don’t use salt-of-the-earth. Only the finest turquoise-flecked sea salt from Fiji is good enough for them!

It’s Otherdom based on class, on one’s place in the economic pecking order, on one’s social prestige. Factors like race and gender certainly enter into these complex equations, but they need not. I think it’s reasonably safe to assume that all the characters in Jackson’s story are white, but the Allisons dwell on a hilltop in more than the literal sense. Not only can they afford that hilltop over that lake, they can afford an apartment in New York City! Their normal lives must be awfully soft for them to enjoy roughing it in the cottage during the easy summer months! They must think themselves pretty woke for their era, not yelling at the delicate country bumpkins the way they can yell at the tough city help and allowing that they’re fine physical specimens, even if inbreeding has weakened their wits.

You know who else dwelt on a hilltop? HPL, that’s who. Back in the day, when the Phillips were quite well-to-do, thanks. That wealth didn’t endure into his adulthood, but there may be no gentility that shrinks from the lower classes with more visceral shuddering than genteel poverty. The mongrels of the Providence waterfront and Red Hook were bad, very bad. A little less so, perhaps, were the Italians on Federal Hill. But not to be let off were the indisputably Caucasian denizens of so many rural locales in Lovecraft’s fiction. I doubt he’d have joined Janet Allison in her praise of countryfolk, for he wrote: “The true epicure in the terrible esteems most of all the ancient, lonely farmhouses of backwoods New England; for there the dark elements of strength, solitude, grotesqueness, and ignorance combine to form the perfection of the hideous.”

That’s from “The Picture in the House,” whose fiendish bumpkin is a carnivorous old man, or I should say anthropophagous. Dunwich hosts a fine nest of backwoods degenerates, of course, though the porous landscape around the Martense manse might harbor even worse. I’d like to suggest that when the storm breaks over Jackson’s cottage, lightning will open a fissure beneath it, and white ape-like mutants will swarm out and drag Jackson’s summer people to gnashing doom in the fetid earth of their tunnelings.

Jackson would never do that, though. However, she might allow the town merchants to ring the cottage with knives drawn, ready to filet these pesky city people for the Beast of the Lake, even as It rises swaying and ululating in strange blue-green lightning flashes.

No?

Yeah, no.

Jackson is going to let us imagine what ends this particular battle in the class wars. I think it’s going to be terrible when the radio batteries die, and the Allisons hear the concussion of heavy rain on the roof, or fists at the door, or both.

Next week, Mariana Enriquez’s “Under the Black Water” looks at what horrors really taint a river. Translated into English, you can find it in her Things We Lost in the Fire collection.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 10th, 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.