When Paper Girls debuted in the halcyon days of 2015, it was justly well received, earning high praise from reviewers, a Hugo nomination for best Graphic Story, and a couple of Eisner awards. However, a lot of the praise for the first volume was based on promise. The story of four 12-year-old paper delivery girls in 1988 caught in the crossfire of a temporal war threw a lot of balls into the air—enough that it made sense to question whether writer Brian K. Vaughan, illustrator Cliff Chiang, colorist Matthew Wilson, and letterer and designer Jared K. Fletcher would be able to catch them all.

Three years, twenty-two issues, and four volumes later, I’m happy to report that they caught them with aplomb, while deftly throwing in two more balls, an apple, and a chainsaw. (End juggling metaphor.)

Because of its mystery box nature, where weird shit happens with only the promise of an eventual explanation, the series has taken its time to reveal its characters, setting, themes, even its general structure, but with Volume 3—nominated for this year’s Best Graphic Story Hugo—a pattern emerges: each volume collects five issues, focuses on one of the four main protagonists (Erin, KJ, Tiffany, and Mac) and ends with the girls bounced into a new era: so far the prehistoric past, the far future, and the terrifying years of 2016 and 2000.

We learn more about the conflict the girls are navigating between the Old-Timers, dinosaur riding techno-knights dedicated to preserving the time stream, and the teenage Rebels, rag-wrapped scavengers who believe history can and should be changed.

And we learn more about the girls themselves: Erin, the new girl, just wants real friends; Mac, a foul-mouthed tomboy, uses her tough exterior to hide her existential fear; Tiffany, nerd and proto-feminist, is desperate to rebel against her parents, and, KJ, an impulsive field hockey player, deals with inner passions and discovering things she never knew about herself. By Volume 4, each has had a vision of their own future, and must now choose to embrace or reject their fate, picking sides in the overarching conflict.

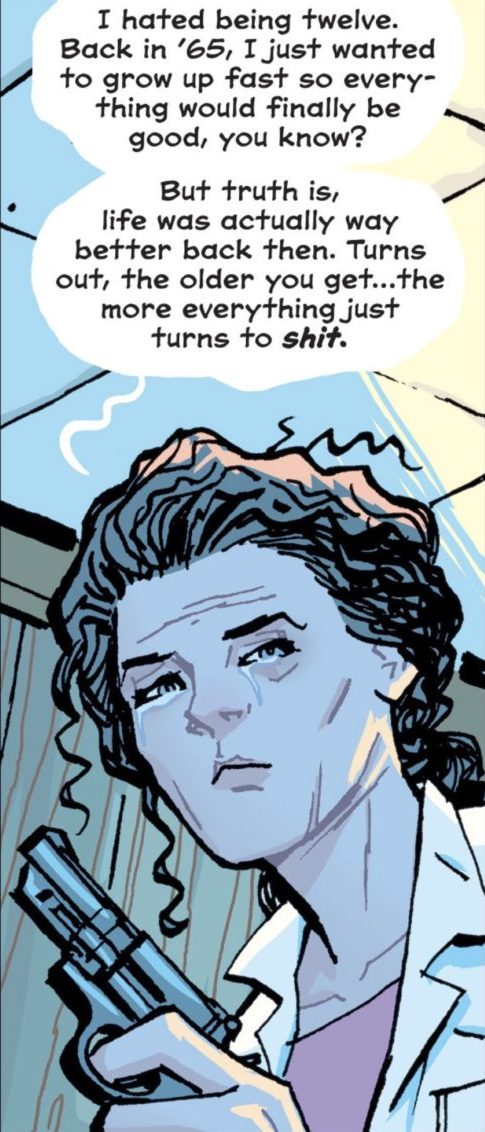

Thus the real emotional theme of Paper Girls comes to the fore: the contrast between children’s fantastic hopes for adulthood and the disappointing banality of reality. The girls discover, again and again, that adults—even, and especially, future versions of themselves—don’t control their own lives, don’t have all the answers, and are just as scared and confused as they are. They confront the realization that, except for a little less experience, twelve-year-olds are just as capable as adults when making life and death decisions. And that some twelve-year-olds never had the luxury not to face such decisions.

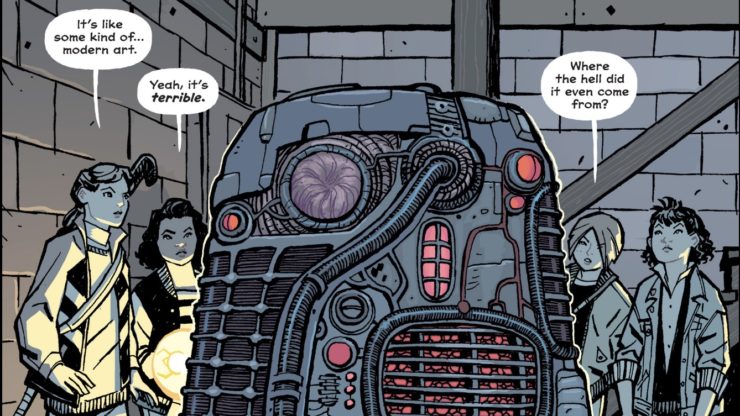

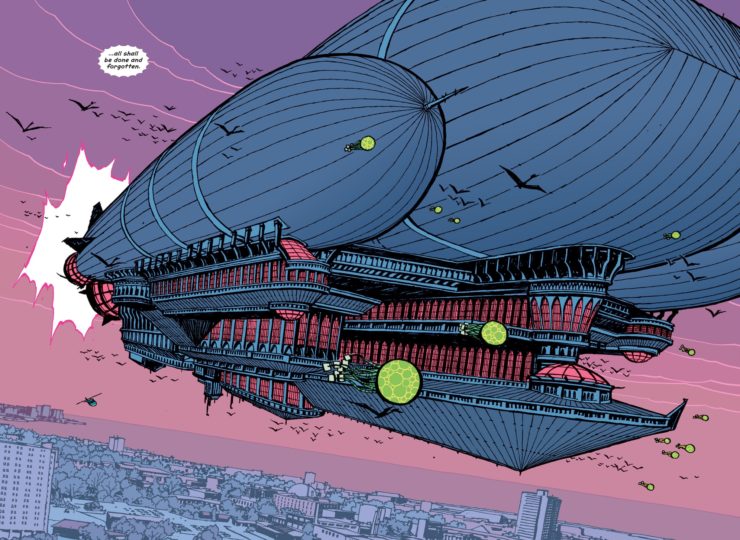

The book remains gorgeous throughout every issue, every volume. Chiang and Wilson create big moments of weirdness—invisible mecha, unraveling time machines, kaiju tardigrades, card-catalog golems—that strike exactly the right balance between recognizable and utterly inexplicable to create a sense of the uncanny in both the girls and the reader. But they really shine in the quiet emotional moments of contemplation and realization. The most powerful moment of the series so far is an impossible hug that stretches across decades, full of catharsis and healing. It’s glorious and moving, and also awkward and funny.

Buy the Book

Paper Girls, Volume 1

And Fletcher’s design creates storytelling throughout the book, literally from cover to cover. Each issue begins with a quote from or about the respective time period, and ends with an image of something important that was dropped. Fletcher even created his own alphabet for the teenage Rebels, who are from so far in the future they speak something we can’t recognize as a language.

Paper Girls is very funny, as our pop culture-savvy heroes react to the impossible with worried acceptance: they’ve seen it all before in movies and cartoons. It’s tightly focused on the kids, and all happens in the same place, a fictional suburb of Cleveland called Stony Stream, over the course of only a few days, relatively speaking. The tight focus keeps the plot moving and the feeling claustrophobic: no matter how big the problem, we stay at ground level with the children, just trying to not get squished.

That focus also obscures how tightly-plotted the time travel story line actually is. We learn things only as the girls do, and the slow drip of information can be frustratingly slow. There are major questions that are so far left unanswered. We know a lot about the Old Timers and their leader Grandfather, but almost nothing about the Rebels. We don’t know what the apple imagery means, or what it has to do with the devil imagery. We don’t know what the Calamity is. And most crucially, we don’t know if history can even be changed. The war assumes that it can (with the Old Timers insisting it shouldn’t be), but everything we’ve actually seen suggests that the universe is deterministic, and that someone who dies stays dead.

On the other hand, the reward of seeing all the strands connect makes the series a supreme pleasure to re-read. Everything happens for a reason, even if the cause happens five issues after and ten thousand years before the effect. A major reveal in the latest issue (#22), was carefully set up in issue #15. And there are major hints that the girls aren’t just bystanders in the temporal conflict, but are actually key players at every important moment in the history of time travel.

I have no idea where the series is going, or how much longer it will last. There are at least two more eras the series must visit before it wraps up: the far, far future of the teenage rebels, and 1992 (where we know that something major happened and a major character supposedly dies). Other than that, though, the series could wrap up in three more volumes, or continue on indefinitely, as the girls jump through time again and again, hoping each time that the next leap will be the leap home.

(The girls, by the way, don’t get that reference, because Quantum Leap debuted in 1989.)

Steven Padnick is a freelance writer and editor. By day. You can find more of his writing and funny pictures at padnick.tumblr.com.