Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

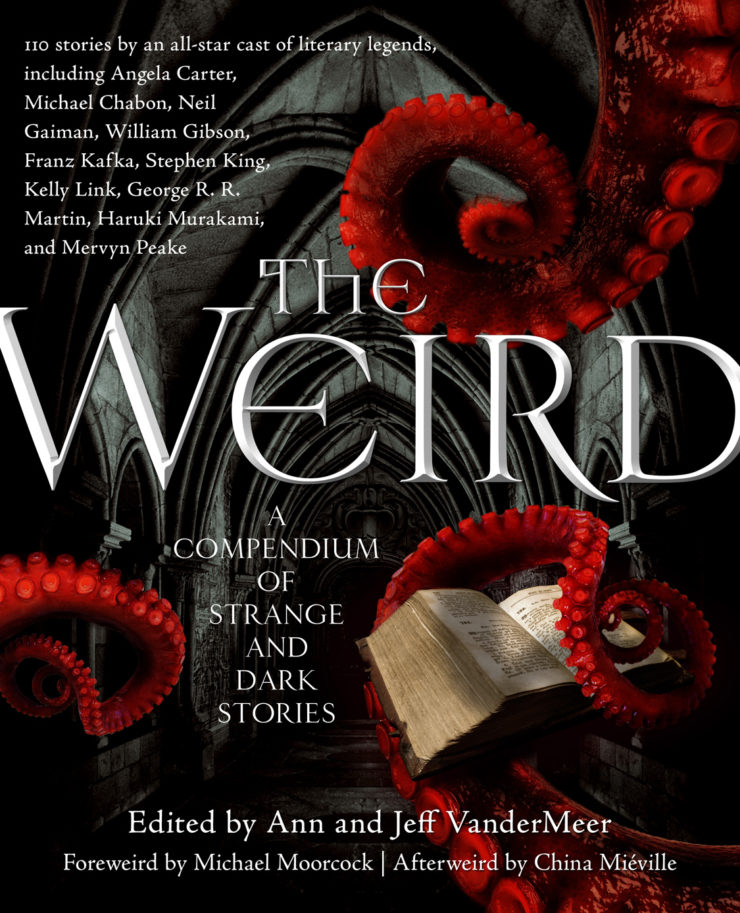

This week, we’re reading Margaret Irwin’s “The Book,” first published in 1930 in The London Mercury and collected in The Weird (Tor Books, 2012). Spoilers ahead.

“From among this neat new clothbound crowd there towered here and there a musty sepulchre of learning, brown with the colour of dust rather than leather, with no trace of gilded letters, however faded, on its crumbling back to tell what lay inside.”

Summary

One foggy November night, bored by his detective story, Mr. Corbett searches for more palatable bedtime reading. The dining room bookcase holds a motley collection: Mrs. Corbett’s railway stall novels, 19th-century literature from Mr. Corbett’s Oxford days, children’s fairy tales. Here and there looms a real tome “inhospitably fastened with rusted clasps.” Corbett fancies these “moribund survivors” of a clerical uncle’s library exhale poisonous breath oppressive as the fog. Is it further fancy to extract a Dickens, return for Walter Pater, and find Pater leaning into a space much too larger than the one he left?

Nonsense. Reading will calm his needlessly ruffled nerves, except… Tonight, under Dickens’ sentimental righteousness, he senses a “revolting pleasure in cruelty and suffering.” In Pater he sees “something evil in the austere worship of beauty for its own sake.”

Breakfast finds him better, until he notices there’s no gap in the bookcase. Younger daughter Jean says there’s never a gap on the second shelf—no matter how many books one takes off, it always fills back up!

After deciding his insights into Dickens and Pater prove he has keen critical powers, Corbett begins to enjoy dissecting revered authors down to their basest motivations. What a pity he’s only a solicitor—with his acute mind, he should have achieved greatness! Even his family’s unworthy: Mrs. Corbett a bore, Dicky an impudent blockhead, the two girls insipid. He secludes himself in books, seeking “some secret key to existence.”

One of his uncle’s theological tomes intrigues him with marginalia of diagrams and formulae. The crabbed handwriting is, alas, in Latin, which Corbett’s forgotten. But this is the key; he borrows Dickie’s Latin dictionary and attacks the manuscript with “anxious industry.”

The anonymous, untitled manuscript ends abruptly in blank pages. Corbett stumbles on a demonic rite. He ponders its details and copies the marginal symbols near it. Sickly cold overwhelms him. He seeks Mrs. Corbett, finds her with the whole family, including Mike the dog, who reacts to Corbett as to a mortal foe, bristling and snarling. Wife and children are alarmed by a red mark like a fingerprint on Corbett’s forehead, but Corbett can’t see it in the mirror.

He wakes next day rejuvenated, confident his abilities will elevate him above his associates! He keeps translating the book, apparently the record of a secret society involved in obscure and vile practices. But in the smell of corruption wafting from the yellowed pages, he recognizes the scent of secret knowledge.

One night Corbett notices fresh writing in modern ink but the same crabbed 17th-century handwriting: “Continue, thou, the never-ending studies.” Corbett tries to pray. The words emerge jumbled—backwards! The absurdity makes him laugh. Mrs. Corbett comes in, trembling. Didn’t he hear it, that inhuman devilish laugh? Corbett shoos her off.

The book has fresh-inked instructions every day after, generally about wild investments. To the envious amazement of Corbett’s City colleagues, the investments pay off. But it also commands Corbett to commit certain puerile blasphemies. If he doesn’t, his speculations falter, and he fears even worse consequences. Yet it remains his greatest pleasure to turn the book’s pages to whatever its last message may be.

One evening it’s Canem occide. Kill the dog. Fine, for Corbett resents Mike’s new aversion to him. He empties a packet of rat poison into Mike’s water dish and goes away whistling.

That night Jean’s terrified screams wake the house. Corbett finds her crawling upstairs and carries her to her room. Older daughter Nora says Jean must have had her recurring nightmare of a hand running over the dining room books. Corbett takes Jean on his knee and goes through the motions of soothing her. She shrinks away at first, then leans into his chest. An uncomfortable feeling grips Corbett, that he needs Jean’s protection as much as she needs his.

She dreamt of the hand leaving the dining room and gliding up the stair to her room, where it turned the knob. Jean woke then, to find the door open, Mike gone from the foot of her bed. She ran and found him in the downstairs hall about to drink. No, he mustn’t! Jean ran down to Mike, was grabbed by a HAND, knocked over the water dish in her struggle to escape.

Back in his room, he paces, muttering that he isn’t a bad man to have tried to kill a brute who turned against him. As for meddling Jeannie, it’d be better if she wasn’t around anymore.

Boarding school’s all he means, of course.

Or not. The book opens to a fresh injunction: Infantem occide. He clutches the book. He’s no sniveller. He’s superior to the common emotions. Jean is a spy, a danger. It would have been easier before he held her again, his favorite child, called her Jeannie, but it’s written in the book.

Corbett goes to the door. He can’t turn the handle. H bows over it, kneels. Suddenly he flings his arms out like a man falling from a great height, stumbles up and throws the book on the fire. At once he begins to choke, strangled. He falls and lies still.

The City men suppose Corbett committed suicide because he knew his speculations were about to crash, as they do simultaneous with his death. But the medical report shows that Corbett died from strangulation, with the marks of its fingers pressed into his throat.

What’s Cyclopean: Among the Corbetts’ books are musty sepulchres of learning, moribund and inhospitable amid the swaggering frivolity of children’s books and chastely bound works of nineteenth century literature.

The Degenerate Dutch: The initial hints of The Book’s influence on Mr. Corbett start with self-congratulatory judgment of authors’ mental states or simply their femininity: Treasure Island represents “an invalid’s sickly attraction to brutality, and other authors have “hidden infirmities.” Austen and Bronte are unpleasant spinsters: a “sub-acidic busybody” and a “raving, craving maenad” with frustrated passions.

Mythos Making: The Book has the Necronomicon beat all to hell (perhaps literally) for unpleasant side effects of reading. Yes, even Negarestani’s version. It may even give The King in Yellow a run for its money.

Libronomicon: The Book manages to insinuate its corruption into, among others, Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop, Walter Pater’s Marius the Epicurean, and Gulliver’s Travels.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Once The Book has its claws in Mr. Corbett, it seems to him that “sane reasoning power” should compel him to carry out any of its commands.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Buy the Book

Deep Roots

Books are dangerous. They can inspire, instruct, and shape the way we interpret the world. Their pages may transmit ancient secrets or ideas for massive change. Irwin, writing at just about the same time Lovecraft was scribbling notes about Al-Hazred’s masterwork, comes up with what should be the most forbidden of tomes: a book that not only worms its way into the minds of readers, but corrupts other books! I’d count that as a clever idea even if it came out last month instead of 88 years ago.

So even before The Book comes on screen, we get corruption as the suck fairy, revealing (or creating) horror within the most innocent books. Whether revelation or creation is left ambiguous—after all Mr. Corbett’s newfound judgment reflects claims he’s already heard from critics. (Untrustworthy creatures themselves, of course.) Perhaps there really are terrible things to be found beneath the surface of any book—all haunted, all dripping with Robert Louis Stephenson’s “morbid secretions.” And Corbett, alas, is picking up absolutely terrible coping strategies for being a fan of problematic things—worse than denial of the problems whole cloth, his smugness over being so brilliant as to notice them in the first place.

And that’s how The Book makes the leap from its fellow volumes to the human mind. It builds on every person’s propensity for arrogance, pride, and judgment. Mr. Corbett is no scholar of mysteries. He’s a solicitor, a financial adviser. What happens to him, the story makes clear, could happen to anyone. And overconfident financial speculation is, of course, a symptom of dangerous supernatural influence recognizable even today. Perhaps someone fished a few pages out of the fire and passed them around Wall Street?

Again and again, Irwin rejects the idea that there’s something especially vulnerable about Corbett, or that the reader might imagine themselves especially invulnerable. Everything that Corbett does is thoroughly human. The Book describes vile rituals that most authors would exoticize—Lovecraft would probably have ascribed them to the general cult of brown people, worldwide, who worship Those Gods Over There. Irwin tells us, instead, that “his deep interest in it should have convinced him that from his humanity at least it was not altogether alien.” No one is immune. No stage of civilization, no particular race, no particular culture. Commands from the book “might be invented by a decadent imbecile, or, it must be admitted, by the idle fancies of any ordinary man who permits his imagination to wander unbridled.”

And yet, Mr. Corbett does ultimately resist, and sacrifices himself for a sentiment that his reading hasn’t entirely managed to excise. And this, too, is not particularly special, is not limited to some subset of humanity. Everyone is vulnerable, but no one can claim they didn’t have a choice in the matter, either.

“The Book” also makes Corbett not-special in another way: though he’s the point of view throughout, the story is constantly aware of other people’s perspectives on what’s happening to him—sometimes by telling us directly, sometimes by showing reactions. It’s a study in the distinction between narrative and narrator, and in depicting a world that completely fails to support the most vile attitudes expressed by characters.

There are modern stories—plenty of them—that don’t manage this distinction, or that lack Irwin’s grasp of how people are persuaded into terrible behaviors one shift of attitude and one small corruption and one “I am not a bad man” at a time. Every step of Corbett’s descent rings true, and therefore the horror rings true. By the time he got to the occides (brr!), I was on the edge of my seat. And cheered when he threw the thing into the fire—and hoped like hell he had a good roaring blaze going.

Anne’s Commentary

Buy the Book

Fathomless

Gather round, guys, in a tight hunched-shoulders circle that excludes the unworthy prying hordes, for I have an ancient and powerful secret to reveal. Ready? Here it is:

We readers of weird fiction are freaking masochists.

That’s right. Why else would the BOOK, the TOME, the MANUSCRIPT, the GRAVEN TABLET, be practically mandatory features of the weird story—hence Ruthanna’s weekly headcount in our Libronomicon section? And why, practically invariably, would the BOOK, TOME, MS, TABLET be dangerous? The doorway into brain-warping dimensions, an open invitation to unpleasant guests, a sure trigger of madness?

Guys, we can face this together. We love to read. We love books. Even scary books. Even monstrous books. No! Especially monstrous books!

Okay, breathe. We’re okay. We don’t mean real monstrous books. Just fictional ones. Like Margaret Irwin’s, which though it lacks an exotic or tongue-twisting name like Necronomicon or Unaussprechlichen Kulten, has just as devastating an effect on the reader as those infamous grimoires. What powers her tale, bringing the terror of the TOME closer to home, is the reader-protagonist she chooses. Mr. Corbett, solicitor, husband, father, dog owner, is as Everyman a middle-class guy of the circa-1930 London suburbs as one could wish. He’s definitely no Lovecraftian protagonist, a solitary aesthete haunting out-of-the-way bookshops or an academic for whom books might be ranked a professional hazard. Too bad for Corbett he had a Lovecraftian protagonist of an uncle, whose estate insinuated a poisonous book in his otherwise harmless home library. Poisonous, because possessed by the will of its 17th-century author, rather like Ginny Weasley’s notebook is possessed by a bit of Tom Riddle’s splintered soul. Also like Ginny’s notebook, Corbett’s writes to him in real time.

This is not good. As Mr. Weasley warns: “Never trust anything that can think for itself if you can’t see where it keeps its brain.”

Or if you can’t see the spectral hand it uses to rearrange your bookcase and poison anything shelved near it. The manuscript’s poison is exquisitely insidious, too. It discolors the contents of infected books with its own profound cynicism—humanity is corrupt and brutish to the core, don’t you see it now, under the civilized veneer of Dickens’ sentimentality or Austen’s sprightliness? Even the people in the children’s picture books warp evil under its taint. They make Jean cry, for she’s a sensitive. She sees the spectral hand at work in her dreams.

Corbett’s initially put off by the way the book warps his sensibility. But the joys of cynicism grow on him, for one cannot look down on someone else without ascending first to a superior height. He’s an ordinary guy who’s been pretty much content being ordinary, who’s pretty much benignly envious of successful peers. The book seizes on that weak spot of “pretty much.” It convinces Corbett he’s extraordinary, underappreciated, but that will change. The Master of the book will lead him to his rightful eminence, if Corbett will shed the foolish inhibitions of those other human sheep, including his wife and children. Ought one standing on the threshold of ancient and powerful secrets spare even his favorite child?

What could the book and its ghost-author, offer Corbett that would be worth sacrificing his Jeannie? Oh, secrets, ideas, knowledge, insights, which are after all what books contain, because they contain the words, words, words that Hamlet bemoans, our bedeviling thoughts given aural and visual form. Units of exchange. Communication. Gifts. Or viruses.

Thought, knowledge, idea. Words, put down in wax or stone or ink on paper. On indestructible pages in metal files, to be shelved in the eternal libraries of the Yith. Books are precious or perilous because they pass on ideas. Knowledge. Thought. Which then recombine with the reader’s own ideas, knowledge, thought, to become more precious or perilous.

In Mr. Corbett’s case, the recombination’s so perilous his only out is to burn the book in a last paroxysm of former identity, core self.

A tragic win for the Light, but still, I hate it when the big bad book eats fire at story’s end. Which probably means I shouldn’t lead the Perilous Books SWAT Team, guys. While we’ve got our heads in this circle, let’s pick someone else.

If, in this crowd, we can find anyone. [RE: Okay, I admit it was pretty uncharacteristic for me to cheer a book burning. Maybe The Book is corrupting me too. The horror! And the intrigue of the paradox.]

Joanna Russ’s praise of this story reminded us how much we like her stuff too, so next week we return to The Weird for “The Dirty Little Girl.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Have y’all ever considered reviewing “The Night Wire” by H.F. Arnold?

I didn’t remember the author, but I’m sure I’ve read this at some time, in some anthology. I clearly remember the “canem occide” and “infantem occide” progression and the ending.

I had never heard of Walter Pater, but he was apparently fairly popular in the late 19th century and was something of an inspiration for the Aesthetic movement. I wonder if there’s some sort of symbolism in the author choosing his work or if it’s meant to tell us something about Corbett, maybe just another tag of his prosaic, middle-class existence. (One of the sources on the Wiki page for Pater is AC Benson, brother and fellow ghost story writer of EF Benson, who has appeared here a few times.)

I just wonder what would have happened if the book told him to kill his least favorite child first…

There’s something I don’t quite understand about the gap between the books being larger than it should be after he removed the Dickens. If the bookshelf always fills in missing spaces, shouldn’t it be smaller? And what does it fill in the spaces with?

Perhaps the reason the space seemed too wide was that he had not, in fact, taken the Dickens. He had taken The Book, which had not so much corrupted as absorbed the other books around it – every book on that shelf in time becomes The Book, although it outwardly still looks like it should. And any gaps are filled in with More Book.

“a book that not only worms its way into the minds of readers, but corrupts other books! I’d count that as a clever idea even if it came out last month instead of 88 years ago.”

For some reason there are several similar ideas on SCP Foundation – a minor character (quite harmless actually) that keeps inserting himself in different books, and so on.

For some reason, this reminded me of Pontypool, although in that case it’s not written language, but spoken English, that becomes a virus (in a very literal sense, because it’s a zombie movie). Maybe it’s the infectious aspect, I’m not sure.

I’ll have to seek this one out!

For some reason, the comparison of this book and its chosen cultist with Lovecraft’s brand of cult and gods reminded me of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Good Lady Ducayne. Braddon was a friend of Bram Stoker, and wrote Ducayne at about the same time Stoker wrote Dracula – but while Dracula is a figure from a distant land wielding superstitions of the distant past, Lady Ducayne was from English society and using modern technology for her vampirism – the same blood transfusions Van Helsing uses to save Lucy. I’m not really sure what point I’m fumbling around at, though it jumped out at me that in both pairings it’s the female writer who puts the evil into conventional society.