In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

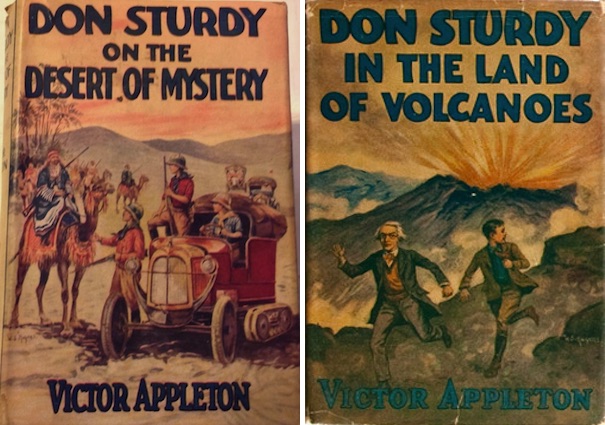

The years spanning the late 19th and early 20th Centuries were a time of adventure. The last few blank spots on the map were being filled in by explorers, while the social science of archaeology was gaining attention, and struggling for respectability. And young readers who dreamed of adventure could read about a boy explorer in the tales of Don Sturdy, a series from the same Stratemeyer Syndicate that gave the world stories about Tom Swift, Nancy Drew, and the Hardy Boys. They were among the first—but far from the last—books I read that are fueled by tales of archaeological discovery and the mysterious lure of lost lands and ruined cities.

When you re-read books from your youth, you are often surprised by what you’ve remembered, and what you haven’t. Sometimes the surprise is pleasant, sometimes it is not. When I reviewed On a Torn-Away World by Roy Rockwood, another Stratemeyer Syndicate tale, I found that the book didn’t live up to what I remembered. I am pleased to report that I had the opposite experience with these two Don Sturdy books, which I’d discovered on the bookshelf of my den. They held up well on re-reading—far better than I thought they would.

Some of you may question whether these books are even science fiction, and you may be right: The scientific content is thin, and mostly exists to put the protagonists in exciting situations. But the stories are packed with action and adventure, and there are plenty of mysteries to be uncovered in strange and exotic locations filled with the wonders (and dangers) of nature.

Moreover, re-reading these books confirmed something I had thought for a long time. When I first encountered George Lucas’ Indiana Jones in the cinema, I immediately thought of Don Sturdy and his uncles, traveling the world searching for zoological specimens and ancient treasures. Lucas has always been coy about the influences that led him to create Indiana Jones, but there are many clues in the Young Indiana Jones television series. And in one episode (“Princeton, February 1916”), Indy dates one of Stratemeyer’s daughters, which indicates that Lucas was familiar with the works of the Stratemeyer Syndicate. If Don Sturdy was not a direct influence for the character of Indiana Jones, he certainly grew out of the same tradition that led to Indy’s creation.

About the Author

Like all books published by the Stratemeyer Syndicate, the Don Sturdy books were written under a “house name,” in this case “Victor Appleton,” the same name used on the Tom Swift books. The stories were actually written by a man named John William Duffield. Very little information is available about Mr. Duffield, so this summary relies heavily on his entry at the always useful Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (SFE) website. We know that he lived from 1859 to 1946, and that he did significant amounts of work for Stratemeyer, writing under a variety of house names. He wrote books in the Ted Scott Flying Series and the Slim Tyler Air Stories. He wrote the earliest books in the Radio Boys series, which included factual articles about the devices and techniques used in the stories themselves. He wrote many of the books in the Bomba the Jungle Boy series, which I remember enjoying as a boy, and which led to a series of movies.

From the two books I read for this review, I can make a few other observations: Duffield was a better writer than many of his Stratemeyer Syndicate counterparts, constructing his stories with cleaner and more straightforward prose. While his books relied on some of the clichés and conventions of adventure books of the time, it is apparent that he did his research. The chapter endings encourage you to read further, but not in as blatant a way as some of the cliffhangers in other Stratemeyer books. If he did not visit the Algerian and Alaskan settings of the two books, he clearly read about them, as many of the towns and locales described in the books actually exist. And the books, while they sometimes reflect the casual racism of the time, are not as flagrantly offensive as some of their counterparts.

Archaeologists and Explorers

As I mentioned earlier, the last decades of the 19th Century and early decades of the 20th Century were the culmination of centuries of exploration, a topic that always fascinated me as a youngster. Those decades also saw an increasingly scientific approach to these efforts. In my recent review of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, I looked at the emerging science of paleontology. Trophy hunting was giving way to the science of zoology, and treasure hunting was giving way to a more scientific approach to archaeology. I remember visiting the American Museum of Natural History in New York in my youth, and learning about Roy Chapman Andrews traveling the world to collect zoological samples and fossils for the museum, and about Howard Carter opening the tomb of King Tut. Every schoolkid of the era knew the story of Sir Henry Stanley traveling through Central Africa and uttering the immortal words, “Doctor Livingstone, I presume?” We were all fascinated by tales of polar explorers, including Admiral Peary and Matthew Henson’s many Arctic expeditions, and I remember building a plastic model of the Ford Tri-Motor airplane used by Admiral Byrd’s 1929 Antarctic Expedition. Other adventures that caught my imagination were Heinrich Schliemann’s uncovering the ruins of the fabled city of Troy, and Teddy Roosevelt’s travels through Africa, South America, and the American West. I also remember my father’s personal recollections of watching Charles Lindbergh take off across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis. So, of course, tales like the Don Sturdy adventures were immediately appealing to me.

Science fiction has often borrowed from archaeological adventures. This includes explorers encountering Big Dumb Objects, like Larry Niven’s Ringworld and Arthur C. Clarke’s Rama. Andre Norton gave us many tales involving abandoned ancient ruins and caves full of mysterious artifacts. One of my favorite science fiction stories, H. Beam Piper’s “Omnilingual,” follows archaeologists in an ancient city of Mars as they search for a “Rosetta Stone” that will allow them to read the records of the lost civilization. Even the climax of the movie Planet of the Apes takes place at an archaeological dig where ape scientists have been attempting to discover secrets of past civilizations. And there are many other tales as well, too numerous to recount (you can find a recent Tor.com discussion of SF set in dead civilizations here). There is something awesome and compelling about these efforts to tease out the secrets of the past.

Don Sturdy on the Desert of Mystery

The book opens with its main characters already in Algeria—a refreshing change from stories in which whole chapters elapse before the adventurers finally leave home. We meet Captain Frank Sturdy, Don’s uncle on his father’s side, and Professor Amos Bruce, Don’s uncle on his mother’s side. They are discussing an expedition to cross the Sahara in automobiles in order to reach the Hoggar Plateau, where they might find the legendary Cemetery of Elephants. Captain Sturdy is a man of action, a skilled hunter, and a collector of zoological specimens from around the world. Professor Bruce is a skilled archaeologist, and extremely learned. Don Sturdy himself is only fifteen years old, but already an accomplished outdoorsman and a crack shot. Don believes himself to be an orphan, as his father, mother and sister were aboard the Mercury, a ship that recently disappeared rounding Cape Horn. Thus, Don has found himself under the guardianship of two men who roam the world seeking adventure—something any boy would envy.

Don is out hunting when he witnesses two men attacking a boy. When he realizes the boy is white like him, he immediately intervenes, and with his excellent marksmanship, drives the attackers away (I am disappointed that race entered into his decision-making in this scene, even if it does reflect the attitudes of the time in which the tale was written). The rescued boy, Teddy, is from New York, and has a sad tale. His father was an explorer in search of the legendary Cave of Emeralds, and was attacked and captured by bandits. One of the Arab members of the expedition had rescued Teddy and taken him in. When Teddy tells his story to Don’s uncles, they immediately decide that their expedition has an additional goal: to rescue Teddy’s father.

Captain Sturdy is planning to purchase not just any vehicles for their expedition across the desert, but half-tracks, newly invented during the Great War, which will allow them to travel through terrain previously thought impassable. By happy coincidence (there are a lot of coincidences in these books), Professor Bruce finds a dependable local guide, Alam Bokaru—only to find he is the very man who had rescued Teddy. He is hesitant to join their expedition, however, because the fabled City of Brass is near their destination, and to observe that city from the back of a camel brings death, according to legend. When the men point out that they will not be riding camels, he reluctantly agrees to assist them. But the men who had attacked Teddy have been lurking, and will hound the explorers throughout their journey.

I won’t go into too much detail about their expedition, but the explorers deal with mechanical problems, encounter tarantulas, get buried by a sandstorm, clash with bandits and brigands, and along the way find clues that point them toward the destinations they seek, along with the fate of Teddy’s father. Many shots are fired, but due to their outstanding marksmanship, the Sturdys are able to prevail without killing anyone (something that, while somewhat unbelievable, keeps a book intended for children from having too high a body count). The adventures are sometimes sensational, but are presented with enough realistic detail to allow you to suspend your disbelief. And a chance encounter late in the book (another of those numerous happy coincidences) brings news that survivors from the Mercury had been found, and so our intrepid adventurers end the book making plans to voyage to Brazil in the hopes of reuniting Don with his family.

Don Sturdy in the Land of Volcanoes

The book opens with Don in his hometown, having been reunited with his family over the course of previous volumes. He helps a young girl who is being forced into a car by a local bully, only to have the car speed through a nearby puddle, covering them both with mud. Then, in the second chapter, we encounter the dreaded expository lump that is a hallmark of Stratemeyer novels, where the author recounts the previous adventures of our hero, complete with all the titles of earlier books in the series. (It occurs to me that this lump may have been added by other hands and not Duffield himself, as the prose feels stiffer than that in the rest of the book). It turns out that this is fifth book of the series, and that the reason we were spared the expository lump in Desert of Mystery is because it was the initial book in the series. We meet the Sturdy’s servant Jenny, whose dialogue is presented in a thick vernacular, and whose purpose is simply to misunderstand things for comic relief (unlike in many other Stratemeyer books, however, she is refreshingly not identified as a person of color). We also learn that the bully’s father has been manipulating property titles in an attempt to force the Sturdy family from their home.

Fortunately, Uncle Frank arrives with a proposition for Don that will rescue him from these domestic concerns. He and Uncle Amos have been commissioned to travel to Alaska, and want Don to help them gather specimens and geological samples from the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes (the fact that the Professor is an archaeologist is overlooked for the sake of the plot in this volume). This valley was created after the eruption of Mount Katmai in 1912, and still exists today in the Katmai National Park and Preserve. Even better, they suggest that Don bring along his old friend Teddy.

They travel across the country by train and step aboard the Margaret, the yacht which they will be sharing with another party of scientists. The boys are interested in the engine room, and while the Scottish engineer gives them a tour, the author takes the opportunity to provide some educational information about steam engines to his young readers. They then encounter a fierce storm, receive a distress call from a sinking vessel, and Don gets a chance to be a hero due to quick thinking (I will point out, however, that large waves break only when water shallows, and so breakers are not generally encountered in mid-ocean). Later, the boys help solve the mystery of a rash of thefts on the yacht, earning the hatred of a seaman who will be a recurring antagonist during the remainder of the tale.

The geological wonders they encounter are very evocatively described, and over the course of their travels they encounter fierce Kodiak bears, Don is almost swallowed up by a deposit of volcanic ash, they survive close shaves with volcanic eruptions, and of course, ruffians are driven off by the obligatory display of crack marksmanship. They also encounter a fierce storm they refer to as a “woolie,” which springs up out of nowhere with hurricane force winds. From my own Coast Guard experience in Alaska, when we called them “williwaws,” I can attest to the fierceness of these sudden storms. The one flaw that irked me in these adventures is that the boys’ packs are described as weighing forty pounds, but seem to have the TARDIS-like quality of being “bigger on the inside,” as their four-man party never lacks for equipment or supplies, and are able to carry out large quantities of animal skins and geological samples.

On their way home, through yet another one of those happy coincidences so common in Stratemeyer books, they discover some crucial information about the man attempting to foreclose on the Sturdy home, and the book ends well for all concerned.

Like the first book of the series, this one was an enjoyable read. The writing is solid, and displays a lot of research, if not personal experience, on the part of the author. There are the usual clichés of the genre, but the book has an overall sense of realism that is so often lacking in other books of the time.

Final Thoughts

In the 1920s, boy’s adventure books were cranked out by the literary equivalent of assembly lines, and quality control over the product was often lacking. The Don Sturdy books, however, stand out because of the quality of the prose and the evidence of careful research and attention to detail. They have their flaws, but have aged far better than some of their contemporaries.

And now I turn the floor over to you: If you’ve read any Don Sturdy adventures, or other tales from the Stratemeyer Syndicate, what did you think? And are there other fictional stories of archaeology and exploration that struck your fancy?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.