Many fans of J.R.R. Tolkien already know that there is, right now, a free and rare exhibit of the professor’s many works at Oxford University’s Bodleian Libraries running through the rest of October. It’s a dragon’s hoard of hand-drawn maps, illustrations, and book drafts—many of which have never been presented publicly before—all on display, along with an assortment of wonderfully nerdy and decidedly hobbitish accoutrements like Tolkien’s writing desk, pencils, chair, and smoking pipes. And some of us are also giddily excited about that same exhibit coming to the Morgan Library & Museum in New York next year. It’s a veritable Elf-studded, high fantasy equivalent of the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage in the Bronx or the Mark Twain House in Connecticut.

The exhibit is called Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth and from what I’m hearing, it’s any Middle-earth geek’s delight. But it’s also finite. By mid-May next year, all those original works will be closed up one last time like the Doors of Durin, Watcher-style, then whisked back into the vaults of private collectors, the Tolkien Estate, Marquette University, and the Bodleian itself. But for those fans who can’t make it to these far-distant museums and still want to experience some of that awesomeness…well, there’s a book for that!

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth, like the exhibit, is about the man himself. Which means this is really more about appreciating the depth of the human being behind the stories we love. Now, to own this hefty coffee table book, you’d probably want to be someone who loves the books already—maybe the films, too, but those’re way less important—because the material in here is like an Extended Edition of the professor’s own tale.

What it is: A compelling and extraordinarily rich account of J.R.R. Tolkien’s life and literary history interspersed between three hundred images, all of which are scans from manuscripts, photographs, original sketches—even doodles!—and watercolor paintings of his own creation. Not to mention some fun letters written by him, to him, or about him…such as the handwritten Christmas gift card written by “Wanild Toekins” (i.e. phonetically transcribed by his mother, Mabel) and allegedly delivered by Santa Claus to his father, “Daddy Toekins.” This was back when little 2-year-old Ronald would frequently ask for “penkils & paper” to write with.

Buy the Book

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth

To start things off, there are six essays written by well-known Tolkien scholars:

J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch — Written by Bodleian Library archivist Catherine McIlwaine (who also put this whole book together), this account gives us Tolkien’s life in a halfling-sized nutshell: his youth, his many losses, his wife, World War I, his kids, and the creative and linguistic genius that ran through it all.

Tolkien and the Inklings — Written by Tolkien scholar John Garth (Tolkien and the Great War, et al.), this one zeroes in on the camaraderie of the famous literary discussion group and social circle of which Tolkien was a key member. Though these academics famously met at the Eagle & Child pub in Oxford, the Inklings began long before in private rooms and informal spaces—and more officially launched when Tolkien founded a book club specifically intended “to show Oxford faculty staff that reading the medieval Icelandic sagas in the original Old Norse language could be fun.” (Yeah, that showed ’em!) His friendship with C.S. Lewis, of course, features prominently in this essay, as does the banter, the good-natured ribbing, and even the brutal criticism that defined the social circle.

Faërie: Tolkien’s Perilous Land — Written by author and mythology specialist Verlyn Flieger (Splintered Light, et al.), this one dives right into Tolkien’s obsession with that elusive world beyond worlds: Faërie, a concept that can be as hard to define as it is easy to be caught up in. She explains how sections of Tolkien’s best-known works, such as those set in the Mirkwood and Old Forest, may be his most recognizable treatment of Faërie, but its otherworldly and mysterious qualities can be found throughout his legendarium. The esteemed Flieger—who, by the way, was recently interviewed on The Prancing Pony Podcast (totally worth listening to)—has a deep and longstanding investment in Tolkien’s world: she read The Fellowship of the Ring in 1956, before it was the worldwide phenomenon it is now.

Inventing Elvish — Written by NASA computer scientist Carl F. Hostetter (Tolkien’s Legendarium, et al.), this essay showcases the author’s own passion for languages by exploring the real heart of Tolkien’s worlds: Elvish, his “secret vice,” the thing that shows the professor really was a word nerd first and a fantasy author second. While casual readers of The Lord of the Rings know modes of Elvish only in some scattered dialog, on the Doors of Durin, or inside the One Ring to Rule Them All, it provided the framework upon which Middle-earth coalesced.

Tolkien and ‘that noble northern spirit’ — Written by Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey (The Road to Middle-earth, et al.), this essay sheds light on the man’s chief literary inspiration: tales of the Old North and Norse mythology. Not only does he touch on some of the legendarium’s more poignant moments that invoke “the Old World of the barbarian past” (such as the horns of Rohan blowing at dawn during the siege of Gondor), Shippey also gives us a crash course on the origins of the modern world’s discovery of Norse mythology in the first place. Like, how the story we know as Beowulf was just an obscure poem some nineteenth-century Finnish doctor found lying around and decided to publish. Then there was that time when a Danish scholar in the seventeenth century released a thirteenth-century work of literature, The Prose Edda. And this, in turn, helped to introduce a whole bunch of Norse elements to the world at large:

The mythological tales of The Prose Edda, in particular, very soon ‘went viral’: everyone now knows about Ragnarök and Valhalla, Thor and Odin and Loki.

Tolkien’s Visual Art — Written by Tolkien scholarly power couple Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull (The Lord of the Rings: A Reader’s Companion, et al.), this essay zooms in on the professor’s own efforts as an amateur, yet most impressive, illustrator. Since Tolkien’s drawings and watercolor paintings complement his stories, and have informed many artists ever since, this subject is central to the purpose of the book.

Speaking of which, let’s talk about some of the specific images at hand. Sure, there are some excellent photographs of John Ronald Reuel at all stages of his life—such as the family portrait on page 115 taken in South Africa when Tolkien was only ten months old that, “[u]nusually, in a country marked by racial divisions…also included the household servants.” Or the photo of 3-year-old Ronald with his little brother, Hilary, both dressed in Victorian outfits “feminine to the modern eye” on page 121. But honestly, there’s no point in merely listing them. There are too many.

Really, you should just go and get this book if you can bear the cost. Of the hundreds of illustrations, here at least are three in particular that stand out to me.

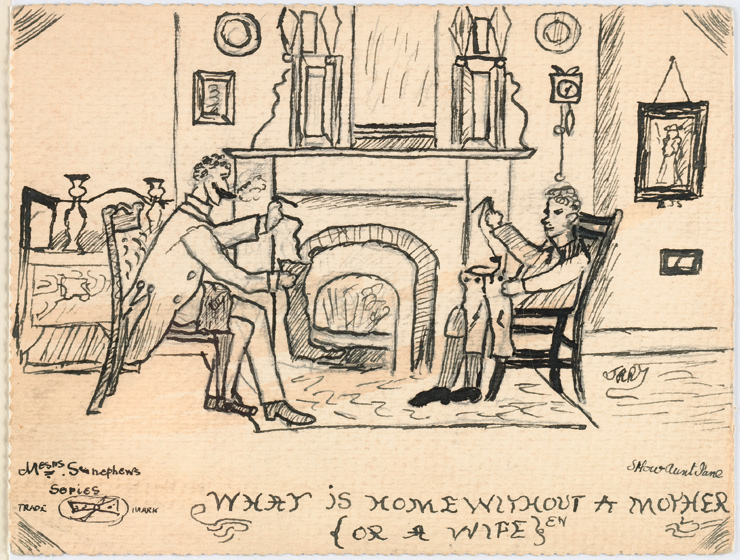

Consider this drawing he made at the age of 12, when Ronald and his brother were temporarily separated after their mother, Mabel, took ill (diabetes, being nearly untreatable in 1904). While she was hospitalized, he was sent to stay with an uncle in Brighton. As many kids do, he sketched the things around him that reflected his circumstances; then he had these drawings sent to his mom like little postcards. This one shows young Tolkien mending clothes with his uncle in front of a fireplace (a hobbitish image in itself, isn’t it?), getting by and doing normal things out of necessity in the absence of his mom. It’s charming and it’s simple (though what a moustache!), but it’s the title Tolkien gives it that sticks with me: What Is a Home Without A Mother {Or a Wife}

Readers of The Lord of the Rings see very little of motherhood in Tolkien’s work. Sure, we know there are some moms—Belladonna Took, Gilraen, even Galadriel—but we never really see anyone being a mother. Aragorn’s mother may be the only exception, but while her story is very touching, it’s tucked away in the Appendices. Readers of The Silmarillion know there are quite a few more moms to be found therein, but they’re usually wrapped in tragedy or misfortune, such as with the Elf Míriel, mother of Fëanor, who chooses to die after she’s given birth to her legendary son; the Maia Melian, mother of the incomparable Elfmaiden Lúthien, who loses her daughter to mortality itself; and Morwen, mother of Túrin, the ill-fated hero of Men, who sends her son away when he is eight years old and, despite both their efforts, never sees him again.

Sadly, Tolkien lost his mother the same year he made this drawing—a drawing that shows he thought the world of her, and missed her, and was trying to put on a brave face in her absence by doing normal things. For someone with such an imagination, who spent so much of his life illustrating fantastical things, young Tolkien’s scene of utter realism is poignant.

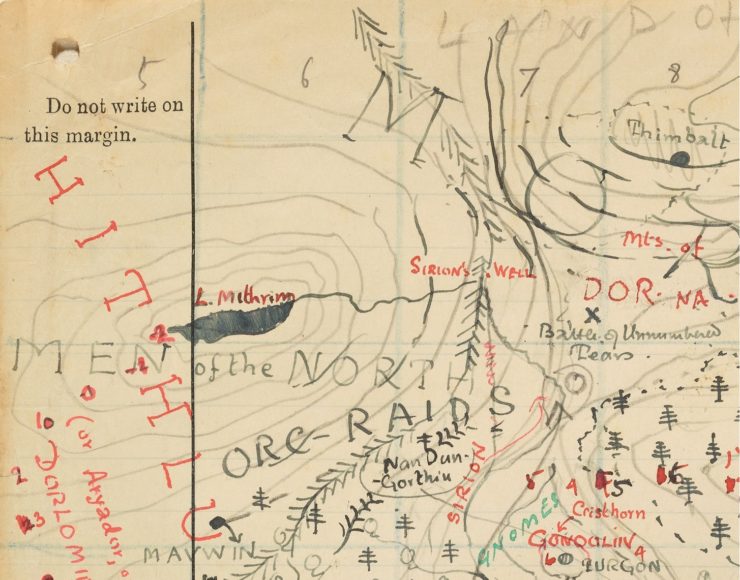

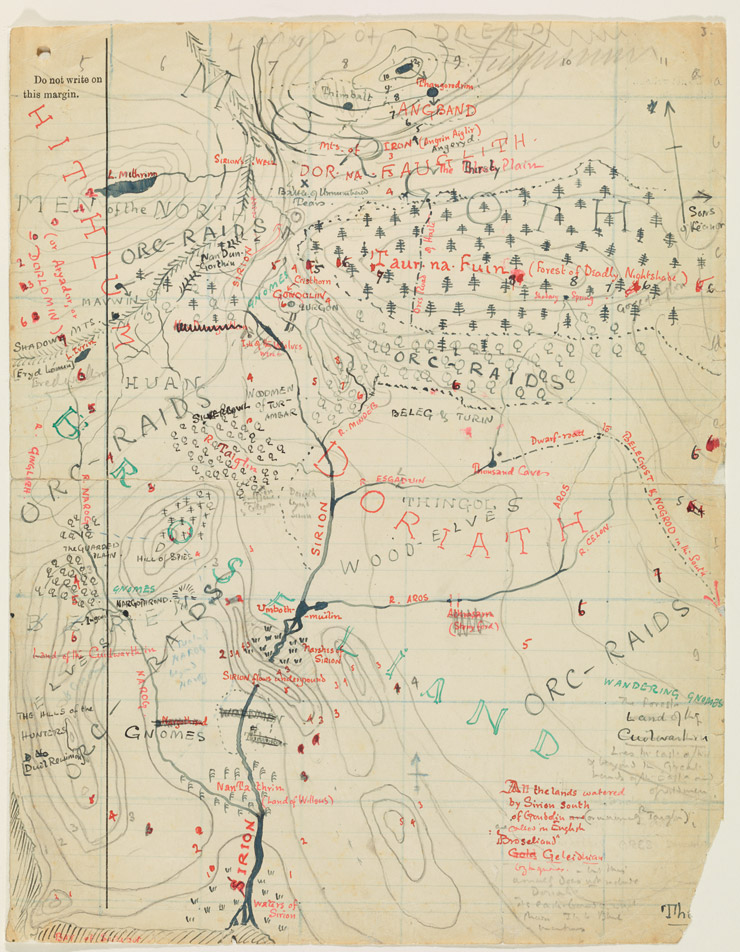

Let’s move forward in time. Of all the maps in this book, the one that I was most excited to see up close is the first Silmarillion map ever! First revealed in 1986’s The Shaping of Middle-earth, only in the hardcover edition has it been seen like this before. Here it’s nice and clear and in color, being the first map of Beleriand (which Tolkien had been calling “Broseliand,” at that point in time), the north-western corner of Middle-earth where all the events of The Silmarillion play out before its destruction at the end of the First Age. Tolkien worked up this map in the late 1920s or early 1930s.

It’s a wonderful color-coded mixture of the topographic and the narrative. And it’s clear he’d been working out so many stories in his head during this time, though we wouldn’t know about them until at least 1977. Like, who the heck were the sons of Fëanor to anyone else in mid 1920s?! (See the arrow pointing to the east.) And look how integral to both geography and story the river named Sirion is. Good old Sirion.

That said, my favorite features of this map are:

- Angband, the mountain-fortress of Morgoth, is actually shown and labeled here. None of the usual published maps of Beleriand gave us this, leaving us to deduce its location.

- A “Dwarf-road” is drawn leading from somewhere off the page (east) all the way right up to the “Thousand Caves” (of Menegroth) in the Elven woodland of Doriath. In The Silmarillion, this road is much shorter and terminates well before reaching the forest. This is indicative of a very different iteration of First Age events, where the Dwarves seem to have greater access to the Elven lands. More in keeping with events in The Book of Lost Tales.

- Gnomes everywhere! Written multiple times. “Gnomes” being Tolkien’s early word for the Elves later known as the Noldor.

- Huan, the best dog in the whole universe from any mythology, is labelled here, indicating his territory. In the early days of this version of Middle-earth, he was an independent and free-roaming agent, keeping the land safe from the early predecessor of Sauron, that dastardly Prince of Cats, Tevildo.

It’s no coincidence that the regions covered in this map are heavily trafficked by the three central tales Tolkien had been working on that would snowball, in time, into The Silmarillion itself. That is, the “Great Tales” of The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, and The Fall of Gondolin.

But my uttermost favorite part is in the upper left corner: Do not write on this margin. Those aren’t Tolkien’s words, of course, but they’re proof that he drew this momentous, highly formative fantasy map using, effectively, office supplies. Specifically, on “an unused page from an examination booklet from the University of Leeds.” Even the world’s most famous fantasy author was daydreaming at his day job. It’s nice to be able to relate.

And also, who hasn’t written ORC-RAIDS on their school papers before?! Am I right?

In the same vein, it would have been around 1930 that he wrote his famous “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit” on the blank page of an exam-book while grading papers.

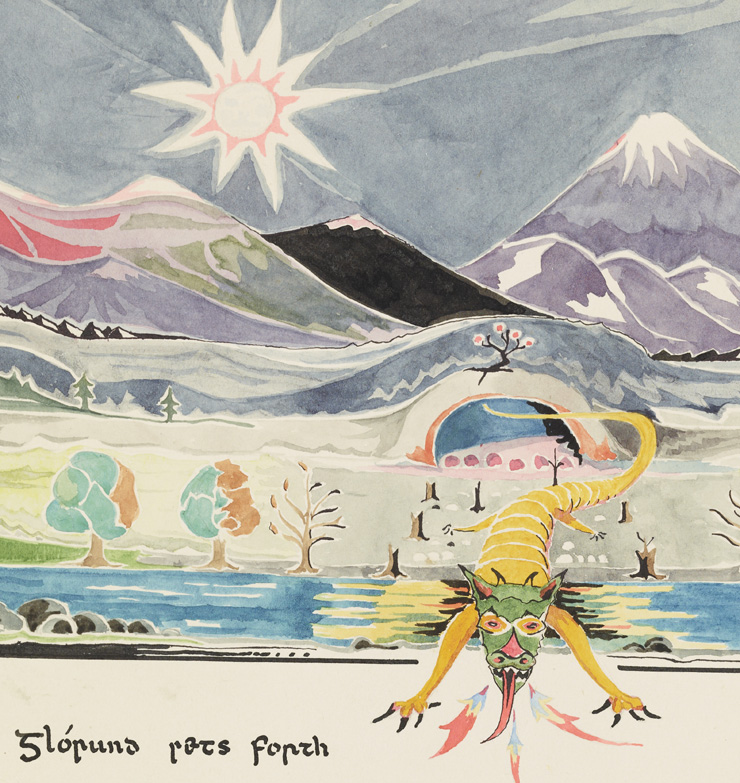

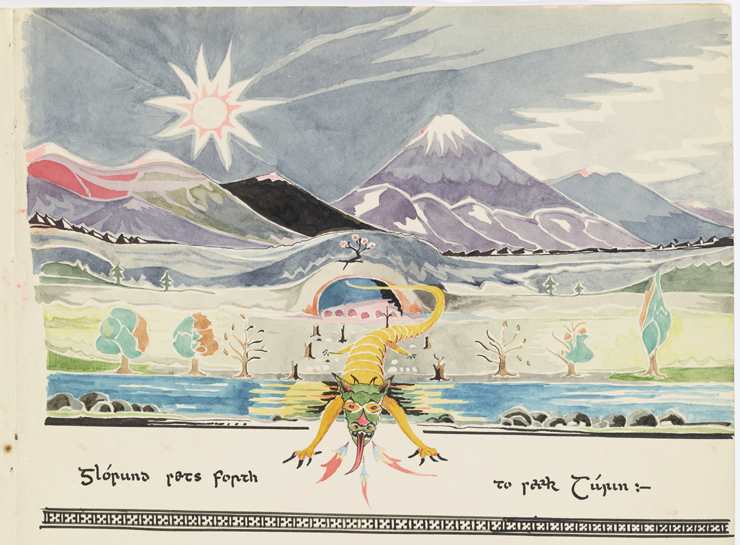

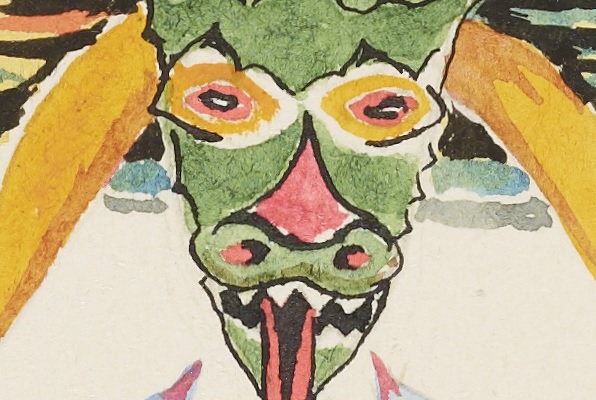

Now, we need to talk about Glaurung, the first dragon created by the Dark Lord, Morgoth—or, rather, Glórund, as he was first called in The Book of Lost Tales. He is the bane of the Elves’ existence in the First Age, at least until the mortal hero Túrin Turambar puts an end to him—but not before Glaurung made the guy’s life a living nightmare (in truth, many other things contributed to the Man’s misery—such as Túrin Turambar himself).

In 1927, Tolkien made the following illustration. Note that this is ten years before the publication of The Hobbit. That’s right: before he’d even thought up Smaug the Tremendous, Chiefest and Greatest of Calamities, there was this Glórund fellow…

Tolkien’s black ink and watercolor illustration of Glórund is remarkable—nay, fabulous!—and not the least because he made this dreadful beast mustard yellow. Well, to be fair, he was called “the golden,” and the father of dragons, and his eyes could enthrall anyone who looked in them. Both Túrin and his sister, Nienor, are thus enspelled by his gaze when they first meet Glaurung and are sent hurtling down a ruinous path in their lives.

As a hot and heavy dragon, he of course bears little resemblance to the winged Smaug we’re all more familiar with. Glórund was the first of the First Age dragons, but also the greatest in those days:

but the mightier are hot and very heavy and slow-going, and some belch flame, and fire flickereth beneath their scales, and the lust and greed and cunning evil of these is the greatest of all creatures

In this scene, Glórund is emerging from his lair in the ruins of the Elf-city of Nargothrond, which he himself had thoroughly ransacked with an army of Orcs. Glórund has been called on by his master, Melko (the early name for Melkor/Morgoth) to seek Túrin again after the mortal resurfaced some years after their first meeting. And so he crawls out of the tunnel and across the river, slow and ponderous, yet terrible.

So what are we to make of the size of Glórund based on the cave he’s coming out of? What about those crazy water-goggle eyes of his? And why don’t any of the Tolkien artists model their Glaurung illustrations after this one? Why do we seldom see any yellow-bodied, green-headed Middle-earth dragons who look like they were hopped up goofballs anywhere else? John Garth, the scholar I mentioned above, explains on his blog why we shouldn’t look for for too much realism in these originals:

Tolkien’s pictures cannot be taken as empirical evidence. They are heavily stylized, as befits a story with medieval or legendary/fairy-tale overtones. So, frequently, are his Middle-earth writings.

Tolkien admitted that his Bilbo in ‘Conversation with Smaug’ is not depicted to scale. ‘The hobbit in the picture of the gold-hoard, Chapter XII, is of course (apart from being fat in the wrong places) enormously too large. . . . It’s clear that the picture ‘Glorund sets forth to seek Túrin’ is even less likely to represent actual proportions: it is explicitly medieval in style, where ‘Conversation with Smaug’ has more in common with the classic children’s book illustration of the late 19th and early 20th century – Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, and so on.

To me, it’s the scenery in this piece that’s arguably the best part of it. Though he was humbly self-deprecating about his own illustrations, Tolkien (I think most of us would agree) invokes the realm of Faerie in his art. You can’t look at his skies and landscapes, forests and rivers, houses and towers and not feel like you’re looking into another world.

But still … those eyes! Maybe Glórund’s just got us all in thrall…

So, there you have it. This has really just been a brief glimpse into one awesome and lore-packed book. Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth is the book beyond the exhibit, which endures even as the other diminishes and sails into the West. It’s sure to enrich any fan’s appreciation for Tolkien the mortal Man, who despite having left this world has at least left behind another of his own creation. A vast, believable, alien-yet-familiar, and somehow still scarcely inhabited world: Middle-earth, which seems to be half the Earth we know and half an Earth we don’t. One that’s steeped in Faerie.

Ultimately, J.R.R. Tolkien was just a guy who loved to study and create languages, adored medieval poetry, loved his wife, wrote stories for his children, and turned out to be rather brilliant at all of it—to our great benefit. He was just a dreamer who totally wrote on that margin, and I’m really glad he did.

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth is available from the Bodleian Library.

Jeff LaSala, the crazy person behind The Silmarillion Primer, won’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone. Tolkien geekdom aside, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He sometimes flits about on Twitter.