Lundy is a very serious young girl who would rather study and dream than become a respectable housewife and live up to the expectations of the world around her. As well she should.

When she finds a doorway to a world founded on logic and reason, riddles and lies, she thinks she’s found her paradise. Alas, everything costs at the goblin market, and when her time there is drawing to a close, she makes the kind of bargain that never plays out well.

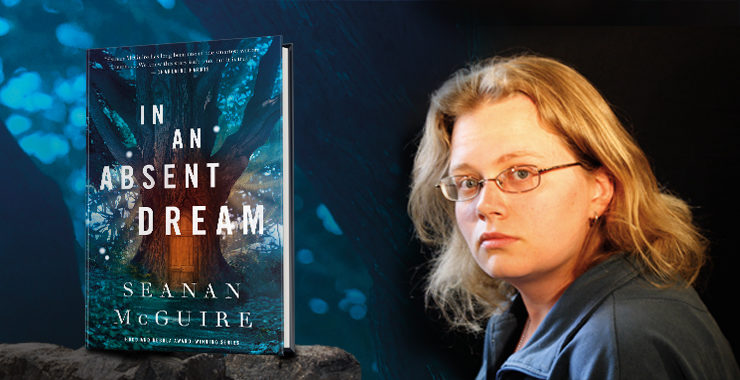

In an Absent Dream is a stand-alone fantasy tale from Seanan McGuire’s award-winning Wayward Children series, which began with Every Heart a Doorway. Available January 8, 2019 from Tor.com Publishing.

Chapter 1

A Very Ordinary Garden

1964

In a house, on a street, in a town ordinary enough in every aspect to cross over its own roots and become remarkable, there lived a girl named Katherine Victoria Lundy. She had a brother, six years older and a little bit wild in the way of boys who could look over their shoulders and see the shadow of a war standing there, its jaws open and hungry. She had a sister, six years younger and a little bit shy in the way of children who had yet to decide whether they would be timid or brave, kind or cruel. She had two parents who loved her and a small ginger cat who purred when she stroked its back, and everything was lovely, and everything was terrible.

Like the town where she lived, where she had been born, and where she was beginning to feel, in a slow and abstract way, that she would someday die, Katherine—never Kate, never Kitty, never anything but Katherine, sensible Katherine, up-and-down Katherine, as dependable as a sundial whittling away the summer afternoons—was ordinary enough to have become remarkable entirely without noticing it. Had she been pressed on the matter she might, after protesting that there was nothing remarkable about her, have suggested her own sixth birthday as the moment of the twist.

We must go back a little beyond the beginning, then, to learn; to observe. What are we here for, after all, if not for that? So:

Little Katherine, her mother’s belly round and ripe as a Halloween pumpkin, bulging with the impending harvest of her sister, sitting prim at the picnic table her parents have set up in the backyard. There is a cake, slightly lopsided, frosted in lemon buttercream that smells sweet and sour in the same breath, impossibly tempting and glittering with sugar crystals. There are gifts, a small pile of them, wrapped in brightly colored paper recycled from other birthdays, other holidays. There is her brother, twelve years old and eyeing the cake with a pirate’s hunger, ready to pillage its depths the second he is given leave. There are so many things here, paper streamers and smiling parents and the distant scent of bonfires burning in the fields. There are so many things that it would be easy to miss what should be obvious: to miss what isn’t here.

There are no other children. There is Katherine, and there is her brother, who has somehow already gotten frosting on the tip of his nose, and that is where it stops. As if to add insult to injury, the sound of laughter drifts over the fence from a neighbor’s yard, where half a dozen children from Katherine’s school have gathered to play. If not for the tempting lure of cake, her brother would already be out the gate and gone, off to join what sounds like a far better party.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

Her father, who is principal of the local elementary school, scowls at the fence but says nothing. He believes there is no malice in the timing of this event, that Katherine, overcome by the shyness that sometimes consumes children her age, failed to hand out invitations. He has even seen a few of them, ripped in half and stuffed into the kitchen garbage, where a cascade of eggshells and coffee grounds was not quite enough to hide them. He thinks this has nothing to do with him, with the way he enforces discipline and guides his students with a heavy, steady hand. After all, Katherine’s older brother had birthday parties, and they were well attended by his peers.

(The fact that he became principal two years ago, and that his son has not requested a party since, only the company of a few beloved chums and an afternoon at the movies or the carnival, does not occur to him.)

Her mother, who is so pregnant that her world has narrowed and widened at the same time, becoming a funhouse tunnel through which she must pass before she can be rewarded with a baby’s cry and the sweet simplicity of raising an infant, an innocent babe who will not yet share the trials and tribulations of the older children, has a better idea of what her husband’s job has meant for her daughter’s friendships. She remembers sweetly smiling children with sticky fingers, trailing along in a pack, Katherine never at the head or the rear, but somewhere in the comfortable, unremarkable middle. She remembers when they stopped coming around.

(She remembers, but she has a house to keep and a baby to bear, and somehow calling their mothers and finding back alleys into camaraderie has never been enough of a priority to nudge her into action. There are only so many hours in the day.)

The year is 1962. Katherine is six years old, two years after the doorbell stopped ringing in her name, two years away from the door we have come to see swing open. There is a choice here, hanging like smoke in the autumn air. She can cry for the friends she doesn’t have, mourn for the games she isn’t playing, or she can let them go. She can be the kind of girl who doesn’t need anyone else to keep her happy, the kind of girl who smiles at adults and keeps her own company. She can be content.

“Blow out the candles, Katherine,” urges her father, and she does, and she’s happy. She’s happy.

There: that wasn’t so difficult, and it mattered. Small things often do. A single pebble in the road can go unnoticed until it becomes stuck inside a horse’s hoof, and then oh, the damage it can do. This was a pebble; this was where things began the slow, stony process of changing.

Katherine walked away from her sixth birthday party with a smile on her face and the scent of lemon frosting clinging to her fingers, the ghost of sugar once enjoyed. She understood now, that the other children weren’t coming; that they would always be shadowy voices on the other side of a fence, refusing to let her through, refusing to let her in. She understood that she had, for whatever reason, been rejected from their society, and would not be readmitted unless something fundamental in the world chose to shift in its foundations, widening itself, rebirthing her into someone they could care for.

But she didn’t want to be someone they could care for. She didn’t want to be a Kate or a Kitty or even a Kat—all perfectly lovely, serviceable names, for perfectly lovely, serviceable people. People she already knew, at six years of age, that she didn’t want to be. She was Katherine Lundy. Her family loved her as Katherine Lundy. If the children in the yard next door or on the playground couldn’t find her worth loving the same way, she wasn’t going to change for them.

If this seems unusually mature for a child of six, it is, and it is not. Children are capable of grasping complex ideas long before most people give them credit for, wrapping them in a soothing layer of nonsense and illogical logic. To be a child is to be a visitor from another world muddling your way through the strange rules of this one, where up is always up, even when it would make more sense for it to be down, or backward, or sideways. Yet children can see the functionality of grief or understand the complexities of a parent’s love without hesitating. They find their way through. They deduce. Katherine had deduced, when the other children called her snobby or mean for not wanting them to cut her name short, when they had told her they couldn’t play with her because her daddy was the boss of their teacher and she would be a snitch someday, wait and see, that they weren’t going to change their minds about her.

Katherine was also, in many ways, a remarkable child. All children are: no two are sliced from the same clean cloth. It is simply that for some children, their remarkable attributes will take the form of being able to locate the nearest mud puddle without being directed toward it, even when there has been no rain for a month or more, or being able to scream in registers which cause the neighborhood bats to lose control of themselves and soar into kitchen windows. Katherine’s remarkability took the form of a quiet self-assuredness, a conviction that as long as she followed the rules, she could find her way through any maze, pass cleanly through any storm.

She was not the type to seek adventure, no, but she was well-enough acquainted with the shapes it might take. Shortly after the birthday where she had blown out the candles and made her choices, she discovered the pure joy of reading for pleasure, and was rarely—if ever—seen without a book in her hand. Even in slumber, she was often to be found clutching a volume with one slender hand, her fingers wrapped tight around its spine, as if she feared to wake into a world where all books had been forgotten and removed, and this book might become the last she had to linger over.

In the way of bookish children, she carried her books into trees and along the banks of chuckling creeks, weaving her way along their slippery shores with the sort of grace that belongs only to bibliophiles protecting their treasures. Through the words on the page she followed Alice down rabbit holes and Dorothy into tornados, solved mysteries alongside Trixie Belden and Nancy Drew, flew with Peter to Neverland, and made a wonderful journey to a Mushroom Planet. Her family was reasonably well-off, and there was no shortage of books, either through the shops or the library, which seemed to be entirely without limits.

Two years trickled by, one page at a time. Had she been someone else’s daughter, she might have found herself the butt of cruel jokes played by her peers, called “suck-up” or even the newly coined and hence still-cruel “nerd.” But her father was the principal, and the other children understood very well that the place for casual cruelty was outside his field of vision: the worst she was ever called where anyone might hear was “teacher’s pet,” which she took, not as an insult, but rather as a statement of fact. She was Katherine, she was the teacher’s pet, and when she grew up, she was going to be a librarian, because she couldn’t imagine knowing there was a job that was all about books and not wanting to do it.

No one ever asked if she was happy. It was evident enough that she was, that she had made her choices and set her courses even before she understood what they were, and if her mother sometimes wished that Katherine had more friends—or that she were more interested in babies than books, since it would have been nice to have some help around the house—she never said so. She loved the daughter she had, books and soft strangeness and rigid adherence to the rules and all. Katherine wasn’t lonely. That was all that mattered.

(Her father, it may be noted, wished nothing for his daughter, because he saw nothing strange about the way she was shaping herself, inside the soft walls of her upbringing. Her brother was playing peewee baseball and trading cards; her younger sister was talking and walking and doing all the other things one expects from a toddler trending into childhood. Katherine was quiet and biddable and studious and modest. Katherine didn’t run around with the wrong sort, tear her dresses or scuff her shoes. That this was because Katherine wasn’t running around with any sort at all seemed to escape him, tucked away with all the other things he didn’t want to think about. There were a surprising number of those. Like all adults, he had his secrets.)

At eight years old, Katherine Lundy already knew the shape of her entire life. Could have drawn it on a map if pressed: the long highways of education, the soft valleys of settling down. She assumed, in her practical way, that a husband would appear one day, summoned out of the ether like a necessary milestone, and she would work at the library while he worked someplace equally sensible, and they would have children of their own, because that was how the world was structured. Children begat adults begat children, now and forever, amen. She was in no hurry to reach those terrifying heights of adulthood; she assumed they would happen somewhere around the eighth grade, which was impossibly far away, and happened on the junior high school campus, where her father held no sway.

She wasn’t sure exactly what one was supposed to do with a husband, but she was quite sure her father wouldn’t want to be there when she did it, as he sometimes made dire comments about girls who played with boys while they were all at the dinner table, always followed by a smile and a comment of “But you would never do that, would you, Katherine?”

She had assured him over and over that she wouldn’t, even though logic stated that one day she would, since boys became husbands and normal women had husbands and he wanted her to be a normal woman when she was all grown up. Parents lied to children when they thought it was necessary, or when they thought that it would somehow make things better. It only made sense that children should lie to parents in the same way.

This, then, was Katherine Victoria Lundy: pretty and patient and practical. Not lonely, because she had never really considered any way of being other than alone. Not gregarious, nor sullen, but somewhere in the middle, happy to speak when spoken to, happy also to carry on in silence, keeping her thoughts tucked quietly away. She was ordinary. She was remarkable.

Of such commonplace contradictions are weapons made. Katherine Lundy walked in the world. That was quite enough to set everything else into motion.

Chapter 2

When Is a Door Not a Door?

The school bell rang loud and lofty across the campus, and the doors of the classrooms slammed open in euphonious unison as children boiled forth, clutching their schoolbags and their report cards in their hands, racing for the exits like they feared summer would be canceled if they dawdled too long. The teachers, who would normally have been demanding that they slow down, no running in the halls, indulgently watched them go. Some of it may have been the memory of their own school days, their own golden afternoons when the summer stretched ahead of them in an eternity of opportunity; some of it may simply have been exhaustion. It had been a long school year. They looked forward to the break as much as the children did.

In some classrooms, however, the teachers were looking at the students who hadn’t bolted for the door. The ones who couldn’t, due to braces on their legs or canes in their hands, who took more time to make the same journeys; the ones who were packing up their desks with exquisite slowness, giving their personal demons time to make their way off campus and into the hazy light of summer. And, in Miss Hansard’s second-grade classroom, the one who was still tucked in at her desk, peacefully reading.

“Katherine,” said Miss Hansard.

Katherine ignored her. Not maliciously: Katherine frequently didn’t hear her name the first time it was called, preferring to keep her nose in her book and continue whatever adventure she had decided was more interesting than the actual world around her.

Miss Hansard cleared her throat. “Katherine,” she said again, more firmly. She didn’t want to yell at the girl, Heaven knew; no one ever wanted to yell at the girl. If anything, she was grateful that Katherine was a pleasant, tractable bookworm, and not a hellion like her older brother. Teachers who found Daniel Lundy assigned to their classrooms frequently found themselves considering how nice it would be to retire early.

Katherine raised her head, blinking owlishly. “Yes, Miss Hansard?” she asked.

“The bell rang. You’re free to go.” When Katherine still didn’t spring from her seat and race for the door, Miss Hansard clarified, “It’s summer vacation. School is over for the year.”

“Yes, Miss Hansard,” said Katherine obediently. She bent her head back over her book.

Miss Hansard counted to ten before she said, somewhat annoyed, “I would like to lock my classroom and go home, Katherine. That means you have to leave.” In all her years of teaching, she had encountered every manner of slothful student—the lazy, the confused, the fearful—but she had never before encountered a student who simply refused to go when the final bell rang.

“My father can lock up when he comes to collect me,” said Katherine.

Miss Hansard paused. It was tempting to take the girl at her word—and since no one had ever caught Katherine in an actual lie, it would have been understandable for her to do so. Katherine didn’t lie; her father was the principal; her father was coming to collect her. It was an easy chain. Unfortunately, there was a piece missing.

“Is your father expecting to come and collect you from my classroom?” asked Miss Hansard. “It would have been polite of him to inform me, if so.”

“No, Miss Hansard,” said Katherine regretfully. She hunched her shoulders, reading faster.

Miss Hansard sighed. “So you simply assumed he would see the light on and find you here, at which time he would lock up, and I would get a disciplinary note for leaving one of my students unattended.”

Katherine said nothing.

“Up, please, Katherine. It’s time for you to go.”

Knowing when she was beaten, Katherine slouched to her feet, tucking her book into her bag, and started for the door. Miss Hansard sighed as she watched her go. Katherine really was an excellent student. A little reserved, and a little overly fond of looking for loopholes, but still, an excellent student.

“Katherine,” she called.

“Yes, Miss Hansard?”

“You were a joy to teach. Whoever has that opportunity next year will be very lucky.”

Katherine seemed to mull her words over for a while, considering them from every angle. Then she smiled. “Thank you, Miss Hansard,” she said, and slipped out, leaving the classroom suddenly, echoingly empty.

Miss Hansard, who had been teaching for nearly twenty years, slumped against her desk and wondered when retirement had gone from a distant impossibility to something to be devoutly yearned for. They got younger every year. She was certain of that much, at least. They got younger, and harder to understand, every single year.

The other students were gone, whirling off into the dawning summer like dandelion seeds in the wind. Katherine looked mournfully back at the classroom once before she started walking away. It would have been nice to spend a little longer at her desk, reading where no one knew how to find her. As soon as she got home, her mother would probably try to pass Diana off to her for “just a few minutes, be a good girl now and help your mother,” and that would mean playing babysitter for the rest of the afternoon. She didn’t particularly want to go outside and run around playing the sort of games that weren’t safe for toddlers, but she didn’t want to be stuck keeping Diana from eating thumbtacks, either.

Daniel never had to babysit. Daniel could have spent all day, every day reading in his room if he’d wanted to, and their parents would have been right there to applaud and tell him how amazing he was for being so serious about his studies. They didn’t discourage her, exactly, didn’t tell her she wasn’t supposed to read because she was a girl or that she needed to be better at her chores, but there was always a vague impression that they expected something different from her, and she didn’t know what to do with that. She didn’t want to know what to do with that. She suspected it would involve changing everything about who she was, and she liked who she was. It was familiar.

Dwelling on what would happen when she got home made her uncomfortable. She took her book back out of her bag and began to read, following Trixie Belden and her friends into another mystery. Mysteries in books were the best kind. The real world was absolutely full of boring mysteries, questions that never got answered and lost things that never got found. That wasn’t allowed, in books. In books, mysteries were always interesting and exciting, packed with daring and danger, and in the end, the good guys found the clues and the bad guys got their comeuppance. Best of all, nothing was ever lost forever. If something mattered enough for the author to write it down, it would come back before the last page was turned. It would always come back.

Katherine had made the walk home from school hundreds of times, tagging at her brother’s heels when she was in kindergarten, forging her own trail in first grade, and now following it with the faithful devotion of one who knows the way. She didn’t look up as she walked, allowing her feet to remember where they needed to fall if she was going to be home before dark.

It is an interesting thing, to trust one’s feet. The heart may yearn for adventure while the head thinks sensibly of home, but the feet are a mixture of the two, dipping first one way and then the other. Katherine’s feet were as sensible as the rest of her, trained into obedience by day after day of walking the same path, following the same commands. They knew where to go, and needed no input from her eyes. So it was truly an act of unthinkable rebellion when, at the corner of Pine and Sycamore, her feet—acting entirely on their own—turned left instead of right.

At first Katherine, deeply engrossed in her book and trusting in the inalienability of routine, didn’t notice the deviation. She continued walking as the familiar streets dropped farther and farther behind her, replaced first by the shabby neighborhood which bordered the creek, and then by an old walking trail that wound its way through a field of blackberry brambles. It was only when a shadow fell across her book, rendering it temporarily impossible to read, that she stopped and looked up, blinking at the unexpected absence of light.

In front of her, growing right in the middle of the path, was a tree.

Now, while this path was not a customary part of her journey home—was, in fact, some distance from any route she should have been taking—she had walked on it before, picking blackberries in the summer or using it as a shortcut to the local library. And there had never, on any of her journeys, been a tree there.

Katherine looked at the tree. The tree, so far as she could know or tell, did not look back, having no eyes to speak of. It was a good tree, the kind with branches that begged to be climbed and bark that should have been scarred with a dozen sets of initials, summer romances preserved for eternity in the body of a living thing. Its trunk was not a straight upward progression, but rather a long meander, a crooked line stretching from root to crown. She could not have closed her arms around it had she tried. Three girls her size couldn’t have accomplished that particular feat.

Its branches, which were thick and dense enough to block a remarkable amount of sunlight, were covered in leaves spanning the entire spectrum of green, from a pale shade that verged on soapy white all the way to a color that stopped barely shy of black. None of them seemed to be quite the same shape as its neighbors. It was a patchwork, an impossible thing. Katherine took a step back.

“What kind of tree are you?” she asked—for, as a child who spent the greatest part of her time in comfortable, unchallenging solitude, she had never quite lost the habit of speaking to herself when there was no one else around to talk to.

Had the tree responded with words, this would have been a very brief tale. Katherine, being a sensible girl, would have screamed and run for home, and never again allowed her feet to follow an uncharted trail into the fringes of mystery. She would have grown up stolid and silent, and found the husband she had once believed the world would conjure for her, and become the librarian she had always wanted to be. Her own children might have been more adventurous in their day, for it sometimes seems as if adventure can skip a generation, choosing to remain unpredictable and hence unchained.

Yes, had the tree responded with words, we would be finished now, and all the things which are set to follow would never have come to pass. Perhaps that would, in a way, have been the kinder outcome. Perhaps it would have spared a few broken hearts, a few shattered dreams. But the tree, which had been asked that same question before, did not reply aloud. Instead, the trunk twisted, like a washcloth being slowly wrung dry by an unseen hand, and a door worked its way into view while Katherine stared with wide and disbelieving eyes.

Her book fell from her suddenly nerveless fingers, landing in the dust of the trail. This will be important later.

The door in the tree was neither large nor ornate, but barely big enough for a child of her size to climb through, should she choose to do so. The hinges, the frame, even the doorknob, all were made of wood, stripped of its bark and gleaming pale as bone in the thin summer sunlight which filtered down through the branches. At the center of the door, exactly where her eyeline fell, someone had carved a square made of branches and vines, blackberry for the bottom, grape for the sides, and pomegranate for the top. All of them dripped with heavy, wooden fruit, at once crude and so realistically rendered that her mouth watered with a sudden, inexplicable hunger.

Inside the square, surrounded by fruit and contained by the graven border, were two words:

Be Sure.

“Be sure of what?” asked Katherine, who would have run had the tree chosen to speak, but who was still a child, after all, and an imaginative, remarkable child beside. The movement of the tree had not startled her as it would have an adult. The world was filled with things she did not quite understand, and she knew that plants could move: the progress of the zucchini across her mother’s garden proved that. So who was to say that a tree might not move, if given the right motivation?

That she should be the right motivation was flattering, in a deep-down, inexplicable way. She had never really considered herself to be worth that sort of attention.

The tree didn’t move again. The door didn’t open. It remained exactly as it was, tantalizing and strange, with those two little words—be sure? Be sure of what? She was sure of her skin, of her self, of her name, but somehow she didn’t think that was what the tree intended—hanging in front of her eyes, an unanswered question that contained absolutely everything.

Katherine took a step forward, one hand reaching thoughtlessly outward, until her outstretched fingertips were barely an inch from the wood. The carved fruits seemed to shimmer, like they had been coated in a thin layer of dew. She wanted to touch them more than she wanted anything else in the world . . . and so she did, brushing her hand across the image, feeling the soft warmth left by the summer sun. The shimmer remained, but the wood itself was dry as a bone.

Again, had she been older, Katherine might have seen this for a warning. Wood does not customarily glitter. Few things do, unless they are attempting to lure something closer to themselves. Sparkle and shine are pleasures reserved for predators, who can afford the risk of courting attention. The exceptions—which exist, for all things must have exceptions—are almost entirely poisonous, and will sicken whatever they lure. So even the exception feeds into the rule, which states that a bright, shimmering thing is almost certainly looking to be seen, and that which hopes to be seen is pursuing its own agenda.

The doorknob turned, entirely on its own. Not all the way, not enough to undo a latch or open a door, but . . . it turned all the same, a little half-twist that drew Katherine’s eyes away from the carving and down toward the motion. If the doorknob could turn, it wasn’t locked, she realized.

The door could be opened.

No sooner had the thought formed than it became the most important thing she had ever considered. The door, the mysterious door with its mysterious admonition, could be opened. She could open it, and see what was on the other side. Why, perhaps she could even meet the person who had instructed her to be sure, and tell them that she was Katherine Lundy, she was always sure, no matter what. Hadn’t she survived four whole years of school without any friends? Couldn’t she read faster than anyone else she knew? She was always sure.

The only thing she wasn’t sure of was why she was hesitating. She looked at the words again, etched deep into the wood. This was no pocketknife carving, done by one of the tough teenagers from the high school on the other side of town. This was beautiful. Her mother would have been happy to hang something that beautiful in the hall, and her father wouldn’t have sniffed when he saw it, rejecting it as a childish art project. This was real, in a hard-edged, intangible way she didn’t have the vocabulary to articulate, but understood all the same.

Be sure. She only had one chance to decide whether or not she was. She knew that. She didn’t know how she knew, but she knew all the same.

“I am sure,” she said, and grasped the knob. It spun in her hand, eager to fulfill its purpose, and the door swung open, soft white light flooding out into the shadows beneath the tree. Katherine stepped through. The door slammed shut behind her.

For a moment, everything on the trail remained the same. Then, like a patch of dust being broken up by the wind, the tree began to fade away, turning golden as the sunlight that lanced through its now-insubstantial branches. The solid wood dissolved into tiny dancing motes of light, until those too were gone, and only the ordinary, unblocked trail remained.

The trail, and Trixie Belden and the Black Jacket Mystery, which had fallen face-down in the dirt, forgotten in the face of a greater mystery.

It would be several hours before the Lundys realized Katherine wasn’t holed up in her room, reading and hoping to avoid her chores. It would be another hour after that before Daniel returned from his survey of her usual hiding spots—the creek, the trees behind the school, the swing set at the local park—and reported that she was nowhere to be found. The police would be called, the town would be alerted, and sometime after that, the book would be found, opened, identified as hers. The search would begin.

But not yet. Here and now, there was only the trail, the book, and the absence of the tree.

Everything else would come later.

Excerpted from In an Absent Dream, copyright © 2018 by Seanan McGuire.