Wherein the Dúnedain Are Made Better, Stronger, Faster, and Are Gifted With Huge Tracts o’ Land…and It Just Might Not Be Enough

In The Silmarillion, we don’t spend quite enough time in the Second Age to really get to know it—a chapter and a half, at best. And rather than walk through what does follow the First Age chronologically, Christopher Tolkien—who curated all of this for us after his father’s death—presents the next two ages of the history of Middle-earth in two basic pieces. Each overlaps the other but centers on its own events.

The first of these is the Akallabêth, a word that means “the Downfallen,” and specifically refers to the figurative and literal sinking of Númenor. You can always count on J.R.R. Tolkien to tell you something falls before he tells you it’s even a thing. Well, Númenor was a thing, and even casual readers of The Lord of the Rings will already know a thing or two about it. This is a phase of the book when Men finally take center stage, while Elves merely flit in from the wings once in a while.

While this is not a difficult story to follow, the gauntlet of both Elvish and Adûnaic (i.e. Númenórean) names can trip you up. Don’t let it! Sauron WANTS you to fall. Given the big ideas in this section, I’ll be tackling the Akallabêth (ah-CALL-la-beth) in two parts, which mostly amounts to the great rise and the watery fall of Númenor.

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Elros (Tar-Minyatur) – Half-elf, first King of Númenor, Elrond’s twin

- yadda

- yadda

- yadda, an extensive succession of kings and queens of Númenor

- Ar-Pharazôn – Man, last King of Númenor, jerkwad-in-chief

- Sauron – Maia, Assistant to the World’s Greatest Asshole

Akallabêth, Part 1

The opening sentence in A Tale of Two Cities could easily apply to the Second Age of Arda. Some wonderful things are afoot, as are some grievously terrible things. There is enlightenment and there is darkness, hope and despair. Remember that Men first awoke during Middle-earth’s event horizon, which marked the beginning of the long decline of the Elves. It’s not yet time for the dominion of Men, but this is at least square one. And what a dark square it is.

In a nutshell, Men first fell under the influence of Morgoth not long after their awakening. This was back when the Great Asshole of the World was largely holed up in Angband but he could still go afield in Middle-earth, and certainly sent his “shadows and evil spirits” out to do his dirty work. And somewhere offstage, where no one was writing any of it down, our own short-lived yet inscrutable race experienced its first fall—that is, some mysterious Kinslaying-level event that marred us. Even worse, we Men came to fear the “gift” that was given to us.

The gift of death, that is, which was first called the gift of Ilúvatar to Men—a release from the world and all its troubles, to a fate beyond the Circles of the World “whither the Elves know not.” And we, as Men, certainly know not. And you know who else knows not whither? The mighty Valar! Now, maybe Manwë—who seems to have the highest security clearance in all Eä—has glimpsed a memo or two because he “knows most the mind of Ilúvatar,” but if he’s got any intel, he’s not telling.

The main point is, Men seem to have a purpose, both for being on Arda for a little while and then for going somewhere beyond it. But we just don’t know what it is. Existence, amirite?! Morgoth, who hated Men as he hated all things he didn’t himself make, gave death a new spin—a dark and scary spin. Which isn’t surprising. If Men get to escape him, Morgoth at least wants them to freak out about it before they do. And if he can harness that fear in order to manipulate them, so much the better.

And so it was from this shadow of Morgoth that a sizable group of Men originally fled westwards and ended up in Beleriand, only to one day meet Finrod, the most neighborly of all Elves. And it was there that they became the Edain, the Elf-friends. Though the Edain were painfully whittled down over time to just a fraction of their original numbers, that fraction sided with the host of the Valar during the War of Wrath when even the mighty Noldor stood on the sidelines.

Well, as we know, Morgoth got his ass neatly handed to him. The host of the Valar was victorious, with the help of Men and the Eagles of Manwë. And even the sky-sailing Eärendil, who now lives on with a unique purpose of his own amid the stars as the brightest one of all. Morgoth got booted out of all Arda, and the curtains dropped on the First Age.

So here at the onset of the Second Age, most of the Eldar now sail—many for the first time!—into the West, to the Undying Lands. That’s a Mannish term that refers to the continent of Aman, mostly the lands inhabited by the immortals: Valinor itself, Eldamar, and the island of Tol Eressëa. Eressëa is where Beleriand’s Elven survivors were summoned to; so for the most part, that’s where they’re settling, not in Valinor proper (though one imagines visiting there may be fine).

Those who stayed on Middle-earth have mostly drifted east across the Blue Mountains to settle in Eriador—with the exception of important Elves like Galadriel, Gil-galad, and Círdan the Shipwright, who have settled in Lindon with their people. Even the bad guys who survived the War of Wrath have migrated to the east and scattered to the winds—some Orcs, definitely some dragons, wolves and other “misshapen beasts,” probably some trolls, and scads of not-so-nice Men. And while there is no longer any organized evil on the scale of Morgoth’s reign, there is yet plenty of unorganized evil. The Men who fought for Morgoth no longer have his lash at their backs, so they’ve just set themselves up as petty warlords, ruling over the scattered and untamed peoples who never had any allegiance any which way. In general, it’s a shitshow for most mortals: a dark and wild age where it’s just wildernesses and monsters, monsters and wildernesses.

So what of the Edain, the mortal Elf-friends who fought on the right side of history? The Valar have decided to reward them for their valor in a two-step plan: (1) teach them how to be awesome, then (2) give them some awesome lands to be awesome in. Eönwë himself, herald of Manwë and arguably the mightiest of the Maiar—the dude who led the charge in the war against Morgoth—now goes among the Edain and instructs them. This is nothing to sneeze at. Except for a couple of exceptional mortals, Men have never spent any proper face time with any of the Ainur—those timeless beings that Ilúvatar thought up at the start of all things and who know deep facts about, well, all existence. Elves have chilled with both Maiar and Valar, sure, but that’s Elves for you. Men are the Strangers, the Followers, the Guests in Arda who are only meant to be here for a limited time. Eönwë’s attention is a really big deal, and it levels up the Edain big-time.

Next, the Valar and their helpers prepare for them a place far removed from Middle-earth—in fact, not terribly far from (and one might argue, not far enough from) Tol Eressëa, the Lonely Isle, and Aman itself. And so now they’re going to be called the Dúnedain, i.e. the Edain of the West. This tutelage and relocation comes with major benefits, and it’s going to mean wonderful, far-reaching things for all of Middle-earth…but will also lead to some grave temptations.

Now, in all that follows, remember that Ilúvatar knew that Men would inevitably be irresponsible and not use their talents wisely, at least a lot of the time. He even once said, as a sort of echo to what he told Melkor:

These too in their time shall find that all that they do redounds at the end only to the glory of my work.

Of course, we know that. And the Valar, too. But presumably not Men. So anyway, the Valar do another team-up project like in olden days, with the Lamps, the Two Trees, and the Sun and Moon. But this time, it’s just a single (if glorious) island cooked up just for the Dúnedain.

It was raised by Ossë out of the depths of the Great Water, and it was established by Aulë and enriched by Yavanna; and the Eldar brought thither flowers and fountains out of Tol Eressëa. That land the Valar called Andor, the Land of Gift; and the Star of Eärendil shone bright in the West as a token that all was made ready, and as a guide over the sea; and Men marvelled to see that silver flame in the paths of the sun.

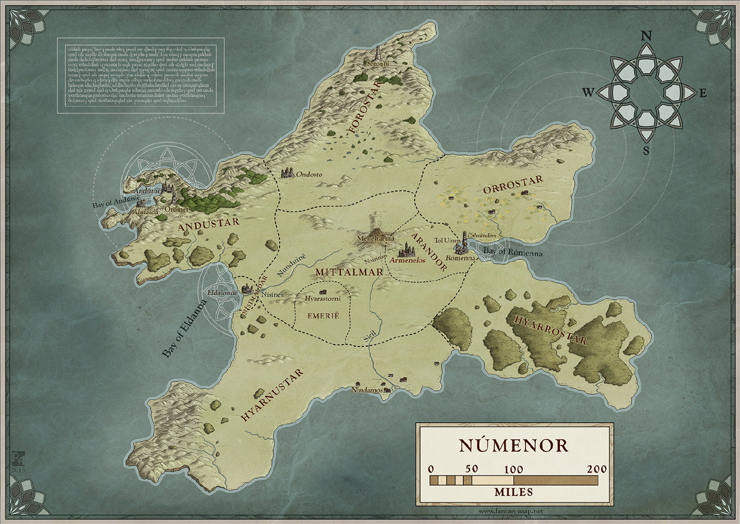

It’s really some amazing real estate, this gigantic chunk of the deep sea floor that’s been yanked up and repurposed, furnished with a fruitful, verdant landscape. It’s like Little Valinor but catered specifically for Men, a marvelous island on the Great Sea with the best views all around—quite a lot smaller and minus the whole “deathless shores” thing. This is the place commonly called Númenor, which the Elves call Númenórë and the Men themselves call Anadûnê (of the West”). Or Westernesse in their own language, Adûnaic.

And that’s a word all readers of The Lord of the Rings will have come across a few times. Gandalf refers to it when telling Frodo the history of the One Ring and how Sauron came to lose it, cut from his hand by Isildur of Westernesse. Tom Bombadil also gives the hobbits daggers of Westernesse make from the treasures of the barrow-wights, “long, leaf-shaped, and keen, of marvellous workmanship, damasked with serpent-forms in red and gold,” which later Aragorn refers to being “wound about with spells for the bane of Mordor.” One such dagger upstages the rest when Merry sticks it into the back of the knee of a certain “foul dwimmerlaik.” And those daggers weren’t even made in Númenor but in after-days by Men of Númenor.

And as for the Dúnedain themselves—who we can now also rightly call Númenóreans—their friendship with the Valar and the Eldar has paid off. Through mere association with these immortals, starting with Eönwë, and now from living in this splendiferous, Ainur-fashioned island, they receive longer lifespans, greater wisdom, and greater physical stature. According to Unfinished Tales, Tolkien regarded the average height of Númenórean dudes in these elder days to be six feet four inches. These are seriously tall folks!

Even “the light of their eyes was like the bright stars.” Indeed, they’re very Elflike in these things, but—and this is a big BUT—they’re still mortal. They’ll still die when their lives are spent, or if they’re done in with violence or suffer some freak accident, because the gift of Ilúvatar cannot be withheld from any Man. That said, they’ve got the best healthcare plan any mortal can have, for “they knew no sickness, ere the shadow fell upon them.” Given the name of this part of the book, that’s not much of a spoiler. There’s always a shadow coming.

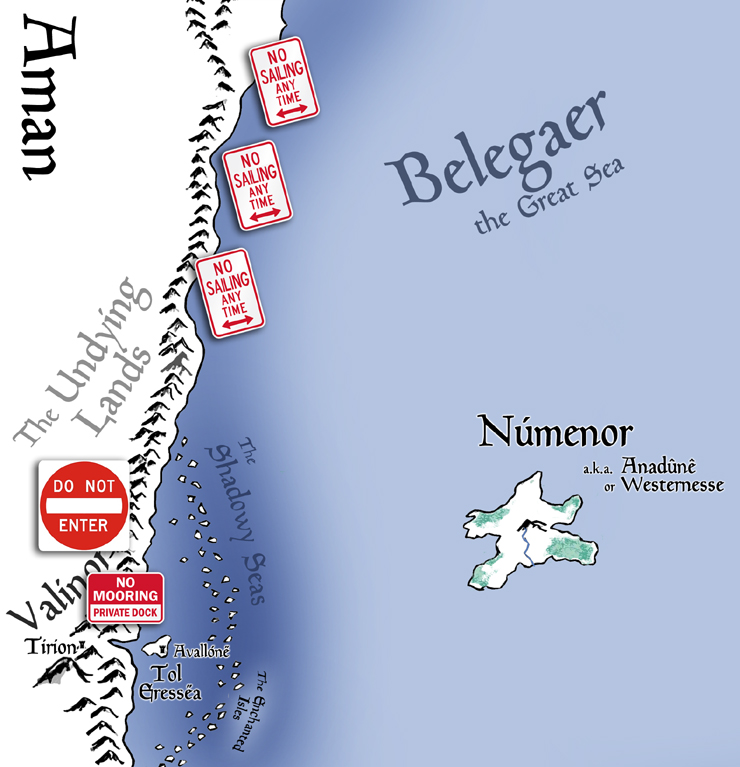

For all the gifts given to the Númenóreans, there’s one condition, one rule, they must abide by: don’t talk about Númenor. Never, under any circumstances, are they to go to that distant, gleaming city in the west that they can spy with their sharp Númenórean eyes. That port is, in fact, Avallónë (ah-vah-LONE-ay), city of the Eldar on Tol Eressëa where the Teleri dwell along with all those Elves who left sinking Beleriand.

Strictly speaking, the Númenóreans are not to sail so far west that that they can’t see Númenor anymore. That’s all. They can go anywhere else if they want to. Númenor isn’t a prison; they can come and go as they please—just not any further to the west. The world is a big place.

This ban on going to Aman is Manwë’s decree and is meant for their protection, so that these ennobled Men don’t become “enamoured of the immortality of the Valar and the Eldar and the lands where all things endure.” The Númenóreans don’t really understand this—and yeah, the Valar should probably have explained it better up front—but these long-lived mortals are generally okay with the arrangement. They’ve got so much going for them already! Who wants to live forever anyway?

But these are the good times. In fact, upon Númenor’s central mountain of Meneltarma, a place sacred to Ilúvatar himself is observed by the Dúnedain. It’s not really a temple, just a hallowed and flatted summit open to the sky—a place of silence and reverent gatherings—but it’s still the closest thing we’ve seen to traditional religious observance in the book! Meanwhile, at the base of the mountain, tombs are built for Númenor’s kings.

Now, in these early days, Eldar from the Undying Lands also come to visit their Dúnedain friends, bearing gifts and, being Elves, are probably intent on naming everything new they see. Look how cool this island is! These Dúnedain sure have some pretty sweet digs! But note, these Eldar are not to be confused with the ones who stayed on Middle-earth, such as Círdan the Shipwright, Elrond, and the old Noldor gang (Gil-galad, Galadriel, Celebrimbor, etc.). Rather, these will be Teleri Elves from Tol Eressëa or other Noldor who’ve settled there. And gosh, since there are Teleri involved, “sailing in oarless boats” with white birds all around them, there’s no way they’re not talking shop with Númenor’s own shipwrights and seafarers. We’re talking the best mariners among Elves hanging out with those who are fast becoming the best mariners among Men!

Anyway, one housewarming present they bring their mortal friends is a young seedling from the White Tree on Tol Eressëa, which itself grew from a seedling of the one Yavannah herself gave to the Noldor in old Tirion upon Túna. Thus a White Tree, named Nimloth, is planted in the courts of the Númenórean kings. A familiar motif, isn’t it?

This now becomes a living symbol of Númenor’s royalty, and maybe more specifically as it pertains to respect for the Eldar. And speaking of royalty, the first king of Númenor—and the one whose descendants will carry the line of kings—is Elros, son of Eärendil and Elwing. He’s actually appointed to this role by the Valar, so this is as close to divine right as you’re gonna get in Middle-earth, though it carries none of the wicked baggage of our real world history. As a Half-elf, Elros was allowed to choose either Team Elf or Team Man when it came to cosmic counting. Presumably after a very emotional conversation with his twin brother, Elrond, he chose to be mortal. So death is on his eventual agenda.

But still, as a Half-elf he still lives exceptionally long, longer even than the otherwise long-lived Númenóreans. He even takes on the bad-ass name of Tar-Minyatur (meaning “High First-Lord”), establishing the custom of using Quenya for each king’s title. Sadly, we know nothing at all about his wife (who I can’t help but think must have been a factor in his decision to be mortal), but they have some kids and it’s worth noting that those kids are fully mortal. The son or daughter of a Half-elf isn’t necessarily considered Half-elven. Thus all the descendants from here on out are fully mortal, if long-lived; those Elf-genes do carry on.

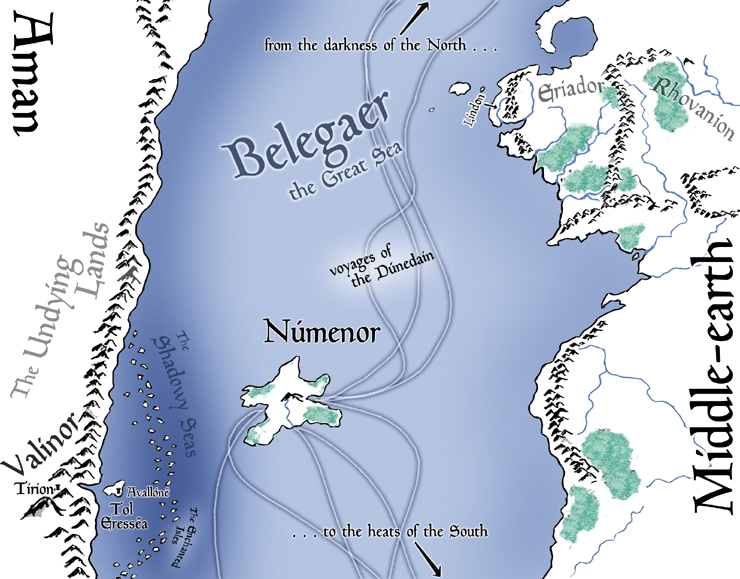

Now, Númenóreans excel at just about everything they set their minds to: crafting, forging, writing, artistry, ship-building, sailing, pretty much anything you could earn a merit badge for. You name it, they’re good at it. But especially the seafaring. And since sailing westward is a big no-no, they sail pretty much everywhere else. Well, not exactly back to Middle-earth again . . . at least not yet. Rather, they explore far, far afield, reaching the fringes of the not-yet-spherical world itself:

from the darkness of the North to the heats of the South, and beyond the South to the Nether Darkness;

The Nether Darkness?! That’s a nebulous region, indeed—one that Tolkien never properly identifies, and it seems to be a point so far from everything else that the Sun doesn’t even illuminate it. In short, these Men basically Magellan the bejesus out of Arda! If they did nothing else, the Númenóreans’ oceanic exploration of this apparently flat world would still make them legendary. Not only do they circumnavigate the other continents and go amid the “inner seas,” they even spy from afar the Gates of the Morning! That’s the fabled place in the uttermost east where the Sun re-enters the atmosphere from beneath the world. I don’t think even Elves have done that. Elves love the world so much they tend to get attached to portions of it; Men, by contrast, seem to be more subject to wanderlust.

So, for a very long time, things are great. I mean, for the Númenóreans.

Meanwhile, over in Middle-earth, they’ve got a dark age going on; there, the Secondborn Children of Ilúvatar have been regressing under the management of petty lords and the marauding (if leaderless) monsters that came out of Morgoth’s breeding programs long before. Yet by the time of the third king of Númenor, now five hundred years into the Second Age, our old friend Sauron finally crawls out from under a rock. Yup, it turns out he’s just been lying low on Middle-earth. You know, not submitting himself to the judgement of Manwë, as Eönwë had commanded him. Shocking, I know.

Yet it’s not until the fourth king of Númenor—now five hundred sixty-eight years since the Dúnedain sailed west to their fantasy island at the invitation of the Valar—that the Númenóreans send ships back to check up on those lesser Men* back east. Bear in mind that while this is just a few generations of Dúnedain later, for all those mortals on Middle-earth, some twenty or thirty generations will have passed. The Númenóreans may as well be an ancient myth now (like fabled Atlantis), so when they show up in their technologically-advanced ship, these civilized overachievers—these enlightened, highly-equipped, not to mention tall-as-all-get-out Men—seem godlike in stature.

*By the way, we do sometimes see the term “lesser men” pop up elsewhere in the legendarium. Don’t read worth into this. It speaks to people of lesser strength, stamina, and skill of body and mind—usually of birth, of circumstance. Just as there are both Calaquendi and Moriquendi, the former being generally more physically powerful for having dwelt in the light of the Two Trees of Valinor. Not to mention the Eldar who are somewhat distinct from the Avari (the Unwilling Elves who didn’t answer the summons of the Valar). Heck, Thingol’s people once confused them with Orcs, thinking them Avari who had “become evil and savage in the wild.” Awkward! The bottom line: there is no suggestion of any higher cosmic status for any Men who are “greater” at birth. While Tolkien may have created memorably heroic characters among those of “high” lineage, like Aragorn for Men or even Frodo for hobbits, those of “lesser” class or race are not of intrinsically smaller worth. The best proof: Samwise Gamgee, who many rightly consider one of the greatest heroes in The Lord of the Rings.

Well, when these giant-sized “Sea-kings” do make contact with them, the Men of Middle-earth are “weak and fearful” by comparison, still living in the figurative gutter of Morgoth’s legacies. The Númenóreans could easily just take over at this point, but they don’t. They have no desire to. They’re Men of peace, friends of the Eldar, and they use their enlightenment to help out their troubled brothers and sisters. They feel bad for them. Therefore the Númenóreans share the mental wealth, such as they can, proverbially teaching these Men to fish rather than giving them fishy handouts.

Then the Men of Middle-earth were comforted, and here and there upon the western shores the houseless woods drew back, and Men shook off the yoke of the offspring of Morgoth, and unlearned their terror of the dark.

The Númenóreans don’t really stick around, though. They bring their friendship, give some great pep talks, show off their mad skills (but humbly), then jump back in their ships and sail back to the west, where they’re always yearning to go. Always.

But sadly, this practice doesn’t last forever. Their pining for the west extends to the Uttermost West, to the Undying Lands—the one place they’re specifically not supposed to go. And just as the short-lived Men of Middle-earth had largely forgotten those legendary Edain who sailed away early in the Second Age, so, too, do the Númenóreans seem to forget the origins of their abundance—willfully, it seems. They’re beginning to take what they’ve got for granted. Sure, they’re rich, but they could be richer, right? Yes, they live long for Men, but couldn’t they maybe live longer? I mean, c’mon, those Eldar never die at all. What’s up with that?

Despite the lushness of their own island, suddenly it’s like the Númenóreans are wondering if the grass on Tol Eressëa is greener than their own. It probably is! They’re yearning, and curious, and antsy…but for a long time, that’s all.

For some perspective, at this point it’s been more than six centuries since the peoples of Middle-earth had to buy all new calendars (for the First Age/Second Age changeover). This age has already seen more years than the first one, at least those counted since the rising of the Sun. All those sagas of the exiled Noldor and their wars against Morgoth; of Beleriand and its kick-ass realms; and of the tales of Beren, Lúthien, Túrin, and Tuor…that same amount of time has gone by again and then some. For the Númenóreans, peace and prosperity endures long before its eventual decline. So there is that.

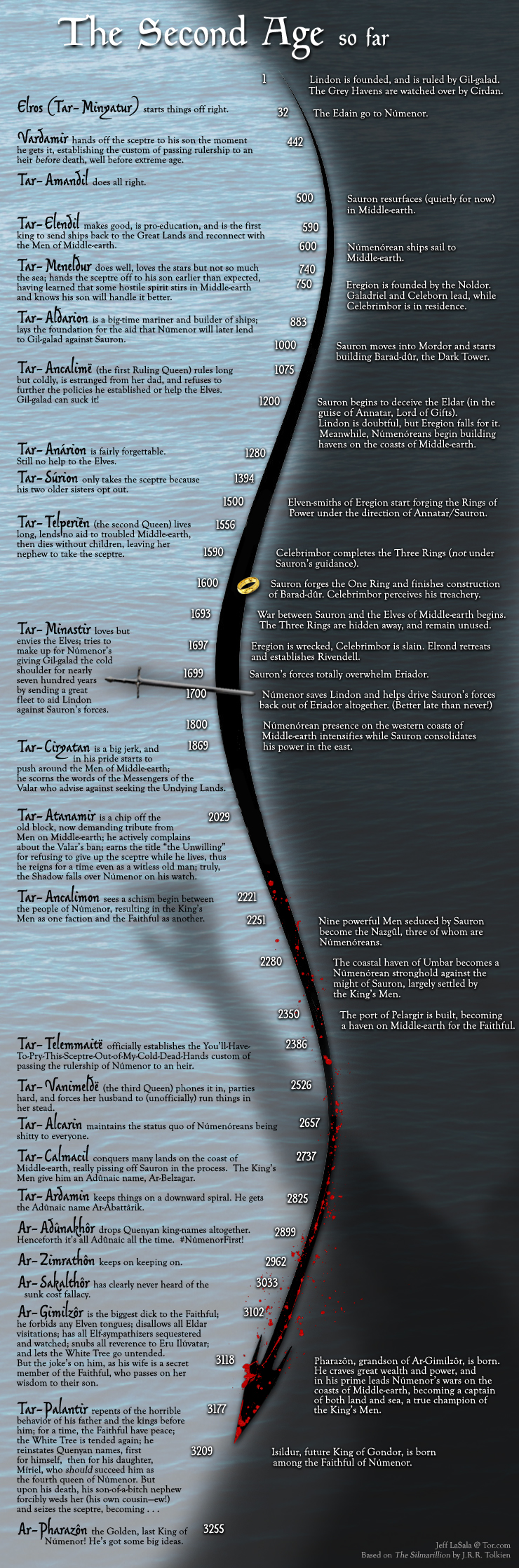

Eventually, the Akallabêth moves into a sort of “Abraham begat Isaac” sequence wherein we get a progression of kings and queens. It’s not exactly boring, but it can be a bit of a blur on the first go-round. On subsequent reads and with a passing familiarity with just some of the names, however, you can really feel the moral decline, the increasing anxiety, the ever-encroaching desire for ever more power even as they grow mightier as a kingdom.

Of course, it’s not all bad. After the Númenóreans start helping out the so-called lesser Men of the mainland, coming and going on their ships, they also renew their friendship with those Elves on Middle-earth who didn’t go back to Valinor. But only intermittently, depending on who happens to be king or queen in Númenor at the time. We’re talking about those of the Eldar who stayed in Lindon and along the coasts to fight “the long defeat,” as Galadriel will one day describe it. Gil-galad is their main point of contact, and it’s from him that they’ll eventually learn about the threat of Sauron.

And in fact, it’s by the time of the sixth king of Númenor, in the year 1000, that Sauron starts to take the growing might of the Númenóreans seriously. He chooses a vast section of largely uninhabited real estate south and east of the Misty Mountains to make his Land of Shadow. Enter Mordor! And you know, he simply walks in, sets up shop, and starts to build Barad-dûr, the Dark Tower. A fine place to build up his own future empire.

Say, you know who’s already there in the mountains surrounding Mordor? The last child of Ungoliant, Shelob the Great, who long before escaped the ruin of Beleriand. And by this time she will have expelled some nasty-ass broods of her own up in that region of Middle-earth called Rhovanion, which just happens to contain a big forest, Greenwood the Great, that will one day be renamed (as all things are in Tolkien!) to become Mirkwood. It’s all starting to fall into place.

But anyway, this chapter is about Númenor, so let’s get to those monarchs, shall we?

Now, there’s absolutely no need to memorize any of these names for comprehension. They’re not half as important as it was to know your Fingons from your Finrods in the earlier, Elf-centric chapters of The Silmarillion. But for a good sense of how many kings (and three queens) governed Númenor, and enacted, shifted, or reversed its policies—not to mention just observing the moral zigzag—I present the following list.

But do note a few things up front:

- The King’s Men is that faction of Númenóreans who become especially proud and jealous, not to mention fiercely loyal to those kings most chafed under the Valar’s ban. They’re essential a vocal political party. But in time, a bunch of them will settle permanently on Middle-earth and go down in history as the Black Númenóreans (like the Mouth of Sauron).

- The Faithful are those Númenóreans who still want to be Elf-friends. They try to keep the memory and friendship of the Eldar alive, keep the White Tree flowering, and ultimately respect the ban of the Valar. As time goes by, the Faithful become marginalized by the King’s Men.

- The Sceptre is the ruling king’s or queen’s staff of office. When it’s passed from one monarch to another, so does rulership of all Númenor.

This information is largely drawn from The Silmarillion itself, the Appendices from The Lord of the Rings, and “The Line of Elros: Kings of Númenor” from Unfinished Tales.

Through the long millennia, between the time of founder Tar-Minyatur and the egomaniacal Ar-Pharazôn, pressure builds beneath the surface of Númenor. Its people, who have so much already, find that they still want more. They yearn to sail west, to set foot on the one place that’s off-limits, to taste that forbidden fruit. Surely in the Undying Lands they can shrug off this pesky thing called death? Why, they’re the mighty Men of Númenor! Why should they have to die, after all, like those other inferior mortals over on Middle-earth? Weren’t the Dúnedain supposed to be special or something? What gives?

By the time of the thirteenth king, Tar-Atanamir (halfway to Ar-Pharazôn himself), when these yearnings have turned to murmurs and then into grumbles, the Eldar who visit them take notice. They then report this begrudging of the “doom of Men” back to the Valar directly. And it’s a buzzkill for Manwë, as he can see where this is going. This is what he’d hoped to avoid—if they see too much of the Blessed Realm of Aman, they’re going to want it for themselves and think they can somehow subvert the gift of death.

But all right, sure, it’s been a long time since representatives of the Valar had a heart-to-heart with the Dúnedain. So Manwë sends messengers to speak on his behalf, not only to reason with the current King of Númenor and his people, but even to come clean a bit. These messengers might be Eldar themselves, but they might also be Maiar (it’s unclear). The conversation goes something like this, and I might be paraphrasing:

Messengers: “I’m sorry, but only Ilúvatar can change the rules concerning big things like death. Even if you could make it to Aman, it wouldn’t give you any more life. It’s not you, it’s us. Which is to say, it’s not the place, it’s the people, that make the deathless shores deathless. Manwë needs you to stay away for your own good—same reason we couldn’t all just come hang out on Númenor, we Eldar, Maiar, and Valar. You’d only age faster and die the sooner.”

Númenóreans: “Umm, wasn’t Eärendil himself mortal at the start? He’s our ancestor, isn’t he? Yet he can just chill in your land, can’t he? How interesting.”

Messengers: “All right, yes. He can; an exception was made because…reasons. But notice Eärendil isn’t allowed back on your lands? You guys are Men, and you’ve been designed by Ilúvatar to be just as you are. You seem to want to have your cake and eat it, too, and be like both Men and Elves, to come and go as you please. It just can’t be that way. And by the way, even if the Valar wanted to, they can’t just take away the gift that Ilúvatar gave you. Think of it like a ticket. A one-way ticket out of this whole world, to somewhere beyond that only Ilúvatar knows about. Even the Elves can’t do that; they’re stuck here in Arda for the long haul, for good or ill. I mean, really, who should be jealous of who?”

Númenóreans: “Uhh, we have it worse because we get old and wrinkly and then die. Die. We go somewhere special, you say? Well, do you know where that is? Sure seems convenient that you don’t know. And hey, we also like the Earth we live on; that’s why we want to keep living and enjoying it. Is that so wrong?”

Messengers: “It’s true, we really don’t know where you go when you die. Guess who else doesn’t know: the Valar! That’s right, you’re going to find out what’s behind Ilúvatar’s curtain before even the great powers of Arda do! Your true home is out there; you’re just guests in this world. It’s only because you bought into Morgoth’s lies long ago that you’re now so afraid of death. And if you’re afraid, that might mean his shadow grows again in you. And that’s something we’re afraid of! So, please be careful. You can’t change the rules. We can’t change the rules! You’ve been trusted with great power for your race; don’t let that become your Waterloo.”

Númenóreans: “Our what now?”

Messengers: “Err, your downfall. There’s a reason you love this Earth but there’s also a reason you’ll soon leave it. Trust in Ilúvatar and have patience.”

Númenóreans: (grumbling under their breath) “No, we want gratification now. We want not only the power and longevity we already enjoy compared to other Men, we also want assurances for immortality beyond it all. So no, we’re through with dying. We want to live forever, too!”

And so, dissatisfied with the messengers’ words, the Númenóreans at large continue to stew in their discontent. Thus the King’s Men and the Faithful grow out of this moral divide. The Elf-friends mostly just dodge persecution, while the far more populous King’s Men land more and more often in Middle-earth, taking there what they will, becoming subjugators, not teachers or helpers. Conquerors. The Númenóreans are becoming like the evil Men who were under Morgoth’s sway long ago, but way more powerful, way more organized. The haven of Umbar is established as the launching point of their conquests. Some time later, the haven of Pelargir is established further to the north, and is a place for the Faithful to dwell and make further contact with Gil-galad and the other Eldar in the northwest corner of Middle-earth.

And then the twenty-fifth King of Númenor steps up, Ar-Pharazôn the Golden, and he’s a real piece of work. Say, wasn’t old Glaurung also called the Golden? Hmm.

In the next installment, we’ll talk about the second half of the Akallabêth, find out if the Dúnedain can turn things around, and discover whether Ar-Pharazôn can make Númenor great again!

Top image from “Secret haven of Númenor” by Giovanni Calore.

Jeff LaSala won’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone. Tolkien geekdom aside, he wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He is sometimes on Twitter. works for Tor Books. He is sometimes on Twitter.