When I was a kid, I knew I belonged somewhere else. I couldn’t have told you exactly how I was different—only that I had nothing in common with the people around me, and they recognized it, and told me how strange I was in a thousand ways. At the time, I had no idea how common this was. I got my first computer when I left for college, was introduced to Usenet on my first day in the dorms. In the Before Time, there were no magic windows to learn how different life could be in another town, no place to read my classmates’ own doubts and insecurities, no magic to connect like-minded children across states or countries. Reality was my town, my school, my family—and the only doorways out were stories.

My favorite stories, then, were of people who found a way out of their worlds and into others—new worlds in which they could finally be themselves. My fondest wish was to get swept up by a tornado, trip over a portal, or convince a time-traveling away team to beam me up. Adventures may be dangerous, but they beat the hell out of loneliness. They’re worth it—anything would be worth it—to find out who you are and where you belong.

The other thing about adventures is that they end.

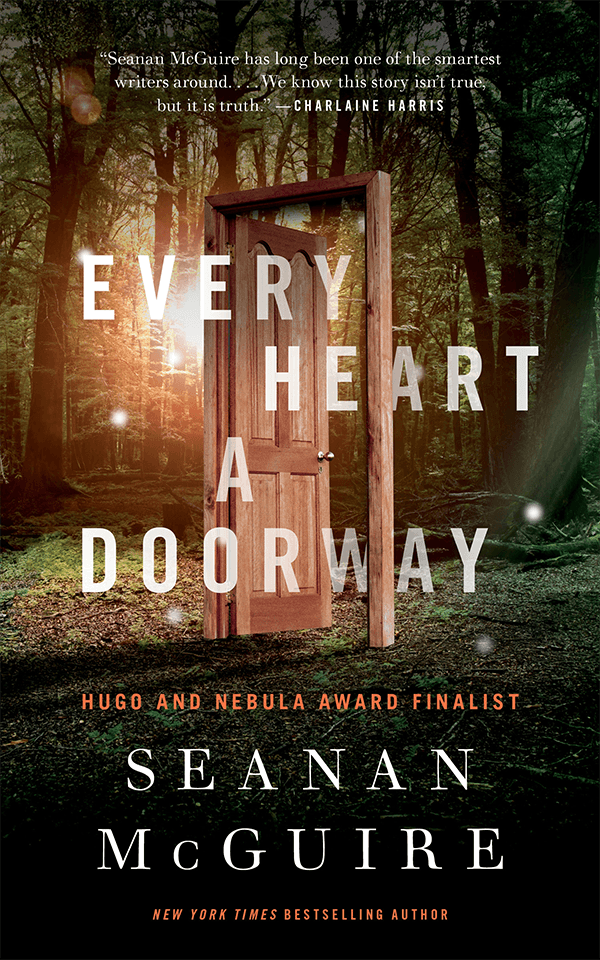

Seanan McGuire’s Wayward Children series is about what happens after the end of the adventure. What it’s like for naturalized citizens of Oz, Narnia, or Wonderland to be thrust back into a world they’ve outgrown, and families who can’t understand or even believe their experiences.

Before I go on, I have to introduce you to McGuire’s first take on these Girls Who Come Back, the glorious “Wicked Girls” anthem:

“Wicked Girls” is about the fury and power of women building their own stories, making them continue by sheer force of will. Wayward Children, by contrast, is about Dorothy and Alice and Wendy and Jane coming together and learning from each other’s experiences, helping each other heal, cheering each other on as they look for their doors home.

In celebration of the upcoming January 8th launch of In an Absent Dream, I’ll spend the next couple of weeks on a mini-reread of the Wayward Children series. We’ll explore all the directions of the Compass, and all the things that force happily Lost children to tumble back into being found. If you’ve already read the books, I invite you to reread along with me—there are secrets here that only reveal themselves through closer examination, like tiny doors woven by the queen of spiders. If you’re new to the Compass, I invite you to join us, and take a leap down that rabbit hole you’ve been waiting for.

Every Heart a Doorway introduces us to the doors, the worlds they lead to, and the principles that govern their openings and closings. Eleanor West’s Home for Wayward Children promises parents respite from the rare and terrible syndrome that some children develop in response to trauma—you know, the syndrome where they refuse to say anything about their kidnappers or their experience as a homeless runaway, and instead insist that they’ve spent the last several years in a world beyond human ken. The syndrome where they refuse to act like the innocent little kid you once loved, and thought you understood. The syndrome where they change.

In reality (such as it is), Eleanor is herself a returned child, and the school a safe haven where children who want desperately to go home can at least be together, and at least be assured that their experiences, and their changes, are real.

Nancy, once her parents’ “little rainbow,” ends up at the school after returning from the Underworld, where she joyfully served the Lord and Lady of the Dead in stillness and silence. Now she dresses in grayscale, and can stand still as a statue for hours on end and subsist on slivers of fruit. Naturally she’s assigned to a room with the always-moving, garishly-bright Sumi, who speaks in riddles and desperately misses her own home of nonsense and candy. She meets others with experiences superficially more like her own: twins Jack and Jill, who lived in a gothic land of vampires and mad scientists; and Christopher, who loved a skeleton girl. And Kade, a beautiful boy who once defeated a goblin prince, only to get kicked out of Fairyland for not being a girl. But something is wrong at the school, something that becomes obvious when they start finding the bodies of murdered students… starting with Sumi.

So where are we on the Compass this week?

Directions: Every Heart a Doorway focuses on Earth, a world that people leave from more often than travel to. We hear in passing about occasional travelers the other way, and eventually get hints that Earth isn’t the only from world. Returned travelers on Earth, as humans are wont to do, have tried to taxonomize their experiences. Worlds vary primarily along the main directions of the Compass: Nonsense versus Logic and Virtue versus Wicked. There are also minor directions like Rhyme, Linearity, Whimsy, and Wild. Kade suggests that Vitus and Mortis might also be minor directions.

Instructions: Earth is logical enough to have rules and nonsense enough to have exceptions. Doors show up for those who fit what’s behind them—but fits aren’t always perfect, and are more about what you need to grow than about making you perfectly happy. (There’s another school, for people who don’t want to return and who want to forget what was behind their doors.) Some doors open many times, some only once. And even if your door opens, it may close again if you take the time to pack.

Tribulations: The most dangerous things on Earth, for the Wayward Children—maybe even more dangerous than the murderer living among them—are well-meaning family members who just want to heal their delusions.

College was my doorway. Between one day and the next, I found myself surrounded by kindred spirits, in a place where I made sense. There were adventures enough to let me learn who I was, and heartbreaks and dangers, and I felt like I’d come home. One of the many things I encountered there for the first time was comic books, and my gateway comic (so to speak) was the X-Men.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

Even more than portal fantasies, this kind of story became my favorite: the story about people with very different experiences, but one vital thing in common, coming together and making a family. So now, reading as an adult, the character I identify with the most in Every Heart a Doorway is Kade. Kade, whose portal realm allowed him to grow into himself—and into someone who no longer fit the world that once claimed him. Who doesn’t want to forget, but doesn’t want to return, either. Whose place isn’t any one world, but the school itself, a solid point where wildly different people share and heal, and grow ready either to return home or to face down those who deny their realities. I’m with Kade—I’d feel constrained by a life that was all rainbows and candy, or all vampires, but I’d be pretty happy sitting in an attic surrounded by obscurely organized books, helping visitors solve their problems and find the right clothes to suit their inner selves. (You may now picture me looking wryly around my converted attic bedroom in the Mysterious Manor House, wondering if I should take a break from writing blog posts long enough to redistribute the household laundry.)

Kade also illustrates one of my favorite things about Wayward Children: it takes something that all too many magical school stories keep metaphorical, and spills it out into the text. The X-Men, especially with early authors, made mutants a half-reasonable stand-in for minorities and queer people. Many of us do in fact defend a world that hates and fears us, but without the decided advantage of superpowers.

Kade is trans, but that isn’t one of the things that drew him to his fairyland. The fairies stole him away to be a princess. It’s his archenemy, the Goblin Prince, who grants him the gift of recognition as prince-in-waiting with his dying breath. The fairies kick him out for not following their rules about who serves them, and his parents send him to the school because they want their “daughter” back. He fits better there than anywhere else, but even under Eleanor’s protection he gets nasty comments from a couple of rainbow-world mean girls.

So gender and orientation interact with the things that draw people to their doorways, but they also exist in their own right. We’ll learn later that the Moors support any sort of romantic entanglement that leads to dramatic lightning strikes, regardless of the genders involved. Nancy is asexual (but not aromantic, a distinction it’s nice to see made explicitly), and that has no particular influence on her Underworld experiences—Hades and Persephone “spread their ardor throughout the palace,” and plenty of their followers found their example contagious, but no one cared that Nancy didn’t. Her parents, on the other hand, add “stands uncannily still” and “wants to dress in black and white” to the list of things they don’t understand about her that starts with “won’t go on dates.”

For me, Nancy’s underworld was the most thought-provoking part of this reread. She makes sense as a narrator—the descent into the underworld is, after all, the original template for portal fantasy—but on my first read I found her an uncomfortable companion. Stillness and silence, as traditional feminine virtues, can certainly be sources of strength, but a world that encouraged them was hard to see positively. More than that, though, was the way Nancy’s stillness allows her to subsist on the most minimal of meals. In fact, she’s uncomfortable eating the amount that ordinary humans need to be healthy.

Everything else about the way her parents treat her is their problem. If your kid goes into a goth phase, if their interests change, if they tell you they don’t want to date—you should believe them, and accept the personal reality that they’ve shared. On the other hand, if your kid tells you they don’t need to eat—you shouldn’t accept that! You should do everything you can to help them overcome their eating disorder! And you might have forgivable trouble disentangling the eating disorder from other major changes that show up around the same time.

On this read, I still find Nancy’s parents more forgivable than they would be if she ate 2000 calories a day. But I’m more intrigued by the way her world builds strengths in places most people only see weakness: in stillness, in silence, in endurance. Those strengths allow her to recognize as true friends those who can see her power, and to be cautious of those who underestimate her. And they’re critical to her role in fighting off the danger facing the school. The school itself embodies what I love about such places: the combination of many different strengths to make a greater whole. Nancy’s stillness complements Sumi’s constantly moving mouth and hands, and the story recognizes and respects both. You need rainbows and lightning strikes, fairies and vampires, wicked logic as well as virtuous nonsense, to make this kind of family complete.

Strength—real strength, based on your own choices—is the gift that Nancy’s underworld offers. And unlike many of her classmate’s worlds, it offers the chance to live there forever, with those choices. When her Lord tells her to come back when she’s sure, he’s giving her a chance to choose rather than tumble. That, it turns out, may be the rarest gift on the Compass.

People are told to “be sure” twice in Every Heart a Doorway: once as both instruction and gift from Nancy’s Lord, and once in Jack and Jill’s description of their own door. In Down Among the Sticks and Bones, we’ll learn what those words meant for them.

Spoiler policy: Comments open to spoilers for the first three books, but no spoilers for In an Absent Dream until after it comes out.

The Wayward Children series—Every Heart a Doorway, Down Among the Sticks and Bones, Beneath the Sugar Sky, and the forthcoming In an Absent Dream—is available from Tor.com Publishing

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.