In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Today, I’m going to do something a bit different, and look not just at a work of fiction, but at a specific edition of a book and its impact on the culture and on publishing. That book is the first official, authorized paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien. Sometimes, the right book comes along with the right message at the right time and ends up not only a literary classic, but a cultural phenomenon that ushers in a new age…

And when I talk about the book ushering in a new age, I’m not referring to the end of the Third and beginning of the Fourth Age of Middle-earth—I’m talking about the creation of a new mass market fictional genre. While often comingled with science fiction on the shelves, fantasy has become a genre unto itself. If you didn’t live through the shift, it’s hard to grasp how profound it was. Moreover, because of the wide appeal of fantasy books, the barriers around the previously insular world of science fiction and fantasy fandom began to crumble, as what was once the purview of “geeks and nerds” became mainstream entertainment. This column will look at how the book’s publishers, the author, the publishing industry, the culture, and the message all came together in a unique way that had a huge and lasting impact.

My brothers, father, and I were at a science fiction convention—sometime in the 1980s, I think it was. We all shared a single room to save money, and unfortunately, my father snored like a freight train chugging into a station. My youngest brother woke up early, and snuck out to the lobby to find some peace and quiet. When the rest of us got up for breakfast, I found him in the lobby talking to an older gentleman. He told me the man had bought breakfast for him and some other fans. The man put his hand out to shake mine, and introduced himself. “Ian Ballantine,” he said. I stammered something in reply, and he gave me a knowing look and a smile. He was used to meeting people who held him in awe. I think he found my brother’s company at breakfast refreshing because my brother did not know who he was. Ballantine excused himself, as he had a busy day ahead, and I asked my brother if he knew who he had just shared a meal with. He replied, “I think he had something to do with publishing The Lord of the Rings, because he was pleased when I told him it was my favorite book.” And I proceeded to tell my brother the story of the publishing of the paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings, and its impact.

About the Publishers

Ian Ballantine (1916-1995) and Betty Ballantine (born 1919) were among the publishers who founded Bantam Books in 1945, and then left that organization to found Ballantine Books in 1952, initially working from their apartment. Ballantine Books, a general publisher that devoted special attention to paperback science fiction books, played a large role in the post-World War II growth of the field of SF. In addition to reprints, they began publishing paperback originals, many edited by Frederik Pohl, which soon became staples of the genre. Authors published by Ballantine included Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, C. M. Kornbluth, Frederik Pohl, and Theodore Sturgeon. Evocative artwork by Richard Powers gave many of their books’ covers a distinctive house style. In 1965, they had a huge success with the authorized paperback publication of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Because the success of that trilogy created a new market for fantasy novels, they started the Ballantine Adult Fantasy line, edited by Lin Carter. The Ballantines left the company in 1974, shortly after it was acquired by Random House, and became freelance publishers. Because so much of their work was done as a team, the Ballantines were often recognized as a couple, including their joint 2008 induction into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

About the Author

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) was a professor at Oxford University who specialized in studying the roots of the English language. In his work he was exposed to ancient tales and legends, and was inspired to write fantasy stories whose themes harkened back to those ancient days. His crowning achievement was the creation of a fictional world set in an era that predated our current historical records, a world of magical powers with its own unique races and languages. The fictional stories set in that world include The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, as well as a posthumously published volume, The Silmarillion. Tolkien also produced extensive amounts of related material and notes on the history and languages of his fictional creation. He was a member of an informal club called the Inklings, which also included author C. S. Lewis, another major figure in the field of fantasy. While valuing the virtues and forms of bygone eras, his works were also indelibly marked by his military experience in World War I, and Tolkien did not shy away from portraying the darkness and destruction that war brings. He valued nature, simple decency, perseverance and honor, and disliked industrialism and other negative effects of modernization in general. His work also reflected the values of his Catholic faith. He was not always happy with his literary success, and was somewhat discomforted when his work was enthusiastically adopted by the counterculture of the 1960s.

The Age of Mass Market Paperback Books Begins

Less expensive books with paper or cardboard covers are not a new development. “Dime” novels were common in the late 19th Century, but soon gave way in popularity to magazines and other periodicals which were often printed on cheaper “pulp” paper. These were a common source of and outlet for genre fiction. In the 1930s, publishers began experimenting with “mass market” paperback editions of classic books and books that had previously published in hardcover. This format was widely used to provide books to U.S. troops during World War II. In the years after the war, the size of these books was standardized to fit into a back pocket, and thus gained the name “pocket books.” These books were often sold in the same way as periodicals, where the publishers, to ensure maximum exposure of their product, allowed vendors to return unsold books, or at least return stripped covers as proof they had been destroyed and not sold. In the decades that followed, paperback books became ubiquitous, and were found in a wide variety of locations, including newsstands, bus and train stations, drug stores, groceries, general stores, and department stores.

The rise of paperback books had a significant impact on the science fiction genre. In the days of the pulp magazines, the stories were of shorter length—primarily short stories, novelettes, and novellas. The paperback, however, lent itself to longer tales. There were early attempts to fill the books with collections of shorter works, or stitch together related short pieces into what was called the “fix-up” novel. Ace Books created what was called the “Ace Double,” two shorter works printed back to back, with each having its own separate cover. Science fiction authors began to write longer works to fit the larger volumes, and these works frequently had their original publication in paperback format. Paperbacks had the advantage of being less expensive to print, which made it possible to print books, like science fiction, that might have narrower appeal and were aimed at a particular audience. But it also made it easier for a book, if it became popular, to be affordable and widely circulated. This set the stage for the massive popularity of The Lord of the Rings.

A Cultural Phenomenon

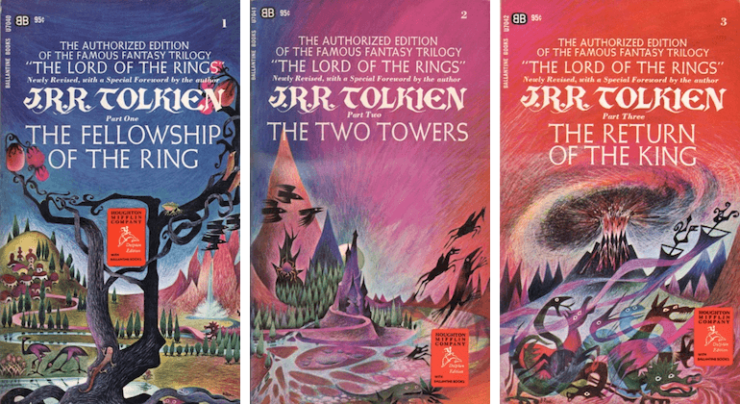

The Lord of the Rings was first published in three volumes in England in 1954 and 1955: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King. It was a modest success in England, and was published in a U.S. hardcover edition by Houghton Mifflin. Trying to capitalize on what they saw as a loophole in copyright law, Ace Books attempted to publish a 1965 paperback edition without paying royalties to the author. When fans were informed, this move blew up spectacularly, and Ace was forced to withdraw their edition. Later that year, the paperback “Authorized Edition” was released by Ballantine Books. Its sales grew, and within a year, it had reached the top of The New York Times Paperback Best Seller list. The paperback format allowed these books a wide distribution, and not only were the books widely read, they became a cultural phenomenon unto themselves. A poster based on the paperback cover of The Fellowship of the Ring became ubiquitous in college dorm rooms around the nation. For some reason, this quasi-medieval tale of an epic fantasy quest captured the imagination of the nation, particularly among young people.

It’s hard to establish a single reason why a book as unique and different as The Lord of the Rings, with its deliberately archaic tone, became so popular, but the 1960s were a time of great change and turmoil in the United States. The country was engaged in a long, divisive, and inconclusive war in Vietnam. In the midst of both peaceful protests and riots, the racial discrimination that had continued for a century after the Civil War became illegal upon passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Gender roles and women’s rights were being questioned by the movement that has been referred to as Second Wave Feminism. Because of upheaval in the Christian faith, many scholars consider the era to be the fourth Great Awakening in American history. Additionally, there was also wider exploration of other faiths and philosophies, and widespread questioning of spiritual doctrines. A loose movement that became known as “hippies” or the “counterculture” turned its back on traditional norms, and explored alternative lifestyles, communal living, and sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Each of these trends was significant, and together, their impact on American society was enormous.

The Lord of the Rings

At this point in my columns, I usually recap the book being reviewed, but I’m going to assume that everyone reading this article has either read the books or seen the movies (or both). So instead of the usual recap, I’m going to talk about the overall themes of the book, why I think it was so successful, and how it caught the imagination of so many people.

The Lord of the Rings is, at its heart, a paean to simpler times, when life was more pastoral. The Shire of the book’s opening is a bucolic paradise; and when it is despoiled by power-hungry aggressors it’s eventually restored by the returning heroes. The elves are portrayed as living in harmony with nature within their forest abodes, and even the dwarves are in harmony with their mountains and caves. In the decades after the book was published, this vision appealed to those who wanted to return to the land, and who were troubled by the drawbacks and complications associated with modern progress and technology. It harkened back to legends and tales of magic and mystery, which stood in stark contrast with the modern world.

The book, while it portrays a war, is deeply anti-war, which appealed to the people of a nation growing sick of our continued intervention in Vietnam, which showed no sign of ending, nor any meaningful progress. The true heroes of this war were not the dashing knights—they were ordinary hobbits, pressed into service by duty and the desire to do the right thing, slogging doggedly through a despoiled landscape. This exalting of the common man was deeply appealing to American sensibilities.

The book, without being explicitly religious, was deeply infused with a sense of morality. Compared to a real world filled with moral grey areas and ethical compromises, it gave the readers a chance to feel certain about the rightness of a cause. The characters did not succeed by compromising or bending their principles; they succeeded when they stayed true to their values and pursued an honorable course.

While the book has few female characters, those few were more than you would find in many adventure books of the time, and they play major roles. Galadriel is one of the great leaders of Middle-earth, and the courageous shieldmaiden Éowyn plays a significant role on the battlefield precisely because she is not a man.

And finally, the book gives readers a chance to forget the troubles of the real world and immerse themselves completely in another reality, experiencing a world of adventure on a grand scale. The sheer size of the book transports the reader to another, fully-realized world and keeps them there over the course of huge battles and long journeys until the quest is finally finished—something a shorter story could not have done. The word “epic” is overused today, but it truly fits Tolkien’s tale.

The Impact of The Lord of the Rings on the Science Fiction and Fantasy Genres

When I was first starting to buy books in the early 1960s, before the publication of The Lord of the Rings, there was not much science fiction on the racks, and fantasy books were rarely to be found. Mainstream fiction, romances, crime, mystery, and even Westerns were much more common.

Buy the Book

The Ruin of Kings

After the publication of The Lord of the Rings, publishers combed their archives for works that might match the success of Tolkien’s work—anything they could find with swordplay or magic involved. One reprint series that became successful was the adventures of Conan the Barbarian, written by Robert E. Howard. And of course, contemporary authors created new works in the vein of Tolkien’s epic fantasy; one of these was a trilogy by Terry Brooks that began with The Sword of Shannara. And this was far from the only such book; the shelf space occupied by the fantasy genre began to grow. Instead of being read by a small community of established fans, The Lord of the Rings became one of those books that everyone was reading—or at least everyone knew someone else who was reading it. Fantasy fiction, especially epic fantasy, once an afterthought in publishing, became a new facet of popular culture. And, rather than suffering as the fantasy genre expanded its borders, the science fiction genre grew as well, as the success of the two genres seemed to reinforce each other.

One rather mixed aspect of the legacy of The Lord of the Rings is the practice of publishing fantasy narratives as trilogies and other multi-volume sets of books, resulting in books in a series where the story does not resolve at the end of each volume. There is a lean economy to older, shorter tales that many fans miss. With books being issued long before the end of the series is completed, fans often have to endure long waits to see the final, satisfying end of a narrative. But as long as it keeps readers coming back, I see no sign that this practice will be ending any time soon.

Final Thoughts

The huge success and broad appeal of The Lord of the Rings in its paperback edition ushered in a new era in the publishing industry, and put fantasy books on the shelves of stores across the nation. Within a few more decades, the fantasy genre had become an integral part of mainstream culture, no longer confined to a small niche of devoted fans. Readers today might have trouble imagining a time when you couldn’t even find epic fantasy in book form, but that was indeed the situation during my youth.

And now I’d like to hear from you. What are your thoughts on The Lord of the Rings, and its impact on the fantasy and science fiction genres?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

Professor Tolkien’s book was one of the first fantasy novels to impress me with its thematic depth and I was happy to discover The Hobbit and The Silmarillion later on: I will always have time for quality Tolkien commentary. I am inclined to be more ambivalent than our host about its influence on epic fantasy: while so many great writers have engaged with and built on Tolkien’s work, a larger number have parasitized it, trading weighty issues for mere volume. I now seldom read contemporary examples of the genre. I think that when money got into epic fantasy, a lot of the magic went out of it.

Anyway, a shot of nostalgia courtesy Pauline Baynes:

ETA: Because I forgot to mention it, happy 127th birthday, J. R. R. Tolkien!

Reading The Hobbit and then immediately LOTR when they were first recommended to me (age 13, maybe?) I was bored by the Appendices and avoided the poetry. For instance, I was disgusted at how “derivative” the song is that Frodo sings at the Prancing Pony. And yet, I wanted to hear melodies for the songs and began picking out some myself, which might explain why I was disappointed by the ones by Donald Swann. Then, in high school and college, I found only one other person who loved the books and for a while we wrote back and forth to each other by transliterating English into the tengwar. In the early 70s, we were champing at the bit, knowing The Silmarillion existed but wanting it now. But soon after, I abandoned Tolkien for “the real world” and didn’t come back to it until the first Peter Jackson film was released. Then, when I picked up the books again, I was surprised and delighted and captivated in a way I didn’t expect. As with many rereadings, because I already knew the plot, suddenly I was appreciating the language and the characters and settings. Now I dug into the Appendices and enjoyed the poetry.

Sorry, that was OT, but I just had to share my “history” with LOTR. At about the same time as I abandoned Tolkien I also quit reading SciFi entirely, so I pretty much missed the shift, or only experienced the very beginnings of it. Coming back so recently, I have a lot to catch up on . . . impossible!

Hi Alan

A very nice overview. I remain a big fan of LOTR, (the books) and The Hobbit. We have seen lots of editions and images including Tolkien’s own drawings but after reading your post I also remembered how iconic the Barbara Remington covers were for me at the time. I also loved the cover she did for The Worm Ouroboros by Eddison, another fat multi-volume set. I just loved the world building in LOTR, the songs, myths and appendices that created such a rich environment I have reentered it many times over the years. Your observation that “While There is a lean economy to older, shorter tales that many fans miss.” does capture my problem with the genre at present, the success of LOTR and paperback publishing in general has spawned huge fantasy and science fiction series that I often find do not hold my interest, or discourage me from even starting. I often think that a more direct, less embellished approach to setting and plot would result in a more satisfying read.

But none of this holds for LOTR, there I am perfectly happy to stroll around the Shire, or visit Tom Bombadil or listen to the elves singing in Rivendell.

Happy Reading

Guy

A few years ago, Andrew Liptak wrote a nice article at Kirkus about how the Ace edition influenced the publishing and popularity of LOTR.

I was in my early teens when LOTR came out, and I remember the hoopla about the pirate version as well as the authorized one. My oldest brother read it first. I read it a few years later and agreed with my brother that it was so dang immersive. I’d put it down and blink a lot to reorient myself into the real world because Tolkien’s world became the real world when I was reading it. The books weren’t quite the phenomena that the Harry Potter books were, they weren’t as mainstream, but they were a phenomena, nevertheless. LOTR would have been a phenomena whatever was happening in the real world.

A bit of a correction. With the exception of Harlequin which is a genre unto itself, the romance industry didn’t really exist until the mid-Seventies with the publication of Kathleen Woodiwiss’ first historical romances.

@@.-@ I wasn’t aware of Mr. Liptak’s quite excellent article when I wrote this. He goes into a lot more detail on the publishing issues than I did, so I would recommend that anyone who wants to learn more click on the link you provided.

@5 That’s interesting info about romances. My mom read scads of paperback gothic and historical romances before the 1970s–I wonder how they were categorized on the shelves if romance was not yet considered a genre–general fiction I suppose. From the Wikipedia article on romantic fiction, it looks like the advent of mass market paperback originals had as profound an effect on romances as it did on science fiction.

@1 We don’t get covers like that much anymore. Usually they are just a black or half-lit background, either a shirtless guy, or a scantily clad woman half turned away from the reader, and scowling. Cover art right now is so damn generic. Bring back the epic paintings, bring back colourful covers.

Come to that, bring back books about wood elves, and people going on a quest. No twists, no “playing with the genre”, none of that gimmicky stuff, just good old fashioned fun.

@@@@@ 6 Before the mid-Seventies, what we now classify as romance didn’t have its own shelves in bookstores, or publishing lines. Gothics weren’t called Gothic romances, they were Gothic novels or Gothic historicals, and they were shoved in with the historical novels or on the general shelves of what we now called the mainstream books. When Woodiwiss and her sisters in historical romance began to sell zillions of books and the publishers and bookstores realized what a gold mine they had, romance became a genre with publishing lines and bookshelves devoted to them.

Alan, I agree with your narrative of the effect of LOTR on readers, SFF genre, and on publishing practices. I first read LOTR when I was a college student in the early 1970s. I had an interest in fantasy and in medieval / renaissance / early modern English and European history in the late 1960s, largely initiated by reading T.H. White’s Arthurian romance version “The Once and Future King” (publication date 1958) and by reading and attending several Shakespeare plays. I was also a science geek, but wasn’t particularly interested in science fiction in the late 1960s – early 1970s. In college I concentrated in chemistry, English and European history, and English classes, including the standard Beowulf – Chaucer – Shakespeare English 101-102 sequence, and a “History of the English Language” 300-level course – before I first read LOTR. I discovered SF, including “literary” SF, only later, in the late 1970s.

I’m from a younger generation than those who read LOTR when it was first published, so my knowledge of older fantasy is patchy at best, but I’m not sure how much LOTR is to blame for never-ending epic fantasy trilogies and series, at least not as a direct structural template. Certainly LOTR started the whole secondary world thing defined as being distinct and inaccessible from our everyday world, and for sure books following in its wake have multiple stories/books are set in the same world, but these, in my admittedly limited experience, tend to be more episodic than series are today. Taking the first Shannara “trilogy” as an example, all three books follow different characters on different stories/arcs. The first one, The Sword of Shannara, is basically the entire story of LOTR but shorter. LOTR was planned as a single story and therefore had no resolution within each volume, only advancing stages, whereas modern 14 book long series usually have some conflicts resolved in each volume while leaving other conflicts open for future development. To me, the original Shannara trilogy is much more like the duology of The Silmarillion and LOTR as Tolkien intended but never got to complete in that each book in the series follows a distinct set of characters and conflict (theoretically in the case of the uncompleted Silmarillion) and not so much like the LOTR “trilogy”. The current epic fantasy trend of series with both a intra-book arc and an inter-book arc is much more Robert Jordan’s fault than Tolkien’s (well, I say “fault”).

Come to that, bring back books about wood elves, and people going on a quest. No twists, no “playing with the genre”, none of that gimmicky stuff, just good old fashioned fun.

You think Tolkien doesn’t have that? He’s coming off a tradition of heroic romance that is literally millennia long, and writing his own take on it, and who does he have as heroes? Not the ancient and beautiful Elves, not the learned Wizard, not the bold warrior king (or the farm boy who grows up to find he’s a lost prince); he invents a race of small round indolent people with hairy feet, and he makes the entire survival of Good against Evil dependent on them. His entire work is a twist on the genre.

I’ve wondered about the 12 year gap between LOTR and Shannara; did nobody else significantly cash in on the template before Terry Brooks? (Stephen R. Donaldson also debuted that year, I think). Checking Wikipedia I see that Brooks started writing it in 1967, but I’m still astonished it took that long for anyone to cash in; today you’d see copy-cats of anything that successful within a year. Lester del Rey offered a clue. Working under the Ballantines, he viewed Shannara as “the first long epic fantasy adventure which had any chance of meeting the demands of Tolkien readers for similar pleasures.” But still, nobody jumped on faster? That’s incredible.

I find it interesting that Mervyn Peake predated Tolkien’s work by almost two decades, also wrote large and fantastical, but didn’t make the same splash. Although he could have been inspired by the Hobbit; and his work doesn’t have the same depth and breadth.

The Sword of Shannara was sold with the blurb, “For someone who has been looking for something to read since he finished The Lord of the Rings.”

I read the book and snarled, “By someone who was looking for something to write since he read The Lord of the Rings.”

I never read another thing Brooks wrote.

@13 To be fair to Brooks, the following books are much less of a straight copy. I think I read somewhere Brooks was told that Sword had to be as LOTR as possible and it’s not until Wishsong that he could write his own thing. Not that I’m entirely sure it’s worth diving into Brooks’ series this late in the game.

I’m not sure the details of American society in the 1960s were terribly important to the books success. After all, the popularity of Lord of the Rings goes far beyond the boundaries of:

a) The United States of America,

b) The 1960s.

You should only worry about the effects of American society when thinking about something the success of which is limited to America. If something is popular across the world, you should think about things that are true about people everywhere.

Tolkein lived down our road when I was a child, of course we had The Hobbit read to us, and then graduated to The Lord of the Rings when we were old enough to read it for ourselves, in my case when I was eight.

@15 My question was not why The Lord of the Rings was popular around the world (which it was), but why it became so popular in the USA, which is why I focused on what was going on in the USA when the book was released there in paperback, and became a best seller. I think that decade was a unique period where many new things became popular, or new trends started; things that might not have happened at a different time. People in the USA are not always willing to embrace books from other countries, no matter how popular they are elsewhere. The worldwide popularity of the book would have been a much larger thesis than the one I chose to embrace.

@16 Cool! I used to read The Hobbit to my younger brothers when I came home from college for visits, but both of them got impatient, and finished it themselves during one of my longer absences.

I refuse to read a series until it is complete. I just don’t have the memory capacity to hold all that until the next volume appears in two years. I’m currently waiting on the last volume of James S. A. Corey’s Expanse series before I start on it. But that hasn’t prevented me from watching the SyFy series. Similarly with Game of Thrones. In fact, I suspect that Martin will never finish the story. So the HBO series will be all the closure we get.

I am the generation that embraced the paperbacks. I had this poster on my wall from the age of 12 all through high school, and I read my copies of the Ballantine edition until they literally fell apart.

I even remember noticing, quite distinctly, when the word “fantasy” first started appearing on the spines of paperbacks in the science fiction sections of the used bookstores I haunted.

This piece includes a lot of publishing history I didn’t know or had forgotten, and thanks for that. It is also a perfect recap of my memory of those years in my imaginative life. Except for one experience, that I suspect many of us who are old enough may have shared.

Back then, in the late 60s through the 70s, my peers and most adults thought I was really weird (even seriously eccentric, crazy cat lady, mentally defective weird) for loving Tolkien so passionately, along with Star Trek, Star Wars and all the other major SF/F worlds of that decade. The flip side of the ostracism was that I found my true friends in my fellow oddballs. It still hurt though, until I learned not to care for those opinions.

So now of course, I savor the knowledge that my young literary tastes were in fact very advanced. First we had the huge vindication in 2000 of seeing The Lord of the Rings included in _all_ of the “Most Important Books of the 20th Century” lists, usually in the top 3. The next year, Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring came out – and suddenly everyone knew what a hobbit is. The rest of the world finally caught up to us fantasy nerds.

I read the Ballantine editions in ’66 or ’67 but what stands out for me from a publishing standpoint was that Adult Fantasy series. I’m pretty sure I read every single book in the series, or damn close, and was introduced to writers like James Branch Cabell, Lord Dunsany and Clark Ashton Smith. (I was surprised to note that the series did not include the Ballantine editions of The Worm Ouroroboros or the Gormenghast trilogy.) There was an explosion of paperbacks at the time, featuring Conan and Tarzan and masses of good, bad and indifferent sword & sorcery, but much of the real quality fantasy was published in that Ballantine series. As a writer, Lin Carter was, uh, not exciting but he was a hell of a good editor.

Two comments:

Ian Ballantine was also Penguin America during the war. See http://nyapril1946.blogspot.com/2012/03/paperback-entrepreneur-ian-ballantine.html . Amusingly all three companies – Penguin, Bantam, Ballantine are now all part Penguin Random (or as some like to call it Random Penguin).

“In the 1930s, publishers began experimenting with “mass market” paperback editions of classic books and books that had previously published in hardcover. This format was widely used to provide books to U.S. troops during World War II. In the years after the war, the size of these books was standardized to fit into a back pocket, and thus gained the name “pocket books.” “

The first American company to make paperback books popular was Pocket Books in 1939. The books the US troops had during the war – Armed Services Editions – were designed in a smaller trim size and bound on the short side to easily fit their pockets. There’s a good Wiki on the Armed Services Editions and this from the Library of Congress: https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2015/09/books-in-action-the-armed-services-editions/?loclr=ealocb

LOTR was never inteded as a triology by Tolkien. He wrote it as one long continuing story. When LOTR was first published in Britain, the publisher split it in 3 books because paper was still scarce and expensive after the war, and he thought people might refrain from buying a very big, expensive book. Also, the publisher expected to get reviews for three books instead of one. Later, most other publishers aparently did the same, but I’m happy that I managed to get a one-volume paperback edition when I was on holiday in Wales some 25 years ago.

Thanks for this. I enjoyed it. There is a book, Architect of Middle Earth, which I found very interesting, particularly the chapter on how LOTR first got published as “works of genius” that were not expected to make a profit.

I found LOTR on a library display case when I was about 12 and had read every “kids” book my small town library carried. (I actually picked up Two Towers first so I knew the whole time that Boromir was going to die.) It absolutely captivated my imagination, influenced who I am today and made me a lifelong fan of fantasy. I used to get the LOTR artist’s calendars for Christmas. I still have them along with the book set I got in the 70’s. I am eternally grateful to Tolkien, and I suppose Ballentine too, for creating the fantasy genre I so enjoy. I will say that the one thing about his books that stand out and I think are a big reason for his mainstream appeal is the beauty of his writing and his ability to create the scene, but let us imagine (or not) the violence. I’m old, I know, but I find so much modern fantasy too graphic. I know war, rape, torture etc is horrible. I don’t need every detail described.

Those three paperbacks were my first introduction to Tolkien’s writing (I actually read them before I read The Hobbit) and they introduced me to a lifelong love with everything to do with Middle Earth. While those three books are long gone, I currently have multiple copies of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, alone with a complete collection of all the other books containing his work published posthumously by his son.

I also had a poster of that cover art hanging on my bedroom was until I got married.

“A poster based on the paperback cover of The Fellowship of the Ring became ubiquitous in college dorm rooms around the nation.” The poster than I had in college (late 70’s) was actually made up of all three of the covers, which make a continuous picture. I still have that poster and consider that edition to be the “best”.

I don’t quite remember when LOTR came out (being slightly too young) but loved it when I did finally read it. I found the first 100 pages or so of Fellowship to be extremely slow, but I pushed through them and loved the rest. Years later when I read the books out loud to my children, I insisted that they couldn’t veto the book until after the first 100 pages.

I was a freshman in college in 1966, whne someone introduced me to “The Hobbit” during finals (no; it wasn’t “quite” a mistake!). Finished it quickly, and asked him if he had any more like that. He lent me LOTR. Luckily I has a couple days until my next final, so I literlally read all three in about a day and a half, taking time out to eat. I just could not put them down.

Later on, I ran into a few people who eventually became lifelong friends, and was introduced to “Gormenghast” (weird and far better than the miniseries on teevee a few years ago), and ER Edison’s stuff. I enjoyed them all, but LOTR is, I guess, the defining set of fantasy books for me. In the ’70’s I tried “the “Silmarillion” and couldn’t get through it.

Way back in seventh grade, a friend and I debated the best trilogy. I put up the Foundation Series, he put up LOTR. He won…

I enjoyed it so much, that I ‘borrowed’ my sister’s copies. You can see their covers above! Unfortunately, while I have FotR and RotK, I never got to borrow TT! I used to read them every year at Christmastime.

During one of those rereads, I was at work, and my boss walked by. He stopped, came back, took one look at the edition of RotK I was reading, and was aghast that I was actually reading a FIRST EDITION!!!!

So, I bought a new all in one edition to read from then on. Loaned it to a friend, and now have a third copy I finished last week…

One of the advantages of getting old is that you experience history before it’s rewritten:

“Ace Books attempted to publish a 1965 paperback edition without paying royalties to the author. When fans were informed, this move blew up spectacularly, and Ace was forced to withdraw their edition.”

Obviously, Ace Books didn’t “attempt” to publish the trilogy, they did publish it, and with great success. They withdrew their edition only in the sense that they did not send it back for another printing after it sold out. Nor were they “forced” to do it: I well remember the note from Tolkien on the covers of the early Ballantine editions, begging readers to buy those editions and not any others. If Ballantine and Tolkien had the law on their side, they would not have had to do that.

Donald Wollheim’s audacious decision to publish the trilogy in paperback, with dynamic covers by the great Jack Gaughan (who had actually read the books, unlike the Ballantine artist, apparently) is what made the books a cultural phenomenon. Thinking back, the way I figure it is, Ace Books must have been making so much money that the publishers let Wollheim run wild with what they considered a crackpot scheme, a project that violated every rule of paperback publishing at the time, pushing the technology to the limit, and in a genre for which “everybody knew” there was little demand. You might compare it to Walt Disney’s backers acquiescing to his absurd notion of building an amusement park.

One thing that struck me at the time was the contrast between the Gaughan covers, which brought to life exciting scenes from the books, and the boring landscapes of the authorized editions. Now, as the Liptak article referenced above explains, without the Ace edition there would have been no paperbacks at all, and Tolkien would be about as well known as John Collier or Mervyn Peake. I wonder, though, if the “boring landscape” editions had been the first and only paperbacks, would the trilogy still have been a hit? Would we still be talking about it?

It’s no great mystery why 60s counterculture embraced Tolkien. To paraphrase some wag (I don’t recall whom), the protagonists smoke weed, eat mushrooms, then head out to meet the talking trees. …The very narrative structure of LOTR recalls the rhythms of an intense mushroom trip, oscillating between phantasmagorical horrors and ecstasies: Weathertop/ Rivendell/ Moria/ Lothlorien/and so on.

While I presume the resemblance is an innocent coincidence, Tolkien’s own drugs of choice having been mere tobacco and beer, who knows? Maybe he was subconsciously tapping into the zeitgeist of the decades to come. If that’s the case, what a delicious irony that the universe chose a middle aged conservative Christian as one of the foremost prophets of 60s psychedelia.

Let us not forget the majesty that is the Ballad of Bilbo Baggins…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0onCSWLkB8

Spock, singing about hobbits? What’s not to love!

LOTR were the first books I ever bought with my own money. I was a sophomore in high school – I remember the large brown padded envelope showing up on a Thursday afternoon, and the smell of the ink rising from the pages. I read through the night, played hooky from school for the first and only time in my life the next day, and after I finished all three books, started over again. I played the Moody Blues in repeat the entire time. Even now, almost fifty years later, I hear the Moody Blues, and I am instantly transported back to the shire.

Reading those books was the most visceral experience I’ve ever had.

When the Tolkien books came out, it wasn’t anything my New England parents would allow in the house. It took going to my father’s sister for a visit for me to learn about fantasy. My tutor? Those three book covers, which my cousin had carefully replicated and hung in my aunt’s guest room were just amazing. Over the years I saw them as the doorway into SciFi and Fantasy, and lovingly took those books cross country in my working life until they were donated last spring in a 60% downsizing.

I still want nothing to do with the Peter Jackson movies, especially when my once pastor preached the *movie* story of ROTK, and then got defensive when I “called” him on it [turns out he’d never read the books]….

It was the Ballantine edition of Lord of the Rings and the UK edition of Frank Herbert’s The Dragon Under the Sea that hooked me on SF & F. That genre did not feature at all in my local library (apart from Shute’s On the Beach) – this being a small branch library in a seaside town in southern England (funnily enough, the same town Tolkien retired to).

I came across LotR after my parents split up when my mother was clearing out boxes of my father’s books from the attic. In amongst the Sven Hassells and similar, I came across this odd-looking book – intrigued, I began reading it and got sucked in. I guess he’d found it in a rack either at an airport bookstall or hotel lobby on a business trip in the Middle East and probably only got it because he’d already read everything else.

I never managed to get all 3 of the BB paperbacks – my Dad’s original LoTR fell apart (with a broken binding), I found a copy of TTT, replaced LoTR, and never came across TRotK. I now have a nice box set instead.

Has everyone forgotten Michael Moorcock and his books and the epic sagas of Elric and Dorian Hawkmoon? Those were late 60s phenoms of the offshoot S&S but still grand absorbing stories w/multi book series.

“The true heroes of this war were not the dashing knights—they were ordinary hobbits, pressed into service by duty and the desire to do the right thing, slogging doggedly through a despoiled landscape.”

If you want to understand where the hobbits came from, see Peter Jackson’s documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old. You will see the faces, and hear the voices, of the common young men from all over England, whose courage and good humor so impressed the young Lieutenant Tolkien as they held the line against barbarism.

Wow. Revisionist history. Another in a long history of people making statements about Donald A. Wollheim and the publishing of the original US paperback edition of LoTR that is at odds with what rally happened.

I knew Don at the time, and the blame for the original publication of LoTR can be laid at the door of Houghton Mifflin, which got greedy and violated the copyright terms then extant, placing the book into public domain in the USA.

The fans had nothing to do with “When fans were informed, this move blew up spectacularly, and Ace was forced to withdraw their edition.” If the author believes at the publisher of Ace Books, A.A. Wyn, and his editor, Donald A. Wollheim, would be forced to withdraw a book because of the supposed outrage by a very small but very vocal subset of total readers, I have a bridge to sell him.

Until I read this I did not realize that I read these editions of LOTR within a year of the American publication. I assumed then they’d been around a while. Since then I’ve re-read LOTR about once a decade.

Yes, Brooks and Jordan are pale imitations, but can you blame them (or their publishers)?

Thank you for this article! It seems that I am doomed to not get to experience some of my favorite things in real time. The first big ‘geeky’ loves of my life were the Beatles (maybe not really a ‘geeky’ thing, but my level of obsession with them was, especially growing up in the 80s/90s), Lord of the Rings and Star Wars, all things which pre-date me (born in 82, ha). But I guess I did get to ride the Harry Potter/Wheel of Time wave ;) And I feel like Weird Al is finally now getting the mainstream respect he deserves so I guess I have the right to be all hipster-y about that ;)

Regarding Lord of the Rings – honestly, it is probably what actually pulled me into hard core nerddom. When I was in sixth grade, one of my aunts passed away (quite tragically) and during the funeral I was a bit out of place, and one of my uncles was talking to me about the Lord of the Rings since he knew I loved to read. That Christmas he sent me the Hobbit and Fellowship.

I enjoyed them, although I know I missed a lot. I re-read them in 8th grade, taking my time, and was really blown away. At that time it was still kind of a weird thing to be into it – I had one friend who was also really into them and we used to try to answer insane trivia questions with each other. Somebody recommended the Silmarillion to me and it was a bit tricky to find. Of course, now, thanks to Peter Jackson, (whatever my complaints with the movies) we actually see people go on late night TV bragging about reading it, lol.

Speaking of subverting tropes, I think what is also notable is that, technically, his hero FAILS. At least, on his own power. He doesn’t return to the Shire triumphant and able to enjoy the fruits of his labor. He’s wounded and in need of healing for the rest of his days. Which, as mentioned, really is an anti-war story, and also one of great sacrifice. The story is about hope and perseverence, but always a thin strand of it, on the knife edge of despair. I really didn’t understand this until I was an adult.

@32 – your story makes me chuckle as it almost sounds like your pastor is no longer your pastor due to his oversight. But ah, that means his only knowledge of Faramir is that he’s some guy who tried to take the Ring from Frodo. I recently introduced my young kids to the movies – we didn’t have time to read the books before a trip to New Zealand – but when we got to that part, I stopped the movie for the night. I read to them a few chapters from the book, and then the next night I conveniently started the movie in the next scene. So as far as they know…Faramir never tried to take the Ring. Ever. :)