After reading and rereading so many Golden Age Norton space adventures, shifting to the Magic books feels like starting all over again with a new author. We’re in a completely different genre, children’s fantasy, and a completely different universe, revolving around kids and controlled by magic. Even the prose feels different: clearer, simpler, with fewer archaisms and stylistic contortions.

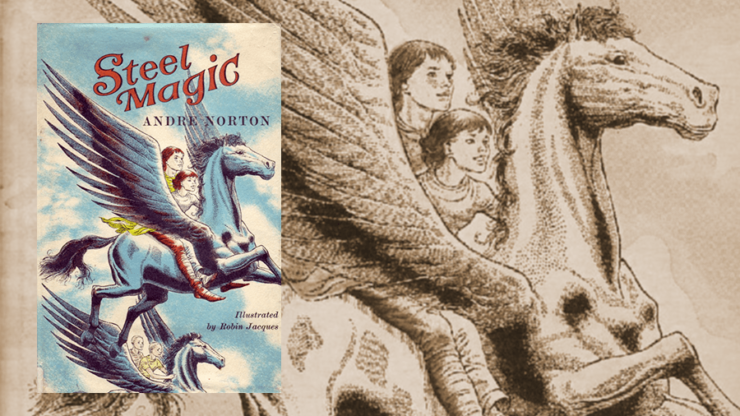

Steel Magic was the first of the series to be published, in 1965. It came in the midst of an efflorescence of kids’ fantasy, including A Wrinkle in Time (1962), and it built itself around cherished themes in the genre: magic, portals, groups of free-range siblings saving enchanted worlds.

Magic and portals were very much on Norton’s mind at the time—she was also writing and publishing the early Witch World books—but the genre would have been both dear and familiar to her. She mentions one other book in the novel, The Midnight Folk, which I hadn’t known at all. It turns out to be a 1927 novel by John Masefield—yes, that John Masefield, poet and Poet Laureate, whose “Sea Fever” was a staple of my school textbooks. He wrote prose for adults and children, as well. I had no idea.

For my personal literary canon, the closest analogue to Steel Magic would be C.S. Lewis’ Narnia books. Here as there, two brothers and a younger, innocent, traditionally girly sister (no Susan here; poor Susan, erased at the start) are dumped on an uncle while their parents are away on military business. The uncle lives in a mysterious mansion surrounded by equally mysterious grounds, and of course they go exploring and find a portal to a magical world.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

The world they’re called into has close ties to our own, so much so that the evil of that world bleeds over into ours. Merlin the Enchanter tried to find another mortal to help fight the evil with the power of cold iron, but failed and had to return. It’s his mirror that serves as the portal.

Meanwhile he, King Arthur, and Huon of the Horn, all formerly mortal, have been robbed of their magical talismans: a sword, a horn, a ring. Greg, Eric, and Sara are brought through the portal by some incalculable power to recover the talismans and save both worlds.

Norton adds a few twists to the template. The kids’ magical talismans come to them by literal chance, when Sara wins a picnic basket at the Strawberry Festival in town. It’s a very modern basket, with plastic plates and cups, but the cutlery is steel, which is made of cold iron and is therefore poisonous to magical creatures. On their separate quests, each child chooses or is chosen by a utensil which magically transforms into a weapon.

To add to the challenges, the children have individual fears and phobias: the dark, water, and spiders. Each quest requires the child to face his or her fear and conquer it in order to win the talisman. Sara’s quest has an added complication, that a human can’t enter the place where Merlin’s ring is hidden. She has to do so in the form of a cat. (The ring she’s seeking, be it noted, has the power to transform a human into various animals.)

I’m not a fan of plot-coupon or grocery-list quest fantasy, and Steel Magic is solidly anchored in the genre. The quests are mechanically constructed; each kid has a similar adventure, runs into similar problems, and uses his or her weapon similarly, then loses it. The magical items get checked off the list, and the items’ owners are waiting passively to claim them, strongly (but not too strongly) obstructed by the bad guys.

The battle to save both worlds happens offstage. The kids have done their jobs, they get a round of thanks—but wait! They can’t go home! They left their magical items behind!

No problem, says Merlin. Zip, zap, there they are. Bye, kids, thanks again, don’t worry about us, have a nice mundane life.

And that’s that. As a tween I wouldn’t have had a lot of problems with this kind of plotting. It’s comforting to know that whatever terrors you may fall into on the other side of Merlin’s mirror, you can always go back to where you were before.

As an adult who remembers the picnic set and the presence of Merlin but nothing else, I wish there were more to this than ticking boxes and balancing separate characters in separate chapters. They don’t even get to be part of the great battle it’s all supposed to lead up to. They get patted on the head and sent off to bed, and then the adults take over.

It’s a little too kid-safe. Scary, but not too scary. Dangerous, but not too dangerous. Nothing really bad happens. At least the cutlery isn’t plastic, too.

The point of kids’ fantasy is that the adults have made a giant mess and the kids will save everything, and they won’t do it easily and they won’t always be safe, either. The Pevensies do it in the Narnia books, and Dorothy does it in Oz—there are Oz echoes here, what with the picnic basket and the wicked witch. Things get put back where they were, yes, but the kids don’t get sent home before the big battle. They star in it. For them, the stakes are real. They have far more to lose than their chance to go home.

I looked a bit askance at the extra obstacles in Sara’s quest, too. Unlike the boys, who are dumped out on their own, Sara isn’t allowed to find her own way, but has to be told what to do by a magical fox. She can’t even do it in her own form. She has to be changed into a cat—and is still forced to drag along her assigned weapon from the picnic basket.

Backwards and in heels, nothing. Try being a ten-pound cat hauling a steel picnic knife across rough country to a monster-infested castle. And then make her have to choose between her one weapon and the magical object she came to find—no hands, no clothes or carrier bag, just her mouth. Being a girl, Norton seems to say, is no picnic.

By this time Norton had started to write female characters with actual agency, but for the most part they were aliens: the reptilian Wyverns, the witches of Estcarp, Maelen the Thassa. Normal human girls in normal human form didn’t (yet) get to play.

At least Sara gets to have an adventure, and succeed at it, too. She even loses her fear of spiders.

I’ll be reading Octagon Magic next: more magic, more kids. Hopefully fewer obstacles for the girl protagonist.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.