Love has no time limits, but life does. Elizabeth Bear gives us a future where life and love and identity have so many more options than they do today.

Man and animals are in reality vehicles and conduits of food, tombs of animals, hostels of Death, coverings that consume, deriving life by the death of others.

—Leonardo da Vinci

Sometime later; maybe tomorrow

My name is Marq Tames, I’m a mathematician, and I’m planning suicide.

Until today, I wasn’t planning. You couldn’t say I was planning. Because I know perfectly well that it would be the grossest of irresponsibility to plan my exit . . . at least until Tamar didn’t need me anymore.

You don’t do that to people you love.

You don’t do that to people who love you.

Buy the Book

Deriving Life

Now

“Stop taking your oxy,” Tamar says, skeletal hand on my wrist. There’s not much left of them. Their skin crackles against the back of my fingers when I touch their cheek. Their limbs are withered, but their torso is drum-taut, swollen-seeming. I don’t look. Death—and especially transitional death—is so much prettier in the dramas.

“Fuck that,” I answer.

“Just stop taking the damn bonding hormones.” Their papery cheek is wet. “I can’t stand to see you in this much pain, Marq. Even Atticus can’t help me with it.”

“Do you think it wouldn’t hurt me worse not to be here?”

Tamar doesn’t answer. Their eyelids droop across bruised sockets.

I’m exhausting them.

“Do you think this didn’t hurt people before? Before we could contract for pair-bond maintenance? How do you think people did it then? Do you think losing a spouse was easier?”

Tamar closes their eyes completely.

And no, of course, no, they do not think that. They’d just never paused to think about it at all. We all forget that people in the past were really just like us. We want to forget it. It makes it easier to live with the knowledge of how much suffering they endured.

They endured it because they had no choice.

Tamar avoiding thinking about that is the same as Tamar thinking that I should go away. Stop taking my drugs. Maybe file for divorce. Tamar wants to think there’s a way this could hurt me less. They’re thinking of me, really.

I’ve already stopped taking the oxy. I haven’t told Tamar. It helps them to think there’s something more I could do. That I’m just being stubborn. That I’m in charge of this pain.

That I have a choice.

I wish I were in charge. I wish, I wish I had a choice. But I don’t need bonding hormones to love Tamar.

I knew how this ended when I signed the contract.

I’m still here.

“Is this what you want?” Tamar asks me. One clawlike hand sweeps the length of the body that used to be so lithe, so strong.

“I just want every second of you I can get,” I say. “I’ll have to do without soon enough.”

Tamar squints at me. I don’t think I’m fooling them, but they’re not going to call me on it.

Not right now. Maybe not ever.

Maybe they’d rather not know for sure.

But the thing is, I don’t want to keep doing this without them. Especially with, well, the other stuff that’s going on.

I knew Tamar’s deal before we got involved. It was all in the disclosures. I knew there were limits on our time together.

But you tell yourself, going in, that it’ll be fine. That fifteen years is better than no years and hey, the course might be slow; you might get twenty. Twenty-two. How many relationships actually last twenty-two years?

And there are benefits to being the spouse of someone like Tamar, just as there are benefits to having a Tenant.

Something is better than nothing. Love is better than loneliness. And it’s not like anybody gets a guarantee.

So you tell yourself that you can go into this guarded. Not invest fully, because you know there’s a time limit. And that it might even be better because of that, because it can’t be a trap for a lifetime.

There’s life after, you tell yourself.

So much life.

Except then after comes, and you discover that maybe the Mythic After Time isn’t what you wanted at all. You just want now to keep going forever.

But now won’t do that. Or rather, it will. But the now you want to keep is not the now you get. The now you get is a river, sweeping the now you wanted eternally back toward the horizon disappearing behind you.

Evangeline doesn’t sit behind her desk for our sessions. In fact, her desk is pushed up against the wall in her office, and she usually turns her chair around and sits down in it facing me, her back to the darkened monitor. I’m usually over on the other side of the room, next to a little square table with a lamp.

Evangeline’s my transition specialist. She’s a gynandromorph—from environmental toxicity, rather than by choice—and she likes archaic pronouns and I try to respect that.

I’m legally mandated to see her for at least a year before I make my final decision. It’s been eighteen months, because I started visiting her a little before Tamar went into hospice. So I could make my decision tomorrow.

If I thought Evangeline would sign off on it yet. Which she won’t.

Today she isn’t happy. I can tell because she keeps fidgeting with her wedding rings, although her face is smooth and affectless.

She’s unhappy because I just said something she didn’t like.

What I’d said was, “If you change who you are so that someone will love you, and you’re happy afterward, is that so terrible?”

Transition specialists aren’t supposed to let you know when you’ve rattled their cages, but her disapproval is strong enough that even if she doesn’t demonstrate it, I can taste it. I wonder if there are disapproval pheromones.

“Well,” she says, “it seems like you have a lot of choices to consider, Marq. Have you come up with a strategy for assessing them?”

I didn’t answer.

She didn’t frown. She’s too good at her job to frown.

She waited ninety seconds for me to answer before she added, “You know, you do have a right to be happy without sacrificing yourself.”

Maybe it was supposed to hit me like an epiphany. But epiphanies have been thin on the ground for me recently.

“The right, maybe,” I answered. “But do I have the ability?”

“You’ll have to answer that,” she said, after another ninety seconds.

“Yeah,” I said. “That’s the problem in a nutshell, right there, isn’t it?”

Robin, my non-spouse partner, picks me up in the parking lot, and they’re not happy with me either.

Opening salvo: “You need to drop this thing, Marq.”

“This thing?”

Robin waves at the two-story brick façade of the clinic.

“Becoming a Host?”

They nod. Hands on the steering wheel as legally mandated, but I’m glad the car is handling the driving. Robin’s knuckles are paler brown than the surrounding flesh, their face drawn in determination. “You can’t do this.”

“Tamar did.”

“Tamar is dying because of it.”

“Do you think I don’t know that? I’m fifty-six years old, Robin. Another twenty-five years or so in guaranteed good health seems pretty attractive right now.”

Robin sighs. “It’s maybe twenty years of good health if you’re lucky, and you know it. You always walk out of that office spoiling for a fight.”

I think about that. It might be true. “That might be true.”

We drive in silence for a while. We have a dinner date tonight, and Robin brings me home to the bungalow Tamar and I used to share. My bungalow now. I’ll inherit the marital property, though not Tamar’s Host benefits. It’s okay. Once they’re gone, I’ll have my own.

Or Robin and Tamar will win, and I’ll go back to work. The house is paid for anyway. It’s a gorgeous little Craftsman, relocated up here to the 51st parallel from Florida before the subtropics became uninhabitable. And before Florida sank beneath the waves. It got so it was cheaper to move houses than build them for a while, especially with the population migrations at the end of the twenty-first century and the carbon-abatement enforcement. Can you imagine a planet full of assholes who used to just . . . cut down trees?

Tamar liked it—Tamar likes it—because that same big melt that put our house where it is also gave us the Tenants. Or—more precisely—gave them back.

Robin parks, and we walk up the drive past late-summer black-eyed Susans and overblown roses that need deadheading. I let us in, and we walk into the kitchen. Robin’s brought a bottle of white wine and the makings for a salad with chickpeas and pistachios. I rest on a stool while they cook, moving around my kitchen like they spend several nights a week there—which they do.

Tamar approved heartily of me bringing home a gourmet cook. My eyes sting for a moment, with memory. I bury my face in my wine glass until I feel like I can talk again.

“I could keep a part of Tamar with me if I do this. You know that. I could get a scion of Atticus, and have a little bit of Tamar with me forever.”

“Or you could let go,” Robin says. “Move on.”

“Live here alone.” If I had a scion, I wouldn’t be alone.

“It’s a nice house,” Robin says. “You have a long life ahead of you.” They slide a plate in front of me, assembled so effortlessly it seems like a few waves of the hand have created a masterpiece of design. “Being alone isn’t so bad. Nobody moves your stuff.”

Robin likes living alone. Robin likes having a couple of lovers and their own place where they spend most nights by themself. Robin doesn’t get that other than Tamar—and, I suppose, Atticus—I have been alone my whole life, emotionally if not physically, and the specter of having to go back to that, having to return to that loneliness after seventeen years of relief, of belonging, of having a place . . .

I can’t.

I can’t. But I just have to. Because I don’t have a choice.

I poke my food with my fork. “The future I wanted was the one with Tamar.”

Everything about the salad is perfect and perfectly dressed. Robin did the chickpeas themself; these never saw the inside of a can. Their buttery texture converts to sand in my mouth when I try to eat one.

“And you had it.” Robin picks up their own plate and hooks a stool around with one foot, joining me informally at the counter. “Paid in full, one future. I’m not saying you don’t get to grieve. Of course you do. But the world isn’t ending, Marq. Soon, once you get beyond the grief, you will have to look for a new future. Futures chain together, one after the other. You don’t just sing one song or write one book and then decide never to create anything again.”

“Some people do exactly that, though. What about Harper Lee?”

Robin blows on a chickpea as if it were hot. “No feeling is final. No emotion is irrevocable.”

“Some choices are.”

“Yes,” Robin says. “That’s what I’m afraid of.”

Seventeen years, two months, and three days ago

“Caring for a patient consumes your life,” this beautiful person I’d just met was saying.

I was thirty-nine years old and single. Their name was . . . their name is Tamar.

I studied them for a minute, then sighed. “I feel like you’re trying to tell me something,” I admitted. “But I need a few more verbs and nouns.”

“Sorry,” Tamar said. “I’m not trying to beat around the bush. I’m committed to being honest with potential partners, but I also tend to scare people off when I tell them the truth.”

“If I’m scared off, I’ll still pay for your drink.”

“Deal,” they said. And drained it. “So here’s the thing. I’m a zombie. A podling. A puppethead.”

“Oh,” I said. I studied their complexion for signs of illness and saw nothing except the satin gleam of flawless skin. “I’m not a bigot. I don’t . . . like those words.”

Tamar watched me. They waved for another drink.

“You have acquired metastatic sarcoma.”

“I have a Tenant, yes.”

“I’ve never spoken with somebody . . .” I finish my own drink, because now I can’t find the nouns. Or verbs.

“Maybe you have,” Tamar said. “And you just haven’t known it.”

Tamar’s new drink appeared. They said, “I chose this path because I grew up in a house where I was a caretaker for somebody who was dying. A parent. And I have a chronic illness, and I never want to put anyone else in that position. No one will ever be trapped because of me.”

They took a long pull of their drink and smiled apologetically. “My life expectancy wasn’t that great to begin with.”

“Look,” I said. “I like you. And it’s your life, your choice. Obviously.”

“Makes it hard to date,” they said resignedly. “Even today, everybody wants a shot at a life partner.”

“Nothing is certain,” I said.

“Death and global warming,” they replied.

“I would probably have let my parent die, in your place,” I admitted. One good confession deserved another. “They were awful. So. I come with some baggage and some land mines, too.”

Now

“I’ve done so many things for you,” Tamar says. “This thing—”

“Dying.” Still dodging the nouns. Still dodging the verbs.

“Yes.” Their face is waxy. At least they’re not in any pain. Atticus wouldn’t let them be in pain. “Dying is a thing I need to do for myself. On my own terms. You need to let it be mine, Marq.”

I sit and look at my hands. I look at my wedding ring. It has a piece of dinosaur bone in it. So does Tamar’s, the one they can’t wear anymore because their hands are both too bony and too swollen.

“You’re healthy, Marq.” Tamar says.

I know. I know how lucky I am. How few people at my age, in this world we made, are as lucky as I am. How amazing that this gift of health was wasted on somebody as busted as me.

What if Tamar had been healthy? What if Tamar were outliving me? Tamar deserved to live, and Tamar deserved to be happy.

I was just taking up space somebody lovable could have been using. The air I was breathing, the carbon for my food . . . those could have benefited somebody else.

“You make me worthy of being loved.” I take a breath. “You make me want to make myself worthy of you.”

“You were always lovable, Marq.” Their hand moves softly against mine.

“I don’t know how to be me without you,” I say.

“I can’t handle that for you right now,” Tamar says. “I have to die.”

“I keep thinking I can . . . figure this out. Solve it somehow.”

“You can’t derive people the way you derive functions, Marq.”

I laugh, shakily. I can’t do this. I have to do this.

“You said when we met that you never wanted to be a burden on somebody else.” As soon as it’s out I know it was a mistake. Tamar’s already gaunt, taut face draws so tight over the bones that hair-fine parallel lines crease the skin, like a mask of the muscle fibers and ligaments beneath.

Tamar closes their eyes. “Marq. I know how hard it is for you to feel worthy. But right now . . . if you can’t let this one thing be about me, you need to be someplace else.”

“Tamar, I’m sorry—”

“Go away,” Tamar says.

“Love,” I say.

“Go away,” they say. “Go away, I don’t love you anymore, I can’t stand to watch somebody I love go through what you’re going through. Marq, just go away. Let me do this alone.”

“Love,” I say.

“Don’t call me that.” Eyes still closed, they turn their face away.

Sixteen years, eight months, and fifteen days ago

I took Tamar to the gorge.

I’d never taken anybody to the gorge before. It’s my favorite place in the world, and one of the things I love about it is that it’s so private and inaccessible. If you love something, and it’s a secret, and you tell two people, and they love it, and they tell two people . . . well, pretty soon it’s all over the net and it’s not private anymore.

We sat on the bridge over the waterfall—I think it must have been somebody’s Eagle Scout project, and so long ago that nobody maintains the trail up to it anymore. It was a cable suspension job, and it swayed gently when we lowered ourselves to the slats.

The waterfall was so far below that we could hear each other speak in normal tones, and the spray couldn’t even drift up to jewel in Tamar’s hair.

There were rainbows, though, shifting when you turned your head, and I turned my head a lot, because I was staring at Tamar and pretending I wasn’t staring at Tamar.

Tamar was looking at their hands.

“I used to come up here as a kid,” I said. “To get away.”

“How on earth did you ever find it?” They kicked their feet like a happy child.

“It was less overgrown then.” My hands were still sticky from cutting through the invasive bittersweet to get here. I was glad I’d remembered to throw the machete I used for yard work in the trunk. And to tell Tamar to wear stout boots.

“Where did you live?”

I pointed back over my shoulder. “That way. The house is gone now, thank God.”

“Burned down?”

“No, they took it apart to make . . . something. I didn’t care. I was long gone by then.” Tamar already knew I’d left at eighteen and never looked back. “This was the closest thing I had to a home.”

“How long do you think this has been here?”

I shrugged. “Since the Big Melt? It will probably be here forever now. At least until the next Ice Age.”

I saw the corner of Tamar’s smile out of the corner of my eye. “You’re showing me your home?”

The idea brought me short I kicked my own feet in turn. “I guess I am.”

We looked at rainbows for a little while, until a cloud went over the sun.

“You were sexy with that machete,” Tamar said, and looked up from their folded hands into my eyes.

We both reeked of tick spray.

And they kissed me anyway.

Now

I go home.

I sit on the couch we picked out together. There’s music playing, because I don’t seem to have the energy to turn it off. My feet are cold. I should go and get socks.

Part of the problem is not having anywhere to be. I shouldn’t have taken that family medical leave. Except if I hadn’t, what use exactly would I be to my students and the college right now?

Fifteen minutes later, my feet are even colder. I still haven’t found the wherewithal to go and get the socks. My phone beeps with a message and I think maybe I should look at it.

Ten minutes later, it beeps again. I pick it up without thinking and glance at the notifications.

I drop the phone.

Marq, this is Tamar’s Tenant, Atticus.

We need to talk.

I fumble it back up again. The messages are still there. Still burning at me while the day grows dim. The ground and the sky outside seem to blur into each other.

I’ve spoken with Atticus before. We were in-laws, after a fashion. But not recently. Recently . . . I’ve been avoiding it. Avoiding even thinking about it.

Avoiding even acknowledging its existence.

Because it’s the thing that is killing my spouse.

I get up. I put socks on. I start a pot of tea, and though I usually drink it plain, today I put milk and sugar in.

I need to answer this text. Maybe Atticus can help me. Help me explain to Tamar.

Maybe Atticus can help me with my transition specialist.

But when I slide my finger across the screen, a tremendous anxiety fills me. I type and delete, type and delete.

Nothing is right. Nothing is what I mean to say.

I think about what I’m going to text back to Atticus for so long that I do not text it back at all. It’s not so much that I talk myself out of it; it’s just that I’m exhausted and profoundly sad and can’t find much motivation for anything, and despite the tea and sugar I transition seamlessly from lying on the sectional staring at the popcorn texture of the ceiling to a deep sleep punctuated by paranoid nightmares that are never quite bad enough to wake me completely.

Sunrise finds me still on the sofa, eyes crusty and neck aching. Texts still unanswered, and now it feels like too much time has gone by, even though I tell myself I do want to talk to Atticus. Other than me, it’s the being in the world who loves Tamar most, at least theoretically. I’m just anxious because I’m so sad. Because the situation is so fraught.

Because I’m furious with Atticus for taking Tamar away from me, even though I know that’s not reasonable at all. But since when are brains and feelings reasonable?

And it’s dying along with Tamar, although I’m sure it has cells in stasis for eventual reproduction. I know that Atticus has at least two offspring already, because I’ve met them and their Hosts occasionally.

That should comfort me a little, shouldn’t it? That some bit of Tamar is immortal, and will carry on in those Tenants, and their offspring on down the line? And maybe, if I am convincing enough, in me.

I think of my own parent’s blood in me, of my failure to reproduce. Isn’t it funny how we phrase that? Failed to reproduce. I didn’t fail. I actively tried not to. It was a conscious choice.

Childhood is a miserable state of affairs, and I wouldn’t wish it on anybody I loved.

I gave up trying to win my parent’s affection long before they died. I gave up trying to be seen or recognized.

I settled for just not fighting anymore.

Sixteen years, eight months, and sixteen days ago

I reached over in the darkness and stroked Tamar’s hair. It had a wonderful texture, springy in its loose curls. Coarse but soft.

“You’re thinking, Marq,” they said.

“I’m always thinking.”

I heard the smile in Tamar’s voice as they rolled to face me. “It’s not good for you if you can’t turn it off once in a while, you know. What were you thinking about?”

“You . . . Atticus.”

“Sure. There’s a lot to think about.” They didn’t sound upset.

“Do you remember?”

A huff of thoughtful breath. A warm hand on my side. “Remember?”

“All of Atticus’s other lives?”

Tamar made a thoughtful noise. “That’s a common misconception, I guess. Atticus itself didn’t have other lives. It’s a clone of those older Tenants, so in a sense—a cellular sense—the same individual. The Tenants only bud when they choose to, which is why those first Hosts were so unlucky. The Tenants knew infecting them without consent was unethical.”

“But the alternative was to let their species die.” I thought about that. What I would do. If it were the entire human race on the line.

Tamar said, “I can assure you, one of the reasons the Tenants work so hard for us is that they have a tremendous complex of guilt about that, and still aren’t sure they made the right decision.”

Who could be? Let your species die, or consume another sentient being without its consent?

What would anyone do?

Tamar said, “And it’s true that we do share experiences. It can’t perceive the world outside my body without me, after all—the same way I can perceive my interior self much better through its senses. And it has—there’s some memory transferred. More if you use a big sample of the parent Tenant to engender the offspring. Though that’s harder on the Host.”

“So it—you—don’t remember being a Neanderthal.”

More than a huff of laughter this time; an outright peal. “Not exactly. It can share some memories with me that are very old. I have a sense of the Tenants’ history.”

It had been before I was born: The lead paleoanthropologist and two others working on several intact Homo neanderthalensis cadavers that had been discovered in a melting glacier had all developed the same kind of slow-growing cancer. That had been weird enough, though by then we knew about contagious forms of cancer—in humans, in wolves, in Tasmanian devils.

It got weirder when the cancers had begun, the researchers said, to talk to them.

Which probably would have been dismissed as crackpottery, except the cancer also cured that one paleobotanist’s diabetes, and suddenly they all seemed to have a lot of really good, coherent ideas about how that particular Neanderthal culture operated.

What a weird, archaic word, glacier.

I said, “It just seems weird that I’m in bed with somebody I’ve never met.”

As I said it I realized how foolish it was. Anytime you’re in bed with somebody, you’re in bed with everybody who came before you—everybody who hurt them, healed them, shaped them. All those ghosts are in the room.

Tamar’s Tenant was just a little less vaporous than most.

A rustle of sliding fabric as Tamar sat upright. “Do you want to?”

Now

“I’m sorry, Mx. Tames, but you’re not on the visitor list anymore.”

“But Tamar—”

“Mx. Sadiq specifically asked that you not be admitted, Mx. Tames.” The nurse frowns at me, their attractive brown eyes crinkling kindly at the corners.

I stare. I feel like somebody has just thrust a bayonet through me from behind. Like my diaphragm has been skewered, is spasming around an impalement, and nothing—not breath nor words—will come out until someone drags it free.

The bayonet twists and I get half a breath. “But they’re my spouse—”

“They named you specifically,” the nurse says again. They glance sideways. In a lowered voice, dripping with unexpected sympathy, they say, “I’m so sorry. I know it doesn’t make it easier for you, but sometimes . . . sometimes, toward the end, people just want to be alone. It can be exhausting to witness the pain and fear of loved ones. Do you have other family members you could contact? It’s not my place to offer advice, of course—”

I waved their politeness away with one hand. “You have more experience with this sort of thing than I . . . than I . . . thank . . .”

The sobs spill over until they are nearly howls. I bend over with my hands on my knees, doubled in pain. Gasping. Sobbing. I try to stand upright and wobble, catching my shoulder on the wall. Then someone has dragged a chair over behind me and the nurse is guiding me gently into it, producing a box of Kleenex, squeezing my shoulder to ground me.

Surprisingly professional, all of it.

Well, this is an oncology ward. I guess they have some practice.

“Mx. Tames,” the nurse says when I’ve slowed down and I’m gasping a little. “Is there another family member we can call? I don’t think you ought to go home alone right now.”

One of the things that drew me to Tamar was their joy. They were always so happy. I mean, not offensively happy—not inappropriately happy or chirpy or obnoxiously cheerful. Just happy. Serene. Joyful.

It was infectious.

Literally.

Tamar’s relationship with Atticus gave them purpose, and that was part of it. It also gave them a financial cushion such that they could do whatever they wanted in life—pursue art, for example. Travel. (And take me with them.) Early on, the Tenants had bargained with a certain number of elderly, dying billionaires; another decade or so of pain-free, healthier life . . . in each case, for a portion of their immense fortune.

And then there were the cutting edge types, the science-sensation seekers who asked to get infected because it was a new thing. An experience nobody else had. Or because they were getting old, their best and most creative years behind them.

As a mathematician in their fifties, I can appreciate the strength of that motivation, let me tell you.

Some of those new Hosts were brilliant. One was Jules Herbin, who with the help of their Tenant, Maitreyi, went on to found Moth.me.

Herbin was not the only Host who built a business empire.

The Tenants had had a hundred years to increase those fortunes. The Tenants, as a collective—and their Hosts, by extension!—did not lack for money. Sure, there were still fringe extremists who insisted that the Tenants were an alien shadow government controlling human society and that they needed to be eradicated, but there hadn’t been a lynching in my lifetime. In North America, anyway.

And there are still fringe extremists who insist the earth is flat. The Tenants have brought us a lot of benefits, and they insist on strict consent.

For Tamar, those benefits included being able to be pain-free and energetic, which is not a small thing when, like Tamar, you’ve been born with an autoimmune disorder that makes you tired and sore all the time.

And Atticus used its control over Tamar’s endocrine system to make them truly, generously happy. Contented. Happy in ways that perhaps evolution did not prepare people for, when we were born into and shaped by generations of need and striving.

Atticus helped Tamar maintain boundaries, make good life choices, and determine the course of their life. It supported them in every conceivable way. In return, Tamar provided Atticus with living space, food, and the use of their body for a period every day while Tamar was otherwise sleeping. That took a little getting used to. But Tamar explained it to me as being similar to dolphins—half their brain sleeps while the other half drives.

The Tenants really are good for people.

It’s just that they also consume us. No judgment on them; we consume other living things to survive, and they do it far more ethically than we do. They only take volunteers. They make the volunteers go through an extensive long-term psychological vetting process.

And they take very good care of us while they metastasize through our bodies, consuming and crowding out every major organ system. They want us to live as long as possible, of course, because the life span of the Tenant is delineated by the life span of the Host. And yes, when they metastasize into a new Host, they take some elements of their old personality and intellect along with them—and some elements of the personality and identity of every previous Host, too. And they often combine metastatic cells from two or more Tenants to create a combined individual and make sure experiences and knowledge are shared throughout their tribe.

They’ve been a blessing for the aged and terminally ill. And even for those who are chronically ill, like Tamar, and choose a better quality of life for a shorter time over a longer time on earth replete with much more pain and incapacity.

A lot of people with intractable depression have signed up for Tenancy. Because they just want to know what it’s like to be happy. Happy, and a little blind, I guess. It turns out that people with depression are more likely to be realistic about all sorts of things than those with “normal” neurochemistry.

Depression is realism.

The Tenants offer, among other things, an escape from that. They offer safety and well-being and not having to take reality too seriously. They offer the possibility that whatever you’re feeling right now isn’t as good as it gets.

They can change you for real. They can make you happy.

My reality, right now, is that the love of my life is dying, and doesn’t want to talk to me.

Sixteen years, eight months, and fifteen days ago

Atticus, it turned out, talks most easily by texting. Or typing. It could take direct control of Tamar’s voice—with their permission—but all three of us thought that would be weird. And would probably make me feel like the whole puppethead thing was more valid than I knew it to be. So we opened a chat, and Tamar and I sat on opposite sides of the room, and had one conversation out loud while Atticus and I had a totally different one via our keyboards.

It wasn’t a very deep conversation. Maybe I had expected it to be revelatory? But it was like . . . talking to a friend of a friend with whom you don’t have much in common.

We struggled to connect, and it was a relief when the conversation ended.

Now

There are protestors as I come into the clinic. They call to me. I resolutely turn my eyes away, but I can’t stop my ears. One weeps openly, begging me not to go in. One holds a sign that says: CHRIST COMFORTS THE AFFLICTED NOT THE INFECTED. There’re all the usual suspects: DOWN WITH PUPPETMASTERS. THE MIND CONTROL IS NOT SO SECRET ANYMORE.

Another has a sign that says GIVE ME BACK MY CHILD.

I wish I hadn’t seen that one.

“There’s a part of me,” I tell Evangeline, “that is angry that Tamar doesn’t love me enough to . . . to stay, I guess. I know they can’t stay; I know the decision was made long ago.”

“Do you feel like they’re choosing Atticus over you?”

“It sent me a text.”

Evangeline makes one of those noncommittal therapist noises. “How did that make you feel?”

“I want to talk to it.”

“You haven’t?”

I open my mouth to make an excuse. To say something plausible about respecting Tamar’s agency. Giving them the space they asked for. I think about. I settle back in my chair.

Do I want a Tenant if I have to lie to get one?

I say, “I’m angry with it. I want to ignore that it exists.”

“Sometimes,” Evangeline says, “when we want something, we want it the same way children do. Without regard for whether it’s possible or not. Impossibility doesn’t make the wanting go away.”

“You’re saying that this is a form of denial.”

“I’m saying that people don’t change who they are, at base, for other people—not healthily. People, instead, learn to accommodate their differences. While still maintaining healthy boundaries and senses of self.”

“By that definition, the Tenants are not people. We take them on; they make us happy. Give us purpose. Resolve our existential angst.”

“Devour us from the inside out.”

I laugh. “What doesn’t?”

This time, Robin comes inside for me instead of waiting to pick me up outside. That makes me nervous, honestly. Robin is not an overly solicitous human being. Maybe they noticed the protestors and didn’t want me to have to walk past them alone?

That hope sustains me until we’re in the car together, side by side, and Robin says the four worst words in the English language. “We need to talk.”

“Okay,” I say, in flat hopelessness.

“I can’t do this anymore,” Robin says. “It isn’t working out for me.”

You’d think after the third or fourth bayonet they’d stop hurting so much, going in. They’d have an established path.

Not so.

So now I’m single. Nobody, it turns out, can handle the depth of what I’m feeling about losing Tamar. Not Tamar, not Robin.

Not me.

Evangeline can, though. Evangeline can because of proper professional distance. Because she’s not invested.

Because the only person putting the weight of their emotional needs on the relationship is me.

From the edge of the brocade armchair, I speak between the fingers I’ve lowered my face into. “This is a way for me to be with them forever.”

“I can see how it would feel that way to you,” Evangeline answers.

“I need someone to tell me that I am more than merely tolerated. I need to be valued,” I say.

“You’re valuable to them. To the Tenants.”

“You begin to understand,” I say. “Maybe I shouldn’t need this. But I can’t survive these feelings without help. It’s not just that I want to be with Tamar. It’s that I need to not be in so much pain.”

She nods. I’m already on six kinds of pills. Are they helping? They are not helping.

I’m already trying to change myself so somebody will love me better.

So that I will love me better.

Evangeline says, “We need what we need. Judging ourselves doesn’t change it. Sometimes a hug and a cookie right now mean more than a grand gesture at some indeterminate point in the future.”

“What if we make an irrevocable decision to get that hug and that cookie?”

Evangeline lifts her shoulders, lets them fall. “My job is to make sure that you’re making an educated decision about the costs and benefits of the cookie. Not to tell you how much you should be willing to pay for it.”

I pace the house. I rattle pots in the kitchen but don’t cook anything. I take an extra anxiety pill.

When it’s kicked in, I pull out my phone and text Atticus with trembling hands. Sorry about the delay. I needed to get my head on straighter.

I understand. This is hard on all of us.

You have to make Tamar talk to me!

Tamar doesn’t want you to do this. I have to honor their wishes.

Even after they’re dead?

Especially after they’re dead.

I can’t do this alone.

We love you, the cancer says. We will always love you.

Tell Tamar I stopped taking the oxy, I type, desperate. Tell them I did what they asked. Tell them to please just let me come say goodbye.

I’m talking to the bloated mass that disfigures Tamar’s strong, lithe body. It isn’t them.

Except it is them.

And Atticus is dying, too, and Atticus is taking the time out to comfort somebody it’s leaving behind. It’s funny, because we never had a lot to say to each other in life. Maybe that was denial on my part as much as anything. But now, it is Tamar.

The only part of them that will still talk to me.

And I want it to be me as well.

I will tell them, Atticus types. I will tell them when they wake.

They that are not busy being born are busy dying.

What’s the value of an individual? What is the impact of their choices? What is our responsibility for the impact of our choices on others? What is our responsibility to deal with our own feelings?

We’re responsible for what we consume, right? And the repercussions of that consumption, too. If the Big Melt taught us anything, as a species, it taught us the relentless ethics of accountability.

So from a certain point of view, the Tenants owe me.

We love you.

Tamar is gone. The call came in the morning. The Tenants will be handling the arrangements, in accordance with Tamar’s wishes.

Atticus, of course, is also gone.

I don’t know if Tamar woke up after I talked to Atticus. I don’t know if Atticus got a chance to tell them.

The house belongs to me now.

I should find some energy to clean it.

To Evangeline, I say, “What if you knew that if you changed yourself—let someone else change you, I suppose—you would be loved and valuable?”

“I’d say you are lovable and valuable the way you are. Changing yourself to be what someone else wants won’t heal you, Marq.”

I shake my head. “I’d say that people do it all the time. And without the guarantee the Tenants offer. Boob job, guitar lessons, fix your teeth, dye your hair, try to make a pile of money, answer a penis enlargement ad, lose weight, gain weight, lift weights, run a fucking marathon. They fix themselves and expect it will win them love.”

“Or they find love and expect it to fix them,” Evangeline offers gently. “Or sometimes they give love, and expect it to fix the beloved. If love doesn’t fix you, it’s not true love, is that what you’re suggesting?”

“No. That only works if you’re one of them.”

She laughs. She has a good laugh, throaty and pealing but still somehow light.

“I had true love,” I say more slowly. “It didn’t fix me. But it made me lovable for the first time.”

“You were always lovable. Maybe Tamar helped you feel it?”

“When you grow up being told over and over that you’re unlovable, and then somebody perfect and joyous loves you . . . it changes the way you feel about yourself.”

“It’s healing?” she suggests.

“It made me happy for a while.”

“Did it?”

“So happy,” I say.

She nibbles on the cap of her pen. She still uses old-fashioned notebooks. “And now?”

“I can never go back,” I tell her. “I can only go forward from here.”

Robin still picks me up after my sessions. They said they still cared about me. Still wanted to be friends. They expressed concern about when I’m coming back to the university and whether they would like me to facilitate the bereavement leave.

They’re in HR; that’s how we met in the first place.

I want to shove their superciliousness down their throat. But I also do not want to be alone. Especially today, when we are going to the funeral.

Without Robin, I think I would be. Alone. Completely.

I don’t have a lot of the kind of friends you can rely on for emotional support. Maybe that’s one reason I leaned so hard on Tamar. I didn’t have enough outside supports. And I’ve eroded the ones I did have by being so broken about Tamar dying.

Don’t I get to be broken about this? The worst thing that’s ever happened to me?

When we’re in the car, though, Robin turns to me and says, “I need to confess to something.”

I don’t respond. I just sit, stunned already, waiting for the next blow.

“Marq?”

From a million miles away, I manage to raise and wave a hand. Continue.

“I wrote to the Tenant’s candidate review board about you. I suggested that you were recently bereaved and they should consider your application in that light.”

I can’t actually believe it. I turn slowly and blink at them.

“You what?”

“It’s for your own good—”

I stomp right over their words. “You know what’s for my own good? Respecting my fucking autonomy.”

“Even if it gets you killed?”

“It’s my life to spend as I please, isn’t it?”

Silence.

I open the car door. The motor stops humming—a safety cutoff. We hadn’t started rolling yet, which is the only reason the door will open.

“If it meant I wouldn’t go, would you come back to me?”

That asshole turns their face aside.

“Right,” I say. “I’ll find my own way home, I guess. Don’t worry about coming to the funeral.”

It’s a lovely service. I wear black. I sit in the front row. I used an autocar to get here. I don’t turn around to see if Robin showed up. I stand in the receiving line with Tamar’s siblings and the people who are Hosting Atticus’s closest friends. Robin is there. They don’t come up to me. Nobody makes me talk very much.

I drink too much wine. Tamar’s older sib puts me in an autocar and the autocar brings me home.

I can’t face our bedroom. The Tenants made sure the hospital bed was removed weeks ago, when Tamar went into hospice and we knew they were not coming home. So there’s nothing in our sunny bedroom except our own bedroom furniture.

I can’t face it alone.

I put the box with Tamar’s ashes on the floor beside the door, and I lie down on the sofa we picked out together, and I cry until the alcohol takes me away.

Tomorrow, which is now today

It’s still dark out when I wake up on the couch. Alone. I fell asleep so early that I’ve already slept eleven hours. I’m so rested I’m not even hungover. No point in trying to sleep more, although I want to seek that peace so fiercely the desire aches inside me.

There are other paths to peace.

I stand up, and suddenly standing is easy. I’m light; I’m full of energy. Awareness.

Purpose.

I pick up my phone by reflex. I don’t need it.

There’s a message light blinking on the curve.

A blue light.

Tamar’s favorite color. The color I used especially for them.

I’ve never been big on denial. But standing there in the dark, in the empty house, I have a moment when I think—This was all a nightmare, it was all a terrible dream. My hand shakes and a spike of pure blinding hope is the bayonet that transfixes me this time.

Hope may be the thing with feathers. It is also the cruelest pain of all.

Tamar’s ashes are still there in the beautiful little salvaged-wood box by the door.

The hope is gone before it has finished deceiving me. Gone so fast I haven’t yet finished inhaling to gasp in relief when my diaphragm cramps and seizes and I cannot breathe at all.

I should put the phone down. I should walk out the door and follow the plan I woke up with. The plan that filled me with joy and relief. I shouldn’t care what Tamar has to say to me now when they didn’t care what I needed to say to them then.

I put my right thumb on the reader and the phone recognizes my pheromones.

Marq, I love you.

I’m sorry I had to go and I’m sorry I had to go alone.

You were the best thing that happened to me, along with Atticus. You were my heart. You always talked about my joy, and how you loved it. But I never seemed able to make you understand that you were the source of so much of that joy.

I know you will miss me.

I know it’s not fair I had to go first.

But it comforts me to know you’ll still be here, that somebody will remember me for a while. Somebody who saw me for myself, and not just through the lens of Atticus.

I lied when I said I didn’t love you anymore, and it was a terrible, cruel thing to do. I felt awful and I did an awful thing. I do love you. I am so sorry that we needed different things.

I am so sorry I sent you away.

Atticus is arranging things so that this will be sent after we’re gone. I’m sorry for that, too, but it hurts too much to say goodbye.

Do something for me, beloved?

Don’t make any hasty choices right now. If you can, forgive me for leaving you and being selfish about how I did it. Live a long time and be well.

Love (at least until the next Ice Age),

Tamar

I stare at the phone, ebullience flattened. Hasty choices? Did Tamar know I was applying for a Tenant? Had Atticus found out somehow?

Or had they anticipated my other plan?

I had a plan and it was a good plan—no. Dammit, concrete nouns and concrete verbs, especially now.

I had been going to commit suicide. And now, Tamar—with this last unfair request.

Forgive them.

Forgive them.

Had they forgiven me?

Fuck, maybe I can forgive them on the way down.

The hike up to the gorge is easier in autumn. The vines have dropped their leaves and I can see to push them aside and find the path beyond. The earth underfoot is rocky and red, mossy where it isn’t compacted. I kick through leaves wet with a recent rain. I am wearing the wrong shoes.

I am still wearing my funeral shoes.

It is gray morning at the bottom of the trail. Birds are rousing, calling, singing their counterpoints and harmonies. Dawn breaks rose and gray along the horizon and my feet hurt from sliding inside the dress shoes by the time I reach the bridge. I pause by its footing, catching my breath, leaning one hand on the weathered post. The cables are extruded and still seem strong. A few of the slats have come loose, and I imagine them tumbling into the curling water and rocks far below.

The water sings from behind a veil of morning mist. I can’t see the creek down there, but I feel its presence in the vibration of the bridge, and I sense the long fall it would take to get there. The bridge rocks under my weight as I step out. I could swear I feel the cables stretching under my weight.

How long since I’ve been here?

Too long.

Well, that neglect is being remedied now.

I achieve the middle of the bridge, careful in my slippery, thoughtless shoes. The sky is definitely golden at the east edge now, and the pink fades higher. I turn toward the waterfall. I wondered if there will be rainbows today.

I unzip my jacket and bring out the box I’d tucked inside it when I left the house, the box of Tamar’s—and Atticus’s—mortal remains.

I clear my throat and try to find the right thing to say, knowing I don’t have to say anything. Knowing I am talking to myself.

“I wanted to keep you forever, you know. I don’t want to think about this—about you—becoming something that happened to me once. I don’t want to be a person who doesn’t know how to love themself again. And then I thought, maybe if I made myself like you, I would love myself the way I loved you. And Robin’s not going to let me do that either, I guess . . .

“And you would be unhappy with me anyway, if I did.”

I sniffle, and then I get mad at myself for self-pity.

Then I laugh at myself, because I am talking to a box full of cremains, with a little plaque on the front, while standing on a rickety vintage home-brew suspension bridge over the arch of a forgotten waterfall. Yeah, there’s a lot here to pity, all right.

“So I don’t know what to do, Tamar. I don’t know who to be without you. I don’t know if I exist outside of your perception of me. I liked the me I saw you seeing. I never liked myself before. And now you’re gone. So who am I?

“And okay, maybe that’s unfair to put on somebody. But I did, and you’re stuck with it now.”

I sniffle again.

“You asked me to do something for you. Something hard. God am I glad nobody is here to see this. But I guess this is a thing I have, a thing I am that’s nobody else’s. This place here.”

The sunrise is gaining on the birdsong. Pretty soon it will be bright enough for flying, and they won’t have so much to cheep about because they’ll be busy getting on with their day.

In the end, everything falls away.

Whatever else I have to say is just stalling.

I say, “Welcome home, Atticus. Welcome home, Tamar.”

I kiss the box.

I hold it close to my chest for a moment, steeling myself. And then fast, without thinking about it, I shove my arms out straight in front of me, over the cable, over the plunge.

I let go.

Tamar falls fast.

I don’t see where they land, and I don’t hear a splash.

The damn shoes are even worse on the way back down.

There’s no wireless service until you’re halfway down the mountain. I’ve actually forgotten that I brought the damn phone with me. I jump six inches on sore feet when it pings.

I resist the urge to look at it until I get back to the sharecar. The morning is mine and the birds are still singing. I cry a lot on the way down and trip over things in my funeral shoes. I swear I’m throwing these things away when I get home.

I’d parked the little soap box of a vehicle where it could get a charge when the sun was up. I walk over the small, grassy, ignored parking lot and lean my rump against the warm resin of its fender. The phone screen is easier to read once I shade it with my head.

The ping is a priority email, which makes me feel exactly the way priority emails and four a.m. phone calls always do.

It says:

Congratulations!

Dear Mx. Marq Tames,

On the advice of your transition specialist, you have been selected for expedited compassionate entrance into the Tenancy program, if you so desire. Of course, such entrance is entirely voluntary, and your consent is revocable until such time as the Tenancy is initiated.

Benefits of the program for you include . . .

. . . and then there was a lot of legalese.

Huh.

Evangeline came through.

I guess she and Robin were both doing what they thought was best for me. Funny how none of us seem to have a consistent idea of what that is.

I don’t read the legalese. I start to laugh.

I can’t stop.

I unlock the car. I toss the phone on the floor and lock it again. Then I walk away on sore feet, alternately chuckling to myself and sniffing tears.

I pick a flatter trail this time, and half a mile along it I start wondering about a complicated function I was working on before I went on leave, and whether that one student got their financial aid sorted out.

No matter what choice you make, you’re going to regret it sometime. But maybe not permanently. And it wasn’t like I had to decide right now. I had the day off. Nobody was looking for me.

It was going to be a hot one. And I still had some walking to do.

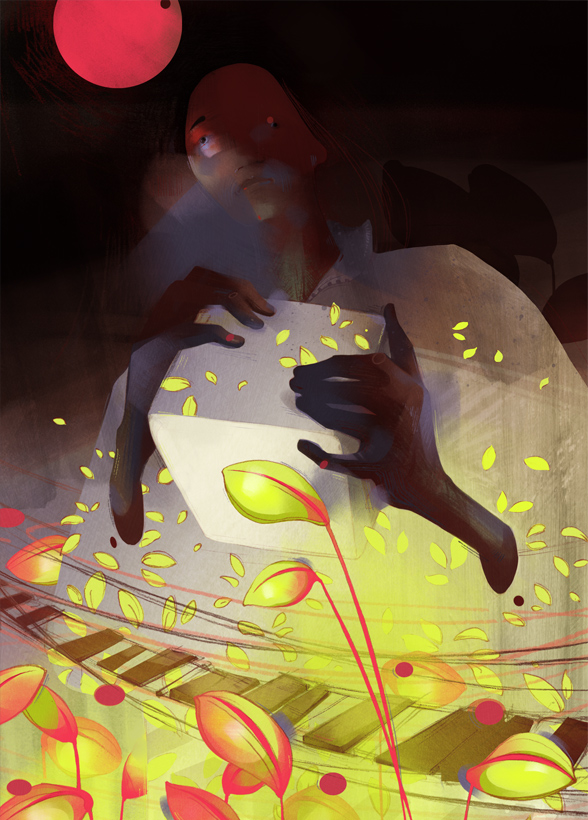

Text copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Bear

Art copyright © 2019 by Mary Haasdyk

Buy the Book

Deriving Life

Good story (even if it’s not quite clear how the Tenants would have evolved intelligence…)

it’s just unbelievable …. i read breathless …. thank you.

I’m crying so hard at the end of this – wow, that was intense

As someone with treatment-resistant depression and multiple chronic pain disorders, and who actively chose not to have children because I would not inflict that agony on another, and who over a year ago became a vegetarian because of the horrific ethics of consuming (obviously non-consenting) sentient beings and that industry’s huge responsibility in the warming of our planet, I was utterly floored by this story. How did an author tap into my very being like this‽ Perhaps I really am not as alone as I feel. How very tempting those Tenants are. What a brilliant concept! A fascinating device to explore these ideas

Really fabulous story. I liked the way things gradually unfolded – and how different people had such different views of helping.

This is beautiful. I’m going to go buy my own copy right now. <3

This was achingly sad but at the same time so very well written and the pain feels so raw and real I was breathless by the time Marq gets to the bridge near the end.

Well written. I can certainly see the attraction of a Tennant. I fell sorry for those poor palaeontologists, though

Speechlessly, in tears of gratitude and respect, I thank you for this beautiful story.

so many layers, so much humanity.

I wonder if it is glorious joy or exhaustion you feel as you put down your pen, and sip cooling tea from your favorite cup.