There’s been an uptick in blowback lately from commenters who take issue with my reading Andre Norton’s works with the eyes of 2019. They explain, with varying degrees of equanimity, that she wrote these books many years ago, and things were different then, and why don’t I understand this? Why must I persist in reading them with the awareness of now instead of then?

That’s what a reread is. I was alive and reading in the Sixties and Seventies, when her for-me most problematical works were published. I read them then with a very different awareness of the world. When I reread them, I see things that weren’t visible to me as a tween and teen. It was indeed a different world. And that’s part of the experience of the reread.

The vast majority of the books I’ve reread have held up even while I note that they are Of Their Time™. A few haven’t. One or two of those really haven’t. For me, there won’t be another reread of those titles, and for readers of this column who haven’t read or reread them yet, maybe it helps to know what they’re getting into if they try. I will however go back joyfully to my favorites, and those are numerous.

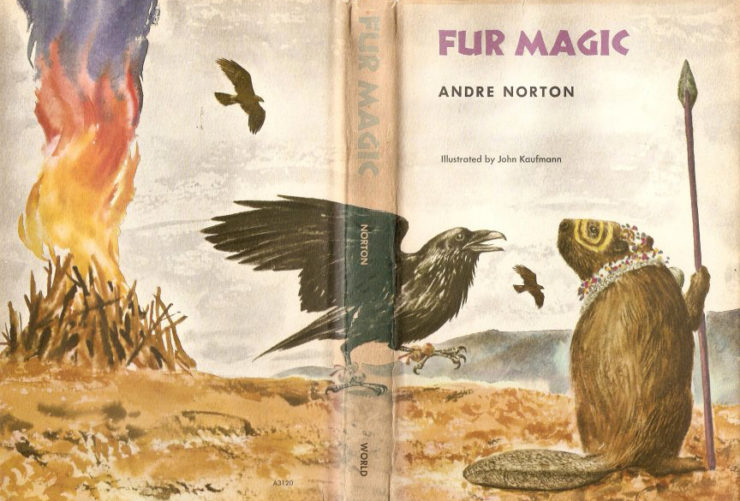

One of them, I’m rather relieved to note, is Fur Magic. The copyright date on the edition I have is 1965, so it’s early on in the series. It reminds me of Steel Magic in that it’s an adventure with a protagonist who turns into an animal, and it’s one of Norton’s Native American fantasies.

Of those, I think, it’s one of her best. It plays to her strengths: boys’ adventure with rapid pacing, carefully constructed alien world, and misfit protagonist who learns useful life lessons in the course of the story. It’s less openly didactic than Steel Magic and Dragon Magic, and to my eye it’s a really good middle-grade fantasy.

I like the way she frames it. Cory’s dad has been deployed to Viet Nam, and he’s spending the summer with his adopted uncle, a rancher who breeds Appaloosa horses in Idaho. Uncle Jasper is a Nez Percé, a member of the tribe that bred these horses. There’s a lot of story about the horses that she doesn’t go into, but she does have quite a bit to say about what happened to his people after the arrival of the white invaders.

Norton has made a point before of showing Native Americans in non-stereotypical roles—notably in Galactic Derelict (1959), where the protagonist, a trained archaeologist, says in so many words that “There’s more to us than just beads and feathers.” Sometimes she misses the mark (The Defiant Agents, particularly), but for the most part, for a white woman in the Fifties and Sixties, she does a pretty good job of educating her presumably white audience.

Cory is thrown into an environment he’s completely unprepared for. He’s a city kid. He’s terrified of horses. He tries to be worthy of his uncle’s respect—he admires Uncle Jasper tremendously—but at the story begins, he just can’t figure out how.

Then he’s given a job: Wait alone at a cabin on the ranch, and be ready to alert his uncle when a guest arrives, the elder Black Elk. While he waits, he wanders around a bit, and falls into a hole that turns out to contain a very old medicine bag. As soon as he realizes what it is, he tries to restore it to its hiding place, but he did open it to investigate. That gets him in trouble when Black Elk arrives.

He’s done a forbidden thing, and he has to make it right. Black Elk sends him back to the time before the Changer overturned the world, when animals ruled and humans were not yet created. When he comes to, he’s sharing the body of a beaver named Yellow Shell.

In this world, animals live the way Native American people lived before the coming of the white man. Yellow Shell’s people are allies with the otters and enemies of the mink. The Changer, who often wears the form of a coyote, is trying to create man, not as the ruler of the animals but as their slave.

Cory’s quest is to find the Changer’s medicine bag and recover his human shape. Along the way he’s captured by the mink, rescues the otter who is his fellow captive, and joins two otters on an embassy to the chief of the eagles. The otters bring a warning of war and change. Cory/Yellow Shell wants to warn the beavers, and does manage to do this, but mostly he wants to go home.

He has to perform a great labor in order to earn the eagles’ help. Once he’s done it, he’s literally dropped off outside Coyote’s house, and he has to find the medicine bag and help prevent Coyote from creating a human slave. In the process he gains the help of Thunderbird, and through him of the Great Spirit. Then at last he can go home, where he’s grown up a great deal and lost his fears.

I was afraid that Cory would end up being the catalyst for the subjugation of the animals, but that didn’t happen. I got the sense that it would in due time, as part of the order of nature, but what Cory does is keep that order from being disrupted by Coyote’s scheming. He’s not an agent of change but one of stability, at least for that age of the world.

There’s strong magic in this book, and it’s not all happy-feelgood even at the end. Black Elk is a complicated character, who might actually be the Changer, but he’s not presented as evil. He’s there to teach Cory a lesson about violating sacred space.

Buy the Book

A Hero Born

Inadvertent or not, what Cory has done is a bad thing, and it’s his responsibility to fix it. Which is a powerful message about what white people have done to the people who were in North America before them.

I don’t remember much about my first read of this book. I remember Yellow Shell and Coyote, but that’s about it. I do recall that it taught me a better understanding of Native American culture at a time when most of us were playing cowboys and Indians. We were taught in school about the conflicts between natives and invaders, but the slant was distinctly pro-white and anti-Native American. Norton’s books showed a different picture.

This book especially holds up because its viewpoint is a young white person. He’s an outsider, and then he’s transformed into basically an alien, which is something Norton was really good at. She knew how to write the nonhuman and the outsider-human. And she knew how to pace an adventure.

Next I’ll be rereading Lavender-Green Magic. This is the one of the series that I remember the best. Will it hold up, or will the Suck Fairy have strewn it with the ashes of regret? Watch this space.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.