Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

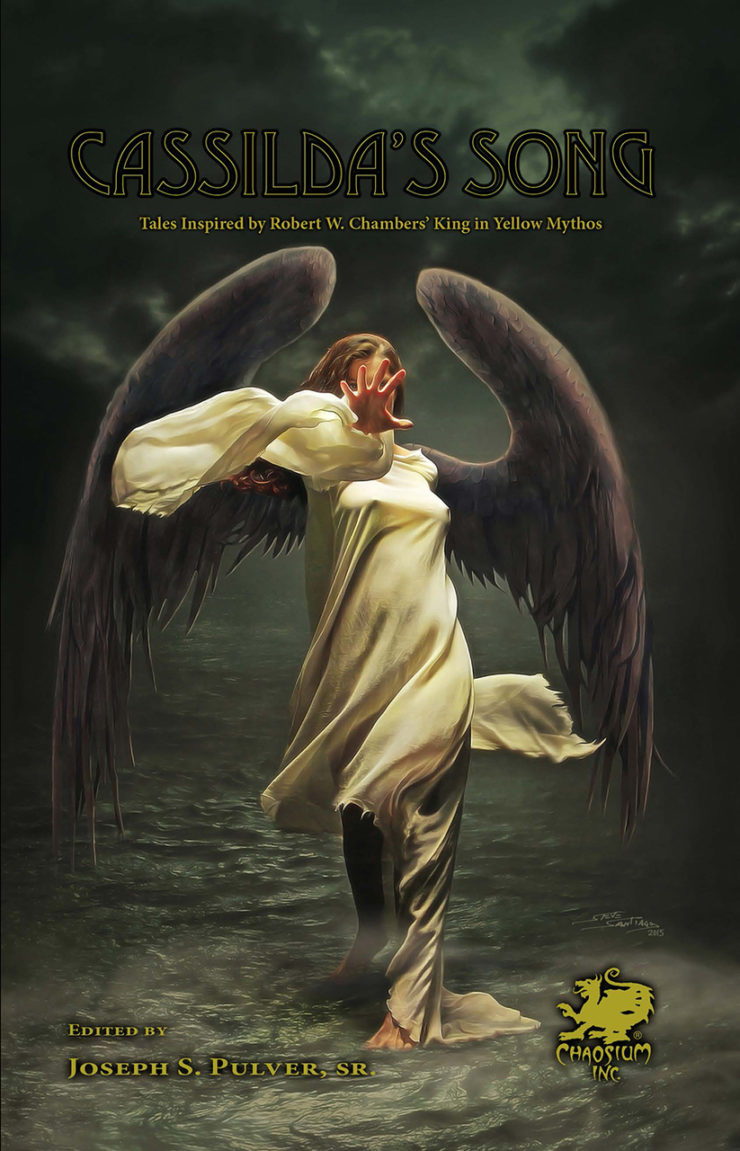

This week, we’re reading Anya Martin’s “Old Tsah-Hov,” first published in Joseph S. Pulver, Sr.’s Cassilda’s Song anthology in 2015. Spoilers ahead.

After tasting the bread of the City of the Sun, no other food could ever fully satisfy…

Summary

Narrator wakes in prison, with two adams staring at him through the bars. He’s been here a while, has heard one adam call the other “Archer” long enough to know that’s the white-coated pricker-prodder’s name. Archer wears a six-pointed sun-colored pin, like the one she used to wear. The pin angers narrator, because it reminds him of her, and how he’s not with her, not in the city where he longs to be. He lunges at the bars, yelling. As ever, the other prisoners yell along.

Undaunted, the adams leave through the door prisoners enter—the one, too, prisoners exit if their offenses are less than narrator’s and they have families to retrieve them. The opposite door’s different. Prisoners who pass through that door never return.

Narrator’s too angry to eat, too afraid to look into his water, for it will reflect the King’s mocking eyes. So he lies down and imagines her scent, her singing, the city of Gold.

Once narrator ran the streets with his brother and sister. Their Ima warned them to avoid strangers who might pick a fight just because they didn’t like the way they smelled. Adams were worse, tall, liable to attack with stones and sticks. Narrator listened dutifully until the day he saw two adults fight. The smaller opponent won, his prize a slab of smoked meat. His color was like narrator’s, something between sun and sand and city; if only narrator could learn to fight like him, he’d never go hungry. Besides, fighting “looked like pure pleasure.”

So narrator made a deal with the so-called King of the Streets, to whom all the others bowed or gave wide berth. In exchange for food, King schooled narrator in battle arts. King praised narrator as a natural fighter.

On the day narrator’s life changes, they stake out a butcher’s stall. King explains he’ll create a distraction. A female customer engages the butcher’s attention, inadvertently aiding the caper. King bites the butcher; narrator steals a beef shank; then everything goes wrong. King snatches the beef, leaving his apprentice to take a hurled rock. Narrator falls, shocked by King’s betrayal. Only the woman’s intervention saves him from the butcher’s further wrath.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

The woman reaches for narrator, who’s never allowed an adam to touch him. This one, however, hums in a voice so soothing and beautiful that he accepts, then enjoys her caresses. She calls herself “Cassilda.” She calls him “Tsah-Hov,” Yellow, and so that’s narrator’s new name.

He follows Cassilda from the market. From an alley King watches, glaring.

Tsah-Hov lives with Cassilda in a tall building, where he sleeps in her bed and listens to her song of the city of the setting sun and of how they share it with their tribes. There it all began, there it will all end, there the city will endure until the descent of a great King from the sky. In their neighborhood, he sees other dogs accompanying adams. In the old market, he sees dogs like he was, who envy his new life. But when he glimpses King, King only turns away as if in pity. At night Tsah-Hov dreams he fights King, and loses, and King admonishes him for getting soft.

Eventually Cassilda mates with an adam named Shmuel, who displaces Tsah-Hov from the bed. They have a little male named Chanan. Cassilda has less time for Tsah-Hov, but sometimes she sings to both him and Chanan, and Tsah-Hov doesn’t feel alone.

Other, worse days Shmuel growls at Cassilda. Once he hits her, and Tsah-Hov wants to tear him apart. Despite King’s goading in his head, he knows Cassilda loves Shmuel too, so he retreats.

Another bad day, he and Cassilda and Chanan are in the market when a bomb falls. Back home Cassilda sings a lament for the city. In Tsah-Hov’s dreams, King just laughs.

The family moves to a place of trees and grass. There are all sorts of dogs there. Like them, Tsah-Hov walks on a leash; unlike them, he hates the leash and thinks with relish of the one time he managed to attack a “prissy one of [his] kind.”

Shmuel and Cassilda are at odds again. Shmuel leaves. He returns one night drunk, frightening Chanan, enraging Cassilda. She confronts Shmuel, who slaps her. Hearing King’s voice shouting “Coward!”, Tsah-Hov attacks Shmuel. Chanan interposes himself, and Tsah-Hov bites not Shmuel’s leg but Chanan’s cheek. Someone clubs him—before Tsah-Hov sees his assailant’s Cassilda, he bites her arm. Mortified, he flees, only to return, for he has nowhere to go without her.

Screeching vehicles arrive. One’s for Cassilda and Chanan. The other’s for Tsah-Hov, who ends up caged in its back.

After that, he’s in the prison. And now Archer’s come for him, with another adam. They bring Tsah-Hov through the door of no return. He struggles, but the adams have had ways to subdue and hurt from the beginning of time. Does Cassilda still think of him? Does she understand?

In the Chamber, Archer needle-pricks him. Tsah-Hov closes his eyes and sees the Yellow City, with Cassilda waiting outside the adams’s gathering house. She sings, opens her arms, then becomes King, no longer bloody but radiant yellow. King drags Tsah-Hov inside, where all is roofless-bright and two suns fill the sky. Cassilda sings, unseen. King hurls Tsah-Hov towards adams bearing many rocks. In chorus they yell, “Kelev Ra!”

Bad dog.

What’s Cyclopean: It’s all about the smells this week. And the half-understood Hebrew, from “kelev ra” to Tsah-hov (as in the King in…)

The Degenerate Dutch: Some very human hatreds shape Tsah-hov’s life.

Mythos Making: This week’s story dances with the King in Yellow mythos, and what it means for eldritch beings to move us with their incidental passions.

Libronomicon: Songs are more important than books this week: Cassilda’s songs of the city, and of things lost and found, and of great kings and beginnings and endings.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The King in Yellow, regardless of his form, tempts his followers into hubris and ruin.

Anne’s Commentary

My cousin Lynn liked to torture me, and she knew exactly how. She’d pick up her guitar and launch into a song called “Old Shep,” which was about a guy and his beloved dog. Okay, fine, until the closing stanzas. Old Shep gets too old, and the guy has to shoot him. Really, Lynn? When you knew how traumatized I was by the Disney movie Old Yeller (based on a traumatizing “children’s” book by Fred Gipson). Old Yeller’s this stray yellow dog who adopts an 1860s farm family and over time saves every family member from bears and wild hogs and rabid wolves and such. You know, the usual 1860s Texas varmints. But the rabid wolf bites Yeller, and Yeller gets rabies and tries to attack the youngest boy, and the oldest boy has to shoot him!

I wouldn’t cry so hard in a theater again until Samwise asked, “Do you remember the Shire, Mr. Frodo?” I’m tearing up now, thinking about doomed rabid Yeller.

So, I go into Martin’s “Old Tsah-Hov” expecting just another cheerful tale about the King in Yellow devastating human lives. That’s because I don’t know Hebrew and didn’t look up the meaning of tsah-hov until too late. It means yellow, people. Hence “Old Tsah-Hov” is the equivalent of “Old Yeller.” Oh no, we’ve gone from triumphant snakes and poisonous plant people to a doomed dog, and I didn’t even get a chance to brace myself because Martin is as sneaky as Lynn promising to sing a cheerful song about teenagers dying in car wrecks, then switching to “Old Shep” mid-verse. Martin keeps the reader uncertain what kind of animal her narrator is until about a third of the way into the story. At first I thought he was a human prisoner. Then I thought he was a monkey, gone from street primate to lab subject. I retained that idea (maybe out of subconscious desperation) until Martin finally let the “dog” out of the bag. And again, it was too late. I had to keep reading.

Semi-kidding aside, the trauma gets worse. For a too-brief time, Tsah-Hov gets to bask in domestic comfort and Cassilda’s undivided love. Then a man barges in and distracts Cassilda. Tsah-Hov deals. Then there’s a baby. Tsah-Hov deals. Then the man turns abusive. Even now, Tsah-Hov deals. God, depressing. Cassilda, wise up! Tsah-Hov, listen to King and take a chunk out of this jerk! But no, things drag on (including a bomb strike on Jerusalem) until a crisis erupts that ends in Cassilda and kid mistakenly bitten and Tsah-Hov euthanized as a kelev ra, bad dog.

All too realistic, this fiction. How does “Old Tsah-Hov” slot into a King in Yellow anthology? Where are the fantastic elements? I guess you could count the animal-as-narrator device, but Tsah-Hov and canine society are handled realistically—for the most part, the narrator’s point of view remains doggy rather than human. So I’m not going to count the narration as fantastic.

However, Martin does give us an intriguingly canine version of King in Yellow mythology, in which the Monarch of Madness is embodied in a tawny street dog named King, as omnipotent in his small realm as is the Yellow King in Carcosa. His disciple/victim is another dog, also yellow of pelt. Cassilda, interestingly, is not a dog but a woman whose entrancing song about a golden city (Jerusalem) and an impending King parallels Cassilda’s usual lyrics about Carcosa and its ruler. Like the mythic King, canine King seduces, then betrays.

Or is it Tsah-Hov who betrays King? Is King’s snatch of the beef shank his abandonment of Tsah-Hov or a tough lesson in the naiveté of trust? Of yielding to one’s rightful master? If so, Tsah-Hov fails King’s test. He surrenders to the charms of a human and leaves behind not only King but his siblings and tribe. He trades the sublimity of the fight for soft living, for collared docility: Except for one much-savored battle with another tame dog, he fights now only in dreams and there he always loses to King. Then we see the apotheosis of King as brilliant lord of the same temple he disparaged in its human imitation as being without food, without meat, therefore not worth entering. Yet to punish Tsah-Hov when he enters King’s temple, where two suns reign as above the Lake of Hali, the “meat” will be Tsah-Hov himself and his butchers a mob of rock-bearing “adams.” The image of a beckoning Cassilda lured Tsah-Hov to the temple; her song still sounds in Tsah-Hov’s ears inside it, as the punisher-adams display their missiles.

Thus “Old Tsah-Hov” qualifies as a horror story, with the hero suffering even beyond the euthanasia table. This is what happens when you accept (however inadvertently) the King in Yellow, then turn from him only to fail the one worshipped in His place. Will stoning clear Tsah-Hov of his misdeeds and allow him to enter a new Yellow City? Or will the stoning go on forever?

Cousin Lynn, are you happy now? Oh, do you remember dim Carcosa, Mr. Frodo?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Okay, I finally figured out what’s been bugging me the whole time I was reading this story. It’s the yellow Star of David pin, which seems like something that would have… unfortunate resonances… for a lot of people in Israel. Gold necklaces sure, pins, sure, but yellow stars that you pin on your clothing? But a quick search shows me that actual Judaica stores sell actual gold Star of David lapel pins, so clearly it’s just me. I’ll just be over here with the Pride flag Star of David nose studs that came up in the same search, much more my speed.1 And with an intriguingly strange story about yellow kings that didn’t deserve my falling down a jewelry-laden rabbit hole.

Rabbits are not entirely irrelevant here; this reminds me of nothing so much as Watership Down, a parallel world where humans are a half-understood source of terror and beneficence and myth. Not quite as much parallel worldbuilding here—Martin’s dogs don’t seem to have a separate language, or as rich a myth-cycle as the stories of El-Ahrairah—but then dogs live lives far more closely entwined with humanity than do rabbits. Their lives are shaped by our kindnesses and cruelty to each other, and our judgments of each other and of them, whether or not they fully understand those things.

The King of the Streets isn’t quite the King in Yellow, either, at least not on his own. The King shares with Yellow forbidden knowledge, and convinces him, Hildred-like, that he has a particular right to take what he wants. That training is ultimately a trick, a way to get the King something he wants, but it also leads Yellow to an unimaginable ascension into an unimagined new world. And, eventually, to an unimaginably terrible fate. That downfall comes via Shmuel, and his treatment of Cassilda.

And there I get distracted by unintended resonances again. Cassilda is primarily a Carcosan name (just ask Google), but after that it’s an Arabic name for a Catholic saint. (It means “to sing,” which is presumably how Chambers originally picked it.) Whereas Shmuel is as Jewish as names get. It means “name of god,” which is probably the intended resonance—and I also see the resonance of taking one of our world’s current archetypal conflicts, showing its impact at both a broad and a personal level, and showing how it affects someone who can’t possibly follow the tangle of wars and un-canine motivations that shape his life. It’s also a story in which a dog dies because a Jewish man abuses… gah, no, wait. She leaves a note at the Western Wall. She wears a Star of David pin. Cassilda is in fact a nice Jewish girl with an Arabic name and terrible taste in men. I’m fine now. Sorry, and I hope you’re all enjoying my roller coaster rabbit holes.

I do like a story where humans are the monstrous source of vast temptations and terrors. It always raises such fascinating questions. Like, if dogs are to humans as humans are to the madness-inducing poets of Carcosa, does that mean humans have evolved in symbiosis with said poets? Plenty of stories have Carcosa as a source not only of terror and authoritarian obsession, but of beauty and inspiration.2 Symbiosis isn’t always a comfortable thing. Perhaps we’re the sharp-toothed things hanging around their refuse piles and hunting… what… for them?

Next week, Nibedita Sen has a new story out with subaquatic horrors and women who sing you to your doom, which we’re calling enough of a thematic link to read immediately because we’re impatient like that. You can find “We Sang You As Ours” in The Dark.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

[1]“Star of David Pin” also gets you pins with every quote David Bowie ever produced using the word “star.” I am not complaining, and my Labyrinth-loving family members will not be complaining either come Hanukkah.

[2]And yes, Jerusalem matches that description all too well.

Did this story win the Newbery Medal?

Excuse me a minute, I need some kitten therapy.

Best doggone dog in Carcosa….

.

Wow, for once I’ve read a new story ahead of the reread here!

I read ‘We Sing You As Ours’ in the latest Dark just a few days ago, and I think it is really good. I’ll be interested to see what you find in it.