Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

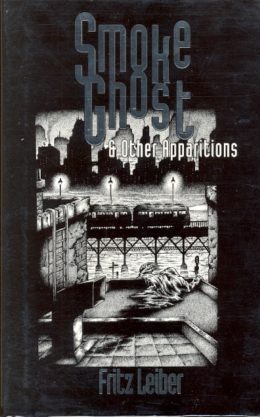

This week, we’re reading Fritz Leiber’s “Smoke Ghost,” first published in the October 1941 issue of Unknown Worlds. Spoilers ahead.

But he always saw it around dusk, either in the smoky half-light, or tinged with red by the flat rays of a dirty sunset, or covered by ghostly wind-blown white sheets of rain-splash, or patched with blackish snow; and it seemed unusually bleak and suggestive, almost beautifully ugly, though in no sense picturesque; dreary, but meaningful.

Summary

Miss Millick is worried about Catesby Wran, her boss at the advertising agency. He keeps making the strangest remarks while she takes dictation, like this morning when he suddenly asked if she’d ever seen a ghost. Oh, not a misty white groaning one, too old-fashioned. No, a modern ghost “with the soot of factories on its face and the pounding of machinery in its soul.” A “vitalized projection” of the world, reflecting all “the tangled, sordid, vicious things.”

Miss Millick sometimes daydreams about Mr. Wran, though she knows he’s married with a young child—not that her daydreams are very exciting. Yet she wonders if he was looking for sympathy when he asked how one could propitiate such a ghost: by sacrifice, worship, simple fear? Being immaterial, the ghost couldn’t hurt you directly, but what if it could get control of a suitably vacuous mind? Couldn’t it then hurt whomever it wanted?

She laughed nervously, then tried to make a joke about the grimy dust on Mr. Wran’s desk, how the scrubwomen are neglecting him.

When she’s gone, Catesby rubs soot from his desk and tosses the blackened rag into a drawer on top of several others. He peers out his window, across a panorama of roofs. His trouble must be “that damned mental abnormality cropping up in a new form.” This time it began on the elevated. Every night on the train he notices one particular stretch of roofs: “a dingy, melancholy little world of tar-paper, tarred gravel, and smoky brick… almost beautifully ugly.” For him, this miniature cityscape symbolizes “the frustrated, frightened century in which he lived, the jangled century of hate and heavy industry and total wars.” Lately he’s also noticed something like a filth-stained sack. It keeps showing up closer to the train tracks, with a bulge that resembles a misshapen head.

Buy the Book

The Survival of Molly Southborne

Last night he saw the thing at the edge of the nearest roof, lifting a “sodden, distorted face of sacking and coal dust.” But he’s made an appointment with a psychiatrist, someone who’ll convince Catesby he merely has a bad case of nerves. Even a diagnosis of mild psychosis would be better than believing what he sees now, on the roof across from his office window: the sooty thing rolling into the shadow of a water tank.

Dr. Trevethick asks Catesby to describe the childhood events he thinks might predispose him to nervous ailments. Catesby obliges. From three to nine years old, he was “a sensory prodigy,” supposedly able to see through walls, to fence blindfolded, to find buried things and read thoughts. His mother “exhibited” him. She also urged him to communicate with spirits, disappointed when he never could. Two young psychologists eventually tested him, were convinced of his clairvoyance, but when they tried to demonstrate his abilities before the university faculty, Catesby couldn’t perform. What had been transparent went opaque, and has stayed that way ever since.

Unburdening long-repressed memories relieves Catesby; he’s even determined to tell Trevethick the whole truth when the psychiatrist inevitably asks whether he’s again seeing things. But then the psychiatrist springs to the window. He quickly returns to his chair, grasping for professional calm. He saw someone outside, a Peeping Tom, but the man’s gone. Whoever, whatever he was, his face was “dead-black.” Catesby sees smudges on the window glass.

He leaves Trevethick’s office convinced that “the bodiless existed and moved according to its own obscure laws and unpredictable impulses.” Afraid to endanger his family, he returns to his darkened office. The precaution fails—his wife calls. Their son Ronny claims to have seen a “black man” outside his window. Catesby rushes to summon the elevator.

In the shaft, three floors down, he sees the thing. He retreats to his office. Minutes later, the locked door opens. Miss Millick comes in. She meant to do some extra typing, but wait, is Mr. Wran sick? He looks it—let her help, get him something from her purse.

As Catesby watches her bend the heavy prongs securing her bag like tinfoil, he remembers his earlier speculation that a modern ghost might gain material agency via possession. He runs from Miss Millick, ending up on the roof. The Millick-thing pursues him, tittering with moronic playfulness: Why, they’re all alone now, she might push him off.

Catesby drops to his knees. In “the lucidity of terror,” he prays. He recognizes the thing as a god, supreme over this city and all others. “In smoke and soot and flame” he’ll worship it forever! The thing seems pleased; then Miss Millick goes pale, nearly faints, and seems herself again. She can’t remember how they got to the roof. She frets about a “big black smudge” on Catesby’s forehead.

He reassures her she had a transient spell and ushers her out of the building. Later, on the empty elevated, he wonders how long the thing will leave him alone. Instinct suggests he’s satisfied it for now, but what will it want when it comes again? To protect himself and his family, he must stay careful and tight-lipped.

How many other people may be doing the same?

The train passes that stretch of roofs where it all started. Now they seem “very ordinary, as if what made them impressive had gone away for a while.”

What’s Cyclopean: “Vacuous” appears to be the word of the day, describing people who might be more susceptible to the ghost’s influence. “Titter” also makes an appearance, never a good sign.

The Degenerate Dutch: Several people mistake the smoke ghost for a “negro,” or maybe for a white man in blackface.

Mythos Making: No elder gods this week, just an entity uncannily good at reflecting the apocalyptic horrors of the 20th century.

Libronomicon: The only books this week are references on shorthand, useful for Miss Millick under most circumstances but woefully inadequate to her current predicament.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Wran at first blames the smoke ghost on “that damned mental abnormality.” Going to a psychiatrist does in fact help, in that it proves that others can see what he’s seeing. Though perhaps “help” is the wrong word, since he’d rather be hallucinating.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

After two weeks of life’s-blood sacrifices, forced and willing, the first thing that strikes me about “Smoke Ghost” is how little the titular spirit ultimately demands. What’s a few words, compared with floating dead in the vacuum of a god’s orbit, or an antler to the throat? And yet, the story loses no creep by the pettiness of the demand. Perhaps even the reverse.

And maybe the sacrifice isn’t so small, at that. For Wran, the smoke ghost is born out of, or bears, everything that’s dreadful about his century, “the eternal vitality of cruelty and ignorance and greed.” It’s October 1941; there will be greater sacrifices. What difference does it make when one man bows to “the inevitability of hate and war,” and promises that it has “supreme power over man and his animals and his machines”?

What happens if a thousand men do?

Leiber seems to have had an almost kinesthetic sense for World War II. We’ve previously covered “The Dreams of Albert Moreland,” written just before the war’s end. Now we have a piece coming out two months before the US enters the war, though it’s hard to tell whether it presages that change, or simply expresses the frustration of someone aware that fascism is rising and that the people around him are doing little about it. A year later he’ll be working as an aircraft inspector for the war effort. Here, he’s creating a presence that embodies all the horror of apathy and despair and undirected anger.

I read: “The quick, daily glance into the half darkness became an integral part of his life,” and thought: Oh, Twitter.

So does the smoke ghost appear for Wran because of his sensitivities, and then to people around him by a sort of contagion? Or does it appear to anyone who can’t resist that glance into the darkness? It seems new to the doctor, and to his kid. On the other hand, it seems like a creature that draws power from pervasiveness. If it likes people despairing before it, promising worship and respect for its power, it can hardly be satisfied with occasional bows from former child psychics.

And it’s almost appealing, isn’t it, to blame the rottenness of the world on spirits? Or to personify that rottenness as something that can be met and fought?

Then there’s Miss Millick, whom it actually possesses. I feel bad for her. Dismissed as “vacuous,” she seems rather sympathetic and a bit too caught up in her time’s scripts for how a secretary is supposed to respond to her boss. And Wran is a bit of a dick to her, monologuing about his fears and then dismissing them as soon as she responds.

On a different note, am I stretching to see some influence here on a couple of movies a few decades later? Ghosts more shaped by the modern world than by ancient tradition, inconveniently possessed secretaries… that sounds like a problem that could come up more than once. And when it does, who you gonna call?

Anne’s Commentary

What are the faces of twentieth-century humanity? According to Catesby Wran, they include:

“… the hungry anxiety of the unemployed, the neurotic restlessness of the person without purpose, the jerky tension of the high-pressure metropolitan worker, the uneasy resentment of the striker, the callous opportunism of the scab, the aggressive whine of the panhandler, the inhibited terror of the bombed civilian…”

Aw, come on, Catesby. Are we moderns really worse off—and deservedly so—than earlier people? Isn’t every age a distant mirror of our own, as Barbara Tuchman put it in her so-named history comparing the twentieth century to the fourteenth? Alternatively, is Yeats right that we’re in a steeper spiral or widening gyre of screwing up:

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned…

Sticking with poets of doom, Eliot promised to show us “fear in a handful of dust,” and we could interpret that dust to include industrial toxins, pesticide residue, weaponized pathogens, nuclear fallout, killer nanites—or simply Leiber’s soot, that year-round urban skyfall. Soot is the pigment blackening his ghost’s face; soot is an apt metaphor for the layers of anxiety, boredom, resentment, callousness, greed, aggression and terror he sees degrading human nature to the point that we need to make new ghosts in our own image. Get rid of the clean white of rural mists. Chuck quaintly eerie graveyards for junk-heaps. Goodbye piteous moans, hello imbecile muttering. We are apes, not angels, so let our spirits reflect that! Our Holy Spirit, too, third part of the Christian God. Or, hell, any god. Forget the ghosts altogether, because that’s what Leiber does by the end of this week’s story. His smoke-entity goes big-time, right for deification.

Last week Premee Mohamed gave us two sets of deities: a Mythosian terror and some (usually) benign local elementals. I accepted both as legitimate gods, at least effectual ones. I also saw both as beings unrelated to humanity, not our creators or creations. That, I think, is Lovecraft’s overarching credo, with the possible amendment that none of the Outer Gods or Great Old Ones or Elder Things deliberately created Homo sapiens. Nor are the Outer Gods, etc., figments of fevered Homo sapiens imagination. They are real. Only too real. Unlike the thoroughly human concept of bonafide divine gods.

Is that “cosmic-scale” reality the scariest thing possible? Or does Leiber up the stakes to scarier-scariest by implicitly asking the question Who made whom? I think so. I think, too, that he gives the totally-scarier-scariest answer of Why, of course it’s Catesby who makes the Soot-faced God. Maybe for sanity’s sake, we could pretend Soot-faced God is all in Catesby’s self-admittedly weird head. But then why does Miss Millick see the soot it leaves on Catesby’s desk? Why does Trevethick see the thing itself, and poor little Ronny outside his window at home? What possesses poor Miss Millick and borrows her titter to such chilling effect?

Why should ordinary old advertising exec Catesby be the one to create a god? I’m sure there’s a Mad Men joke in there somewhere—hell, who better to create gods than those who have elevated the likes of Pepsi and Palmolive to cultural icons? Never mind, because Catesby isn’t ordinary. He was a sensory prodigy in childhood. Clairvoyant, telepathically receptive. He could see things others missed. He’s also particularly sensitive (like our poets of doom above) to the specific ills of modernity and the “eternal vitality of cruelty and ignorance and greed” that underlies them. Why are these things “necessary parts of the picture?” Epiphany strikes when he accepts that the smoke ghost is real: Beyond the material world the “bodiless” exists. It’s a force with “its own obscure laws… unpredictable impulses.” He’s always felt it. As the “cruelty and ignorance and greed” intensify around him, his psychic talent reawakens and perceives the antagonistic force as a sentient sack of garbage, filth mimicking humanity, shambling and idiotic but inescapable.

Because it might as well be a god, it must BE a god. It must be CATESBY’s god, and he by virtue of giving it form must become its worshipper and servant. It can be propitiated no other way.

But at least it can be propitiated. Staved off from killing its visualizer (the ad man!) until the next time he visualizes it.

Yeah, then what?

Oh! And re-reading “Smoke Ghost,” I’ve been so strongly struck by how strongly T. E. D. Klein’s “Nadelman’s God” resonates with it! Might even be considered as an expansive riff on Leiber’s tale?

Am I subtly hinting to Ruthanna that we should look at “Nadelman’s” sometime soon?

Nah, I’m never subtle.

But apparently we can’t have “Nadelman’s God” for next week as there’s no e-book version—we’ll have to order up some dead trees first. Looking for more immediately accessible urban deities, though, I find David Liss’s “The Doors That Never Close and the Doors That Are Always Open” in Gods of H.P. Lovecraft.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.