Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

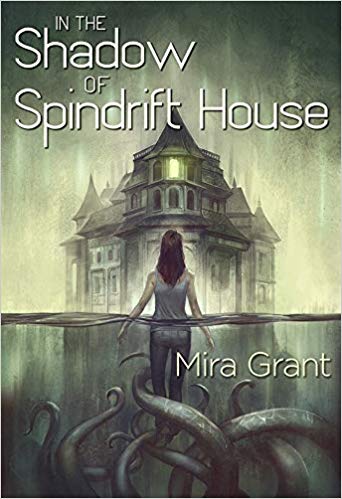

This week, we’re reading Mira Grant’s In the Shadow of Spindrift House, released just this summer as a standalone novella from Subterranean Press. Spoilers ahead, really a lot of spoilers, go read the thing first. We’ll wait.

“Humanity has sacrificed so much on the altar of geometry, sacrificing eons untold to the mathematical aberration of the straight line, the perfect angle. Perhaps one day, they will see the error of their ways.”

Nature is made of curves and spirals, “an interconnected web of compatible shapes.” Only three things truly approach the straight line and sharp angle: lifeless crystals, mindless viruses, and the works of deluded humanity. Nature rages at mankind’s betrayal but realizes mankind’s time will “run fast and hot and short,” unlike that of other sapient species whose palaces “rise in sweet organic spirals.”

Consider Port Mercy, Maine, a fishing town half-reclaimed by the sea. Enshrined above it is Spindrift House, after more than 150 years “still straight and tall and proud, an architectural oddity rendered regal by the slow dissolve of all below it.” Locals agree the house is haunted, but their stories vary. Was it built by a rich fisherman whose bride threw herself from the widow’s walk when the sea claimed him? Or was its builder driven by the creakings of his imperfectly constructed manse to throw himself from the widow’s walk? Or did a rich widow build it, taking obsessive interest in every detail, only to throw herself laughing from the you-know-what the day the house was completed? What’s certain is that the house’s ghosts are old and unforgiving. What’s true is that “the widow’s walk waits; the spiders sigh; and Spindrift House is calling its children home.”

Meet the Answer Squad, a teen detective club whose members have graduated to the irksome demands of young adulthood. Our narrator is Harlowe Upton-Jones, bespectacled brain of the outfit. Mystery is her life—no wonder, given that her parents were killed by a still-unidentified cult. Her paternal grandparents became reluctant guardians; she found her true home with foster brother Kevin and his mom. Anxious but intrepid Kevin makes the Squad’s “messes” worse until the answers show up. Addison Tanaka charges in to “beat down” obstacles, while her twin brother Andy cleans things up.

Harlowe’s loved Addison since they met as kids. Now Addison, armed with charm and elite martial arts skills, is ready for a real career. Andy will follow Addison. Kevin would prefer to pursue mysteries but could content himself with the family farm and his beloved chickens. How’s Harlowe to keep her sleuthing family together?

Her plan involves one of mystery’s “white whales”: Spindrift House. Three families vie for the place: the Pickwells, Latours, and Uptons. They’ll pay 3.5 million dollars to whoever can stay in the house long enough to determine the rightful owner. With the Uptons in contention for Spindrift House, perhaps it holds answers to Harlowe’s personal mystery, but it’s that huge payoff that sells the Squad on one last (or not) job.

In Port Mercy, Harlowe’s repulsed by the gaunt Pickwell representative and sharp-toothed Latour. On the other hand, she’s viscerally drawn to the ocean. The Squad has one week in Spindrift House, and can’t leave without forfeiting the reward.

Inside, a pervasive fungal miasma oppresses all but Harlowe. She smells only homey sweetness, but keeps zoning out and nearly fainting. Also disturbing are indications that the last tenant decamped suddenly, abandoning all possessions, and the spidery attic that seems too big for the house. There they find photos of a woman who looks eerily like Harlowe.

That night Harlowe dreams of Violet Upton, who would proudly occupy Spindrift House until she passed to “the dark and dreadful depths where she would one day be made glorious.” Violet guards certain papers that ensure the Upton’s rights. Harlowe wakes in the kitchen, where she’s sleep-opened a secret pantry door with stairs leading down.

More weirdness: her lifelong myopia’s gone, her vision perfect. A voice in her head urges her to make Spindrift House her home, even as she intuits the Squad better run for their lives. Instead they descend to a cellar housing a locked roll-top desk. What likelier repository for lost deeds? They carry the desk to the kitchen, but Andy falls on the stairs. The question of whether they should rush him to hospital, reward be damned, is moot when he wakes seemingly fine. However, the vibrant intelligence Harlowe sees in his eyes is no longer Andy’s, and she faints.

When she revives, Kevin presses her to leave Spindrift House with him. Andy’s gone wrong, Addison’s denying it, and some mysteries aren’t meant to be solved. Harlowe confronts the ancestral ghost (and unlabeled Deep One) occupying Andy’s corpse, a hermit crab wearing an abandoned shell. He tells her she’s Violet Upton’s great-granddaughter. Harlowe’s mother tried to keep Harlowe from her family destiny—that’s why mom had to die, along with her landbound husband. But now Harlowe’s home.

Not-Andy embraces Harlowe, and Spindrift House itself possesses her body, trapping her inside, a helpless observer. It carries her to the attic, where Addison sorts documents. Addison realizes this isn’t Harlowe, because whatever’s looking through her eyes has no hint of Harlowe’s unrequited love. Trapped, Harlowe watches Addison pound on her possessed body. She watches that unwounded body hurl Addison from the widow’s walk to break on the clifftop below.

Released, Harlowe opens the desk from the secret cellar. The ledger inside, Violet Upton’s, explains the tortuous web of bargains among Uptons, Pickwells and Latours that now makes Harlowe, the last Upton, Spindrift House’s rightful owner. The house comes to her in Andy’s corpse, and she argues it into letting Kevin go with the reward money.

Andy and Addison get only unmarked graves in the family boneyard. From the sea’s song, Harlowe gleans the name of her true lord, Dagon. She’ll guard Spindrift House until she Changes; more, she’ll find more of her lost cousins, and bring them home.

After all, mystery’s what she does.

What’s Cyclopean: Spindrift House “looms, four stories of artifice and artistry, with gables and filigreed porch covers warring for space with window nooks and the aforementioned widow’s walk, which circles the whole of the roof, as if the sailors lost at sea might come from the tangled hillsides behind the house itself.” As well they might.

The Degenerate Dutch: The three families make up for their lack of any overt traditional prejudices by really hating each other.

Mythos Making: Ancient families breeding with creatures of the deep ocean, horrific angles… and a universe that finds humanity an irritant at best. Sound familiar?

Libronomicon: Violet Upton’s diary provides many answers that readers may not want to know.

Madness Takes Its Toll: One of the stories about Spindrift House’s creation suggests that the house creaking in the wind drove the builder mad.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

It’s an open question how Lovecraft himself actually felt about the ending of “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” or how he expected his readers to feel. On the one hand, our narrator spends most of the story hearing nothing but ill about the Deep Ones—and if that stuff is true, would you really want to grow suddenly delighted by your kinship with people who hide shoggothim in the sewers? On the other hand, dwelling beneath the waves in wonder and glory does sound pretty awesome. And who’re you going to believe about the true nature of reality: the town drunk with a badly written accent, or the grandmother you meet in dreams?

A good portion of us have come down squarely on the side of Team Wonder and Glory. I’ve written a couple of books myself in which that’s a pretty damn happy ending, and it’s more the beginning of the story that should inspire dread. In In the Shadow of Spindrift House, Seanan McGuire (in creepy Mira Grant mode) asks instead: what would it take to make the ending of “Shadow Over Innsmouth” genuinely horrifying? And comes up with perhaps the world’s least predictable answer: make it an unmarked Scooby Doo crossover.

I’m delighted by this answer, even as I realize that I’m glossing over a huge portion of the horror by describing it this way, because I’m still bouncing about how clever it is. But the actual, deeper answer is: set newfound blood family against longstanding found family. Lovecraft’s narrator loses nothing but his ill-considered humanity. Harlowe loses everything. Her “Shadow” is a story about genetic relations who kill your parents, trap you as well, destroy the found family who saved you, forcibly take over your loyalties, and then get you to do the same to others. Somehow, that makes immortality beneath the waves sound less appealing.

She’s also playing with Lovecraftian ideas about what it means for something to be unnatural. The house explicitly violates natural law—but in a way shared by many human houses, built of Long’s evil angles amid a nature that delights in curves. “Humanity is an aberration, an affront upon all that is right and true and holy.” For most Mythos fiction we define what it means to be natural, even as the stories admit that we’re trivial in the grand scheme of the universe. Narratively, though, the unnamable is shaped by what we’re capable of naming, abomination by how abominable we find it. In Spindrift House, we live on the edge of horror because everything else—“the other thinking peoples of the world, whose time is slow and cool and long”—is horrified by us. And yet still wants us to “come home.”

So what happens when a house of angles becomes a tool of those other peoples?

We’ve previously covered two Seanan McGuire stories and one Mira Grant. There’s a lot of aquatic attraction-repulsion in there, and a lot of family of all kinds. There are more overtly described Deep Ones and more overtly mortal dangers, as well as sacrificial ball games and face-eating mermaids. Spindrift House honestly terrifies me more than either the mermaids or the unethical human subjects experimentation (and it takes a lot to terrify me more than unethical human subjects experimentation). Lots of things can kill you, and lots of things can kill the people you love, but not many things can make you quite that complicit.

Anne’s Commentary

Confession: The original Scooby-Doo animated series really annoyed me. Not only do I dislike talking dogs of any breed, I hate it when the paranormal elements of a story are explained away as hoaxes, which is what happened to every monster-of-the-week Fred, Daphne, Velma, Shaggy and the Scoobs investigated. I was always praying they’d try to pull the mask off a creature only to find there was no mask (shades of the King in Yellow!) Or better yet, that what was under the mask was even worse than the mask itself. And then it would gobble down the amateur detectives like so many Scooby snacks.

I have the same problem with William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki stories, in which the supernatural is sometimes revealed to be only too criminally mundane. At least Carnacki goes up against real ghosts from time to time, and even Hell-Hogs. Better still: Though Buffy and friends may refer to themselves as the Scooby Gang, when they run across vampires or werewolves or demons, they are GENUINE vampires or werewolves or demons, thank you very much.

Mira Grant gives us a bunch of teen sleuths who recall the Scooby-Dooers, with some delightful identity switches. While Harlowe slips comfortably into Velma’s research-nerd shoes, beefy leader Fred becomes deceptively lissome Addison. The chronically-imperilled Daphne becomes frequently-abducted Andy. Scaredy-cat slacker Shaggy becomes stoner Kevin, who may have anxiety issues but who’s neither a coward nor a fool. As for the dog, thankfully there’s only that superannuated Petunia who lives to worship Kevin. And fart. She doesn’t talk, and she doesn’t accompany our heroes on their adventures. Not that I’m opposed to dogs as more active characters. In fact, Grant writes one of my favorites, Dr. Shannon Abbey’s Joe from the Newsflesh series. Joe is cool because he acts like a dog, albeit one who can kick zombie ass without succumbing to undead viruses. And he speaks only with his tail and his soulful eyes. I don’t remember if he farts in particular.

Enough cozy canine chatter. The important thing about Spindrift House is that though its detectives have unmasked fake monsters in the past, this time they are up against the REAL THINGS. Are they ever, and the worst thing? The Answer Squader who leads them to Spindrift House is a monster herself, well, if you consider Deep Ones monsters. Harlowe doesn’t, once she yields to the sea’s glamor and accepts her glorious heritage. From terror and revulsion to exaltation and proselytizing appears to be a common transition for Deep One hybrids. Which I get, because the flexibility of an amphibious lifestyle? Splendid deep sea condos? Eternal life? I’d be in, too, though I wouldn’t want to pay the high price Harlowe does in friends and beloved. Andy’s lethal fall down the cellar stairs may have been a bona fide accident, but he wouldn’t have fallen down those stairs if Harlowe hadn’t lured Addison (hence also Andy) to their vicinity. It may be the spirit of Spindrift House that hurls Addison to her death, but Harlowe is united with the House in perceiving Addison as essentially selfish and capable of exploiting a love she’ll never return. Kevin escapes but loses his “sister,” as Harlowe loses her “brother,” the deepest relationship of her life.

Spindrift House suffers, I think, from the shorter-form-that-needs-to-be-a-novel syndrome, but it’s far from a fatal case. The novella achieves a powerful poignancy perhaps best captured in Harlowe’s closing reflection that “The sea sang in the night, and my heart sang with it, and oh, I am damned, and oh, I am finally home.”

In that poignancy it strongly recalls to me Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House. Parallels between Hill House and Spindrift House seem intentional. Both works have omniscient openings stating abstract premises to be illustrated: Jackson’s “No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality,” Grant’s “Nature is a force of curves and spirals…” Both feature houses of curious solidity and sensible straightness which are nevertheless hideously, terrifyingly wrong in their dimensions—sick from the start and to the heart. Some of the central characters are comparable: Harlowe and Eleanor, the wounded ones seeking—and called—home; Addison and Theodora the brilliant, self-centered, manipulative love interests; Addison and Luke, possibly ditto Addison and Theo. Andy and Kevin may share the role of Dr. Montague as the occult-attracted but sensible moral centers of the ghost-hunting parties.

Hill House with Deep Ones? What a concept! Spindrift House also begs, intriguingly, to be compared to Seanan McGuire’s “Down, Deep Down, Below the Waves.” What’s a right-minded proto-Deep One to do but share the joy by seeking out other proto-Deep Ones, am I right? Even Howard’s Innsmouth narrator went after his sanitarium-languishing cousin.

Families have to stick together, which may be easier when they’re semi-batrachian.

Next week, the stars are right for a vacation: we’re taking a break for Necronomicon and various end-of-summer obligations. We’ll have a con report when we get back, and after that… actually, we haven’t decided yet. Probably some delightfully creepy new discovery from Necronomicon. Stay tuned, and we’ll see you on the other side…

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

TEEN DETECTIVE CLUB!!!!! (runs off to buy)

I’m going to have to stick up for the original ‘Scooby Doo’ series- the lesson is that investigation and research are more powerful than fear and complacency. There are monsters out there, but they are human, and their motives are usual banal, like greed or revenge. ‘Scooby Doo’ is a standout, how many other kids’ shows pushed for skepticism and empiricism?

Sure, the oldest and strongest emotion might be fear, and the oldest and strongest fear might be fear of the unknown, but intellect and curiosity can win over fear. As much as I dig Cosmic Horror, I am on Team Discovery all the way.

I’d love to read this, but Subterranean won’t sell ebooks to Canadians.

This reminds me of a very similar book, Meddling Kids by Edgar Cantero. A teen detective gang unmasks yet another monster in a haunted mansion in the 70s. But by the 90s the case has still stuck with them all in various ways, with one member locked up in, that’s right, the Asylum at Arkham.

It’s a bit more lighthearted than this one, but still fantastic and absolutely Lovecraftian.

Here’s to team Glory and Wonder! I hope we see another Innsmouth Legacy book someday so we can all get a little closer to Aphra’s happy ending.

Teen detectives immediately send my mind to John Alison’s Bad Machinery. Tackleford has its share of Lovecraftian horrors, but I don’t think the kids get involved with any of those; just more mundane supernatural things once in a while. Can’t recall if they interact with Desmond Fishman or if he’s just in some of the side stories.

@3: Not so much “won’t” as “can’t”. They’re a small press and international distribution rights can be expensive. Canada is a little surprising, but I didn’t find it odd that I couldn’t get it here in Germany.

I like this very much

I’m sorry, but I did miss the dog.

A second mention for Meddling Kids. Though I wouldn’t call the book light-hearted; that the responsibilities of adult life hit that detective squad harder than anything the Lovecraftian horrors manage is not necessarily a plus…

Scooby-Doo always annoyed me as a kid, too. I loved ghost stories, and I wanted the monsters to be real.

OK. I’m sold.

*throws octopus plushie at the wall several times.* Damn it! Seanan McGuire is still finding new ways to torment me with things I can’t have. This time rhe character doesn’t just (realize she’s fated to) become a marine humanoid; her visual impairment gets cured. My severe lifelong visual impairment, including but not limited to myopia, is incurable (being rare and not degenerative, it’s not a priority for opthamological R & D). I would…not sacrifice my loved ones for a cure, but might be willing to pay a high price of some other kind even if it doesn’t involve becoming marine. Among many other benefits, I would be better able to explore the oceans, to the degree that humans can do so, if I could see well.

As I said last time it was relevant: “If we were meant to live in boxes, we would have corners.” — biomimicry expert Jay Harmon

I didn’t know Scooby-Doo had quite as much focus on hoaxes. I never watched much of it. I did watch the film “Scooby-Doo and the Ghoul School” and went stark raving blissed-out because I had seldom, if ever, previously encountered female monster children outside my own story-headcanon-imaginings. Those were defintely supernatural beings, albeit kind-hearted ones.

I’d love to read it, but I’m too darn poor! ARRRRRrGHggggg!

Although I did wipe out the Scooby-Doo gang in an unpublished story

As a bookseller, I’m hoping that this and the other recent McGuire/Grant Subterranean Press titles will be collected and reprinted in another omnibus soon. This one’s already out of stock… SubPress stuff goes out of print too fast, and they aren’t very open to small “indy” stores trying to set up direct wholesale accounts for pre-orders (e.g.: too-high minimum quantities to get wholesale pricing). :

Hey. Hey. Shoggothim should NOT be hidden in sewers. They should be carefully propitiated with animal sacrifice so they aren’t hungry and said many nice things about so that they feel friendly and happy and don’t randomly impersonate your deity for kicks and giggles and tell your high priest to do weird stuff like paint his big toes with goats blood or whatever because monkeys are a barrel of laughs.

heh. I think I figured out how to explain the parts where god walks and eats for no apparent reason.

I found a Litany for Aphra’s Mom.

https://poets.org/poem/and-death-shall-have-no-dominion

Tegan @@@@@ 15: Thank you for the poem! Thomas has his own sort of deepness and weirdness.

As usual with Seanan/Mira’s work, I loved this. The repeated mentions of spirals made me wonder if Grant has read Junji Ito’s Uzumaki.

I did wonder about what exactly the spirit that possesses Andy is. Is it a living Deep One using something like astral projection to take over his body? Or a Deep One ghost?

If you’re taking recommendations, I recently read a story called “Settler’s Wall” that was very good. It was published in Startling Mystery Stories way back in the Fall 1968 issue and is available via the Internet Archive.

Heey. wait. About the Lovecraftian mound dwellers. If in your books, the deep ones are analogous to the jewish community, could they be analogous to the Hasids?

I mean, canonically, both groups do worship Cthulhu.

I’m sorry about trying to find extra possible meanings of your books. Apparently my brain spends too much time making connections. Ppl would usually rather it slowed down.

I honestly think of the K’n-yan as more like modern high-tech high-privilege cultures, with magic taking the place of money and technology as an impetus for the belief that if you can do the thing then you should do the thing. Not that Lovecraft and Bishop were likely thinking about Silicon Valley Fair Folk when they wrote that story.

Ah, the internet. Undermining the death of the author since the days of Usenet. Feel free to ignore me and speculate away…

Oh no! I definitely want your input! I’m writing a story where Puck shows up and tells a lost K’n-yan he’ll lead her back to fairy land. I’m just trying to figure out where to go with it.

I’m… I’m not actually terribly knowledgeable about Jewish culture. I just know I have failed to pick up a ridiculous number of Jewish lesbians after mentioning my mom used to be obsessed with Chaim Potok (before she became a Christian). Isn’t he an ex hasid, or something?

Quite a switch I suppose. From ‘a sexy evil German’ to ‘your annoying cousin’. I just hadn’t picked up on the annoying cousin part.

About the K’n-Yan, I don’t know. If they were that unfettered, wouldn’t they be ruing the planet? I know Lovecraft was paranoid af and a member of the ruling class, but why exactly do they stay sealed underground all the time? Like- like in bunkers kind of?

And didn’t Cthulhu specifically bring them along from where ever?

If you assume Cthulhu is not sleeping, but imprisoned, suffering some sort of cosmic defeat, they could just be loyalists.

Here’s my archetype. what do you think?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oxv1Q8YZdA4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G9ywUzK1wIs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NP6Ob-MKjBQ

@19: Yeah, Seanan McGuire is the one who writes about Silicon Valley Fair Folk. :-p

@20: I’m personally acquainted with with a number of Jewish lesbians and Jewish bi women.

19- YES. Yes. I definitely think a high privilege culture is involved somewhere along the line. I’m just not sure it’s the K’n-yan. (no offense to S.M.)

have you seen this? https://www.theoi.com/Gigante/Typhoeus.html

dude looks a f-ton like Cthulhu

The enemy of the greek gods- typhon. He was their enemy- defeated and imprisoned ” somewhere”. But, if we’re re-seeing things, the greek gods were rapey sadistic murdering creeps- no matter how many cutsy cartoon fables are devoted to making them look better.

In my spare time, my hobby is trying to correlate pre axilial religious mythologies into a single narrative. those are what gave rise to all the civilizations of earth. Like- if we started over, but together this time, would it be easier for humans to see eachother as human?

I’ve been finding Lovecraft makes a nice solvent.

Ah! Have you ever read this? https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/35926246-the-asylum-for-wayward-victorian-girls

towards the end the inmates take over the asylum and make it their own.

21-aaaah introduce me to them! I’m still trying to get my mummy to love me!

oh wait.

Here.

“…John Willis went into the mound region after horse-thieves and came out with a wild yarn of nocturnal cavalry horses in the air between great armies of invisible spectres—battles that involved the rush of hooves and feet, the thud of blows, the clank of metal on metal, the muffled cries of warriors, and the fall of human and equine bodies. These things happened by moonlight, and frightened his horse as well as himself. The sounds persisted an hour at a time; vivid, but subdued as if brought from a distance by a wind, and unaccompanied by any glimpse of the armies themselves. Later on Willis learned that the seat of the sounds was a notoriously haunted spot, shunned by settlers and Indians alike. Many had seen, or half seen, the warring horsemen in the sky, and had furnished dim, ambiguous descriptions. The settlers described the ghostly fighters as Indians, though of no familiar tribe, and having the most singular costumes and weapons. They even went so far as to say that they could not be sure the horses were really horses.

The Indians, on the other hand, did not seem to claim the spectres as kinsfolk. They referred to them as “those people”, “the old people”, or “they who dwell below”, and appeared to hold them in too great a frightened veneration to talk much about them.”

The Indians, on the other hand, did not seem to claim the spectres as kinsfolk. They referred to them as “those people”, “the old people”, or “they who dwell below”, and appeared to hold them in too great a frightened veneration to talk much about them.”

Who were they fighting with? Why would Cthulhu have warriors on earth, and who or what would they be fighting? Why aren’t they fighting more… um… substantially than just defending their mound entrance?

They’re waiting for him, aren’t they.

To get free.

Sopie @@@@@ 20: I love the idea of Puck playing with a K’n-yan. And vice versa. If your main job is getting between Oberon and Titania when they’re fighting, I suspect you’d be up for it.

Chaim Potok… like, I wouldn’t call him an active turn-off, but he’s extremely core canon for religious classes. It’s probably a bit like bringing up Dickens if someone’s just mentioned that they’re British? This is all based on extremely vague memories of The Chosen, because no one in my family is particularly obsessed with him…

And whoa, that is the most K’n-yan take on Alice in Wonderland that I’ve previously failed to imagine! I’m disturbed, and I love it.

I seem to recall that the K’n-yan were terrified of what would happen if they came above-ground, having grown terrified of the rest of the world. But I could at this point have written my own head-canons into the original.

Dickens.

huh.

https://www.wattpad.com/story/201722046-yig

@@@@@ 24 She’s never said she’s Jewish though. I don’t know if I would be ruining her life somehow by saying so.

Otherwise I would in a minute.

I had a friend in college. His grandfather and great grandmother escape europe just before it happened. Like- there was an incident where the mother shut the son in a closet and told him not to come out for an hour, no matter what, and went off with a Nazi officer. The grandfather was an alcoholic as an adult, and my friend was a little bit Dionysian too.

In a good way :)

He was the most curious, optimistic person I’ve ever met. He died suddenly a few years ago. I think I never got over it.

One time, one of our friends sat and played this song by lamplight on a classroom piano. He sat and listened and his face light up with pleasure. I sat and listened to both. They were both so beautiful.

pppll. I’ll stop bothering you. You do have the most interesting analysis though. And I did mean that about Rashi.

I think this is my thought about Aphra mourning her ‘non eternal’ friends as she makes them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F9kXstb9FF4