In pre-Internet times, it was hard for everyone who didn’t live in an English-speaking country to buy science fiction and fantasy made in the US or in the UK. It was far from impossible, but very often it wasn’t feasible: we had to send letters (yes!—paper ones, mind you) to bookstores, but the whole operation would only be interesting money-wise if we gathered in a four- or five-person group to buy, say, two or three dozen books. And I’m talking about used books, of course. Most of my English-language books during the Eighties and Nineties were acquired this way, including Neuromancer (but that is another story, as the narrator in Conan the Barbarian would say), in the notorious A Change of Hobbit bookstore, in California.

Some of them, however, I borrowed from friends who had been doing pretty much the same, or buying the occasional volume in one of the two bookstores in Rio that carried imported books. One of these friends I’d met in a course on translation—Pedro Ribeiro was an avid reader, as I was, but his interests tended more to the Fantasy side. He introduced me to many interesting writers, such as David Zindell (who remains to this day one of my favorite authors), and, naturally, Gene Wolfe.

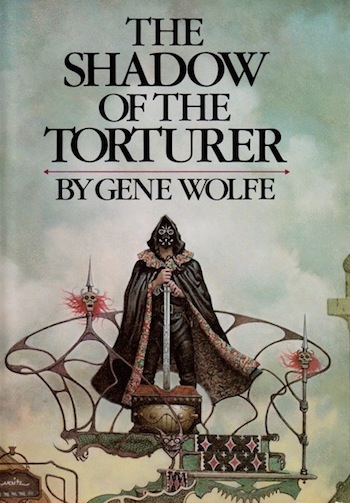

The first thing he said about Wolfe was: “You must read this,” and showed me The Shadow of the Torturer. The cover of the book displayed a man wearing a mask that covered his entire face, except for the eyes. He also wore a hood and a cloak that made me think of Marvel’s Doctor Doom—but a really grim Doctor Doom, not the camp, sometimes even ridiculous antagonist to the Fantastic Four in the comic books. A quick search on the internet tells me that it was the Timescape edition, with cover by Don Maitz (the same artist who provided the cover art for the Pocket Books’ edition of The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories and Other Stories). I’m not quite sure of the year this happened, but it probably was 1986 or 1987. By then, Wolfe had already published the entire four-volume cycle. It was probably in 1986, because the fifth volume, The Urth of the New Sun, was published in 1987, and I remember that Pedro had just told me that a new book in the series was due soon.

I am addicted to reading (as you, Reader, would have probably surmised by now). I can’t read enough. Currently, I’m reading four books: two paperbacks and two e-books. I’m reading faster now, at 53, than at 21. But I always read more than one book at a time, and I’ve always loved reading series. So, the fact that The Shadow… was the first in a tetralogy wasn’t a daunting one. And there was one more thing: Pedro had said, when he lent me the book, “It just looks like fantasy, but it’s in fact science fiction. Far future, Dying world.”

I was sold.

I loved Jack Vance, and by that point I had already read many books by him. The Demon Princes saga and Maske: Thaery were among my favorites. Funny thing was, I had only read one of his Dying World novels. (And to this day, that remains true.) But Vance was a worldbuilder like no one I had ever read. The way he portrayed human societies scattered across the galaxy in a distant future was a delight to read, and stayed with me—I can still remember Kirth Gersen trying to taste a bituminous substance considered a delicacy in one of the worlds he visited, during his search to kill the Demon Princes that ravaged the Mount Pleasant colony and killed his parents.

So I took The Shadow of the Torturer home with me. But I probably started to read it right away, on the bus (it was a forty-minute trip between Pedro’s house and mine).

If I had to describe this first novel of the series to you now without having read it again after so many years, reader, I must confess in all honesty I wouldn’t be able to do it properly. I had only a few scenes set in my mind, after all this time: Severian entering a tower in the shape of a spaceship; his conversations with Thecla, the lady in the lake he finds later; and the roguish duo of Dr. Talos and Baldanders. No more than that.

Naturally, I’m not telling all the truth… I remembered one more thing, no less important than the scenes themselves: the wonder and estrangement I felt upon reading words that just didn’t belong to my personal experience reading in English, thus far. Words like destrier, chatelaine, and armiger, to name a few.

This time, I didn’t have the original editions with me. Having read them all, I had given them back to Pedro, and that was that. I have never thought of buying an edition of the series for myself. Or rather: from time to time I had thought about it, but somehow I never did. I would have loved to buy special editions, such as the recently published de luxe edition by The Folio Society, but not only the price was forbidding, but the edition had sold out in a couple of days.

So, I started reading the series again for the first time since my original immersion…and what a delight it was to give The Shadow of the Torturer another reading. It’s a deceivingly simple narrative; in contrast to many epic Fantasy (or SF) sagas, its volumes are rather slim. The Shadow… is 214 pages long, according to my Kindle edition. And the plot itself is rather simple, and yet so poignant: it’s a first-person account, written (we become aware of it in the very first pages) in the future, when the protagonist, Severian, is old and already the Autarch. So, there is no surprise for us—but Wolfe knows how to keep us interested in how Severian progressed from a young man (a torturer’s apprentice, of all things) to the ruler supreme of Urth—which, of course, we also know that is just a phonetical way to write Earth.

We are in the distant future—so distant that we don’t have a single reference to a past that might be recognizable by us readers. With a single exception, that is: a picture that Severian studies at the pinakhoteken in the Citadel:

The picture he was cleaning showed an armored figure standing in a desolate landscape. It had no weapon, but held a staff bearing a strange, stiff banner. The visor of this figure’s helmet was entirely of gold, without eye slits or ventilation; in its polished surface the deathly desert could be seen in reflection, and nothing more.

He is seeing, of course, an astronaut on the Moon, probably Neil Armstrong. But now the satellite is terraformed, and it looks just like Urth with its green moonlight (a beautiful image as well) and even Severian apparently is not aware of the fact that once the moon was a desolate world.

The future in which Severian lives has somehow reverted to an almost medieval state: customs, clothing, social order—which consists mostly of nobility, plebs, and civil servants who gather in guilds. This last group includes the Seekers for Truth and Penitence, as Severian’s guild is named; in Castle of the Otter, Gene Wolfe himself urges us not to call it the Guild of Torturers, since that isn’t their true name.

Speaking of Otter (what a brilliant idea Wolfe had, by the way—writing a collection of essays whose title referred to the incorrect announcement of the title of the last book in the series, The Citadel of the Autarch, in Locus magazine): there is an impressive trove of criticism available regarding The Book of the New Sun. As always on this rereading, I must remind you, Reader, that these are my personal impressions on Wolfe’s oeuvre, not a critical or academic study. And for my part, I remain deeply impressed, more than thirty years after my first reading.

The first sentence of the novel is as foreboding as the beginnings of other great stories about memory and nostalgia, such as García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Chronicle of a Death Foretold:

“It is possible I had some presentiment of my future.”

Severian has just escaped drowning when the story starts. Along with his mates Roche, Drotte, and Eata, he seeks to enter and cut through the cemetery, in order to return more quickly to their lodgings. And he chooses this point in his life to begin the writing of his memories because the vision of the rusted gate, “with wisps of river fog threading its spikes like the mountain paths” (what a beautiful image), remains is his mind as the symbol of his exile. (The whole series is full of symbols and symbolic moments—such as drowning, a situation that will be repeated a few times in the course of the narrative.)

Instead, they encounter volunteers guarding the necropolis, who don’t let them pass. Severian and his friends manage to deceive them, but they end up in the middle of a small skirmish between these guards and a man called Vodalus, who is someone both admired and feared by them. We don’t know anything about Vodalus, who seem to be a resistance symbol of some kind. Is he a revolutionary? If so, what revolution does he seek to bring? (Echoes of The Devil in a Forest come to mind; could Vodalus be a subtler, more refined version of Wat the Wanderer?) Be that as it may, he is accompanied by a woman with a heart-shaped face, who he calls Thea. In the skirmish that follows, Severian, practically by accident, saves Vodalus’s life. In recompense, Vodalus gives Severian a small coin, which he will keep as a memento.

Later, Severian will return to the Matachin Tower, where the members of the guild live. This tower, now I see, is the same I still remember after all these years, the tower that once had been a spaceship. The description doesn’t give us much first, until almost the end:

Just underground lies the examination room; beneath it, and thus outside the tower proper (for the examination room was the propulsion chamber of the original structure) stretches the labyrinth of the oubliette.

We also are informed of the methods of the guild, which are considered mostly judicial punishment, even though sometimes they go outside this routine—for instance, flaying the leg of the client (as they call their victims) while keeping her conscious. Immediately after this, Severian experiences two encounters that will change his life forever.

The first is with a dog—a mangy, wounded dog whom he calls Triskele. The dog was left for dead, but Severian feels pity and takes him to his room, where he cares for him (hiding from the masters, since torturers, or at least the apprentices, were not allowed to keep animals) until he is out of danger. He uses all the medical expertise he first learned for torturing people into healing the dog. For the first time (at least in this narrative), Severian notices that something has changed:

I knew him for the poor animal he was, and yet I could not let him die because it would have been a breaking of faith with something in myself. I had been a man (if I was truly a man) such a short time; I could not endure to think that I had become a man so different from the boy I had been. I could remember each moment of my past, every vagrant thought and sight, every dream. How could I destroy that past? I held up my hands and tried to look at them—I knew the veins stood out on their backs now. It is when those veins stand out that one is a man.

(Another aside: the impact of this was so great upon my young self that, years later, I would recall this scene and look at the veins finally standing out on the back of my hand, seeing, not without some surprise, that I too was a man.)

One week later, though, Triskele vanishes, and Severian search in vain for him. During the search, he meets a woman called Valeria, in a place full of dials—according to Severian, “old, faceted dials whose multitudinous faces give each a different time,” and so it’s called by her the Atrium of Time. She looks older than him, but to Severian she seems older even than Master Palaemon, “a dweller in forgotten yesterdays.” They talk briefly, and one of the topics is very significant of things to come: Valeria asks Severian if he likes dead languages, and tells him the dials in the Atrium have mottoes, all in Latin (though she doesn’t name the language). She them proceeds to tell him three of these mottoes and furnish also the translations.

Being a speaker of Portuguese, a neo-Latin language, I suspected the translations weren’t very precise, and I searched for their meaning online. The first motto is LUX DEI VITAE VIAM MONSTRAT, which Valeria translates as “The beam of the New Sun lights the way of life.” A more precise translation would be: “The light of God shows the path of life.” That God is considered the New Sun is crucial to the story (usually this title goes to Jesus, but in the Catholic liturgy, Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit are but three aspects of the same thing, all perceived as the same being). Also, as Severian himself will say in another part of the narrative: “It is my nature, my joy and my curse, to forget nothing.” His eidetic memory is a symbol of omniscience, and only the Divine can possess that power.

In my memory, I was quite sure the Atrium of Time would appear again further on in the series, but I really didn’t remember, so I cheated a bit and searched for this information. I found out that it does indeed appear later, but I’m not going to tell you when. Valeria also appears again, and will have an important role in the fourth book, The Citadel of the Autarch; but aside from confirming my memories, I didn’t search for more, for I want to experience the series again while preserving as much sense of wonder as I can.

So the first encounter is in fact two, even though Severian will only understand the significance of meeting Valeria much later. If the encounter with Triskele changes the perception Severian has of himself, the next is going to set things in motion for this newly-rediscovered (newborn?) man.

As an apprentice, he has to fulfill several tasks at the Matachin Tower, including serving meals to the above mentioned “clients.” One of these clients is an exultant, or noble-born person. She is the Chatelaine Thecla, and Severian will meet her for the first time in order to give her a few books she has requested. Severian first visits the archives and talks to Master Ultan of the Curators. Ultan is blind, and he keeps the library dark, which lends a grim aspect to its aisles. The description of the types of books there is a thing of beauty:

We have books whose papers are matted of plants from which spring curious alkaloids, so that the reader, in turning their pages, is taken unaware by bizarre fantasies and chimeric dreams. Books whose pages are not paper at all, but delicate wafers of white jade, ivory, and shell; books too whose leaves are the desiccated leaves of unknown plants. (…) There is a cube of crystal here—though I can no longer tell you where—no larger than the ball of your thumb that contains more books than the library itself does.

(For anyone with an interest in Latin American literature, this is a beautiful homage to Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine writer who penned the marvelous short story “The Library of Babel,” and who became blind in his middle age. Umberto Eco did the same kind of tribute in his novel The Name of the Rose, whose original Italian edition was published in September 1980. The Shadow…. would see publication in May that same year. An elegant convergence, we might say.)

Severian then meets Thecla for the first time, and—even though they shouldn’t—they will become friends of a sort. He will, naturally, fall in love with her.

I’ve already written too much, here, and we have barely reached a third of the story. So I will deliver this narrative and my reactions in installments—not only in terms of the Sun Cycle proper, but splitting the novels when and where needed. If the New Sun novels are slight in number of pages, on the other hand they are so full of ideas, themes, and images that they’re difficult to capture in a relatively brief space, but for the purpose of presenting his books to a new audience (or, again, re-presenting them to returning readers), this must suffice.

I will be waiting for you all, then, on Thursday, September 5th, for the second installment of The Shadow of the Torturer…

Fabio Fernandes started writing in English experimentally in the ‘90s, but only began to publish in this language in 2008, reviewing magazines and books for The Fix, edited by the late lamented Eugie Foster. He’s also written articles and reviews for a number of sites and magazines, including Fantasy Book Critic, Tor.com, The World SF Blog, Strange Horizons, and SF Signal. He’s published short stories in Everyday Weirdness, Kaleidotrope, Perihelion, and the anthologies Steampunk II, The Apex Book of World SF: Vol. 2, Stories for Chip, and POC Destroy Science Fiction. In 2013, Fernandes co-edited with Djibrilal-Ayad the postcolonial original anthology We See a Different Frontier. He’s translated several science fiction and fantasy books from English to Brazilian Portuguese, such as Foundation, 2001, Neuromancer, and Ancillary Justice. In 2018, he translated to English the Brazilian anthology Solarpunk (ed. by Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro) for World Weaver Press. Fabio Fernandes is a graduate of Clarion West, class of 2013.

I first read these books last year. I was blown away by the dreamlike writing. Several nights in a row I was so enthralled by them that I’d reread aloud what I’d read the previous night to my wife while she went to sleep.

It’s very seldom that I reread books but I’m really excited to dive back into this writing with a greater understanding.

Very nice look at the beginning of a great book. (And Maske: Thaery is also one of my favorite Vance novels.) And it really is cool to see the perspective of how you got English-language books in Brazil back then …

To nitpick slightly, the picture of the astronaut would be of Buzz Aldrin. Armstrong was the photographer. (Or I suppose it could be a picture from a later mission, though I’m not sure any fit.) That scene is one I particularly remember — the realization of the true nature of that picture lingers as a special moment in reading that book.

I haven’t reread The Book of the New Sun in a long time. Maybe now is a good time!

But, Fabio, my good fellow, ‘Urth’ is not just a phonetical way to write ‘Earth’, Urth is also the name of the Norse Norn who represented the past.

The true power of Wolfe’s writing is that just about every word is freighted with meaning below the surface.

Love the rereads! I think BotNS is Wolfe’s love letter to ‘The Dying Earth’, and ‘The Dying Earth’ is Vance’s love letter to CAS’ ‘Zothique’.

I too am a Vance fan, and greatly admire this book. Or perhaps I should better say the first several chapters of this book.

I found the early part enthralling, lyrical, and terrifying all at the same time. But by mid-novel, the enchantment had worn off. The plot became mired, the characters stilted, and neither ever quite recovered. And the sequels were not an improvement. I suspect that the series was sold on the strength of those first few incandescent chapters. I kept reading Wolfe, but I have never thought he lived up to his early promise.

@@.-@: My thoughts exactly.

One of my favorite series of all time, and I’m sadly overdue for a reread.

I have to admit that I didn’t pick up on the astronaut picture until I read about it after the fact.

So many things I love about these books, including such delicate touches as replacing sunrise/sunset with “the Urth turned her face towards/away from the sun” and the way that you don’t learn the sky is always star-filled until Severian comments on visiting a place that doesn’t always have stars visible in the sky.

Indeed, @Kirth! I’ll have more to say about the nature of the names in the second part of the review.

Thank you, @ecbatan! I read quite a few articles and interviews and I couldn’t find any particular reference from Wolfe regarding who the astronaut was, but it was probably Buzz Aldrin all right.

@3

Wolfe rather gives this away by referring to Mars as Verthandi and Venus as Skuld, which I thought was pretty clever. He goes further by relating Verthandi’s name as being a renaming, by the first Martian colonists; it was meant to entice further colonists, as it means “present”, which could be taken as what is opposed to the past (which Urthr can be interpreted as representing, and old, worn-out world) and also to refer to “present” as a gift, that is, the gift of a fresh start to history on a new world.

On another note, I went to school with an Ultan. Also a Roche. No Severian, but perhaps that’s just as well.

Wolfe underestimated (as most did, in truth – I would include myself) the detailed evolution of information technology. That cube of crystal – no larger than the ball of one’s thumb, that a harlot might dangle from her ear as an ornament, but which contains more books than any library – is real; we even call it a thumb drive. And its functional components are tinier than you might expect.

Mr. Million in The Fifth Head of Cerberus is another example. He points out that he is actually Mr. Milliard, a simulation of a thousand million neurons. When he goes outside, he is constituted in a caterpillar-like train of computational modules. Nowadays a simulation of a thousand million neurons is not so much larger than a thousand million neurons themselves. (It is a little larger, it takes much more energy, and it runs faster. It has not yet been programmed into life, but soon it will be.)

That said, Wolfe accepted that we will share our future with artificial beings. Book of the New Sun itself has several artificial characters, and one important character is an exoskeleton used to assist human space travellers at a much earlier time than that in which the story is set. Their spaceship, having been detained near a black hole, crashed on Urth, and this character was one of the few survivors.

(Wolfe’s hero Severian treats the character like anyone else, only eventually noticing certain physical differences. Whether this is an artefact of living perhaps 100000 years from now, a dysfuction of Severian’s brain, or simply a literary trope Wolfe is utilising, is an exercise for the reader.)

@Fabio, would it be impertinent to ask you if your South American upbringing influenced your enjoyment of the book’s setting? I know I love to read stories set in the NYC metro area, works from Washington Irving to J.P. Donleavy to Caleb Carr. I also loved your story about tracking down books, recalling fondly my hunts through dusty shelves in cramped used book stores, and the exultation of finding a treasure in a 25-cent library sale. Gene knew what he was talking about when he described ‘The Book of Gold’.

@Raskos, those layers and layers of meaning are what make the book what it is. Years back, I came to the conclusion that the book is about the act and art of storytelling itself. Trying to figure out the origins of the stories told by the characters is a great part of the fun. TBotNS is like a blend of ‘The Dying Earth’ and ‘The Canterbury Tales’.

Apropos of @11, I would note that there has been considerable speculation to the effect that the Commonwealth (Severian’s country) is a future Brazil, with the river Nessus being the Amazon. The ‘men without shadows’ in the North are inhabitants of an Equatorial nation, in Central and/or South America.

@12 Gerry Quinn:

As I recall, the Gyoll (that’s the river the city Nessus is located on) flows westward rather than eastward; even if I’m wrong about this (it’s been a while), the Commonwealth is well south of the tropical forests of the equatorial regions, which apparently still exist in Severian’s time. This suggests that it’s down in Argentina or thereabouts, although to be honest I think that the geography of Severian’s time is only distantly related to that of ours. The continent that the Commonwealth is found upon probably corresponds to South America – a lot of the names for animals correspond to those of living or extinct South American species, for example, and people drink mate.

I think that the Ascians are North Americans (or from a continent corresponding to NA) – IIRC, they came from north of the equatorial regions. They’re referred to as “men without shadows” by the citizens of the Commonwealth because the two peoples first encountered one another around the Equator, in the same way as the Imperial Chinese referred to Europeans as “South Sea barbarians” because the Europeans they first encountered in numbers came to China overseas, from the south.

Along with @13, my assumption upon reading it, which I did as Timescape originally released them, was that the setting was Argentina. People drink mate, which is very common in Argentina & Uruguay, although it is also drunk in southern Brazil. And the city of Saltus is almost certainly the subtropical city of Salta in the northwest of Argentina where director Lucrecia Martel set her first 3 movies. The Gyoll could be a tributary of Rio de la Plata, or even the estuary itself, although that is huge. But as far as I know, the Plate and its tributaries flow eastward, so that’s an issue.

While set in the distant future, I don’t see Severian’s time as being far, far distant future – certainly not far enough for tectonics to have made an appreciable change in the continent. The sun is not weaker because it has aged, but because it was sabotaged. It’s being eaten from within.

The comment section is just as interesting and enlightening as the article itself. As I read the book, I couldn’t even be sure it was set on earth. I missed a lot.

For those who have read already read these books, I strongly recommend the new podcast ReReading Wolfe (home page here: https://rereadingwolfe.podbean.com/). The hosts are going through the books (as they put it) “without the literary pretense that this is the first time we’ve read them”, offering theories and interpretations, well-grounded in the chapter under discussion, but with reference to the books as a whole (and to their sequel, Urth of the New Sun, and occasional reference to other Wolfe books as well). It’s terrific. These are books that bear — indeed, demand — multiple close readings. This is one worth following.

Triskele

you do him (and Gene/Severian) a disservice by referring to him as a ‘mangy wounded dog’.

Severian’s description of Triskele makes it quite clear that he was a highly-trained and prized fighting dog. He has suffered terrible wounds apparently in a dog-fight and has been left for dead. The all-too-brief relationship between the two of them is one of the truest that Severian has with any being – as is made clear later, but let me not run ahead of these reviews! – and one of the most moving elements of the books.

I understand that GW was a great dog-lover, and that comes across every time that Triskele appears.

By the way, a ‘triskele/triskelion/triple spiral’ is a three-legged Celtic symbol, possibly with very ancient roots, and entirely appropriate as a name for a three-legged dog.

(I’m re-reading New Sun 20 years later and wondering how i missed so much the last time round!)