For millions of years, life on Earth has taken its cues from the rising and setting of the sun, and for most of human history we’ve followed the same rhythm. But if that shared connection was broken, and we each fell under the sway of our own private clock, could we still hold our lives together? One family is about to find out.

1

“Daddy?” Emma pleaded. “Why aren’t you awake?”

Sam opened his eyes and squinted toward the sound of her voice in the darkness, ready to offer whatever comfort she needed, but as he replayed the words that had penetrated his sleep she sounded not so much frightened or unwell as annoyed and censorious. “What’s wrong, sweetheart?” he asked. “Did you have a nightmare?”

“No!” Her tone was pure frustration now, as if the thing most troubling her was his obtuseness. She reached over and tugged his arm. “Why won’t you get up?”

Laura shifted beside him; Sam waited, afraid they’d woken her, but then he heard the rhythm of her breathing and he knew she was still asleep.

“Shh,” he whispered to his daughter. “Why don’t I get you a drink of water?”

He slipped out of bed and took her hand, then led her from the room and closed the door behind them before switching on the light in the passageway.

In the kitchen, he filled a cup from the sink and handed it to her. She gulped the water down eagerly, but when he took the cup back she said, “I want oats, please.”

“You can have oats for breakfast,” Sam replied. “It’s the middle of the night.”

Emma laughed. “No! It’s breakfast time.”

Sam gestured at the digital clock on the microwave. “What does that say?”

She frowned and moved her lips for a moment before announcing, correctly, “Twelve fifteen.”

“And what does that mean?”

Emma shrugged. “The power went off?”

Sam resisted the urge to congratulate her on her lateral thinking. “Sweetheart, it’s nighttime. You need to go back to bed or you’ll be too tired to get up in the morning.” He took her hand again. “Come on, I’ll tuck you in.”

“No!” She pulled free. “I want breakfast!”

Sam squatted beside her. “What’s going on? If you had a nightmare, you can tell me. You know that.”

Emma scowled impatiently, brushing off his attempt to change the subject. “Why can’t we have breakfast?”

Sam walked to the back door and opened it. “Look! It’s pitch black outside!” All he could see was the light from the kitchen spilling onto the dewy lawn; beyond that, the yard was lost in darkness. “Does it look like the sun’s coming up soon?”

Emma didn’t answer. Sam closed the door, afraid that he’d already risked giving her a cold. He reached down and scooped her up into his arms, rubbing her shoulders to warm her, and carried her to her room.

As he pulled the blankets up to her chin, she started, not so much crying, as emitting blubbery sounds of protest.

Buy the Book

Zeitgeber

“That’s enough!” Sam said. “If something’s scaring you, tell me what it is and we’ll make it go away.” He waited, but Emma didn’t take up the offer. “Okay. So close your eyes and dream about breakfast, and before you know it, it really will be morning.”

Back in his room, as he lay down beside Laura, he heard Emma leaving her bed again. He waited, hoping she was just fetching one of her stuffed animals to cuddle beside her. But after a few minutes, he still hadn’t heard a second telltale squeak from the bedsprings.

He rose and walked down the passageway to her room, then stood outside the door, listening, not wanting to disturb her if he’d simply missed the sound of her settling back in under the covers. But then he heard her harrumphing to herself.

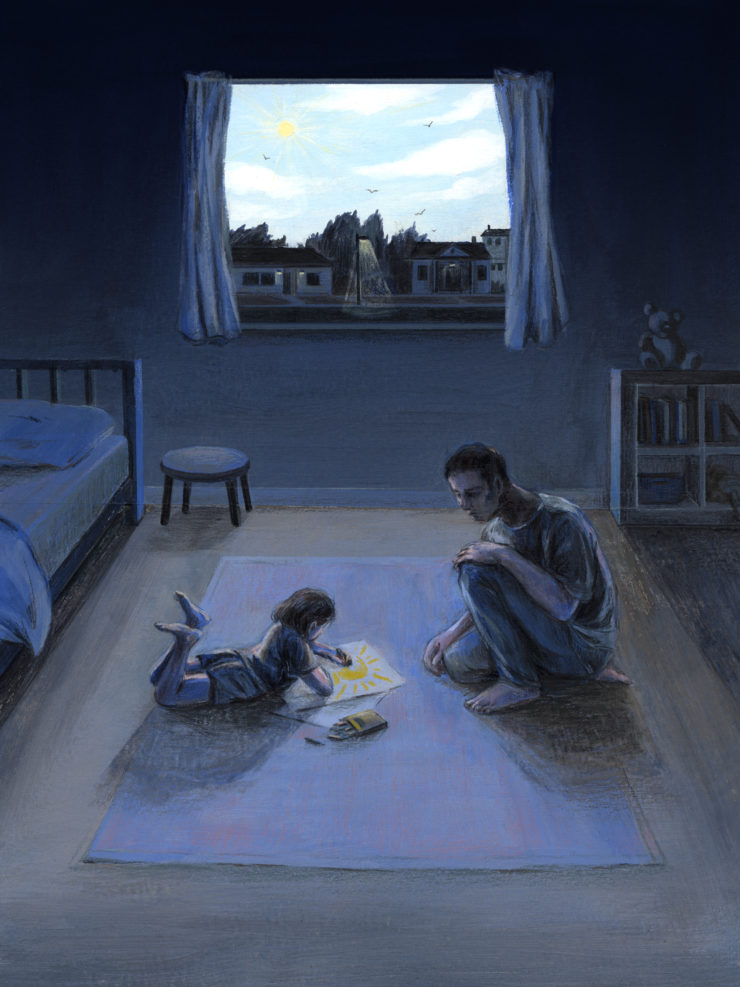

He opened the door. She was sitting on the floor in a patch of light coming through the window from a nearby streetlamp, fully dressed in her school clothes. She had a pad of paper in front of her, and she was drawing on it with her colored pencils.

“What do you think you’re doing?” Sam demanded.

She held up the paper to the light from the window. She’d drawn a yellow disk surrounded by radiating lines, with birds flying across the sky beside it.

“You didn’t believe me,” she replied accusingly. “So now I have to show you.”

2

“Are you sure you’re in control of her screen time?” Dr. Davis asked. “Sometimes parents don’t really know what’s going on.”

Laura said, “She has no devices of her own—no phone, no tablet, no TV in her room. Before this started, she’d watch TV for a couple of hours before dinner.”

“And she’d fall asleep after twenty minutes listening to one of us reading,” Sam added. “It was a pretty steady routine: in bed by seven thirty, eyes shut by eight.” He turned to glance at Emma, lying on the pediatrician’s couch, dead to the world at two p.m.—the earliest appointment they’d been able to get. But from midnight to noon, she’d had as much energy as any healthy six-year-old…just seven hours earlier than usual.

“The MRI and the blood tests rule out any kind of tumor,” Dr. Davis stressed. “And with no family history of sleep phase disorders, at this point the simplest explanation might be that she’s responding to something in her life that’s troubling her.”

Laura frowned. “Nothing’s changed for her recently. She settled into school with no problems—and she’s never been reluctant to go in the morning. Even now, the hard part’s making her wait. And when she started dozing off in the afternoons, she was mortified.”

“I’m not suggesting that she’s feigning sleepiness to get out of school,” Dr. Davis replied. “But if something’s persistently waking her at night—either some anxiety she’s feeling, or some external factor—that could be enough to disrupt her whole routine.”

Sam said, “She’s adamant she’s not having nightmares. And it’s a pretty quiet street. I’m a light sleeper myself; if the neighbors’ dog was barking, or the fridge motor was making a noise, I’d be the first to know.”

Dr. Davis scribbled something in his notes. Then he said, “I can recommend a psychologist, but the waiting list is brutal right now; you’d probably be looking at six or seven months. In the meantime, I’ll order genetic tests for all the familial sleep disorders, just in case there’s something we’re not seeing in the history, but I think that’s a long shot.”

“So what should we be doing,” Laura asked, “while we wait for all that?”

“Try to guide her back toward her old habits. Try to keep her awake a little later in the afternoons, so she’ll sleep through a little later as well. A few nudges like that, and it’s possible the whole thing will resolve itself.”

On the drive home, Laura sat in the back with an arm around Emma. Sam wasn’t sure what he’d do if he had to drive her somewhere by himself; she was far too big for her old baby seat, but the seatbelt alone couldn’t keep her from slumping.

“Do you think I should take a couple of weeks off?” he asked Laura. The substitute teacher who’d come in to cover his classes for the afternoon was always keen to do more hours.

“No, I can keep working from home,” she replied. “The firm doesn’t mind, and half our meetings are by Skype anyway.”

“What about site visits?” Sam knew she didn’t need to show up for every concrete pour, but she liked to keep a close eye on the details of every building.

“There’s nothing coming up for a while.”

As Sam carried Emma from the car, she stirred slightly, grimacing, but her eyes remained shut. “Look at that sleepy head!” Mrs. Munro called out from across the road. “Someone’s been up past their bedtime!” Laura raised a hand to her in greeting, muttering insults under her breath.

Inside, Sam got Emma into bed, then he knelt beside her and buried his face in his hands. He could feel himself trembling with relief. It wasn’t a brain tumor or a neurological disease. Most likely, it wasn’t anything dangerous at all.

Her sleep was out of phase, but it was a phase she could grow out of. All they had to do was gently pull her back into synch with the rest of the world.

3

“Big night on the town, sir?” someone called out.

Sam’s eyes snapped open, and half the class burst into laughter. “Very funny,” he said. “But you’ve only got ten minutes left, so you should probably save the jokes until then.”

He punched the side of his leg under the desk and stared at the clock at the back of the room, wondering if the collective will of the students, desperate for more time to finish the test, could actually freeze the minute hand in place. He and Laura had got through months of broken sleep when Emma was teething—but back then, after their interventions, she’d usually drifted off for a while. Now, once she was up, she stayed up, and even if she did her best to be helpful and pass the time quietly on her own, Sam felt too guilty to let her sit alone in her room, drawing, for hours on end. He wasn’t sure anymore where the line lay between unforgivable neglect and prolonging her wakefulness by making it more tolerable, but he couldn’t sleep through the night as if nothing was wrong while his daughter was going stir-crazy.

After the siren rang and he’d gathered up the tests, he detoured to the staff room. He’d graduated to four spoonfuls of instant coffee and three of sugar; he usually drank it black, but now he added just enough milk so he could gulp it down quickly without burning his mouth. The brown sludge made his teeth ache and his stomach clench, but it cranked up the volume on the white noise buzzing behind his eyes, summoning fragmentary thoughts from the static to ricochet around his skull. However remote this state was from normal consciousness, the sheer rate of random mental activity ought to be enough to keep him from dozing off.

As he walked across the carpark, acid rose into his throat. He could feel his blood pumping, but it was not so much a rush of vigor as a sensation akin to the aftermath of hitting himself with a hammer. This wasn’t going to work; even if he’d managed to immunize himself against micro-sleeps for the next twenty minutes, he had no more faith in his judgment and reflexes than if he’d just drained a bottle of whiskey.

He looked around. “Sadiq?”

Sadiq paused, stooped at his open car door with an armful of paperwork.

“Any chance I could get a lift with you?”

“Sure.”

Sam approached, hoping his gait didn’t appear quite as unsteady as it felt. “Thank you.”

“Car trouble?”

“No. I was up half the night with Emma, and if I drive…”

Sadiq nodded. “No problem.”

As Sam buckled in beside him, Sadiq asked, “So Emma’s been sick?”

“Yeah.” Sam hesitated; Sadiq’s son had muscular dystrophy, which seemed to demand a recalibration of his own difficulties. “Something’s messing with her body clock. She wakes up in the middle of the night, and then she’s completely alert for the next twelve hours.”

Sadiq was silent as he drove through the carpark; Sam assumed he was trying to frame a polite response to such a trivial complaint. But as they turned onto the road he said, “I know how annoying it can be when people tell you they know someone with the same medical problems. Ninety percent of the time they have no idea what they’re talking about.”

“Okay.”

Sadiq grinned. “So take that as given, and feel free to ignore this. But my brother-in-law has the same symptoms.”

“Yeah? What did they diagnose?”

“Oh, he won’t see a doctor. He insists it’s not just insomnia, but he’s too much of a tough guy to admit that he might not be able to get back to normal by sheer force of willpower. It’s driving my sister crazy.”

“Hmm.” Sam’s eyelids fluttered closed and he pictured a scowling pugilist, tormented in the small hours by thwarted ambition and a history of concussions. What could a man like that possibly have in common with a six-year-old girl?

Sadiq said, “The thing is—and I know, Dr. Google is not our friend—but Noor did some rummaging around on the web, and there seem to be an awful lot of similar cases.”

Sam forced his eyes open. “The last time I looked, all I found were people burbling about their digital detoxes and their valerian enemas.”

“Yeah, and maybe this is nonsense too. But I’ll get her to send you a link, and you can make up your own mind what it’s worth.”

When Sadiq dropped him off, Sam opened the front door as quietly as he could, and made his way to the spare room where Laura had set up their shared home office.

“How was she?” he asked.

“When I picked her up at lunchtime,” Laura replied, “she said she wasn’t tired and she begged me to let her stay. And then she didn’t fall asleep until almost two o’clock.”

“That’s progress, isn’t it?” Sam hadn’t been keeping records of the time she woke; he’d been trying to leave her on her own until two a.m. or so, when she’d already been up for a while. But it did look as if the whole cycle was moving forward by about five minutes a day.

Laura seemed unwilling to raise her hopes too high. “What happened to the car?” she asked.

“I didn’t want to drive. I’m kind of wasted.”

“Okay. Why don’t you grab some sleep right now?”

“It’s my turn to cook dinner.”

“Forget it. I’ll order takeaway.”

Sam managed to stay awake just long enough to get undressed and crawl beneath the sheets. Three hours later, he was roused by the scent of fried rice. His caffeine binge hadn’t kept him from sleeping, but it had thrown enough grit into the clockwork that he emerged from the process out of synch with himself: ravenous as if it were morning, chilled to the bone as if it were three a.m., and afflicted with the kind of headache and parched mouth that brought back distant memories of nights spent clubbing, when he’d staggered home at dawn and woken at noon.

When he walked into the kitchen, Laura was taking the lids off the food containers, sending aromatic vapors wafting up from the table. Sam listened for any sound from Emma’s room, but there was nothing. “She loves Chinese food,” he said. “I don’t know how she can sleep through this.”

As he ate, he began to feel better. It was seven o’clock now; if Emma hadn’t slept until two, she might not wake until one, so maybe he could sleep again from ten until…three? Leaving her on her own for a couple of hours wasn’t torture, and if he didn’t start setting limits he’d end up either dead in a ditch or sacked for incompetence.

“How was work today?” he asked Laura.

“All right.”

“It’s not getting you down? Being stuck here?”

She frowned, thinking it over. “I probably get more work done in a day, even spending a couple of hours with Emma. It’s a bit numbing when I’m alone, though. Some of my colleagues are pretty annoying, but sitting at a desk in a silent house…when you’re focused, it’s fine, but when you stop and look around, it feels like you’re the last person on Earth.”

When Sam had cleared the table, he glanced at his phone. Sadiq’s sister, Noor, had emailed him a link.

Laura was in the living room, browsing the menus of the streaming services in search of something that would help her unwind. Sam walked down to the office and opened the link on the desktop.

Noor had found a long thread on a medical support group forum. Sam was generally skeptical of such venues, but at least this one was well-organized. The thread in question was dedicated to sleep-phase disorders where the sufferer had no family history or genetic markers, no psychiatric illness, no shift work or frequent long-distance travel, and no apparent brain injuries, tumors or lesions.

Despite this niche-like specificity, there were tens of thousands of individual posts. A moderator had helpfully pinned one entry to the top of the list, giving an overview of the results from a survey of the thread’s participants, to which more than three thousand people had responded. The sufferers seemed to lack any particular concentration by age, sex, occupation, ethnicity, or geography, compared to the demographics of the forum as a whole. People’s “phase at onset” spanned the full gamut, from twelve hours’ advanced to twelve hours’ delayed—but however things had started, nobody’s phase remained unchanged relative to clock time. It usually slipped forward by a few minutes a day, but for a fraction of the group it went in the other direction. And as the moderator noted, this scatter was more or less in line with the range of endogenous circadian rhythms reported by sleep researchers for healthy volunteers who’d been deprived of sunlight and social cues, leaving their body as the only time-keeper.

Sam scrolled down a little further and skimmed the highest-rated posts, expecting to find testimonials to some suitably fashionable cure. But if there was snake oil on offer here, it had been down-voted out of sight; the majority opinion was that nothing worked. People had tried everything from phototherapy and warm baths to melatonin and modafinil, but their body clocks just kept stubbornly cycling at their natural rhythm, close to but not exactly twenty-four hours, oblivious to every natural or pharmacological “zeitgeber” that might have been expected to jolt them back into synch.

A sidebar offered links to academic sources on sleep disorders. Sam followed the one on “free-running sleep” to a review article in a medical journal. The vast majority of cases where people’s body clocks ceased to be entrained by the outside world involved total blindness, where the patient had lost, not just vision itself, but the retinal ganglion cells that were sensitive to ambient brightness. Sighted people with the disorder were supposedly rare, and often had tumors, head injuries, or other detectable causes of damage to the suprachiasmatic nucleus that orchestrated the circadian rhythm. In one study, they’d also been found to have significantly longer cycles than normal—unlike the people on the forum.

He heard Laura approaching. “What are you looking at?” she asked.

Sam described what he’d read so far, trying to downplay the pessimistic conclusion. “I’m sure there’s a selection effect here,” he said. “Anyone with a problem that went away quickly probably wouldn’t post on a site like this.”

But Laura seemed intent on preparing for the worst. “If Emma’s a free-running sleeper now, how often will she fit in with a normal school day? To really be able to concentrate, she’d have to be awake by seven, but not up so early that she’s falling asleep before five. That’s a three-hour window to wake in, between four a.m. and seven a.m.—one-eighth of the clock. So for a five-week block in every forty she’ll be fine, but for the rest…”

Sam said, “If it really does come to that, I could always home-school her. But it’s only been a fortnight! Maybe she’ll just keep waking later and later until she gets back to normal—and then she’ll be so happy that she’ll slam on the brakes, and that will be the end of it.”

4

Sam arrived for the first class of the new term feeling sharp-witted and thoroughly prepared. The day had started as well as he could have hoped: he’d woken at five, found Emma still asleep, then spent the hour until she rose reviewing his lesson plans. But each time he turned away from the blackboard to gauge how well his line of exposition was getting through, his gaze was drawn to the empty chairs in front of him, and he lost his thread completely.

A third of the class was missing. A cynical part of him was tempted to attribute this to copycat malingerers, but that couldn’t be the whole story: two of his most enthusiastic students had failed to show up. When he asked a question, he still found himself reflexively preparing to deflect their responses to give someone else a chance to answer, and the silence that greeted him instead was unsettling. No one had died, or was even ill in any normal sense, but the thinning numbers still felt like the sign of some terrible loss.

At lunchtime, the staffroom was less starkly depleted, but everyone in sight looked anxious. Sam joined one dispirited group.

“We need to start doing something more,” he said. “Sending students worksheets and hoping they’ll pick up what they miss from YouTube lectures at three in the morning isn’t going to cut it.”

“So are you volunteering to come in at three a.m.?” Gloria asked. “And if you are, who’s going to teach your regular classes?”

Sam said, “The overall numbers aren’t changing; there are exactly as many teachers per student across the district as before. We just need to reorganize things, matching up students and teachers by phase. I’m not free-running myself, but I’d be happiest following my daughter’s phase. If she could go to school when it suited her, I could work those hours, teaching any students in the area who were on the same schedule. My old classes would have to be merged with those from the closest two or three other schools—”

Sadiq cut him off. “That’s not going to work. The logistics for keeping the buildings open twenty-four hours a day would be unmanageable, let alone shuttling kids across three suburbs in the middle of the night. If students can’t make it in normal hours, we need to be flexible, but not like that. We need to use software, video lectures, whatever it takes to keep them up to speed. But they’ll have to do it from home.”

Tom regarded them both as if they’d lost their minds. “Whatever’s causing this,” he said, “it’s not going to last forever. In a couple of months, we’ll be back to normal.”

“You think it’s going to burn itself out, like a bad flu season?” Sam replied. “The way it’s spreading doesn’t look like an infection. Nor does the biology: there’s no inflammation, no antibodies.”

Tom snickered. “Yeah, well, if ninety percent of it’s ‘viral’ in a different sense, what would you expect?”

“Hardly ninety percent,” Sam retorted. “And even if you think that many kids don’t want to be here, most adults have nothing to gain by faking it; they don’t have enough paid sick leave or income protection insurance that they can lie in bed all day—and all it would take to prove that they’re frauds is one polysomnogram.”

Tom was unrepentant. “People manage to do shift work all the time. If a nurse can turn up for a graveyard shift, no one has any excuse not to show up when they’re needed.”

Sam was growing angry now. “Some people adapt better to shift work than others—but if they do, it’s because their circadian clock is responding to all the timing cues: they’re out of bed, moving around, eating, exposed to bright light. The whole problem for free-runners is that none of those cues affect them! It’s no different from being blind to sunlight—except you’re also blind to temperature, food, exercise, social interaction, and every jet lag pill ever invented.”

Tom didn’t reply, but he adopted the pained expression of a martyr badgered into silence. He knew the truth: anyone with a spine would grit their teeth and rise from their bed to meet their obligations.

When Sam picked up Emma, he watched the elaborate ritual of her parting from her best friend, Natalie. After the hug that was meant to finalize things and let them go their separate ways, they turned back to each other no less than five times, with afterthoughts and reminders.

“How was school?” he asked, as she approached.

She shrugged. Sam didn’t press her; he had no need to quiz her to see that she was perfectly alert. When she’d first resumed normal attendance, she’d spent half an hour telling him how happy it made her, but by now she was probably just taking it for granted. He hadn’t had the heart to warn her that the situation might not last.

“Olivia fell asleep before lunch,” Emma said, as Sam unlocked the car. “And Mitchell fell asleep after lunch. And Karen didn’t come until after recess because she didn’t wake up until then.”

Sam said, “Yeah, a lot of people are having the same problem as…” He cut himself off, unwilling to commit to any particular tense. As you had? As you have?

“But how will everyone stay friends if they can’t see each other?” Emma demanded indignantly, as if this whole state of affairs had been decreed by someone who just needed to be told what a terrible idea it was.

“People stay friends when their friends get sick,” Sam replied. “Or when they go and live somewhere else. You don’t have to see someone every day to be their friend.”

“No,” Emma agreed reluctantly. She adjusted her seatbelt. “But I want to.”

Sam pulled the door shut beside him. He said, “Do you want to stay friends with Natalie?”

“Yes.”

“Then you’ll stay friends with Natalie. Even if it’s hard, even if it’s complicated, you’ll find a way to do it.”

When they arrived home, Laura’s car was in the driveway. Emma ran inside, calling out to her mother; Sam had thought she was going to be on site all day, but maybe there’d been a change in the schedule.

He found her in the bedroom, sitting on the edge of the bed, staring at the wall. Emma had stopped in the doorway, confused.

“What’s wrong?” Sam asked.

“There was an accident,” Laura said.

He turned to Emma. “Can you go and put your books away?”

Emma nodded uneasily and retreated.

Laura said, “One of the operators swung a crane into the scaffolding. Three people are dead, and five are in hospital.”

Sam bowed his head. It sounded like something that should have been impossible. “So was it equipment failure?”

“No,” she replied. “We’ve got video from inside the cab. The operator just kept his hand on the lever.”

“Why? Was he having a heart attack?”

“No. He closed his eyes and fell asleep.”

5

Halfway through the lesson on Al-Karaji’s triangle, two new students entered the room quietly, hung their dripping umbrellas over the bucket, and took seats at the back. Sam paused to greet them, then resumed, glad he’d managed to iron out the sound problems that had plagued his last few recordings, so they’d be able to play everything back from the start if they needed to.

The rain came down more heavily, slanted now, striking the window panes on the southern wall with tympanic effect, but he raised his voice and pressed on. “The number of ways you can get x cubed y squared in this row is the number of ways we got x squared y squared in the row above, six, plus the number of ways we got x cubed y, four, for a total of ten. Every time, we’re just adding two numbers from above to get the ones below and in between them. So we ought to be able to guess a formula for the numbers in any given row, and then prove it by induction.”

Hands shot up, gratifyingly, and Sam wrote each proposal on the blackboard. He glanced at the storm outside, and dared to marvel at the one small upside of the syndrome: not long ago, on a winter’s afternoon in a cozy room like this, half the class would have been dozing off, but even at two in the morning these runners seemed impervious to everything that might once have been conducive to a surreptitious nap.

At the end of the lesson, a group of students hung around, hunting for fresh identities between the binomial coefficients while they waited to spend a few minutes with their other-phase friends who were only now arriving. Sam walked down the corridor to the grade three classroom, where Emma was in the middle of a cross-temporal exchange of her own. She stood in a group of a dozen other girls, but it was easy to tell from their states of dampness that about half had just come in from the rain.

He kept his distance, reluctant to do anything to curtail the meeting, but after a couple of minutes the new teacher arrived and ejected everyone whose school day was officially over. Sam fished his phone from his pocket and checked the carpool app; he was scheduled to give three of Emma’s friends a ride home. “Sandra? Martin? Chloe?” he called out hopefully. No one responded, but the app showed him mug shots; he spotted the kids and corralled them toward the car.

As he drove through the rain, Sam concentrated on the road, but it was impossible to ignore his passengers’ conversation. “We’ll visit you in the hospital,” Martin promised Chloe.

“You won’t be awake for visiting hours,” Chloe replied.

“They should let us come any time!” Sandra protested.

But Chloe was resigned to the impending separation. “I won’t be awake when you want to come.”

When Sam had dropped off all three, he asked Emma, “What’s the time in your head?”

“Ten past three.”

He checked his watch. The second row of digits, which he’d programmed to follow her phase, was only two minutes out—and Emma never claimed greater precision than five minutes herself.

“So Chloe’s getting the implant?”

“Yes,” Emma confirmed. “Her parents aren’t rich, but her grandmother’s paying.”

Sam hesitated. “You know it’s not the cost that’s stopping us? We could probably get a loan to cover it. I just don’t think the safety record’s good enough yet.”

Emma said, “I don’t want it anyway.”

“I know. But in a couple of years, when the surgeons have had more practice and the technology’s improved…”

Emma sighed, irritated. “I told you, I don’t want it. Ever!”

As soon as they pulled into the driveway, Emma flung the door open. Sam watched as she ran to the porch; he could see her umbrella cinched in place in one of the net pockets at the side of her backpack.

He followed her, taking more care to stay dry, and by the time he was inside she’d disappeared into her room. He took his shoes off and trod lightly down the hall to the office. It was just after four, and Laura would be up at six; he could probably get most of his marking done before the three of them were due to have breakfast together.

He switched on the computer and checked his news feed. A story that had broken fifteen minutes ago had rocketed to the top: “Gang ‘hacked your sleep,’ wants cash for cure.” Sam assumed it was a beat-up, but he followed the link anyway. Nothing was going to rival the Onion’s “Uber Sleep rolls out replacement for Sandman; CEO plays down ‘teething problems,’” but intent had long ago ceased to be a prerequisite for satire.

According to the story, a group calling themselves the Time Thieves had claimed responsibility for the free-running syndrome, and were soliciting offers from governments for exclusive access to the cure. The starting price in this auction was a trillion US dollars.

“This is less than one percent of the estimated loss to global GDP to date,” the self-proclaimed biohackers had noted, citing a study by a team of World Bank economists to back up the figure. Fair enough, then, Sam thought. The email scammers offering him ancient Chinese herbs to realign his family’s circadian rhythms for sixty dollars a bottle were clearly undercharging.

He was about to close the browser and get to work when he realized he’d skipped a paragraph near the top of the story, distracted by the astronomical sum below. “As evidence for their claims, the Time Thieves have published a digital key that decrypts a coded message describing the condition’s symptoms, which was posted on social media accounts six months before the first cases were reported.” Sam was skeptical; would it be that hard to hack a Twitter or Facebook post so it seemed to predate the outbreak? But then he searched for other coverage of the story that went into more technical details.

The times in question were not just social media metadata. Digital hashes of the message had been sent to half a dozen reputable time-stamping authorities, who’d used their private encryption keys to sign and date what they’d received, allowing anyone to verify that the message really had been signed at the times being claimed. But to counter any suggestion that the top six cybersecurity organizations in the world might have all been hacked—or been willing accomplices to fraud—the Time Thieves had also embedded the same hashes into several globally distributed block chains that offered their own kinds of certification.

Sam read through the full text of the decrypted post. Though its authors spelled out the symptoms of the coming plague clearly enough, they were coy when it came to the biochemistry, sprinkling in just enough jargon to suggest that they knew their target intimately, without revealing anything about the particular spanner they’d thrown into the works. A virus? A toxin? These and other details remained behind a very high paywall.

The current ransom demands had been written in a tone befitting a Sotheby’s catalog, but this screed from (supposedly) two years ago was a boastful, pretentious rant, full of the kind of raw self-aggrandizement only to be expected from someone who believed they’d devised a foolproof means to take the whole world hostage and come out the other end wealthier than a middle-sized nation. There were even some bad puns about the WannaCry computer virus—two of the key proteins in the circadian clock being the cryptochromes, CRY1 and CRY2—as the Time Thieves gloated about their own, stupendously greater feat. Sam couldn’t help being goaded into anger, which in turn swayed him toward belief, though the fact that the document rang true as the heady manifesto of a gang of sociopaths would be by far the least challenging of all the forgeries required if the whole thing was actually a hoax.

The response from political leaders so far had been cautious; everyone who’d spoken had condemned the extortion attempt, but they’d described any link to the syndrome itself in hypothetical terms, and stressed that law enforcement agencies were still investigating the claims.

Sam rather hoped that behind this bland facade, someone had already located the perpetrators and dispatched a team of commandoes to liberate the cure with extreme prejudice. Along with the economic damage, there had been at least half a million deaths. His own family had been lucky; as the gears that had linked them to the world had stopped meshing, they’d managed to adapt to the changes without descending into poverty. But all the accidents on the roads, in the air, and at sea, all the fatalities at building sites and factories were no different from the acts of a sniper, and the slow torture as loved ones had been dragged into different phases was as cruel as any forced exile. He’d gladly see the fuckers who’d done this reduced to bloody smears on the walls of their basement lab.

He closed the browser and tried to calm himself. He had work to do, and neither his Zero Dark Thirty fantasies nor any other follow-up was likely to be imminent. He believed that these criminals had done what they claimed, but that didn’t guarantee that they were in possession of a cure, let alone that anyone on the planet would be willing to pay what they were asking.

6

None of Sam’s students could focus on the lesson he’d prepared, so he made the best of the situation.

“A hash function takes some data, like a string of text, and gives you a single number that’s a whole lot shorter than the original message.” He drew a big box full of squiggles, joined by an arrow to a small box full of digits. “The correspondence can’t be unique, though; there are billions of messages that have the same hash code. So why doesn’t that matter? If someone shows you a message today that gives the hash X, along with proof that someone you trust saw that same number, X, two years ago…why should that be enough to persuade you that they actually wrote the whole message back then?”

The tactic seemed to work, so he stuck to the same theme for the next few days, but there was only so much cryptography he could teach before it started squeezing out everything else. And then just when he thought he’d exhausted the subject, the Time Thieves dumped a truckload of new material into his lap.

Sam gave in and showed excerpts from the videos. The biohackers had apparently spent months testing their products on macaques, and they were offering up thousands of hours of recordings as evidence that they possessed both the agent behind the syndrome and an effective cure. Every shot contained a bank of screens behind the cages, showing international news channels playing live, along with a certified time-stamped hash of a previous, rolling segment of the video, to prove that the backdrop was not just a recording. But that left only the narrowest of windows between the original broadcast and the time stamps, so if everything involving the animals had been added with CGI, it must have been generated in something close to real time—a feat most experts judged unlikely. If the images were genuine, then according to a team of biologists with the patience to watch much more of the footage than Sam had, they showed that the macaques had entered a free-running state at the start of the experiment, and then abruptly returned to a normal circadian rhythm three months later.

“Maybe they put in brain implants before the experiment started—before the cameras started rolling,” Angela suggested.

“Good point,” Sam conceded. There was always going to be some potential loophole; macaques were too long-lived for the experiment to stretch back to their birth, and shorter-lived species like mice were too different in their circadian biology.

Ehsan said, “The technology didn’t exist two years ago, did it?”

“Not that we know of,” Angela replied.

“Yeah, but how many different things are these geniuses meant to have invented?” Ehsan retorted. “We’re talking about implants, now, because all the millionaires are getting them…but I bet it never even crossed these people’s minds.”

“Forget implants,” Nora interjected. “They could have trained these monkeys to wake and sleep for any reason: some sound we can’t hear, some smell. They could be pulling all kinds of invisible strings.”

Sam let the debate run on, only intervening when necessary to keep it civil. These kids’ lives were in the balance; he couldn’t tell them to drop the subject and get back to the things they’d be tested on.

On the way home, after he’d dropped off Emma’s friends, he asked her if she had any questions about the Time Thieves. He’d done his best to give her a sense of why most people believed their claims, but he wasn’t sure if she’d really taken it in. “If there’s anything you don’t understand, I can try to explain it more clearly.”

“I don’t care about of any of that,” she replied. “I just hope no one pays them, because it would be a big waste of money.”

Sam kept his eyes on the road. “Why would it be a waste, to get back to normal? Don’t you miss seeing more of your mother?”

“She’s still around. I still see her. She doesn’t have to hold my hand every day.”

Sam fought to conceal his dismay. He’d wanted his daughter to adapt, to be resilient. And she wasn’t being cold toward Laura; this was just the reality she’d grown to accept, as surely as if the two of them lived on different planets that only came into proximity for brief stretches at a time.

In the street ahead, there were lights showing through the windows of most of the houses. The traffic around them was barely less, at four a.m., than when they’d set out the evening before. And if none of that felt strange to him anymore, how could it feel anything but normal to someone who’d lived the last quarter of their life this way?

“I don’t know what will happen with the money,” he said. The extortionists had made a trillion dollars sound like a bargain, which had to irk all the biochemists who’d been slaving away trying to understand the syndrome with a fraction of that as their budget. “But my hunch is it won’t be long before we can all have the sun on our faces again.”

Emma was quiet for a while, and Sam thought she’d let the matter drop. But as they approached the house, she replied, “I already have the sun inside me. The one you see up in the sky doesn’t count.”

7

Three weeks after the ransom demands appeared, a group of neurologists, biochemists, and cell biologists from seventeen nations announced a cure of their own. Sam really didn’t care if this was just a cover for paying off the hackers; whether the Nobel committee handed out medals to the researchers and pronounced them the saviors of the world, or some investigative journalist unmasked their work as a recipe their governments had bought on the sly, it would make no difference to whether the antidote worked or not.

But the timetable for the new, synthetic zeitgeber to hit the shelves kept changing. There had to be safety trials, starting on animals; no one could acknowledge prior experiments on monkeys, and in any case Sam wouldn’t have wanted the Time Thieves’ offering blindly accepted as benign. Then there was the question of manufacturing the substance in sufficient quantities for a fifth of the world’s population to take a few milligrams every day.

With each delay, the old scammers bombarded his inbox with new fervor, now offering bootleg versions of the untested cure. Sam remained patient; so long as the end was in sight, he could get through another year the way he had the last two. He’d learned to cherish the brief, glorious “spring,” when he woke with the sun and Laura emerged from what seemed like hibernation, to share his bed, and two or three meals a day. And when it slipped away, and he was dragged into the season of broken sleep through the heat of the morning, he told himself: This is the last time. I can live with anything, one last time.

8

“I don’t want it!” Emma declared vehemently.

“I know,” Sam replied. “But what if you try it for a week, to start with? Just to see what it’s like?”

“No!” Emma was close to tears.

Sam spun the bottle of pills on the table, seeing if he could get it to rotate like a top, but the rattling contents destabilized it. “Then talk to me,” he said. “What is it that you think will be so bad?”

“Everything’s better the way it is,” she insisted. “Why do you want to force me to stop being a runner?”

“Because all the other runners are going to stop. If you try to keep going, you’ll be all alone.”

“Only because they’re being forced as well!”

“Maybe some of them,” Sam conceded. “But we can’t keep the schools open all night for a couple of people. And if it’s been hard to keep up with your friends already, if you don’t switch back with them it will be even harder.”

Emma stared sullenly into her cereal bowl. Sam felt a brief flicker of regret for declining the suggestion from well-meaning colleagues to grind the pills up and slip them into her food.

She’d been awake since three a.m., but Sam had hardened his heart and insisted she not eat until six. This was Realignment Day, and all the zeitgebers had to be lined up in a row. In the end, he’d compromised; it was half past five, and the sky wasn’t dark anymore. Even on Sunday mornings, Laura usually woke at six, and Sam was hoping he could get all the drama over before she joined them.

He rose from the table and switched off the light, then opened the kitchen blinds fully to let the dawn fill the room.

He said, “Remember the time before this happened? You’d always wake up with the birds.” He paused to let her hear the singing from the trees. “And you’d be smiling, full of energy, brighter than anyone else at that hour. Would it be so terrible, going back to that? Were you unhappy then? Honestly?”

Emma said nothing, but after a moment she picked up the pill from the table and swallowed it, then washed it down with orange juice.

He heard the bedroom door open; Laura padded down the hall. “Don’t eat yet!” she implored them. “I want to make pancakes!”

Emma glanced at her cereal, already wet with milk. Sam leaned down and whispered to her, “It’s all right, you can have both. Just finish it while she’s in the shower.”

9

“So we factor this term in the denominator…into what?” Sam turned from the blackboard and looked around the room. “Come on, it’s easy! Anyone?”

Half the class offered no acknowledgment that he’d spoken, while the rest stared back at him uncomprehendingly, as if he’d asked them to compute the square root of a fish. He was facing a new mix of students, but he knew quite a few of them from the runners’ classes, and he knew what they were capable of. “Elena?” he prompted. If she couldn’t answer him, who would?

“You want to cancel one of the terms above?” she struggled.

“Right,” he replied encouragingly. “And that would mean…?”

She frowned and shook her head. “I’m sorry. It’s too hard.”

Sam surveyed the room. No one looked sleepy; if anything, they seemed wired, jittery with nervous energy. The holdouts wouldn’t have shown up at all; any ex-runners here must have dutifully taken their pills.

He glanced out the window. Walking to class beneath the blue sky, picturing the same scene repeating for a thousand days to come, he’d been as elated as if he’d returned from the dead. Surely he wasn’t the only one who felt that way?

“How’s it going for you?” he asked Elena.

“What?” She blinked, confused.

“Are you getting used to the new routine?”

Elena seemed lost for words. “Sure,” she managed eventually. “I’m sticking to the schedule.”

In the staffroom at lunchtime, Dan compared notes with his colleagues. “Oh, the runners are hopeless!” Tom declared bluntly. “I don’t know what your special schools were teaching them, but it’s going to take them months to catch up.”

Gloria said, “They do seem to be struggling. Maybe they’re still a bit jet-lagged from the shift.”

Tom rolled his eyes. “Wasn’t the whole point of the magic potion we shelled out for that it was going to bring them absolutely back into synch?”

Sam could only half follow the accounts of the cure; all he knew was that it helped phosphorylate some crucial proteins in the cells of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, a process that the syndrome’s sufferers had lost the ability to perform in response to the normal cues. Sunlight itself still couldn’t imbue them with wakefulness, but if they took the pill in the morning, the biochemical upshot was meant to be the same.

“Everything takes time,” he decided. “Even if it’s only old habits that they’re fighting. A few more weeks, and they should be back to normal.”

That night, the news showed thirty-eight people in handcuffs and orange jumpsuits paraded before the cameras in Shanghai. Prosecutors were claiming that they’d conspired to adulterate a fire-retardant chemical that had been applied to tens of thousands of different products: clothes, toys, furniture. If that was true, the cause of the syndrome might eventually be eliminated worldwide, as all the polluted items were identified and destroyed.

Or just preemptively destroyed. Sam kept Emma distracted while Laura went through her room with a garbage bag.

“What’s it like, seeing all your friends at the same time?” he asked. She’d hardly talked to him for the last few days, but however resentful she was at being pressured into taking the zeitgeber, the silent treatment couldn’t last forever.

“They’re not my friends anymore,” Emma replied.

Sam smiled at this hyperbolic declaration; playground politics could be tough for nine-year-olds, but the grudges rarely lasted long.

“Why not?” he asked.

She turned to Sam with a listless expression. “No one’s the same as before.” Her voice was flat; the last thing she was being was dramatic.

“I think the ex-runners are all a bit…” He didn’t know quite how to finish that. No one was dozing off, or zoning out. But everything seemed to be harder for them.

Emma said, “Before, it didn’t matter if it was day or night; we had our own sun inside us, and when it was up, it was brighter than the old one. Now you want us to pretend we don’t see it anymore.”

“It’s a big change,” Sam conceded. “It will take time to adjust.”

Emma smiled thinly. “The pills say wake up, and we wake up. We won’t ever fall asleep at the wrong time again. But it’s like being an animal in a factory farm, pushed along between the rails, going wherever you want us to go.”

Sam’s gut tightened. “You don’t mean that. Everyone has to follow some kind of routine; that’s hardly the same as being in prison. You’ll get used to it again. You just need to give it time.”

Emma gazed at him defiantly for a second or two, but then the energy she’d summoned ebbed away, and she turned back to the TV.

10

Laura shuddered fitfully, a sign that she was dreaming, but then she became ominously still. “Aren’t you ever going to sleep?” she asked Sam, exasperated. She turned to the clock beside her. “It’s a quarter past two!”

“I’m sorry.” He didn’t quite know how he managed to disturb her just by lying motionless beside her, but her ability to sense his wakefulness even as she slept only made the prospect of him joining her even more elusive. “Do you want me to move into the office?”

“Don’t be stupid. Those days are over.”

“Maybe they shouldn’t be.”

Laura raised herself up on the pillows and stared at him. The room was almost in darkness, but Sam’s eyes had adapted and he could see her face well enough.

“We can’t just give in to her,” she said. “It was one thing when she had no choice—and when the whole world was willing to accommodate the runners. But if she goes back to it now, it’ll ruin her life. What kind of job could she have? What kind of family?”

“And if we’re crushing all the joy out of her, what will that do?” Sam didn’t want to believe it himself, but he saw it on the faces of the other ex-runners every day.

“This was her thing,” Laura replied. “It made her feel special, and now she’s missing it. It’s like when they moved the children out of London into the countryside during World War Two, to escape the blitz. It was an adventure while it lasted, but now it’s just…rationing and austerity and having to be normal again.”

Sam couldn’t deny that there might be some truth to that. Even in his early twenties, the freedom to stay up all night had seemed sweeter than any other perk of adulthood. If he’d been granted the same ability at Emma’s age, it would have felt like he’d conquered the world, and he would never have given up the power willingly.

“I’m not saying she’s dishonest, at heart,” Laura added. “But she’s nine years old, and she wants what she wants. When I was ten, I faked an illness for three months, without a moment’s compunction. Everyone thought I was an angel back then, but I would have said anything to get my own way.”

At breakfast, as Sam poured himself a third cup of coffee, Emma glanced at him knowingly: The pills say wake up, and we wake up. But unlike him, she’d slept through the night; he’d tiptoed into her room to check, afraid he might find her on the floor making sketches in the dark.

At school, his lessons went like clockwork, and not in a good way: he read from his notes, and transcribed them to the blackboard, barely thinking about what he was saying. His students dutifully wrote it all down. He didn’t pause to ask any questions, as much afraid that he’d lack the concentration to frame them properly as he was that nobody would offer an answer.

In the staffroom, he sat at a table by himself, staring at the noticeboard on the opposite wall, not so much drifting toward sleep as hovering on the verge of a waking hallucination.

Someone clapped him on the shoulders. “You look like shit,” Sadiq announced cheerfully, pulling up a chair.

“But I showed up,” Sam replied. “That’s what we do, isn’t it? Because everything would fall apart if we all just followed our own rhythms.”

“Yeah, very funny. I’ve got to admit it, you proved me wrong: you and your friends made the whole thing work.”

“We did, didn’t we?” Sam managed a bemused smile. “The Apollo missions, the Manhattan Project, Bletchley Park…and the runners’ schools.”

But the government was never going to let them start up again. It was an open secret that they’d paid their share of the ransom, and whether or not they ever managed to claw the money back from the prisoners’ scattered cyptocurrency accounts, they expected that to be the end of it. No one wanted to hear that the cure that cost so much was worse than the disease. Sam didn’t want to hear it himself.

That night, exhaustion broke the spell: he fell into bed at nine and slept soundly, until Laura shook him awake at half past six. He hadn’t even heard the alarm.

His newfound clarity only made his classes more disturbing. He obtained an official list of ex-runners from the office, so he wouldn’t be relying on his own experience of who he had and hadn’t taught before—and the deficits they were suffering as a group went from anecdotal to indisputable. These kids showed up, more convincingly on some levels than any sleep-deprived caffeine zombie, but…screw the somnograms and the body temperature charts from the clinical tests that had given the green light to the zeitgeber, because his students were not okay, however wide-eyed and ambulatory the pills rendered them.

When he raised his observations with Laura, she was skeptical. “Just because Emma’s not the only one dragging her feet doesn’t mean there’s anything more going on here than a collective sulk.”

“Really? You think my seventeen-year-olds—with university admission and job prospects at stake—are willing to shoot themselves in the foot…because they want to spend their nights, not at wild parties, but with me or some other teacher, talking about exactly the same things as we talk about by day?”

Laura was unmoved. “Some might be sulking, some might just be suffering from the disruption in their routine: a change of school, a change of teacher. You don’t have any evidence that it’s anything more.”

And Sam still wanted to believe that she was right: that the world would be restored to order, soon enough, just so long as everyone kept their resolve and didn’t pander to a few ungrateful runners.

“Are you feeling any better?” he asked Emma, on the drive home.

She didn’t answer. He glanced at her; she was gazing out the passenger window. “Did you hear me?”

She said, “Will it make any difference what I say?”

That stung. “Do you think I don’t care about you?”

“I think you don’t listen. I told you what it’s like, before, but that didn’t change anything.”

There was nothing self-serving in her tone; just a chillingly wary disillusionment. Sam didn’t believe she was trying to manipulate him, spinning him stories out of some childish desire to break the shackles of bedtime. “Tell me again. Tell me how you feel, right now.”

Emma took a while to reply. “I feel like it’s the middle of the night,” she said. “As if someone woke me up and dragged me out of bed, and everyone around me wants to do daytime things, but it’s not the time for all that. And even if I wanted to join in…I can’t! I can’t just pretend and play along with them. I don’t have the energy.”

“So you’re tired?” Sam asked her. “Right now? As if it’s midnight?”

“Yes,” she agreed. “Tired, but not sleepy. That makes it worse. Even if I lie down in bed, I wouldn’t be able to sleep. And I know that when I really want to be reading, or talking to my friends, or playing, the sun will go down and the lights will go out and I’ll fall asleep before I can finish my thoughts that I couldn’t even think before, in the daytime.”

“Okay. I think I understand now.” Sam’s insomnia messed him up, but it always went away in the end. To have your body going through the motions, day after day, while you were trapped inside, never able to bring yourself into synch, would be a kind of torture.

“I’m sorry I didn’t listen to you,” he said.

Emma shrugged wearily. “So what now?”

“I don’t know,” he confessed. “But I’m not giving up; we’re going to fix this. Just let me find a way.”

11

Laura was the first hurdle; Sam couldn’t even think about backing away from the “cure” if he didn’t have her completely on board.

But Laura needed solid evidence; she’d convinced herself that Emma’s testimony alone could never prove anything. Sam was at a loss to imagine how he was meant to prove what none of the labs testing the zeitgeber had even noticed, with all of their expertise and equipment. Then again, they might have been instructed not to look too closely.

It came to him at night, as he stared at the digits of the bedside clock. The idea seemed so simple and right that he closed his eyes and let the afterimage fade, sinking into the darkness, before he could start questioning it. If there were obstacles, he could find them in his dreams.

When he woke, he hadn’t changed his mind. He waited until Laura emerged from the shower, and he explained the plan while she was dressing.

“It sort of makes sense,” she conceded reluctantly.

“That’s not good enough,” he pressed her. “Either you commit to this, or you tell me why you won’t. No going back on what it means after the fact.”

“I can choose the time? Without warning either of you?”

“Yes.” Sam wasn’t sure if she really believed he’d try to cheat and contrive the outcome, but he was happy to banish any opportunity for doubt.

Momentum was building on another front: the older ex-runners were beginning to disappear from his classes, taking their fate into their own hands. Sam wasn’t ready to join them yet, but he’d already had oblique enquiries from some of his ex-colleagues from the runners’ school. Just because they couldn’t use the same building didn’t mean it would be impossible to start again.

Laura bided her time, to the point where Sam began to wonder if she’d lost her nerve and decided to renege. But then, on the fourth night after they’d spoken, she shook him awake.

“You’ve covered the clock,” he observed, amused. She’d also taken his watch from the bedside table.

“That way, you can’t give her any secret signals.”

“Like Clever Hans?” Sam asked mockingly.

“What?”

“The horse that did arithmetic.”

“Don’t start. Are we going to do this?”

They walked together in the dark to Emma’s room, and Laura knelt beside the bed.

“Darling? Can you wake up for me, please?” She touched Emma’s arm and waited for her to respond.

“What is it?” Emma asked. Her voice was thick with sleep; she sounded like any child woken in the night. Sam’s confidence wavered. He’d committed to the experiment as much as Laura; if it failed, he’d have nothing left to argue.

Laura said, “I just want to know, can you tell me…what’s the time in your head?”

Sam felt the darkness tipping. If Emma really was still a runner, in some deep place untouched by the zeitgeber, she would still be on the old schedule. But if it was all a ruse, a bid for attention, she’d have long ago forgotten what she was meant to be feeling, at some unknown hour with no clock in sight.

“Ten past ten,” she replied. “In the morning. And I wish I could get up and go outside, but my legs won’t let me.”

Laura started weeping as she handed Sam his watch. The second row of digits she’d summoned from the app read 10:13 AM. “I’m sorry,” she told Emma. “I’m so sorry!”

Emma said, “It’s all right. But can I please stop taking the pills now?”

Buy the Book

Zeitgeber

“Zeitgeber” copyright © 2019 by Greg Egan

Art copyright © 2019 by Sally Deng