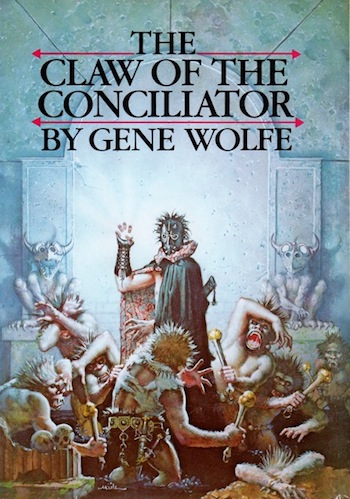

In the previous installment of our reread of The Claw of the Conciliator, we followed Severian (along with his newfound friend, Jonas) into the city of Saltus, where he must perform two executions in his role as carnifex. He had an encounter with the Green Man (who we may meet again, but we won’t be seeing him again in this novel). And he received a note from (apparently) Thecla, only to find out it was actually sent by Agia, luring him into a trap—he then escapes from the trap with the help of the Claw of the Conciliator.

And so we pick up the thread with Severian and Jonas, having returned from the cave, deciding to eat and rest. They then engage in an interesting conversation, during which the two get to know each other better. Severian supposes that Jonas must be an outlander—that is, a foreigner from very far away…maybe even from outside Urth, even though humans do not travel among the stars anymore. He poses three questions to Jonas, mostly about the nature of the man-apes, but also if the soldiers stationed nearby were there to resist Abaia. As I had noted before in relation to Severian’s strange dream at the inn in The Shadow of the Torturer, the gods of the deep are of great interest to Wolfe’s protagonist.

Speaking of water, I thought then (and still do) that Severian’s preoccupation with water (along with his two or more near-drownings) has intensely Catholic overtones, because of its connection with baptism. I also seem to recall (though it may seem really obvious by this point) that the image of Severian drowning will occur a few times before the end of the series. The structure of the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church come to mind now: even though only the first one, the baptism, requires water (often in a baptismal font, where the priest usually pours water on the forehead of the baby), all of the sacraments require some sort of anointing, in most cases with oil. So there is always some immersion of sorts, in a kind of primeval water or liquid that purifies the subject. I’ve decided that I will start counting (from the beginning) the number of times the drowning incidents occur as Severian’s path unfolds.

Jonas provides answers to his companion’s questions and reveals to him (and to us, who are too much used to figures of speech) that Erebus and Abaia are indeed real, not mythological constructs, and that they are indeed giants. As he says:

Their actual size is so great that while they remain on this world they can never leave the water—their own weight would crush them.

Something about this statement is very intriguing: “while they remain on this world,” he says. Are Abaia and Erebus outlanders as well? And, if they came from another world, what world it was? With what purpose did they come? Is it important, after all? We can’t know for sure just yet.

Jonas and Severian go to sleep, only to be visited by strangers who grasp them and take them away. When Severian asks where are they going, one of the men answers cryptically: “To the wild, the home of free men and lovely women.” And he adds: “My master is Vodalus of the Wood.”

But now Severian is not so sure if he is happy to hear this: after all, he executed Barnoch, who might have been a soldier of Vodalus, and if that’s the case, then Vodalus likely won’t be kind to him. In the moment, he reaches an important conclusion:

I saw how little it weighed on the scale of things whether I lived or died, though my life was precious to me.

When he gets there, Vodalus salutes him, saying: “I sent my men to fetch the headsman. I perceive they succeeded.”

To which Severian replies:

Sieur, they have brought you the anti-headsman—there was a time when your own would have rolled on fresh-turned soil if it had not been for me.

A point of significance here: if Severian, as carnifex, can considered a personification of death, to be an anti-headsman would put him in a position of bringer of life—just as the New Sun is supposed to be. One could argue that Wolfe has been pointing us in this direction from the very first scene of the series, even though he shows enough death to us to cloud our vision (as a good magician does).

Vodalus then recognizes Severian from their earlier meeting and makes him a proposition: since he once saved Vodalus’s life, the renegade will in turn spare Severian’s life, as long as he agrees to serves him again in an important task.

In the next chapter, they talk of the past, and the name of this planet is brought up again. As a reader reminded me a while back in the comments, Urth is not just a misspelled word version of “Earth” (though it might be interpreted like this, and I had done so the first time I read the series) but quite another thing, involving (this time I did my homework) the names of the Norns in Norse mythology, even though this particular meaning is not discussed explicitly in the text here). Instead, Vodalus says:

Do you know how your world was renamed, torturer? The dawn-men went to red Verthandi, who was then named War. And because they thought that had an ungracious sound that would keep others from following them, they renamed it, calling it Present. That was a jest in their tongue, for the same word meant Now and The Gift.

(…) Then others—who would have drawn a people to the innermost habitable world for their own reasons- took up the game as well, and called that world Skuld, the World of the Future. Thus our own became Urth, the World of the Past.

A very elegant explanation. Which leaves us with one more question (well…one among many, many): if Earth belongs to the past, will we see Mars (the world of now) or Venus, that, according to Michael Andre-Driussi is Skuld (but I must confess I thought of Mercury, though Wolfe refers to it as the “innermost habitable world,” not the innermost world, period.)? I don’t know, but I seem to recall that Severian will see something of them when he gets off Earth. But we are not quite there yet.

Buy the Book

The Complete Book of the New Sun

They talk about how the human race is greatly diminished in power; Vodalus’s spiel is compelling and also revolutionary. Maybe he wants to restore Urth back to its ancient power? But, even if that’s what he desires to achieve, can he? It is then that Severian feels the urge to confess to Vodalus that he is carrying the Claw. Vodalus has great respect for the artifact, but urges Severian to hide it somewhere, or even to get rid of it if possible. He doesn’t want it, because he knows he will be considered a traitor and desecrator if he is found to be in possession of the Claw.

They are then interrupted by a messenger, and Vodalus disappears. Some time later, Severian and Jonas are led to supper.

This, reader, is one of the most horrible scene in the series. For me, it’s second only to the apparition of the Alzabo (later in the series). The alzabo is a flesh-eating animal, and when it eats someone, it somehow absorbs the memories and abilities of this person—one could easily say that it devours one’s soul, for it suddenly starts to talk as if it were the person it just ate (I still remember that the scene scared me shitless, as much as Harlan Ellison’s I Have no Mouth and I Must Scream). I will probably have more to say about this particular bridge when I cross it.

In The Claw of the Conciliator, though, what happens is this: Severian takes part in a feast during which he eats something that seems to be the roasted flesh of Thecla. How her corpse came to be in the possession of Vodalus, he does not know. The motive is clear: Thecla was sister of Thea, companion of Vodalus, and she certainly asked him to fetch her sister’s body. Explaining the upcoming ritual, Vodalus says:

So we are joined—you and I. So will we both be joined, a few moments hence, to a fellow mortal who will live again—strongly, for a time—in us, by the effluvia pressed from the sweetbreads of one of the filthiest beasts. So blossoms spring from muck.

First they drink each a small dose of what Vodalus tells Severian that is the analeptic alzabo, a kind of elixir that is prepared from a gland at the base of the animal’s skull. They also drink from another bottle, which Thea explains contains a compound of herbs that soothe the stomach.

Here, the old ritual of cannibalism is performed almost as it was documented by Hans Staden in the 16th century, among other accounts: if in early Brazilian history, the young German soldier captured by the tribe of the Tupinambás witnessed them eating the flesh of fallen soldiers in order to gain their strength and courage, the tribe of Vodalus eats Thecla’s body in order to experience and share her memories. Any reasonable doubt we could have about this process vanishes when Severian starts to remember things that he has not lived:

Yet some part of her is with me still; at times I who remember am not Severian but Thecla, as though my mind were a picture framed behind glass, and Thecla stands before that glass and is reflected in it. Too, ever since that night, when I think of her without thinking also of a particular time and place, the Thecla who rises in my imagination stands before a mirror in a shimmering gown of frost-white that scarcely covers her breasts but falls in ever changing cascades below her waist. I see her poised for a moment there; both hands reach up to touch our face.

Then he tells Jonas that they are going to the House Absolute, where they will be able to meet Dorcas and Jolenta, and he will have to undertake a task for Vodalus—even though he has no intention of performing it.

Things, however, won’t happen the way Severian might have wished (does he even know exactly what he wishes, we might ask?). The next day they are riding through a forest when something that at first seems like a great bat “came skimming within a handsbreath of my head.” They started galloping madly and this great bat swoops to attack them again, but Severian catches it with a two-handed stroke of Terminus Est:

It was like cutting air, and I thought the thing too light and tough for even that bitter edge. An instant later it parted like a rag; I felt a brief sensation of warmth, as though the door of an oven had been opened, then soundlessly shut.

Severian wants to dismount to examine the fallen creature, but Jonas seems to know better, and urges him to flee. They make their way out of the forest, entering a broken country of steep hills and ragged cedars.

As with the alzabo (in the future of this narrative), Wolfe works amazingly well at describing strange creatures in bits and pieces, little by little—something that Lovecraft also did well, with all the problems of his convoluted, Victorian-like narrative. I didn’t remember this particular creature from earlier readings, but this whole scene frightened me. The reason is quite simple: I have a particular aversion to creatures without faces, or whose faces I can’t see. And the notules, as Jonas calls them, are so… alien that they can’t be compared to anything but bats, and that only because of their color and their apparent mode of flight.

The embattled companions enter a tangled growth, but they keep hearing a dry rustling. Jonas urges Severian to get out or at least keep moving. He also insists that they must find a fire, or a big animal they can kill—otherwise they will surely die. Severian asks Jonas if it’s blood the creatures want. “No. Heat,” Jonas replies.

Severian rides hard, fighting off the “rags of black,” as he calls the creature, and suddenly, someone appears at the distance. Suddenly enlivened by the prospect of approaching help, Severian raises Terminus Est:

(..) I lifted my sword to Heaven then, to the diminished sun with the worm in his heart; and I called, “His life for mine, New Sun, by your anger and my hope!”

This moment feels closer to the spirit of the Arthurian Cycle than Catholic mythos. Intriguingly, in this scene, Severian feels compelled to speak those words without ever having learned them (or so we are led to believe), moved from his heart like a true knight of old. For this is a medieval novel of sorts—more realistic in style and reminiscent of the classic picaresque, as in Lazarillo de Tormes, for instance. In this 1534 Spanish novel, the eponymous protagonist relates his story to the reader in an epistolary fashion, describing for us the Spanish countryside, where he meets many people from different walks of life and learns many things, most of them mundane, but also a few lessons in religion—for the picaresque story is one of morality.

But even though The Book of the New Sun can definitely be seen as related to the picaresque, there are points in the narrative when we glimpse something of the romantic, in the sense of the revisionist view of knighthood that Sir Walter Scott popularized in Ivanhoe. Other possible influences for Gene Wolfe, both as an author and as a Catholic, is Thomas à Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ, a devotional book from the 15th Century which begins: “Whoever follows Me will not walk into darkness.”

The uhlan (or road patrol) meets this salutation as if it was a war cry, and the blue radiance at the tip of his lance increases as he spurs his horse towards them (the energy weapon being, of course, another reminder that we are in the future).

The creature is now two, and Severian strikes one of the notules again, turning them into three. He tells us he does have a plan, though it’s not completely clear what he is trying to accomplish… The uhlan fires a bolt of energy in his direction, but it strikes a tree instead. We never find out if the bolt is aimed at Severian or at the creatures, or if its goal had always been the tree, calculated to generate enough heat to attract the creatures. Unfortunately, the notules seem to prefer human heat instead: They go for the uhlan’s face, and he falls off his horse.

They approach the fallen rider and find him dead. Jonas knows how to trap the creatures by putting them inside something watertight. He turns out the uhlan’s pockets and finds among his things a brass vasculum (a jar) full of herbs. He empties it and carefully pulls the creatures from the uhlan’s nostrils and mouth, trapping them inside the jar. Then Jonas insists they depart, but Severian thinks otherwise. He draws the Claw out of his boot, and lays it on the uhlan’s forehead, trying for an instant to will him alive.

Jonas scolds him, telling Severian the man is not quite dead, and that they should run before he gets his lance back. Then Severian turns back to the road to see someone indeed approaching; when he looks again at the uhlan, his eyes are open and he is breathing. When Severian takes the Claw from his forehead and puts it back into his boot, the man sits up and asks who is he. “A friend,” he answers.

With the help of Severian, the uhlan gets up, looking very disoriented. Severian explains to the man, whose name is Cornet Mineas, that they are only poor travelers who happened to find him lying down there, for he has no immediate recollection of the past few minutes; he can’t even remember where is he now. So Severian doesn’t tell the uhlan that the Claw has given his life back. It’s an interesting, possibly ambiguous moment, because he is not totally sure that the Claw is responsible for reviving the man, but after the attack of the notules, there was not much to doubt about the man’s death. Or was there?

See you on Thursday, October 31st, for the Part 3 of The Claw of the Conciliator…

Fabio Fernandes started writing in English experimentally in the ‘90s, but only began to publish in this language in 2008, reviewing magazines and books for The Fix, edited by the late lamented Eugie Foster. He’s also written articles and reviews for a number of sites and magazines, including Fantasy Book Critic, Tor.com, The World SF Blog, Strange Horizons, and SF Signal. He’s published short stories in Everyday Weirdness, Kaleidotrope, Perihelion, and the anthologies Steampunk II, The Apex Book of World SF: Vol. 2, Stories for Chip, and POC Destroy Science Fiction. In 2013, Fernandes co-edited with Djibrilal-Ayad the postcolonial original anthology We See a Different Frontier. He’s translated several science fiction and fantasy books from English to Brazilian Portuguese, such as Foundation, 2001, Neuromancer, and Ancillary Justice. In 2018, he translated to English the Brazilian anthology Solarpunk (ed. by Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro) for World Weaver Press. Fabio Fernandes is a graduate of Clarion West, class of 2013.