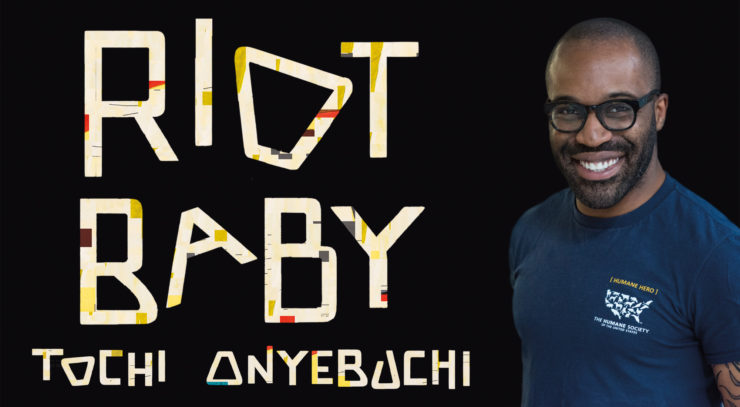

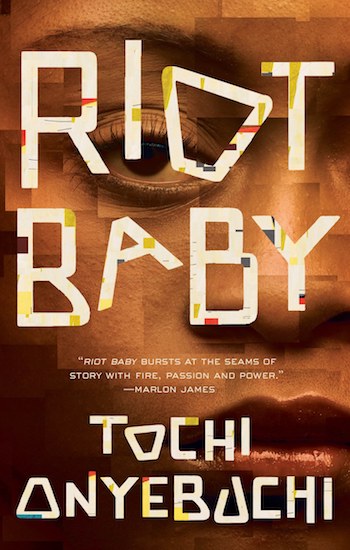

The story of two gifted siblings with extraordinary power whose childhoods are destroyed by structural racism and brutality and whose futures might alter the world, Tochi Onyebuchi’s Riot Baby is a nitrous-fueled novella that pulls no punches—available January 21, 2020 from Tor.com Publishing. We’re thrilled to share an excerpt below!

Ella has a Thing. She sees a classmate grow up to become a caring nurse. A neighbor’s son murdered in a drive-by shooting. Things that haven’t happened yet. Kev, born while Los Angeles burned around them, wants to protect his sister from a power that could destroy her. But when Kev is incarcerated, Ella must decide what it means to watch her brother suffer while holding the ability to wreck cities in her hands.

Rooted in the hope that can live in anger, Riot Baby is as much an intimate family story as a global dystopian narrative. It burns fearlessly toward revolution and has quietly devastating things to say about love, fury, and the black American experience.

Ella and Kev are both shockingly human and immeasurably powerful. Their childhoods are defined and destroyed by racism. Their futures might alter the world.

I

South Central

Before her Thing begins. Before even Kev is born. Before the move to Harlem. Ella on a school bus ambling through a Piru block in Compton and the kids across the aisle from her in blue giggling and throwing up Crip gang signs out the window at the Bloods in the low-rider pulling up alongside the bus. Somebody, a kid-poet, scribbling in a Staples composition notebook, head down, dutiful, praying almost. Two girls in front of Ella clapping their hands together in a faster, more intricate patty-cake, bobbing their heads side to side, smiling crescent moons at each other.

Bus slowing, then stopped. Metallic tapping on the plastic doors, which whoosh open, and warm air whooshes in with the Pirus that stomp up the steps in their red-and-black lumberjack tops with white shirts underneath and their red bandannas in their pockets and their .357 Magnums in their hands, and one of them goes up to the ringleader kid who had been throwing up the signs most fervently and presses the barrel of the gun to his temple and cocks back the hammer and tells the kid to stay in school and if he catches him chucking up another Crip sign, he’s gonna knock his fuckin’ top off, feel me? And Ella can see in the gangbanger’s eyes that he’s got no compunctions about it, that this is only half an act, it’s only half meant to scare the kid away from the corner, that if it came to it, the guy would meet disrespect with murder.

Ella hates South Central. She doesn’t know it yet, but can sense vaguely in a whisper that Harlem and a sweltering apartment and a snowball are somewhere in the distance, not close enough to touch, but close enough to see.

*

Ella calls her Grandma even though she’s not Mama’s mother. Still, she does all the grandma things. Takes Ella to church when Mama’s working or out or passed out on the couch from whatever she was doing the night before. Brings Werther’s chewy candies in the wrinkled gold wrappers whenever she comes by to help out with the chores. Keeps the bangers with their 40s of Olde English at bay when they loiter a little too close to the house and the garden that she protects like it’s her grandchild too. And now Ella’s old enough that she can sit outside on the porch to escape the heat that gets trapped indoors, the heat that turns the plastic covering the couch into a lit stovetop.

Buy the Book

Riot Baby

Grandma sweeps bullet shells out of the empty driveway while Ella chews on her second Werther’s of the afternoon.

Blessing, the pit bull next door, yanks itself against its chain, and Ella shakes her head, as if to say “it’s too hot, I know,” but dogs can’t talk, and this one wouldn’t listen anyway. Still, she remembers Mama telling her not to egg that dog on, not to tease it because one day the chain around its neck and the chain link fence it sometimes throws itself against won’t be enough.

One of the neighbors, LaTonya, walks by holding her baby, Jelani, against her chest, and Grandma stops sweeping and smiles, and LaTonya holds one of Jelani’s wrists and makes him wave at Grandma. “Say hi, Jelani,” LaTonya coos.

“Oooh, he’s so big!” Grandma tells LaTonya, and LaTonya brings him over, hesitating only a moment to acknowledge the pit bull.

“Pretty soon, he’ll be ready for daycare,” LaTonya says, and even from the porch, Ella can see the light twinkling in her eyes.

Grandma smiles wide. “The way you look at that child…”

“I know.” LaTonya shows her teeth when she grins, bounces Jelani a little bit. “Doesn’t look a thing like his daddy, but don’t tell Ty I said that.” And the two women giggle.

“Well, you know Lanie’s getting her business started up soon, so you should stop by. She’s been sticking sticky notes on everything, and she’s been saving up for a playpen. Even talking with the library about getting books for the kids. Lanie says we’ll eventually get a computer set up, so the kids can play their games after school. I don’t know how I feel about them staring at a screen all day, but sometimes it’s best to be indoors.”

“Well, you let me know when it’s up and running. Jelani would love to make some new friends. Ain’t that right, Jello.”

Jelani buries his face in his mother’s chest.

“Oh, he’s so shy.”

The sun feels too bright outside like it’s washing the color out of everything, and dizziness hits Ella like a brick. Grandma and LaTonya are still talking when Ella staggers to her feet and stumbles inside, and the light falls in rectangles through the burglar bars over the windows. In the bathroom, she stands over the sink and lets the blood slide a little bit from her nose before tilting her head back up. It always feels like something’s rumbling whenever she gets the nosebleeds, like the earth is gathering itself up under her, but whenever they stop, the nosebleeds, and she looks around, it’s like nobody else noticed a thing. Vertigo pitches her forward. She leans on the sink, squeezes her eyes shut and tries not to think of what she saw outside: the boy named Jelani, grown to ten years old, walking the five blocks home from school, a bounce in his walk and his eyes big and brown before a low-rider screeches nearby and a man with a blue bandana over his face levels a shotgun out the window at someone standing behind Jelani and, after the bang, everyone scatters, leaving Jelani on the ground, staring up at the too-bright sun for the last, longest two minutes of his life.

Grandma finds Ella on the floor, gasping in a long, aching wheeze, then another, then another.

“Oh, Jesus,” and suddenly, she’s at Ella’s side and has the child’s face buried in her chest and rocks her back and forth, even as Ella grows limp. “Oh, Jesus, Jesus, Jesus. Spare this child.”

And Ella’s breath slows, and she comes to. “One Mississippi,” she whispers.

“What?”

“Two Mississippi.”

“Child, what are you doing?”

“Three Mississippi.” A breath. A normal one, then a heavy sigh. “Mama says, when I get my panic attacks to count my Mississippis until it goes away.”

Grandma sounds surprised when she laughs.

*

“Good morning, Junior Church!”

As tall as Brother Harvey is, his suit always seems too big for him. Too many buttons. But it never falls off, no matter how much Ella and Kiana and Jahnae giggle at him. None of the helpers down here in the church basement wear the white gloves the ushers upstairs in the grown-ups’ service wear, so Ella can sometimes see the tattoos on their hands. Brother Harvey moves back and forth in the little row of colored light thrown there by the stained-glass windows with orchids etched into them.

“How many of you pray?” he asks in his too-big voice. He sounds like God.

Ella raises her hand.

“How many of you pray every day?” She puts her hand down. Jahnae keeps hers up, but Ella knows she’s lying.

“You don’t pray every day,” she hisses. Jahnae cuts her eyes at her for a second, but keeps her hand up.

“How many of you do things that are wrong?”

Ella remembers that time she lied about putting her clothes in the wash and, instead, stuffed them into the closet she was supposed to hide in whenever bangers congregated in the alley behind the house. And she puts her hand up.

“God says,” Brother Harvey booms, “‘If you do things wrong and come to me, I’ll forgive you.’” He walks over to Kaylen, the little boy three down from Ella with suspenders and a clip-on tie. Brother Harvey’s hand rises like he’s going to hit him. “If I hit Kaylen here, what is he supposed to do?”

“Forgive you,” all the kids shout, except Ella.

“That means Kaylen’s not supposed to hit me back, right?”

Ella wonders what she would do if Brother Harvey hit Kaylen with that too-big hand of his.

“Now, I’m not saying Kaylen shouldn’t defend himself.” He puts his hand to Kaylen’s head, cups it. “Kaylen, you say, ‘Brother Harvey, I will defend myself, and then at an appropriate time, I will forgive you. And I will do both of these things vigorously.’”

The air starts to change the same way it does whenever Ella catches herself daydreaming, imagining. And she sees an older Kaylen, filled out and all man, working in a hospital as an orderly, and all his patients are old, way older than him, and over and over, the old patients, when they get slow and know it’s not going to be too long now, ask him to sit with them. No bang, no blue bandanna, no pool of blood on the sidewalk. Reflexively, she grips the tissues in the pocket of her frilly dress. She’s up in the front, and a nosebleed now would embarrass her in front of everybody. But it never comes, and she lets go of the tissues and pretty soon they’re singing. Brother Harvey says a prayer for all of them, anointing them; then he sends them back out to their parents or grandparents or people who act like their parents because they need to.

Ella’s so tiny that when the ladies crowd around her, their big hats come together like pink flower tops to hide her from the sun.

*

Mama has Ella’s hand in hers as they walk to the bus stop. Ella skips over the cracks where weeds poke through, more of Grandma’s Werther’s in her pocket. Jahnae will be waiting for them. When Ella looks up, though, Mama’s face is drawn tight, and quiet. Her stomach has grown so big that every step is deliberate. And this is what happens to you when you get pregnant, Ella realizes. You can’t skip no more.

“Mama?”

“Oh,” she says, like she’s been sleepwalking.

“Mama, you okay?”

“Yeah, honey. Just… I got a lot to do today, that’s all. Setting up for the daycare.” Then she grows silent.

“It’s okay, Mama. I daydream too.”

“Do you, now?”

“Mmhmm.” A pause. “But when I do, they’re usually sad. Sometimes, they’re happy like with Kaylen, but most of the time, they’re sad.” She stops skipping, but still watches out for the cracks. “I see bad things happening to the boys. Like, Jelani getting shot. And after Lesane turns ten, Crips are gonna ask him what set he’s from and even though his mama’s gonna teach him to say he doesn’t bang, it’s not gonna—ow!”

Mama wakes up again and stops, almost like she’s just now noticing how hard she’s been squeezing her daughter’s hand. “Oh, baby, I’m so sorry,” she says, kneeling, but Ella’s crying by now, wiping her face with the back of her hand.

“Mama, you hurt me!”

“I know. I’m so sorry, baby,” and she hugs Ella close to her bulging stomach. “I’m so sorry,” she whispers into her pigtails.

“I hate it here.”

Mama blinks.

“I hate it here. Everything’s so—” She searches for a word that will tell Mama how violent it always is or how much she hates having to hide in the closet every time it even looks like gangbangers might roll through, how she hates having to already know what it means to live in Hoover territory, how she almost always imagines horrible things happening to the boys here and how she can’t imagine anything else anymore, a word that will describe the pit that sits in her stomach all the time and the way the ground rumbles beneath her every time she gets a nosebleed like it’s going to open its mouth and swallow everything. “It’s so bad here,” she whimpers.

“Oh, baby.” A look of helplessness flits across Mama’s face. Desperation, then it passes, and Ella already knows it’s because Mama knows she can’t let Ella see her hopeless, and Ella hates that she has to know that. “Baby, that’s just the Devil at work. But you know there’s more out there than just the Devil.”

“But everything’s the Devil!”

“The Devil is busy here.” Mama has taken to smoothing out Ella’s outfit, running her hand down her sleeves. “The gangs, the drugs, all the evil that men do to each other here. Sometimes even the police. That’s the Devil. But you just gotta pray, all right, Ella?”

Ella nods her head.

“Here, baby. Let’s pray, right here.”

“Do I gotta get on my knees?”

Mama chuckles. “No, baby, just gotta stand right here. Just bow your head and close your eyes.”

Ella obeys, and Mama’s voice comes to her hushed and strong.

“Dear Blessed Redeemer. Please protect my baby, Ella, in these trying times. Please surround her in your hedge of protection. Please bless us with food and work, so that we may be healthy and do your will. Please, Lord, cast the Devil out from here, make for us a safe place and grant us mercy on our journey. I pray, Lord, for the little boys that grow up in this world, that you will shield them, and that you will guide them in your ways, that you will build them into big, strong tools for your work. And that whatever you would have us do, you will make the path clear for us. Lord, bless my Ella. Make her strong. Make her smart. Make her powerful. You are husband to the widowed and you are father to the fatherless. And when you are done with us in this world, when you are done with this world, we know you are preparing a better one for us. In your name we pray.”

“Amen.” Ella smiles and wants to tell Mama that while Mama was praying, Ella was saying her own prayer. And she thinks Mama would be proud to hear it. But, soon enough, they get to the corner where Jahnae is waiting, and Mama lets her go.

“Be safe, baby!” Mama shouts as the bus pulls up. “Grandma will pick you up today.”

Jahnae climbs up the steps in front of her, and they settle onto a seat, Jahnae by the window and Ella next to her, looking through it as her mother recedes into the distance. “After she’s born,” Jahnae says, “your sister’s gonna start stealing your clothes. Watch.”

“Mama ain’t having a girl.”

“How you know?”

Same way I know LaTonya’s baby’s gonna get shot in a drive-by when he grows up. Same way I know Kaylen’s gonna work in a hospital and be kind to old white people. Same way I know something horrible’s gonna happen soon, Ella wants to tell her. “Grandma can’t keep a secret,” she says instead.

*

“Hi, Mrs. Jones,” a bunch of her classmates shout as they rush past and form their groups and start heading home. Grandma waves at all of them in small sweeps, smiling her love at them.

“You ready?” she asks Ella.

Ella nods, and they walk into the quiet that blankets the neighborhood after the kids have all spilled out of the schools and some of the teachers hang around out front to whisper worriedly. About King somebody or Somebody King.

“Grandma?” Ella kicks a pebble that zigs one way then zags another, bouncing along ridges in the broken sidewalk.

“Mmm?”

“How come everybody’s always fighting?”

“What do you mean?”

Ella shrugs, not quite sure how to make the words fit what she’s always seeing in her head, what always immediately precedes and follows her nosebleeds. “I mean, the gangbangin’. How come everybody’s always dying so much? They’re always so… angry.”

Grandma’s flats shuffle against the concrete.

“Mama says it’s devilment. It’s the Devil that makes everyone so angry.”

Grandma’s brow creases in a frown, and Ella wonders if Grandma’s forgotten about her because she’s got this far-away look in her eyes, and it looks sometimes like how Mama stares out, not looking at anything really but seeing something Ella can’t see. “They’re not angry at each other,” Grandma says finally. “Not really.”

“Then what are they angry at?” She balls her hands into a fist like whenever she gets close to figuring out a spot in her multiplication table but isn’t quite there yet. “Does it have to do with Rodney King?”

Grandma’s foot catches, but then she rights herself. “What you know about Rodney King?”

“I saw some of my teachers watching the video. How the police beat him.”

Grandma says nothing.

Ella tugs on her sleeve. “Grandma, something bad’s gonna happen.”

“God’s will is the only thing that’s gonna happen.”

They round a corner and find a group of boys outside the Pay-Less Liquor on Florence. There’s shouting going on inside and things breaking, and before Ella can get a good look at whether or not anyone’s wearing gang rags, Grandma pulls her the other way.

“But Grandma, home’s that way.”

“It’s not safe,” Grandma says, breathlessly, as she pulls Ella to move faster.

Ella hears the glass of the front door to the liquor store shatter and she hurries ahead of Grandma.

But further down Florence, they stop. All of a sudden, the air grows hot. It’s like the quiet from earlier was hiding something. Ella’s heart sinks. The ground is going to come up and swallow us, she realizes. Already, at Florence and Halldale, two dozen LAPD officers are forcing a boy into the back of a patrol car as a mass of spectators rumbles toward them.

“Seandel!” someone in the surging crowd calls out. They move like a wave toward the cops. “Seandel!” And terror spikes through Ella’s heart. Somebody in the thick of it pulls out a camcorder and hunches his back to start filming.

Ella looks over her shoulder again as she runs with Grandma, and she sees the tsunami of black folks swarm toward the officers, and she wants to be home more than anything else in the world.

Car wheels squeal and rubber burns nearby and a familiar voice shouts from out a window, “Ella! Mrs. Jones!”

Brother Harvey. Sweat beads his brow and darkens the collar of his button-down shirt, and his suspenders are loose and his shirtsleeves rolled up, but something firms up in him at the sight of Ella and the elderly woman walking her home.

“Hey! Get inside!”

And it’s almost as though Grandma whisks Ella away in her arms, and car doors fly open then slam shut and Brother Harvey is speeding off again with Ella in the backseat and Grandma in the front.

“We gotta get to the hospital. It’s Lanie.”

“Oh no, Steven. Please tell me she ain’t get caught in this.” Grandma’s voice loses its straightness, starts to warble.

“No, it’s her contractions. The baby’s coming.”

Ella in the backseat wants to say something, but she’s balled up like the fetus in Mama’s belly, her skin on fire and her head a-thunder, and she can barely speak for the pain, can barely hear anything through it. The smash of glass bottles breaking, the sound of gunshots, the crackle of fire, the honking of horns, the cheers, the wails, all of it comes through muffled by the pain cotton-ing her ears. The bad thing is happening. It’s happening, because Mama’s gonna have a boy, and she’s gonna have it here, and when Ella starts crying and Grandma reaches back to soothe her, anger wraps itself around her, and she wants to shake off Grandma’s hand and tell her she’s not crying because she’s scared, she’s crying because she’s angry.

“Steven, what happened? What’s going on?”

For a long time, he’s silent. The hurt that has its jaws around Ella’s temples lifts just enough for her to hear him say, “Those cops got off. They ain’t gonna go to jail for what they did,” and for Grandma to whisper, “God in heaven.”

She counts her Mississippis, struggles past four, doesn’t get to six.

She passes out and doesn’t wake until they bring her to Mama’s room at Centinela Hospital in Inglewood.

*

It’s Monday when they finally leave the hospital, and some of the people leaving with them come out, injured and maimed by what happened, to find what Ella and Mama and Brother Harvey and Grandma and now Kev find. Everything has been burned down.

Excerpted from Riot Baby, copyright © 2019 by Tochi Onyebuchi