Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

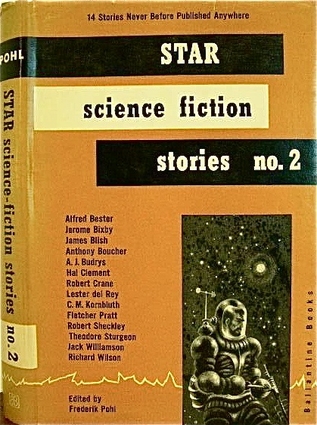

This week, we’re reading Jerome Bixby’s “It’s a Good Life,” first published in 1953 in Star Science Fiction Stories #2, edited by Frederik Pohl. Spoilers ahead.

“Oh, don’t say that, Miss Amy… it’s fine, just fine. A real good day!”

Peaksville, Ohio (population 46) is a good little town, broiling under a too-hot afternoon “sun”—but it’s still a good day, as is every day in Peaksville. Three-year-old Anthony Fremont sits on his front lawn, playing with (torturing) a rat he captured in the basement by making it think it smelled delicious cheese. Aunt Amy rocks on the porch. Bill Soames bikes over to deliver groceries. Like most folks, he mumbles nonsense to keep Anthony from reading his mind. Say you’re thinking too loudly about a problem, and say Anthony likes you and tries to fix the problem. Well, you can’t expect him to know what’s best to do, and things might turn out badly.

If Anthony doesn’t like you, things might turn out even worse.

Aunt Amy doesn’t always remember how to behave around Anthony—a year ago, she chastised him for turning the cat into a cat rug, and he snapped at her with his mind, and ever since Amy’s been a little vague. Today she complains of the heat, forcing Bill to insist that no, it’s fine. Bill pedals off, wishing he could pedal even faster. Catching his desire, Anthony sends a sulky thought that makes the bike pedal Bill, terrifyingly fast.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Amy goes out back to keep Anthony’s mom company while she shells peas. It’s television night that evening, so of course everyone’s coming. It’s also a surprise birthday party for Dan Hollis. Dan collects records; no doubt he’ll be delighted to receive a new one, Perry Como singing “You Are My Sunshine.” New things don’t turn up every day in Peaksville. One day there may be no new things at all.

Anthony walks through the cornfield to his special spot, a shady grove with a spring and pool. Animals flock to it because Anthony provides them with whatever they need. He likes basking in their simple thoughts, their simple gratification. People’s thoughts are much more complicated and confusing and sometimes bad. One animal at the pool has a bad thought, too, about hurting a smaller animal. Anthony thinks the bigger animal into a grave in the cornfield, which is where his father suggested he should put the things he makes dead.

He remembers how some people once had very bad thoughts about him. They hid and waited for him to come back from the grove, so he had to think them into the cornfield too. Since then, no one’s thought that way about him, at least not very clearly. Anthony likes to help people, but it’s not as gratifying as helping animals. People never think happy thoughts when he does, just a jumble.

Anthony doesn’t feel like walking home, so he thinks himself there, into the cool basement where he plays with another rat until it needs a cornfield grave. Aunt Amy hates rats, and he likes Aunt Amy best. Nowadays she thinks more like the animals, and never thinks bad things about him.

He takes a nap in preparation for television night. He first thought some television for Aunt Amy, and now everyone comes to watch. Anthony likes the attention.

The townspeople gather for Dan’s surprise party. Their lives haven’t been easy since Anthony turned everything beyond the boundaries of Peaksville into gray nothingness. Cut off from the world, they must grow all their food and make all their goods. Farming’s the more difficult because Anthony is whimsical about the weather, but there’s no correcting him. Besides, everything’s fine as is. It has to be, because any changes could be so terribly much worse.

Dan’s delighted with his record, though disappointed he can’t play it on the Fremonts’ gramophone—Anthony abhors singing, preferring Pat Reilly to play the piano. Once someone sang along, and Anthony did something that insured no one ever sang again.

All goes smoothly until homemade wine and a precious bottle of pre-Anthony brandy are produced. Dan gets drunk and complains about his not-to-be-played record. He sings “Happy Birthday” to himself. His wife Ethel screams for him to stop. Men restrain her. Irrepressible, Dan condemns the Fremonts for having Anthony. (Later, Mom will think about how Doc Bates tried to kill Anthony when he was born, how Anthony whined and took Peaksville somewhere. Or destroyed the rest of the world, no one knows which…)

Dan starts singing “You Are My Sunshine.” Anthony pops into the room. “Bad man,” he says. Then he thinks Dan “into something like nothing anyone would have believed possible,” before sending him to the cornfield.

Everyone declares Dan’s death a good thing. All adjourn to watch television. They don’t turn on the set—there’s no electricity. But Anthony produces “twisting, writhing shapes on the screen.” No one understands the “shows,” but only Amy dare suggest that real TV was better. Everyone shushes her. They mumble and watch Anthony’s “shows” far into the night, even newly widowed Ethel.

The next day comes snow and the death of half Peaksville’s crops—but still, “it was a good day.”

What’s Cyclopean: The word of the day is “good.” Bixby manages to make it scarier than all Lovecraft’s multisyllabic descriptors put together.

The Degenerate Dutch: The residents of Peaksville appear to have put aside any preexisting in-group/out-group distinctions in favor of the Anthony/Everybody Else distinction.

Mythos Making: Sometimes the incomprehensible entity tearing apart the very structure of reality is an elder god or an alien from beyond the physics we know. And sometimes it’s a three-year-old.

Libronomicon: There are a limited number of books in Peaksville, circulating among the households along with other precious objects. Dad is particularly enamored of a collection of detective stories, which he didn’t get to finish before passing it on to the Reillys.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Honestly, under the circumstances, it’s kind of a miracle the townsfolk don’t have panic attacks and Hollis-style breakdowns more often.

Anne’s Commentary

I first encountered Jerome Bixby’s work on those special “television nights” when I was allowed to stay up and watch the original Star Trek series. He wrote four episodes; my favorite was “Mirror, Mirror,” in which a transporter accident sent Kirk and party to a parallel evil universe, while their evil counterparts ended up on the good Enterprise. You could tell the evil universe was evil because everyone threw Nazi-like hand salutes and Spock had a devilish beard. Also the female crewmembers not only wore miniskirts but also bared their midriffs—okay, that’s sexualizing female crewmembers too far. Only an evil Federation would do that. Or Gene Roddenberry, dodging as many network decency standards as possible.

I first encountered “It’s a Good Life” in its original Twilight Zone version. Rod Serling’s teleplay wisely sticks close to Bixby’s story. My biggest disappointment is that Anthony turns Dan Hollis into a jack-in-the-box, which is simply not “something like nothing anyone would have believed possible.” I picture Dan’s transformation as more Mythosian, think Wilbur Whateley exposed and bubbling into dissolution. But those special effects would have broken Serling’s budget. Or maybe jack-in-the-boxes were his phobia? Anyhow, it’s hard to capture the unimaginably terrible in image. It’s hard to do in words, too, which is why Bixby lets us conjure Dan’s punishment for ourselves.

The second “Good Life” adaptation came in the Twilight Zone movie, in the segment directed by Joe Dante from Richard Matheson’s screenplay. This version retains Bixby’s elements while veering far from his details and overall “feel.” It introduces schoolteacher Helen Foley, who meets Anthony on a cross-country trip. He takes her home to his unnaturally cheerful family, actually strangers he’s kidnapped to take the place of his (killed-off) relatives. They warn Helen she’ll suffer the same fate. Anthony-directed hijinks ensue, such as one “relative” ending up in a television cartoon, devoured by a cartoon monster. But Helen’s used to naughty children. She makes a deal with really-only-misunderstood Anthony: She’ll never leave him if he’ll accept her as his teacher. As they drive off together, fields of flowers spring up in their wake. Aww, so heartwarming. So not Bixby’s truly and deeply terrifying tale.

We adults (or reasonable facsimiles thereof) know children can be little monsters of ego and willfulness. Being selfish is part of developing a self—it’s the adults’ job (being bigger and hopefully smarter) to curb excesses. But what if children had the power to fully express their natural impulses? To act on their insecurities and misunderstandings? To render their fantasies real? Are we talking horror now? Yes, we are, and Bixby’s “Good Life” is arguably the most chilling take on the nightmare premise of an all-powerful child, a God-Kid.

Lovecraft frequently deals with the idea of children misbegotten: Dunwichian or Martensian products of incest and inbreeding, or interracial/interspecies hybrids like the Jermyn half-apes and the Innsmouth-Lookers. The closest he comes to a menacing God-Kid may be Azathoth, who never grows beyond the seething and mindless stage and who maddens all with the obscene whine of his amorphous pipers, the Azathothian equivalent of “Baby Shark.”

I think Anthony Fremont would’ve scared Howard to conniptions. At least Howard could explain why his misbegotten children were weird—look at their parents! Bixby’s monster child comes from normal folk. Hypernormal folk, in fact, salt-of-the-earth small-town Ohioans! He’s a random mutation. Phenotypically he may be normal, except for those unnerving purple eyes. Note that Bixby doesn’t call Anthony’s eyes violet or lilac or any other “softer” shade of the red-blue combination. Just purple, the color of bruises.

Maybe Anthony has “marks of the beast” beyond his eyes. What made Doc Bates try to kill him at birth? When Anthony’s mother remembers how he “crept from her womb,” is that metaphor or reptilian reality?

Bixby’s language is masterfully suggestive throughout “Good Life,” interspersed with judicious bits of nastiness like Anthony making his rat-victim eat itself. Masterful, too, is how he combines the page-one revelation of Anthony’s mental powers with the gradual unfolding of how those powers have affected Peaksville. It’s not the sun that makes Bill Soames sweat, but an unnatural “sun” of Anthony’s making. The town’s isolation unfolds as Amy handles Mason jars from the grocery rather than commercial tins, beet sugar rather than cane, coarse (crudely ground) flour rather than fine. The townspeople must now struggle to grow or make everything themselves. “New” (actually refound and reappreciated) things have become inestimably valuable.

The bulk of Bixby’s narration is omniscient, but he includes a crucial passage in Anthony’s point-of-view. By examining the God-Kid’s thoughts and emotions, Bixby allows the reader to sympathize with Anthony and to realize he’s not a psychopath, just a child with the ability to do whatever the hell he wants, screw adult interference. He’s amoral, not evil. He’s confused, able to sense other’s thoughts of violence or displeasure as bad without knowing how to gauge the potential danger to himself. Too young to reflect, he reacts.

Anthony’s no monster, just a normal human kid with supernormal brain circuitry. That he fills cornfields with corpses and may have destroyed the whole world beyond Peaksville, ah, therein lies the enduring power of “It’s a Good Life” to horrify.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I first encountered “It’s a Good Life” in my ratty second-hand copy of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame at 11 or 12. It was one of my favorites in the collection, and I read it regularly until I went to college and actually started to like people. At this point it’s been a couple of decades, and I approached with some trepidation, afraid that I’d forgotten some detail that would ruin the whole thing—or that my own transformation from bullied kid to anxious parent would make reading it a misery.

Nope. This remains one of the most perfectly terrifying stories I’ve ever read.

Being a parent does add new layers to the terror. Much of raising kids involves instilling the idea that the world exists separately from their desires, and that other people have needs and choices that matter just as much as their own. This is a long-term project even when all evidence and the laws of physics are on your side—I’ve had to remind my own kids several times this week. Anthony probably started out no more solipsistic or selfish than most infants, but that’s a high bar. And a kid you can’t teach or discipline, but who can see every moment of fear and exhausted frustration that goes through your head…

Honestly, it’s a miracle anyone survived him learning to sleep through the night.

Most kids, like Anthony, also go through bouts of unhelpful helping. Mine are more inclined to sharing favorite dinosaur toys with sick dogs, but I don’t want to think about what they’d try if they had telekinesis and matter control. The scene in the clearing is particularly sharp—we see the degree to which Anthony genuinely wants to help, and wants to have whatever he’s helping be grateful rather than terrified. We see why he appreciates animal simplicity. And we see that even under ideal circumstances, he still does harm.

The other new thing I picked up, this time around, is the degree to which the story distills the all-too-real experience of abuse. The unpredictability, the isolation from any source of aid, the urgency of hiding anger or fear or sadness—especially in reaction to the abuser—are all too real for all too many. After all, someone doesn’t need to be omnipotent to have power over you.

At the same time, the story hits the perfect center of gravity between relatable horrors and horrors beyond human comprehension. Because Anthony may be what happens when you give an ordinary infant vast cosmic power—but he also has the eldritch abomination nature. Something incomprehensible appears in the midst of ordinary life, destroying, maybe not even aware of how its actions impact you and certainly not interested in you as an independent entity. Give him a few aeons and a cosmic void to play with (and there is indeed a cosmic void convenient to hand), and Anthony might grow up to be Azathoth.

Which raises the question of how human Anthony really is. Even country doctors in the ’50s were not, I think, inclined to murder infants because they had weird-colored eyes. And Bates tries to kill Anthony before the kid does the thing. Is his power obvious even when he’s not using it? What was so obviously wrong in that first moment?

And would he have turned out differently if the first person he met hadn’t responded with homicidal terror? Does he have any potential to do better even now? Despite the vast challenges involved in trying to instill ethics and empathy in such a creature (see above), my inner 12-year-old—who kind of wondered whether Carrie White might make a decent Anthony-sitter—keeps trying to think of a way.

Next week, we continue the creepy kids theme with Shirley Jackson’s “The Witch.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.