The Age of Revolutions has always fascinated me. After I first learned about the French Revolution as a child, I promptly decapitated my Princess Jasmine Barbie for crimes against the Republic. (My mother screwed her head back on, thus allowing Princess Jasmine to elude revolutionary justice.) This time period, roughly 1774-1849, encompasses some of the greatest shifts in Western thinking, and transformations of Europe and its colonies so seismic that, when asked about the influence of the French Revolution, former Chinese premier Zhou Enlai is purported to have replied, “It’s too early to say1 .”

But for all these dramatic changes, these great increases of rights for the common man and citizen, the expanded world of the age of sail, it is one of the most whitewashed periods of history in contemporary culture. Period pieces—and the fantasies inspired by them—are pale as debutant’s white muslin gown. In the days before Hamilton suggested that people of color could own and be interested in the American Revolution as much as white students, I had the same historical vision of this time period as a 1950s Republican Senator. I had a vague understanding that the Indian muslins and Chinese silks Jane Austen characters wore had to come from somewhere, but someone like me, a mixed race kid with a Chinese mother and a white American father? I didn’t belong there. There was no place for me in this history.

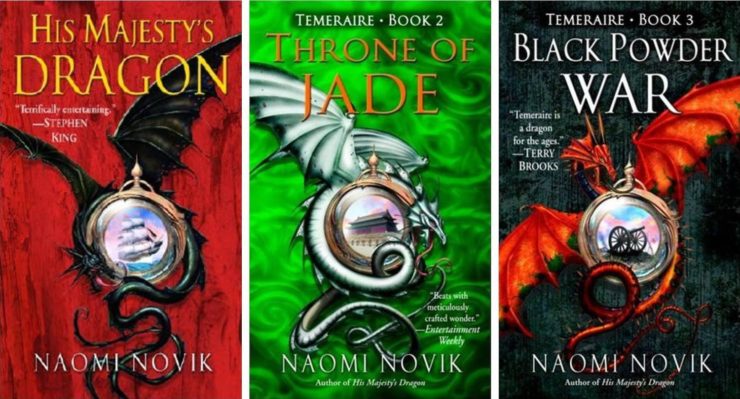

Enter Tenzing Tharkay, from Naomi Novik’s alternate history Temeraire series.

And he has an amazing entrance in Black Powder War:

[A Chinese servant] was gently but with complete firmness being pressed aside by another Oriental man, dressed in a padded jacket and a round, domed hat rising above a thick roll of dark wool’ the stranger’s clothing was dusty and stained yellow in paces, and not much like the usual native dress, and on his gauntleted hand perched an angry-looking eagle, brown and golden feathers ruffled up and a yellow eye glaring; it clacked its beak and shifted its perch uneasily, great talons puncturing the heavy block of padding.

When they had stared at him and he at them in turn, the stranger further astonished the room by saying, in pure drawing-room accents, “I beg your pardon, gentlemen, for interrupting your dinner; my errand cannot wait. Is Captain William Laurence here?”

The Temeraire series poses the question, “What if the Napoleonic Wars included dragons?” and then sends its heroes careening across the globe to see how the introduction of dragons has changed each country and the worldwide balance of power. Black Powder War sees British Captain William Laurence, his Chinese dragon Temeraire, and his British crew end a diplomatic mission in China and head to Istanbul to pick up three dragon eggs purchased by the British government from the Ottoman Empire. Tharkay, their guide to Istanbul across Central Asia, is half-Nepalese, half-white, and all sarcastic humor. I instantly loved him. I had never before seen another half-Asian person in anything set during the Age of Revolutions. He provided, as I joked to another Asian-American friend of mine, a sort of “cravat identification,” where for the first time I could see where I might fit into the time period I so loved to read about. Tharkay even points out the “endless slights and whispers not quite hidden behind my back,” he endures from white Britons, and explains that he prefers to provoke it, finding it easier to live with “a little open suspicion, freely expressed, than [to] meekly endure” an onslaught of microaggressions so very close to the ones I well knew. Tharkay is particularly bitter about the distrust with which white, British society views him, and so decides to provoke it, and pull it out into the open. When asked if he likes to be doubted, Tharkay replies, “You may say rather, that I like to know if I am doubted; and you will not be far wrong.”

To be mixed race Asian and white—in my own personal experience, with all the gendered, temporal, and class-based differences implied—is to exist in a state of continual distrust, but continual ambiguity. When “What are you?” is at the top of your FAQs, it’s difficult not to engage with the existential uncertainty it implies. Certainly, some people distrust your answer as soon as you give it, but it is less a matter of someone assuming you are untrustworthy, than someone paternalistically assuming they know who you are better than you know yourself. For me, at least, mixed race identity is a tightrope act balanced on the hyphen of your demographic information, when it isn’t some kind of Zen koan. Are you Asian, or are you American? Are you both, or neither, or some of each, or something else entirely?

The pandemic has me thinking differently about Tharkay’s response. As John Cho recently pointed out, Asian-American belonging is conditional. The doubt that Tharkay deliberately provokes does exist—just in a different form than Novik presents in Black Powder War. It is less that people of Asian descent can’t be trusted to do a job, or be a gentleman, or follow through on an oath. There is, instead, a pervasive doubt that you will ever be American, or British—that because of the body you happen to inhabit, you can belong or be loyal to any country other than the one that helped shape your genomes generations ago.

Buy the Book

Burning Roses

The nearly-but-not-quite match of the fictional Tharkay’s experience to my own caused me to dig deeper into the real history of Regency England, in search of other Asian people.

I didn’t have very far to dig. Even when one relies on sailcloth and oak alone to traverse the globe, people of color existed, and traveled, and interacted with Western Europeans—a fact I felt quite stupid not to have realized before. Regency London had massive Black and Jewish populations, Rromani people had traversed the English countryside for centuries, and the East India Company hired so many Lascar (Southeast Asian) and Chinese sailors, they contracted a Chinese sailor, John Anthony, and his British in-laws to help create a barracks to house these sailors in the East End of London. Antony himself is a fascinating figure. He appears in Old Bailey records as an interpreter for Chinese and Indian sailors, had been a sailor since the age of eleven, and had chosen to settle in England “since the American War.” He made a permanent home in England, marrying an English woman and eventually amassing so large a fortune he bought an estate in Essex. In 1805, he became the first person born in China to become a naturalized citizen through an Act of Parliament.

It shouldn’t have surprised me as much as it did, to know that people of color always existed. They had just been deliberately and purposefully excluded from the stories we now tell ourselves about the past. Knowing that also clarified, for me, just why I had been so drawn to the Age of Revolutions in the first place. A true happy ending for me, and for many who live within power structures built on their labor, yet also built to exclude them and erase them from the historical record, is revolution. It is not joining the order at the top of the pile and lording it over all those who sought to exclude you; it’s shoving the pile over entirely. Hegemony cannot bring happiness.

As Rousseau wrote, towards the beginning of the Age of Revolution, “Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.” Western Europe and its colonies all grappled with this understanding, this particular way of characterizing society, and, imperfectly and strangely and often with baffling intolerance for others in chains, it began to break the shackles on each citizen. It overturned the crushing constraints of late stage feudalism; it began the long and lengthy struggle for abolition. In this time period I see my own struggles writ large, and thanks to Tenzing Tharkay, I at last saw my place in it.

Elyse Martin is a Chinese-American Smith College graduate who lives in Washington DC with her husband and two cats. She writes reviews for Publisher’s Weekly, and her essays and humor pieces have appeared in The Toast, Electric Literature, Perspectives on History, The Bias, Entropy Magazine, and Smithsonian Magazine. She spends most of her time writing and making atrocious puns—sometimes simultaneously—and tweets @champs_elyse. She’s at work on several novels.

[1]He may, however, have been talking about the 1968 student revolution.

London’s had curry restaurants since the mid 18th century, but the first one to be owned and run by an Indian was opened in 1810. Sake Dean Mohamed also did deliveries:

Sake Dean Mahomed, manufacturer of the real currie powder, takes the earliest opportunity to inform the nobility and gentry, that he has, under the patronage of the first men of quality who have resided in India, established at his house, 34 George Street, Portman Square, the Hindoostane Dinner and Hooka Smoking Club.

Apartments are fitted up for their entertainment in the Eastern style, where dinners, composed of genuine Hindoostane dishes, are served up at the shortest notice… Such ladies and gentlemen as may desirous of having India Dinners dressed and sent to their own houses will be punctually attended to by giving previous notice…

I’d like to give a shout-out to the French Revolution, a critical event that most Americans know far too little about.

In the course of a few short years, the French Revolution:

1. Established universal manhood suffrage.

2. Redistributed land from wealthy landowners to farmers.

3. Abolished slavery.

Of course they also

4. Murdered each other until the Revolutionary government collapsed and was replaced by an incompetent caretaker government, which was then usurped by Napoleon.

It’s an interesting study in different approaches to change; America had a relatively conservative, careful revolution that didn’t try to go too fast, and we avoided much of the fratricide and bloodshed of the French Revolution.

We also avoided radical change towards a more egalitarian society, and that bill came due ninety years later.

It turns out that changing the world is hard, and there’s no way to get it right. But we should all take a moment to remember the fanatics who looked at the world they lived in and said “No”. They should never be spared from criticism or exempted from blame, but we wouldn’t be having these conversations without the work of horribly flawed people who tried to leave the world better than they found it.

the French Revolution: …

3. Abolished slavery.

For all of eight years (and in practice only in some of the colonies, not all), until Napoleon restored it. Lasting abolition had to wait until 1848.

Of course they also

4. Murdered each other until the Revolutionary government collapsed and was replaced by an incompetent caretaker government, which was then usurped by Napoleon.

That’s selling them a bit short. I’d add:

5. Caused the death of over 100,000 people in the suppression of the Vendee Rebellion.

6. Helped cause the deaths of probably a million people throughout Europe during the French Revolutionary Wars — or something like 3 million deaths if you include the Napoleonic Wars that came immediately afterwards.

“When “What are you?” is at the top of your FAQs, it’s difficult not to engage with the existential uncertainty it implies. Certainly, some people distrust your answer as soon as you give it, but it is less a matter of someone assuming you are untrustworthy, than someone paternalistically assuming they know who you are better than you know yourself.” You have totally nailed it! Even with almost 50 years on this planet living in this brown skin, people still doubt that I KNOW who and what I am.

@3 PeterErwin

The French Revolutionaries successfully abolished slavery, even if later governments did restore it. They abolished it in every colony that wasn’t held by the Spanish, British, or royalist rebels. And slavery was never restored in Haiti, despite Napoleon’s best efforts.

Notably, the much-praised American Revolution didn’t lead to the abolition of slavery; that happened ninety years later, after a civil war.

The suppression of the Vendee Rebellion is absolutely one of the worst atrocities that the Revolutionary government committed against its own people.

Lots of people are at fault for the French Revolutionary Wars, including the monarchies who decided to invade France to restore the Bourbons. I don’t think the French Revolutionaries carry all of the blame there, and I don’t think it is proper to give them much of the blame for the Napoleonic Wars.

When we discuss revolutions, it is right that we should weigh the costs of a radical approach; the butchery in the Vendee, the savage fratricide as the Revolutionaries struggled for power in Paris, and the brutal suppression of religious and political liberty.

We should also weigh the costs of a moderate approach; ninety years of slavery, followed by a civil war that killed six hundred and twenty thousand Americans. The historians who venerate the Founding Fathers tend to ignore their fondness for leaving problems for other people to deal with; whatever crimes can rightly be laid at the feet of Danton and Robespierre, it should be noted that they actually acted on the statement that “all men are created equal”.

Edit: In hindsight, I do wish that the Temeraire series had featured Temeraire and Laurence going up against the French Revolutionaries rather than Napoleon. It would have created an interesting moral conflict, with Laurence defending the virtues of stability, tradition, and order against a government of bloodthirsty revolutionaries with a tendency to slaughter each other.

But…the crazed revolutionaries are the ones who actually agree with him on the subject of slavery, while his own government has disdain for the cause of abolitionism. It would have been a fun moral conflict.

Napoleon, on the other hand, has basically no redeeming features. He’s competent and intelligent, yes, but he also tries to conquer Europe simply because he wants to, with no regard for the millions of people who die for the sake of his ambition.

Even as a white woman, I have experienced this invisibility, I can only imagine how much more you feel it. Representation matters and Western History has been whitewashed deliberately and skewed towards men.

The first time I read a fictional character that truly resembled me (smart single woman not in the least interested in marriage and children), I was in my 30s. It took my breath away.

I remember reading Hidden Figures a few years ago. I was a space nut in the Sixties (as most of us were) and I was good at math, but what I saw on the TV told me there was no place for women in the space program. I had no idea there were women there or people of color (or like the protagonists, both), they kept them off screen. Only white men need apply to the space program.

Then about two years ago, I saw a marvelous site that had these amazing photos of black people during the Victorian era. And I realized that in my whole life, I had never seen a picture of a black person who wasn’t an entertainer taken before the 1950s and the Civil Rights movement.

People of color or mixed race,women, gays, trans, disabled people, elders have always existed, they have always accomplished things and they have, for much of history, been turned invisible.

We are lucky to live in a time when an author can include those types of characters and not have editors edit them back out or turn them into minor sidekicks.

dptullos @@@@@ 5

Notably, the much-praised American Revolution didn’t lead to the abolition of slavery; that happened ninety years later, after a civil war.

I think the American Revolution is best understood as more a war of independence than a revolution in the classic sense. Fundamentally, the same people were in charge afterwards as were in charge before, just without the British overlordship. (There was a fair amount of quasi-revolutionary rhetoric, which laid the groundwork for future developments.)

(And one should perhaps bear in mind that slavery was legal in all the American colonies on the eve of the Revolution. The first entity to abolish it was Vermont in 1777; by 1804 all the Northern states had done so. So it arguably led to the beginning of abolition in the US; it wasn’t quite a matter of “slavery everywhere for the next ninety years”.)

Lots of people are at fault for the French Revolutionary Wars, including the monarchies who decided to invade France to restore the Bourbons. I don’t think the French Revolutionaries carry all of the blame there, and I don’t think it is proper to give them much of the blame for the Napoleonic Wars.

The French were the ones who declared war on Austria and (unsuccessfully) tried to invade the Austrian Netherlands, which got the whole thing rolling. And I don’t think defending French territory and the preventing the restoration of the Bourbons necessarily justified the enthusiasm with which they annexed territory and set up client states in the Austrian Netherlands, Switzerland, and Italy. (Or the invasion of Egypt.) And there certainly wouldn’t have been Napoleon without the Revolution; he was a consequence of it.

We should also weigh the costs of a moderate approach; ninety years of slavery, followed by a civil war that killed six hundred and twenty thousand Americans.

Or the “moderate approach” of Britain, which yielded a lasting end to slavery in 1833 (1843 in India) without a civil war and without killing hundreds of thousands of their own citizens.

Here’s a story nugget to build on. A society where relationships between men and women of the same ethnic background are outlawed. Roll that forward enough generations when humanity has become so similar, yet the rule hasn’t changed. People have to submit to a colorimter and other tests to determine if they’re different enough.

Even after achieving the goal of making people as identical as possible, they still find differences to cling to.

Sort of a far less silly version of “Let That be Your Last Battlefield”. https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Let_That_Be_Your_Last_Battlefield_(episode)

Nobody brought up Haitia….

Thank you for this post. As another mixed Asian/White person, I never realized how much I appreciated Tharkay until just now. I have many issues with Novik’s handling of non-white people/cultures, but everything you said about Tharkay rings so true for me.

@7: Fundamentally, the same people were in charge afterwards as were in charge before, just without the British overlordship. That’s simplifying; a substantial fraction of the ruling class were loyalists who decamped.

@9: see @5 — or if you don’t mean “Haiti”, please provide explanation. (Haitia is a couple of species of Santo-Domingan plants, says Wikipedia.)

@0: it is regrettable (to put it mildly) that the contributions to the U.S. of people whose ancestry was <100% Western European was not taught even in parts of the country where acknowledging such contributions was not infra dig (or outright upsetting to the power structure); I consider myself lucky just to have learned U.S. colonial history (in the middle 1960’s) from a British woman. Perhaps future generations will get a better picture.

@6: IIRC it has been <10 years since I found out that while we were cheering on “We Seven” there was a short-lived program for female astronauts — a victim of politics and image. (It wasn’t just SF readers who were space nuts; I remember an entire elementary-school class listening to one of the Mercury launches on a transistor radio a student had brought in.) There were independent female protagonists (really independent, not just we’re-done-with-the-revolution-so-I-can-get-married-now) earlier — I read People of the Talisman in 1965 — but they weren’t easy to find; I didn’t find another relevant Ace Double novella, A Planet of Your Own, until the 1980’s (and with assistance), and that paperback series was not particularly visible.

Reading this led to me to recall a (BBC?) documentary about the presence of PoC in London I saw many years ago. I really wish I could remember the name of the documentary or the presenters name, but I do remember he had a phd, and the documentary was based on his work.

Anyhow, he found it remarkable that as a global trade hub London had no PoC through most of its history. As he researched, he found this was of course complete tosh, and since Elizabethan times London has had a steady stream of non-white immigrants, mostly sailors, and many of them (and their offspring) managed to assimilate successfully, and non-white faces would not be a rare sight on a London Street. Part of the problem tracking them though was they adopted (or had forced upon them) Western European names. Ethnicity wasn’t often noted, so if the name sounded English, historians assumed the person was Anglo-Saxon, despite any evidence to the contrary.

Here’s the thing that’s really stuck with me, though. The meaning of “Stranger” has evolved over the centuries, but it used to be interchangeable with “Foreigner” and “Outsider”. His research seemed to suggest if someone was given the surname “Stranger”, it meant the most recognisable thing about them was the colour of their skin marking them out.

He may have been cherry-picking his examples to support his hypothesis, but it seemed pretty compelling.

So he pretty much declared that if you’re family has a English heritage and a surname that can be derived from “Stranger”, you’re likely to have a PoC in your ancestry.

Made me wonder about Dr Strange’s family history, not to mention Clarke’s Jonathan Strange

Still waiting for the Regency (give or take a few years) novel in which the characters travel to Paris and go to a ball where the famous musician perched on a pedestal in the middle of the room is Napoleon’s favorite bandleader…a mixed-race former slave from the Caribbean.

Part of the reason it passed relatively ‘smoothly’ is that Britain paid reparations…to the slave owners, for taking their slaves away from them. It was such a large sum of money that the government loans were only paid off in 2015 (so some of my taxes were used to pay off loans that paid off ex-slave owners, and worse, some of the descendants of former slaves will have also helped pay it off).

When slavery had been abolished in the UK, Britain still profited from buying cotton picked by slaves in the US, and turning it into finished linen. Even during the US Civil War, British businessmen still bought from the Southern states, helping to fund their war.

phuzz @@@@@ 16:

When slavery had been abolished in the UK, Britain still profited from buying cotton picked by slaves in the US, and turning it into finished linen.

Slavery was effectively abolished by court decisions in Britain in the late 18th Century; the 1833 decree abolished it in all British colonies outside India. And of course France and many other countries were buying US cotton as well.

(Also, “linen” is cloth made from the flax plant, not from cotton.)

Even during the US Civil War, British businessmen still bought from the Southern states, helping to fund their war.

The page you linked to actually says

Note the bit about “the Confederacy’s embargo” — the South deliberately restricted its own cotton exports (that is, those exports which might have escaped the imperfect Northern blockade), in hopes of forcing Britain, France, and other European states to recognize and aid them in exchange for restoring the cotton trade. (In practice, yes, there was some trading of smuggled cotton for British weapons via British colonies like Nasaau and Bermuda.)

@17, Yes, the asinine King Cotton ideology. Southerners thought they could the British to recognize them by withholding their cotton. Didn’t work.

Part of the reason it passed relatively ‘smoothly’ is that Britain paid reparations…to the slave owners, for taking their slaves away from them

Which still worked out a lot cheaper than having a civil war. Compensating slave owners cost the British government £20 million – at the time, $100 million. The US civil war cost around $7 billion, and killed six hundred thousand people. If there had been an option (there wasn’t, but if there had been) of paying the cost of one month of the Civil War to the Southern owners of the forced labour camps, and ending slavery, and saving all those lives, and holding the Union together – do you actually think that Lincoln shouldn’t have taken it? I’m pretty sure I know what Lincoln would have said.

Which is the more just outcome depends, I suppose, on your definition of justice – whether it’s the state in which no one receives a benefit they do not deserve, or whether it’s the state in which no one suffers a punishment they have not earned. Is justice about ensuring no criminal walks free, or about ensuring no innocent person is imprisoned? Should it focus on benefit cheats, or on those unable to negotiate the claim process?

Chidi Anagonye would have an answer. At least two, in fact. I don’t – but it’s worth thinking about it in these terms.