Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

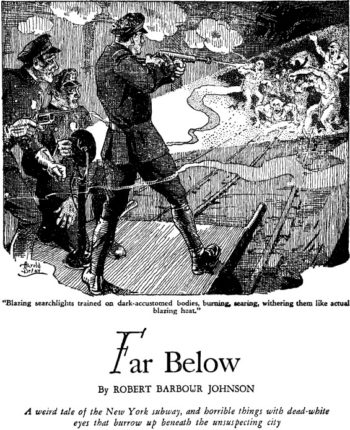

This week, we’re reading Robert Barbour Johnson’s “Far Below,” first published in the June/July 1939 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

With a roar and a howl the thing was upon us, out of total darkness. Involuntarily I drew back as its headlights passed and every object in the little room rattled from the reverberations. Then the power-car was by, and there was only the ‘klackety-klack, klackety-klack’ of wheels and lighted windows flickering past like bits of film on a badly connected projection machine.

Summary

Our narrator visits the workplace of his friend Professor Gordon Craig. It’s Inspector Gordon Craig nowadays—it’s been twenty-five years since Craig left the New York Natural History Museum to head a special police detail stationed in a five-mile stretch of subway. The room’s crowded with switches and coils and curious mechanisms “and, dominating all, that great black board on which a luminous worm seemed to crawl.” The “worm” is Train Three-One, the last to pass through until dawn. Sensors and microphones along the tunnel record its passage—and anything else that might travel through.

The system’s expensive, but no one protested after the subway wreck that occurred just before America entered WWI. Authorities blamed the wreck on German spies. The public would have rioted if they’d known the truth!

In the eerie silence following the train’s roar, Craig goes on. Yes, the public would go mad if they knew what the officers experience. They stay sane by “never quite [defining] the thing in [their] own minds, objectively.” They never refer to the things by name, just as “Them.” Luckily, they don’t venture beyond this five-mile stretch. No one knows why they limit their range. Craig thinks they prefer the tunnel’s exceptional depth.

The subway wreck was no accident, see. They pulled up ties to derail the train, then swarmed on the dead and wounded passengers. Darkness kept survivors from seeing them, though it was bad enough to hear inhuman gibbering and feel claws raking their faces. One poor soul had an arm half-gnawed off, but the doctors amputated while he was unconscious and told him it was mangled by the wreck. First responders found one of them trapped in the wreckage. How it screamed under their lights. The lights themselves killed it, for Craig’s dissection proved its injuries minimal.

The authorities enlisted him as an ape expert. However, the creature was no ape. He officially described it as a “giant carrion-feeding, subterranean mole,” but the “canine and simian development of members” and its “startlingly humanoid cranial development” marked it as something more monstrous still. Only the huge salary made Craig accept a permanent position. That, and the opportunity to study an undocumented creature!

Not entirely undocumented, though, for didn’t the Bible reference “ghouls that burrow in the earth?” Manhattan’s native inhabitants took special precautions to guard their burials. Dutch and English settlers ran night patrols near cemeteries, and dug hasty graves for things unfit to be seen in daylight. Modern writers, too, hint at them. Take Lovecraft—where do you suppose he got “authentic” details?

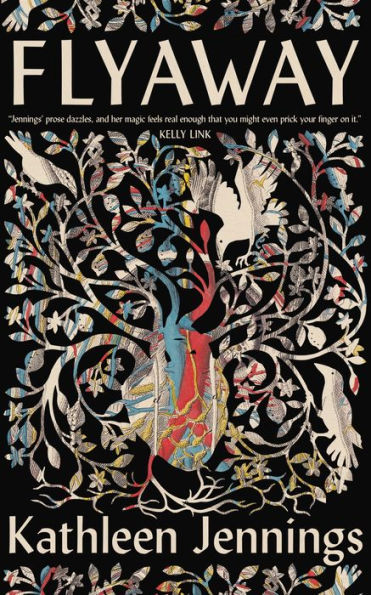

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Craig’s not studied the creatures alive, too. Captives are useful for convincing incredulous authorities to approve the Detail’s work. But Craig can’t keep live specimens for long. They exude an intolerable “cosmic horror” that humans can’t live with in “the same sane world.” Detail officers have gone mad. One escaped into the tunnels, and it took weeks to corner and gun him down, for he was too far gone to save.

On the board a light flickers at 79th Street. A handcar speeds by, carrying armed officers. A radio amplifier emits “a strange high tittering,” growls, moans. It’s their chatter. No worry, the handcar will meet another coming from the opposite direction and trap the creatures between them. Listen, hear their howling, scrabbling flight. They won’t have time to “burrow down into their saving Mother Earth like the vermin they are.” Now they shriek as the officers’ lights sear them! Now machine guns rattle, and the things are dead. Dead! DEAD.

Narrator’s shocked to see how Craig’s eyes blaze, how he crouches with teeth bared. Why hasn’t he noticed before how long his friend’s jaw has become, how flattened his cranium?

Lapsing into despair, Craig drops into a chair. He’s felt the change. It happens to all Detail officers. They start staying underground, shy of daylight. Charnel desires blast their souls. Finally they run mad in the tunnel, to be shot down like dogs.

Even knowing his fate, Craig takes scientific interest in their origin. He believes they began as some anthropoid race older than Piltdown man. Modern humans drove them underground, where they “retrograded” in “the worm-haunted darkness.” Mere contact makes Craig and his men “retrograde” as well.

A train roars by, the Four-Fifteen Express. It’s sunrise on the surface, and people travel again, “unsuspecting of how they were safeguarded… but at what a cost!” For there can be no dawn for the guardians underground. No dawn “for poor lost souls down here in the eternal dark, far, far below.”

What’s Cyclopean: What isn’t cyclopean? The stygian depths of the subway tunnels, beneath the crepuscular earth, are full of fungoid moisture and miasmic darkness and charnel horrors.

The Degenerate Dutch: Native Americans ostensibly sold Manhattan to white people because it was so ghoul-infested. Though they managed to live with the ghouls without exterminating them—it’s only the “civilized” who find them so revolting that they have to carry out “pogroms” with a ruthlessness born of “soul-shuddering detestation.”

Mythos Making: Gordon Craig learned something from Lovecraft—the name Nyarlathotep, if nothing else—and vice versa, though Lovecraft toned it down for the masses.

Libronomicon: You can find ghouls described in the writings of Jan Van der Rhees, Woulter Van Twiller, and Washington Irving, as well as in “The History of the City of New York.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: People would go mad if they knew what was down here in the subway tunnels. And it seems like many who know do go mad. Though given the number of people who know, that might just be probability.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

When I was a kid, I made it to New York once a year, to visit my grandmother in Queens. The rest of the year I lived on Cape Cod, a beautiful seaside community almost entirely free of public transit. I loved—and still love—the subway fiercely, as one would love any magic portal that allows one to travel between destinations simply by stepping through a door and waiting. But I also knew without question that it was otherworldly. The saurian cry of a train coming into the station, the cyberpunk scent of metal and trash wafting from the tracks—I understood well that not everything down there was human or safe, and not every station was on the map.

Lovecraft was famously afraid of the ocean, a medium that humans have plied for millennia even though it can kill us in a moment. But the world beneath the earth’s surface is even less our natural environment, and it’s only in the last century that we’ve traveled there regularly. The New York subway system opened in 1904, a little taste of those mysteries for anyone who used it.

Johnson gives us a mystery—in the old sense, something that people go into a hidden space to experience, and then don’t talk about. Something transformative. But in this case, the transformation and the silence seem less sacred and more a combination of inhumanly horrifying—and humanly horrifying. A gut-churning episode of 99% Invisible talks about how doctors came around to the idea that you should tell people when they had a fatal illness, and how before that they would pretend that the person was going to be fine, and all their relatives had to pretend the same thing, and if the patient figured it out then they had to pretend they believed the lies… speaking of nightmares. If a ghoul had eaten my arm, I’d want to know, and I’d probably want to tell someone.

The (post-war?) cultural agreement to Not Talk About It seems to have gone on for a while, and is certainly reflected in Lovecraft’s desperate-to-talk narrators who, nevertheless, urge the listener to tell no one lest civilization collapse from the correlation of its contents. You can’t tell people bad things, because obviously they can’t handle it. Everyone knows that.

And everyone knows about the ghouls, and no one talks about them. The entire city administration, the relatives who sign off on shooting their transformed family members, doctors who amputate gnawed limbs, all the writers of histories in all the nations of the world… but if they were forced to admit they knew, it would all fall apart.

I spent much of the story wondering whether Johnson was truly conscious of the all-too-human horror in his story. “We filled out full Departmental reports, and got the consent of his relatives, and so on” seems to echo the full-fledged bloodthirsty bureaucracy of Nazi Germany. And “pogroms” isn’t normally a word to be used approvingly. The ending suggests—I hope, I think—that these echoes are deliberate, despite the places where (as the editors say) the story “ages badly.”

I wonder how many readers got it, and how many nodded along as easily as they did to Lovecraft’s entirely un-self-conscious suggestion that there are some things so cosmically horrible that you can’t help attacking them. Even when it’s “no longer warfare.” Even when the Things are howling with terror, shrieking in agony. Some things just need to die, right? Everyone knows that.

And then another awkward question: To what degree is Craig’s xenophobia—his glee at destroying things with “brain convolutions indicating a degree of intelligence that…”—a symptom of his transformation? Which is also to say, to what degree is it conveniently a ghoulish thing, and to what degree is it a human thing? Or more accurately, given how many human cultures have lived alongside (aboveside?) ghouls with far less conflict, to what degree is it a “civilization” thing? For Lovecraftian definitions of civilization, of course.

Anne’s Commentary

Things live underground; we all know this. Fungi, earthworms, grubs, ants, moles, naked mole rats, prairie dogs, trapdoor spiders, fossorial snakes, blind cave fish and bats and star-mimicking glowworms, not to mention all the soil bacteria, though they richly deserve mentioning. It’s cozy underground, away from the vagaries of weather. Plus it’s a good strategy for avoiding surface predators, including we humans. The strategy’s not foolproof. Humans may not have strong claws for digging, but they can invent stuff like shovels and backhoes and, wait for it, subways!

Subways, like cellars and mines and sewers, are human-made caves. Some are cozy, say your finished basements. Others, like their natural counterparts, are inherently scary. They’re dark, and claustrophobic, and (see above) things live in them. Pale things. Blind things. Squirmy, slimy things. Disease-carrying things. Things that might like to eat us. Things that inevitably will eat us, if we’re buried underground after death.

It’s no wonder ghouls are among the most enduring monsters in our imaginations. Robert Barbour Johnson’s are quintessential ghouls, closely akin to Lovecraft’s Bostonian underdwellers, on whom they’re based. One of Pickman’s most terrifying paintings is his “Subway Accident,” in which he imagines ghouls rampaging among the commuters on a boarding platform. Or did Pickman only imagine it? Could Boston have suffered a calamity like the one in Johnson’s New York—and one as successfully covered up? If so, Pickman would have known about it, for his ghoul friends would have bragged about the incident.

Johnson’s father worked as an undercover railroad policeman, family background that made Johnson a natural to write “Far Below.” It’s the most famous of the six pieces he published in Weird Tales; in 1953, readers voted it the best of the magazine’s stories, ever. That’s saying a hell of a lot for its popularity, considering it beat the likes of Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, C. L. Moore, Robert Bloch and, of course, our Howard himself. Lovecraft admired Johnson’s work. In “Far Below,” Johnson returned the compliment by name-checking Lovecraft in the time-honored manner of claiming him as a scholar of factual horrors, thinly disguised as fiction.

Johnson’s tribute to “Pickman’s Model” extends to the form of “Far Below” in that it’s largely an account given by a ghoul-traumatized man to a friend. It adds more present-moment action in that the listening friend personally witnesses ghoul activity and then realizes his friend is himself “retrograding” to ghoulishness. It adds horror for narrator and reader in that narrator can’t write off Craig as delusional. It adds terror in that if Craig is “ghoulizing” by spiritual contagion from them, might not narrator catch at least a mild case of “ghoul” from Craig?

Craig may delude himself by theorizing ghouls originated in a “lesser” ancestor of mankind—Homo sapiens, such as himself, are obviously not immune to the “retrograde” tendency. Irony compounds because Homo sapiens may have created ghouls by driving their progenitor species underground. H.G. Wells dished up similar irony in The Time Machine, imagining future humans who’ve differentiated into two races. Elites drove underclass workers actually underground, where they “devolved” into the cannibalistic (ghoul-like) Morlocks who prey on the privilege-weakened elite or Eloi. I also recall the 1984 movie C.H.U.D., which stands for Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers. See, the homeless were driven into the sewers, where they encountered hazardous chemical waste cached in the tunnels. The homeless people mutated into (ghoul-like) monsters who emerged to eat their former species-mates, that is, us. Our fault, for (1) allowing homelessness, and (2) countenancing illegal dumping.

Lovecraft, on the other hand, doesn’t blame humanity for the ghouls. In the Dreamlands, they’re just part of the weird ecosystem. In the waking world, ghouls and humanity are clearly related species, with intermixing a possibility. “Pickman’s Model” narrator Thurber has an affinity for the macabre strong enough to have drawn him to Pickman’s art but too weak to embrace the reality of the nightside—he’s vehemently anti-ghoul. Johnson’s internal narrator Craig is more complex. At first he presents as gung-ho anti-ghoul, a proper bulwark between bad them and good us. As the story advances, he subtly evinces sympathy for the ghouls. The Inspector protests too much, I think, in describing how devilish they are, what spawn of hell! When relating the capture and killing of ghouls, he dwells on their agonies with surface relish and underlying empathy, and why not? Due to the spiritual “taint” that increasingly ties Craig to them, are not the ghouls more and more his kin? In his theory of their origin, does he not portray them as the victims of fire and steel, pogrom and genocide?

Poor Craig, his acceptance of impending ghoulhood is tortured. He’ll go into the tunnels only to be gunned down. What a contrast to Lovecraft’s Pickman, who seems to anticipate his transformation with glee. What a contrast to Lovecraft’s Innsmouth narrator, who anticipates outright glory in metamorphosis.

I guess it makes sense. Most of us would have reservations about living in subway tunnels, especially the dankest, darkest, deepest ones. Whereas Y’ha-nthlei far below sounds like an undersea resort of the highest quality.

Can I make a reservation for the Big Y, please? Not that I wouldn’t visit the tunnels with the ghouls, provided you could get rid of those pesky humans with overpowered flashlights and machine guns.

Next week, we go back about ground but still hide from the light with Autumn Christian’s “Shadow Machine.” You can find it in Ashes and Entropy.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

“…didn’t the Bible reference “ghouls that burrow in the earth?”

Did it? I mean, there’s all sorts of critters in the bible, often with more heads than seem strictly reasonable, and some of which are dubiously either vampires or owls, but I’d never heard of ghouls being among them, and a quick google mostly only turns up the text of this story. Perhaps, being an academic in a Lovecraft story, Craig has access to some unorthodox translations.

Maybe it’s the effect of too much D&D, but when you tell me there’s a possibility of turning into some not-quite-human creature, my instinct is to start drawing up a pros and cons list. Darkvision (or, dare I hope, blindsight?) is always handy, and Lovecraft ghouls seem likely to come with some nasty natural attacks, but do I get immunity to aging penalties like the Deep Ones seem to?

I do not believe there are any ghouls mentioned in the Bible. Ghosts? Yes.

Maybe it’s the effect of too much D&D, but when you tell me there’s a possibility of turning into some not-quite-human creature, my instinct is to start drawing up a pros and cons list.

The D&D game I’m playing in right now has four PCs, all of whom are part-human. Three of us do indeed have darkvision.

@3: You always (or at least, I always) feel bad for the one character NOT to have darkvision, especially if they’re not magic themselves and have to bother one of their party members for a light.

I’m enjoying the discussion, but one thing confuses me. Is there a particular “girl” perspective or viewpoint being expressed, or is it just two skilled and knowledgeable genre writers?

If the latter, is the tag line “in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox” something more than signaling?

Because I have rather strong opinions about this story, I’m going to post this reply before reading what Anne and Ruthanna have to say, because I don’t want my thoughts coloured by their comments. So if I repeat anything that they said, my apologies in advance.

To some extent “Far Below” reminds me of Paul Ernest’s “The Microscopic Giants”, which is about the deepest copper mine in the world, where, in the middle of the (then future) World War Of 1941, the protagonist and his assistant find miniature humanoids who live at mind boggling depths underground. Said humanoids are incredibly dense, so much so that they can walk through soft rock and concrete, and so advanced scientifically that their weapons totally outclass those of surface people.

Having lost his assistant and one of his hands trying to fight the denizens of the deeps, the protagonist dynamites the mine in order to prevent the two species coming into contact. Even though there’s a war raging, nobody on top questions his decision, partly because the mine was so deep it wasn’t economical anyway.

In “Down Below”, however, the so-called protagonist and the other humans are definitely not willing to let the creatures under the ground – whatever they may be – alone. What these creatures are I’m not too sure; weremoles that eat the dead aren’t apparently the same as the friendly, valorous meeping ghouls of “The Dream Quest Of Unknown Kadath”. I’m in fact reminded of the werewolves of the Canadian “Ginger Snaps” film trilogy, where werewolves don’t change from humans at the full moon and back again; once you’re bitten you suffer a slow, irreversible metamorphosis into a bloodthirsty monster and there is no going back, not even for the titular Ginger and her sister Brigitte. Exactly the same way, apparently, in this story you become a weremole monster, just by sharing the monsters’ environment (which you humans have invaded) too long.

This is important for reasons I’m going to mention in a minute.

For the next part of my comment I will have to speculate that the author did not consciously think of the message he was actually pushing. I will have to look at his era and the way the story is written and assume that for his intended audience the human “protagonist” was the hero and the weremole monsters evil villains requiring extermination.

This does not gel well with most modern sensibilities. Normal modern people recoil at the idea of genocidal extermination of something we merely do not understand. But I’m as certain as I can be that this was not the case in the 1930s. The author intended the audience to cheer the humans who murdered the weremole monsters even after they were caged and helpless.

Now, I’m not personally familiar with the history of American imperialism. I am extremely familiar with the history of British imperialism. But I have read, for instance, “Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee”, and from what I can see the basic difference between American and British imperialism is that while the Brits used to enslave and exploit their subject people, American imperialism was based more on extermination to make room for the imperial conquerors. The Brits would have used the weremole monsters to, for instance, dig up mineral ores or construct tunnels for the underground trains. The American protagonists can think of nothing better than wholesale extermination.

But that’s not the only thing. When I read the story my first response was “this is a colonial tale!” And that’s because there is one thing I thought of immediately, that is British imperalist to the core. Possibly it’s American imperalist as well, I can’t tell.

It’s this: when the Brits ruled India for 190 years, they had hatred and contempt for us Indians enough. But they had even more hatred and contempt for those British, and there were not a few, who chose to “go native” – who adopted Indian dress and customs, married Indian women, turned their back on the “mother country”, and implicitly rejected the whole notion of the Superior Race. The Brits were so terrified of this that they imported their own clubs, their polo games, even their bewigged judges and courtroom practices, to their Indian colonies. They didn’t have to be bitten by a radioactive Indian to “go native”; the environment was enough to do the damage, apparently.

Exactly the same way, the subway environment was apparently enough to convert the “valiant” protagonist and his cohorts, over time, into weremole monsters. That’s why they hate the original weremoles so much: it’s because of the fear of contamination just by living in the same space.

You’d wonder if they ever questioned to themselves whether their cherished imperalism was worth it.

By the way, I’ve found a site called the Lovecraft ezine that posted regular issues of neo Lovecraftian fiction for several years – a total of 37 issues – and an reading my way through it. The quality is uneven but some stories are quite good. Maybe some of you would like a look.

I’ll read the reread now.

@6- American imperialist attitude towards native peoples is heavily shot through with Noble Savage bullshit, so I would expect a story directly reflective of that to take a moment to mourn the loss of the ghouls ‘finer, freer way of life’- while still appreciating, of course, that they’ve been wiped out and are no longer in the way of progress.

To be fair, the humans became aware of the ghouls when the ghouls deliberately trapped and murdered what may have been several hundred humans. And they were eating them alive.

But, I see the story strongly hinting that the ghouls are human, full stop. Maybe some of them have the equivalent of a little ghoul-house with a little ghoul-spouse and 2.5 little ghoul-kiddies, but I get the feeling that most of them are humans who’ve been down in the darkness too long. They’ve changed but what they’ve changed into is monstrous because it’s human, not because it isn’t.

Part of Craig’s monstrousness is that he’s still sacrificing people to destroy the ghouls, even though he admits this is creating more ghouls. The implied solution–live in the sunlit world and avoid the dark tunnels–never even gets a mention.

Er, side issue. I understand the development of a subway system had been put off in New York for ages by Tammany Hall corruption until the blizzard of 1888 and it’s resulting death toll made the need for a reliable transportation system that people wouldn’t freeze to death while waiting for clear. So, maybe scrapping the subway system wouldn’t work or wouldn’t work without an alternative in place. But, there are cities that manage without one.

Also, the story was made into an episode of the TV show Monsters, although I think they left out the part about humans becoming the monsters.

That opening is terrific. Much of the structure of the rest of the story is less successful. This sort of second-hand narrative was quite common in the pulp days. “One is dead, one is mad, and only I survive to tell the tale,” was quite the trope. It could be done well — “Pickman’s Model” is a good example — but for me this one is a little subpar. The middle third or so sagged, before picking up again as Craig becomes overly excited.

The story also intersects very.. badly? Oddly? Let’s go with oddly. It intersects oddly with current events. Johnson undoubtedly meant us to sympathize with the goals of Craig’s unit and to pity Craig’s eventual fate. But as others have noted, by today’s standards it’s easy to read through a lens of colonial imperialism or perhaps racism.Craig’s bloodlust really set me on edge, and while the authorial intent was most likely “becoming the thing he’s fighting against” or “going native”, you have to wonder how much of the interpretation of the ghouls reflects the reality of the situation.

This story, about the ‘guardians of public order’ turning into monsters, is extremely topical these days. Ruthanna and Anne, was this just coincidence or did the coverage of the crackdown on protesters inspire it?

I am commenting with my phone now, I will put up a more substantial comment later, when I have more free time.

Did the author know that Piltdown man was a fake?

@11: The Piltdown Man wasn’t shown to be a fake until the 1950s.

@11 My (certainly imperfect!) understanding is that while there were questions about the provenance of Piltdown man pretty much from day one, it wasn’t conclusively exposed as a forgery until the fifties.

bengi and Benjamin are correct about Piltdown man. I even have a book written by a respected anthropologist written in 1952 which treats Piltdown man as authentic.

Kirth @@@@@10: We picked out the story three weeks ago and wrote the commentaries two weeks ago–my commentary was certainly shaped by current events, as well as my difficulty sympathizing with any character speaking approvingly of pogroms even when that character isn’t a cop advocating genocide. I’m not at all sure what the authorial intent was meant to be–it’s certainly more ambiguous than “Shadow Over Innsmouth.” I could probably get a whole separate essay out of comparing the two, another week.

Everyone’s alternate analyses are thought-provoking, especially the points about “going native” as a trope. Biswapriya @@@@@ 6 talks about this as a facet of British imperialism; it’s less common in American imperialism primarily because of a reluctance to admit that it happens (and more recently a profound tendency to cut the process off by commodifying it). But for some time after first contact between Europe and the Americas, there was quite a lot of European concern about colonists (especially women) leaving their colonies to integrate with Native American communities–and a separate concern about enslaved people escaping to do the same. (Much of what I know about this history comes from Mann’s 1491, which I highly recommend.)

Speaking of paragraphs that could be whole separate essays.

“When an Indian child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and makes one Indian ramble with them, there is no persuading him ever to return. [But] when white persons of either sex have been taken prisoners young by the Indians, and lived a while among them, tho’ ransomed by their friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay among the English, yet in a short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first good opportunity of escaping again into the woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.”

I’ve seen that attributed to Ben Franklin a couple places, although I can’t place it’s origin with any real confidence. And I suppose it’s interesting that stories of ghouls or Deep Ones raised or imprisoned on the surface tend to end with their return to the tunnels or the oceans, respectively, whereas one rarely sees Craig or his fellows returning to human life after a sojourn among the ghouls.

@15. Thanks, Ruthanna! I suspect that you and Anne received a premonition from the Dreamlands, or maybe from gazing into the Shining Trapezohedron…

I unabashedly love both the NYC transit system and stories about ghouls, morlocks, CHUDs, or Deros, so this one has been a favorite since I read it. The good people at the SFF Audio Podcast did an audiobook ‘readalong’ of the story a few years back. The ‘Monsters’ episode can be found online, and it changes some details, but the whole ‘we have met the monsters and they are us’ theme is intact. Reading the story, I kept thinking of how many times I’ve ridden both the Lexington Avenue and 7th Avenue lines between the Bronx and Manhattan, and I could see that big board in my mind.

The system’s expensive, but no one protested after the subway wreck that occurred just before America entered WWI. Authorities blamed the wreck on German spies. The public would have rioted if they’d known the truth!

This detail is loosely based on a real occurrence, a 1918 subway crash that was so horrific, the city changed the name of the street near which it happened.

@16: Paulette Jiles’s historical fiction novel News of the World deals with this a bit. The main character is bringing a girl who was kidnapped by a Native American tribe (I think the Apache?) to her aunt and uncle. Thing is, she was kidnapped very young and has no memory of her now-deceased parents, let alone the aunt and uncle. She speaks very little English and is uncomfortable with the customs of white society. She does build up a bond of trust with the main character, but he gradually starts questioning whether returning her to her birth family is actually the right thing to do.

There’s a similar episode of Star Trek: TNG, too, with a boy who was raised by an alien species that used to be at war with the Federation after the death of his parents in one of the battles. His human grandparents want him back, but he has no knowledge of human/Federation culture and doesn’t see his biological grandparents as his family.

You really could write a whole essay about that particular plot trope.

@6

Unfortunately the experience of indigenous Australians at the hands of the British colonialists was one of massacre and genocide. In that context the protagonists of “Far Below” fit a “modern” trope of generic imperialists exterminating the indigenous inhabitants of the land they seek to conquer and exploit.

@1. Maybe it’s the effect of too much D&D, but when you tell me there’s a possibility of turning into some not-quite-human creature, my instinct is to start drawing up a pros and cons list.

NARRATOR: There’s no such thing as too much D&D.

Now roll for initiative!!!!

Now I haven’t read The Shadow Over Innsmouth in a while but as I recall the young and cheerful shopkeeper the narrator meets was not from Innsmouth but was left unmolested by the Deep One residents of the town. If the narrator had not been, albeit unknown to himself, a Deep One, I don’t think they would have come for him in his hotel room. That’s the basic difference between it and Far Below, which I miscalled “Down Below” for some doubtless Freudian reason in my earlier comment. The “protagonists” of the latter tale don’t have to be part weremole monster, all they have to do is invade the realms of the weremole monsters. There’s a lot of fiction inspired by Lovecraft’s tale including no less than three compilations on the theme of Weird Shadows Over Innsmouth, and one not too bad film, which for some reason is called Dagon. It would be interesting to see if anyone came up with a story, even one, from the point of view of the weremole monsters. I don’t recall reading any story from the point of view of the Lovecraftian ghouls either, though they were treated very sympathetically in my personal favourite original Lovecraft piece of writing, The Dream Quest Of Unknown Kadath.

I came across this story in an anthology a few years ago and did a little reading about. I think I remember reading that the point was that what Craig is doing is monstrous and would have been monstrous to readers back in the day, but I can’t find it. So, I don’t know if I’m remembering wrongly or if I read someone giving a modern reader’s take or if it’s just some deep rooted need to cast a cloying pall of niceness over things.

Do wonder what happens if Pollyanna ever wanders into Lovecraft fiction. I suppose she’d say that, no matter what happens, “It’s a Good Life.” Maybe she and Anthony had more in common than I thought.

@21 Whited out spoiler text for a ninety-year old story.

I don’t think the narrator of The Outsider is ever specifically identified as a ghoul, though he does describe his appearance as ghoulish, but he’s something, and the story ends with him running off to live with the ghouls.

Love is Forbidden, We Croak and Howl, is a love story between a ghoul and a Deep One.

Biswapriya @@@@@ 21:

One of Jonathan Howard’s Johannes Cabal novels, Johannes Cabal: The Fear Institute, takes place mostly in the HPL Dreamlands, and has a great deal of involvement with ghouls. To say too much more would spoil things.

Me @@@@@ 24:

By the way, since I’m speaking of Jonathan Howard, one of the eponymous stars of his other series Carter & Lovecraft is HPL’s (fictional) only descendant, a black woman who owns a rare book store. I’m 100% sure he wrote her character particularly because of how mad it would have made HPL. (The other character is a PI descended from Randolph Carter.)

Very enjoyable noir-ish eldritch action with plenty of twists and takes on the mythos background and some great lines like “Of course I can handle a gun; I trained as a librarian.” There are two books in the series so far, but unfortunately it hasn’t sold well enough as yet for the publisher to commit to a third. Everyone should buy them so that the publisher agrees to publish a third!

I’m rather fond of the Boston subway (and bus and train) system that made it possible for me to intern at the New England Aquarium even though I can’t drive, and have missed it ever since. But I’m glad it never got attacked by ghouls (or mundanely crashed, for that matter) while I was on it.

I’ve only visited caves twice and only remember one such visit, a boat ride in Lost River Cave in Kentucky, which I loved and praised at length in the comments on The Beast in the Cave. But I’m very partial to the natural and fictional inhabitants of caves and soil-burrows. Incidentally, I recently heard about the not-so-recent discovery of an extraordinary chemosynthesis-based food web in a cave believed to have been sealed for millions of years.

“See, the homeless were driven into the sewers,where they encountered hazardous chemical waste cached in the tunnels.” Urrrrgh, that makes me picture the PowerPuff Girls episode where a hamster flushed down a toilet falls into a sewage-carried can of radioactive something and instantly mutates into a giant monstrous hamster.

@16 and @18

The Searchers, a John Ford/John Wayne western, is all about men dealing (very badly) with a woman “going native.”